Of the EEC Treaty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spaak Committee

The Spaak Committee Source: CVCE. European NAvigator. Étienne Deschamps. Copyright: (c) CVCE.EU by UNI.LU All rights of reproduction, of public communication, of adaptation, of distribution or of dissemination via Internet, internal network or any other means are strictly reserved in all countries. Consult the legal notice and the terms and conditions of use regarding this site. URL: http://www.cvce.eu/obj/the_spaak_committee-en-2c330a16-0797-4e30-9a6b- d3c6de5ada0e.html Last updated: 08/07/2016 1/2 The Spaak Committee From 9 July 1955 to 21 April 1956, a working party, composed of delegates from the six governments and chaired by the Belgian Minister for Foreign Affairs, Paul-Henri Spaak, undertook the task of drawing up a report which would sketch the broad outline of a future European Economic Community (EEC) and a European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC). In October 1955, although it had participated in the first preparatory sessions, the United Kingdom decided to play no further part in the work of the Spaak Committee, whose chances of success it saw as slight and, at all events, not altogether desirable. The British opposed a customs union because they wanted to maintain their autonomy with regard to the setting of tariffs, protect their industries and maintain the privileged links that they enjoyed with their Commonwealth partners. Besides, Britain, which had had the atomic bomb since 1952 and was already financing nuclear research programmes with the United States and Canada, did not want to compromise that fruitful collaboration by associating itself with Euratom. The working party, whose meetings were also attended initially by representatives of the High Authority of the ECSC, drew up a Report of the Heads of Delegation to the Foreign Ministers, which served as the basis for negotiations during the conference of the six Ministers for Foreign Affairs, which was held in Venice on 29 and 30 May 1956. -

The Bank of the European Union (Sabine Tissot) the Authors Do Not Accept Responsibility for the 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 Translations

The book is published and printed in Luxembourg by 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 15, rue du Commerce – L-1351 Luxembourg 3 (+352) 48 00 22 -1 5 (+352) 49 59 63 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 U [email protected] – www.ic.lu The history of the European Investment Bank cannot would thus mobilise capital to promote the cohesion be dissociated from that of the European project of the European area and modernise the economy. 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 The EIB yesterday and today itself or from the stages in its implementation. First These initial objectives have not been abandoned. (cover photographs) broached during the inter-war period, the idea of an 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 The Bank’s history symbolised by its institution for the financing of major infrastructure in However, today’s EIB is very different from that which 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 successive headquarters’ buildings: Europe resurfaced in 1949 at the time of reconstruction started operating in 1958. The Europe of Six has Mont des Arts in Brussels, and the Marshall Plan, when Maurice Petsche proposed become that of Twenty-Seven; the individual national 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 Place de Metz and Boulevard Konrad Adenauer the creation of a European investment bank to the economies have given way to the ‘single market’; there (West and East Buildings) in Luxembourg. Organisation for European Economic Cooperation. has been continuous technological progress, whether 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 • 1958-2008 in industry or financial services; and the concerns of The creation of the Bank was finalised during the European citizens have changed. -

Download PDF (422.4

Table of cases and legislation EUROPEAN UNION Communications, Guidance and Notices Communication from the Commission, Guidelines on the application of Art. 81(3) of the Treaty, 2004/C 101/08, OJ C101/97, 27.4.2004 ............................270 Guidance on the Commission’s enforcement priorities in applying Art. 82 of the EC Treaty to abusive exclusionary conduct by dominant undertakings, OJ C045, 24.02.2009 ......................................................................................269 Commission Notice ‘Guidelines on Vertical Restraints,’ European Commission, Brussels, 10 May 2010, SEC (2010) ................................. 272, 273 Communication from the Commission, Guidelines on the Applicability of Art. 101 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union to Horizontal Co-operation Agreements, OJ, 2011/C 11/01, 2011 ......................270 Decisions Commission Decision (86/398/EEC) relating to a proceeding under Art. 85 of the EEC Treaty (IV/31.149 – Polypropylene), [1986] OJ L230/1, [1988] 4 CMLR 347 .................................................................................................266 Regulations Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 of 16 December 2002, OJ L 1, 4.1.2003 Art. 2 .............................................................................................................174 Art. 9 .............................................................................................................267 Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 on the control of concentrations between undertakings, OJ -

The Conference on the Future of Europe a New Model to Reform the EU?

The Conference on the Future of Europe A New Model to Reform the EU? Federico Fabbrini* WORKING PAPER No 12 / 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Plans for the Conference on the Future of Europe 3. Precedents of the Conference on the Future of Europe 4. The rules on EU treaty reform 5. The practice of inter-se treaties outside the EU legal order 6. Reforming the EU through a Political Compact 7. Conclusions ABSTRACT The paper offers a first analysis of the recent plan to establish a Conference on the Future of Europe to reform the European Union (EU), comparing this initiative with two historical precedents to relaunch the EU – namely the Conference of Messina and the Convention on the Future of Europe – and considering the legal rules and political options for treaty reform in the contemporary EU. To this end, the paper overviews prior efforts to reform the EU, and points out the conditions that led to the success or failures of these initiatives. Subsequently it examines the technicalities of the EU treaty amendment rules and emphasizes the challenge towards treaty reform resulting from the need to obtain unanimous approval by all member states. The paper then assesses the increasing tendency by member states to use inter-se international treaties – particularly in response to the euro-crisis – and underlines how these have introduce new ratification rules, overcoming unanimity. Drawing lessons from these precedents, finally, the paper suggests what will be a condition for the success of the Conference on the Future of Europe, and argues that this should resolve to draft a new treaty – a Political Compact – designed to push forward integration among those member states that so wish. -

Steps to European Unity Community Progress to Date: a Chronology This Publication Also Appears in the Following Languages

Steps to European unity Community progress to date: a chronology This publication also appears in the following languages: ES ISBN 92-825-7342-7 Etapas de Europa DA ISBN 92-825-7343-5 Europa undervejs DE ISBN 92-825-7344-3 Etappen nach Europa GR ISBN 92-825-7345-1 . '1;1 :rtOQEta P'J~ EiiQW:rtTJ~ FR ISBN 92-825-7347-8 Etapes europeennes IT ISBN 92-825-7348-6 Destinazione Europa NL ISBN 92-825-7349-4 Europa stap voor stap PT ISBN 92-825-7350-8 A Europa passo a passo Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 1987 ISBN 92-825-7346-X Catalogue number: CB-48-87-606-EN-C Reproduction authorized in whole or in pan, provided the source is acknowledged Printed in the FR of Germany Contents 7 Introduction 9 First hopes, first failures (1950-1954) 15 Birth of the Common Market (1955-1962) 25 Two steps forward, one step back (1963-1965) 31 A compromise settlement and new beginnings (1966-1968) 35 Consolidation (1968-1970) 41 Enlargement and monetary problems (1970-1973) 47 The energy crisis and the beginning of the economic crisis (1973-1974) 53 Further enlargement and direct elections (1975-1979) 67 A Community of Ten (1981) 83 A Community of Twelve (1986) Annexes 87 Main agreements between the European Community and the rest of the world 90 Index of main developments 92 Key dates 93 Further reading Introduction Every day the European Community organizes meetings of parliamentar ians, ambassadors, industrialists, workers, managers, ministers, consumers, people from all walks of life, working for a common response to problems that for a long time now have transcended national frontiers. -

Representations of Social Europe

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Toulouse Capitole Publications Representations of Social Europe Arnaud Lechevalier (Université Paris 1 ; LISE, UMR CNAM-CNRS 3320 ; Centre Marc Bloch, UMIFRE N°14 CNRS-MAE, Humboldt University of Berlin), Fransesco Laruffa (Graduate School of Social Science, Humboldt University of Berlin), Maryse Salles (University of Toulouse), Gabriel Colletis (University of Toulouse). Communication au Colloque « Les usages de la sociologie des politiques sociales », organisé les jeudi 2 et vendredi 3 octobre 2014 par le Centre Georges Chevrier (Université de Bourgogne – CNRS) et le réseau RT6 de l’AFS à la Maison des Sciences de l’Homme de Dijon. Abstract: Two main political and economic paradigms have framed the Social Europe so far. The first one has consisted in the (German) “ordoliberalism”, which has played a key role in structuring the foundations of the European Community as well as those of the Monetary Union. The other and more recent one is the so called “Social Investment Strategy” ” recently endorsed by the European Commission. Both normative frameworks have been also at the heart of the responses formulated at the European level to the euro crisis. Therefore, they have had decisive consequences on the current social situation in the Economic and Monetary Union. This paper uses a theoretical and methodological framework, that combine Weltanschauungen (or doxai), principles and norms, for analyzing models of representations of social facts. This grid of analysis is used to understand what has happened to the Social Europe in the wake of the current Eurozone crisis and to formulate some alternatives. -

60 Years Ago: the Foundation of EEC and EAEC As Crisis Management

9 60 Years ago: The Foundation of EEC and EAEC as Crisis Management Wilfried LOTH With the failure of the EDC in August of 1954, the project of a political Europe receded into the distance for the time being. Essential security functions were now to be carried out by NATO. In an upsurge of emotion, a group decisive for making a majority in France had turned against the supranational principle; and in the remaining countries of the Community of the Six, the French rejection had had a demoralizing effect. Yet, the problem clearly still remained of the independence of the Europeans vis-à-vis the US as the leading power, though under the changed circumstances of inclusion in the nuclear security community. Also, the problem of incorporating the Germans, which was ever more clearly a problem of incorporating German economic strength, had not yet been satisfactorily resolved. The problem of economic unifica- tion became more urgent, not only because the sectoral integration of coal and steel was oriented toward expansion but also because there was a growing number of firms and branches urging the elimination of hindrances to trade. In this situation, what mattered more than ever was skillful crisis management: Only if the remaining in- terests in unification were successfully bundled was there a prospect of overcoming the hurdles stemming from the consolidation of nation-state structures that had in the meantime been achieved.1 The Difficult “Relance” In the search for unification projects that could be implemented without major res- istance and were therefore suitable for overcoming the paralysis of the integration process resulting from the EDC shock, the High Authority of the ECSC firstly aimed for the extension of the union to other energy branches and to transport policy. -

The Founding Fathers of the EU the European Union Explained

THE EUROPEAN UNION EXPLAINED The founding fathers of the EU THE EUROPEAN UNION EXPLAINED This publication is a part of a series that explains what the EU does in different policy areas, why the EU is involved and what the results are. You can see online which ones are available and download them at: http://europa.eu/pol/index_en.htm How the EU works Europe 2020: Europe’s growth strategy The founding fathers of the EU Agriculture Borders and security Budget Climate action Competition Consumers Culture and audiovisual The European Union explained: Customs The founding fathers of the EU Development and cooperation Digital agenda European Commission Economic and monetary union and the euro Directorate-General for Communication Education, training, youth and sport Publications Employment and social affairs 1049 Brussels Energy BELGIUM Enlargement Enterprise Manuscript completed in May 2012 Environment Fight against fraud Photos on cover and page 2: © EU 2013- Corbis Fisheries and maritime affairs Food safety 2013 — pp. 28 — 21 x 29.7 cm Foreign affairs and and security policy ISBN 978-92-79-28695-7 Humanitarian aid doi:10.2775/98747 Internal market Justice, citizenship, fundamental rights Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, Migration and asylum 2013 Public health Regional policy © European Union, 2013 Research and innovation Reproduction is authorised. For any use or reproduction Taxation of individual photos, permission must be sought directly Trade from the copyright holders. Transport THE founding fathers OF THE EU The founding fathers of the EU Over half a century ago a number of visionary fathers were a diverse group of people who held leaders inspired the creation of the European the same ideals: a peaceful, united and Union we live in today. -

Europe's Troubles Sebastian Rosato

Europe’s Troubles Europe’s Troubles Sebastian Rosato Power Politics and the State of the European Project For a decade after the end of the Cold War, observers were profoundly optimistic about the state of the European Community (EC).1 Most endorsed Andrew Moravcsik’s claim that the establishment of the single market and currency marked the EC as “the most ambitious and most successful example of peaceful international co- operation in world history.” Both arrangements, which went into effect in the 1990s, were widely regarded as the “ªnishing touches on the construction of a European economic zone.”2 Indeed, many people thought that economic inte- gration would soon lead to political and military integration. Germany’s min- ister for Europe, Günter Verheugen, declared, “[N]ormally a single currency is the ªnal step in a process of political integration. This time the single currency isn’t the ªnal step but the beginning.”3 Meanwhile, U.S. defense planners feared that the Europeans might create “a separate ‘EU’ army.”4 In short, the common view was that the EC had been a great success and had a bright future. Today pessimism reigns. When it comes to the economic community, most analysts agree with former German Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer’s claim that it is “in a moment of a very severe crisis.” The conventional wisdom, notes the European Union’s ambassador to the United States, João Vale de Almeida, is that the EC “is dying, if not already dead.”5 At the same time, hardly anyone still predicts political or military integration. -

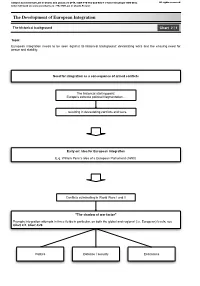

The Development of European Integration

Sample: Essential EU Law in Charts 2nd Lisbon ed 2010, ISBN 978-963-258-086-9 ©Tobler Beglinger HVG-Orac All rights reserved. Order full book on www.eur-charts.eu - The EU Law in Charts Project The Development of European Integration The historical background Chart 2 | 1 Topic: European integration needs to be seen against its historical background: devastating wars and the ensuing need for peace and stability. Need for integration as a consequence of armed conflicts The historical starting point: Europe's extreme political fragmentation... ... resulting in devastating conflicts and wars. Early on: idea for European integration E.g. William Penn's idea of a European Parliament (1693). Conflicts culminating in World Wars I and II "The shadow of war factor" Prompts integration attempts in three fields in particular, on both the global and regional (i.e. European) levels; see Chart 2/2, Chart 2/28. Politics Defence / security Economics Sample: Essential EU Law in Charts 2nd Lisbon ed 2010, ISBN 978-963-258-086-9 ©Tobler Beglinger HVG-Orac All rights reserved. Order full book on www.eur-charts.eu - The EU Law in Charts Project The Development of European Integration International cooperation and plans for European integration Chart 2 | 2 Topic: After World War II, tangible cooperation happened first on the global level. While suggestions and plans were also made on the European level, what was in mind here was more than mere cooperation. International cooperation on the global level Various international organisations and fora for international cooperation in different fields, including in particular: Politics Defence / security Economics 1945: United Nations (UN). -

Wilfried Loth Building Europe

Wilfried Loth Building Europe Wilfried Loth Building Europe A History of European Unification Translated by Robert F. Hogg An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. ISBN 978-3-11-042777-6 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-042481-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-042488-1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2015 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover image rights: ©UE/Christian Lambiotte Typesetting: Michael Peschke, Berlin Printing: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Table of Contents Abbreviations vii Prologue: Churchill’s Congress 1 Four Driving Forces 1 The Struggle for the Congress 8 Negotiations and Decisions 13 A Milestone 18 1 Foundation Years, 1948–1957 20 The Struggle over the Council of Europe 20 The Emergence of the Coal and Steel Community -

Paul–Henri Spaak: a European Visionary and Talented Persuader

Paul–Henri Spaak: a European visionary and talented persuader ‘A European statesman’ – Belgian Paul-Henri Spaak’s long political career fully merits this title. Lying about his age, he was accepted into the Belgian Army during the First World War, and consequently spent two years as a German prisoner of war. During the Second World War, now as foreign minister, he attempted in vain to preserve Belgium’s neutrality. Together with the government he went into exile, first to Paris, and later to London. After the liberation of Belgium, Spaak served both as Foreign Minister and as Prime Minister. Even during the Second World War, he had formulated plans for a © Nationaal Archief/Spaarnestad Photo Archief/Spaarnestad © Nationaal merger of the Benelux countries, and directly after the war he campaigned for the Paul-Henri Spaak 1899 - 1972 unification of Europe, supporting the European Coal and Steel Community and a European defence community. For Spaak, uniting countries through binding treaty obligations was the most effective means of guaranteeing peace and stability. He was able to help achieve these aims as president of the first full meeting of the United Nations (1946) and as Secretary General of NATO (1957-61). Spaak was a leading figure in formulating the content of the Treaty of Rome. At the ‘Messina Conference’ in 1955, the six participating governments appointed him president of the working committee that prepared the Treaty. Rise through Belgian politics Born on 25 January 1899 in Schaerbeek, Belgium, Paul-Henri Spaak Germans and spent the next two years imprisoned in a war camp.