Fencing Agricultural Land in Nigeria: Why Should It Be Done and How Can It Be Achieved?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nigeria Facts

FOUNDED August 28, 1907, in Seattle, USA ESTABLISHED IN Nigeria 1994 WORLD HEADQUARTERS Atlanta, USA ISMEA HEADQUARTERS Dubai, United Arab Emirates NIGERIA HEADQUARTERS Lagos, Nigeria COUNTRY MANAGER Ian Hood WEBSITE www.ups.com COUNTRY WEBSITE ups.com/ng GLOBAL VOLUME & REVENUE 2019 REVENUE $74 billion 2019 DELIVERY VOLUME 5.5 billion packages and documents DAILY DELIVERY VOLUME 21.9 million packages and documents DAILY U.S. AIR VOLUME 3.5 million packages and documents DAILY INTERNATIONAL VOLUME 3.2 million packages and documents EMPLOYEES 297 in Nigeria; 528,000 worldwide BROKERAGE & OPERATING FACILITIES 18 Lagos – Plot 16 Oworonshoki Expressway Gbagada Industrial Estate: Main Operations Center Lagos – LOS Murtala Mohammed International Airport SAHCOL Courier Shed, Ikeja: Brokerage Office Lagos -- 380 Ikorodu Road, Maryland: Warehouse/Supply Chain solutions Aba - Plot 2 Eziukwu Road Aba; Operations Center Abuja (Garki) - Plot 2196 Cadastral Zone A1, Area 3, Beside Savannah Suites; Operations Center Akure - 26 Oyemekun Road; Operations Center Benin - 34 Airport road; Transit Hub & Operations Center Calabar - 65 Ndidem Iso Rd; Operations Center Enugu - 87 Ogui Road; Operations Center Ibadan - 95 Moshood Abiola Way, Ring Rd; Operations Center Jos - 37 Rwam Pam; Operations Center Kaduna – 5 Ali Akilu Road; Transit Hub & Operations Center Kano - 61 Murtala Mohammed Way; Transit Hub & Operations Center Lokoja - KPC 313, Adankolo Junction; Transit Hub & Operations Center Onitsha - 99 Upper New Market; Transit Hub & Operations Center Owerri -

Cultural Landscape Adaptation And

NYAME AKUMA No. 72 December 2009 NIGERIA owner of the new farm. Berom men do this in turns until everyone has his own farm. But apart from pro- Cultural Landscape Adaptation and viding food for the work party, the wife or wives is/ Management among the Berom of are usually responsible for subsequent weeding in Central Nigeria order to ensure good harvests. The Berom people practice both cereal and tuber forms of agriculture. Samuel Oluwole Ogundele and James Local crops include millets, sorghum, cocoyam, po- Lumowo tato, cassava and yam. Berom farmers – men and Department of Archaeology and women – usually fence their farms with cacti. This is Anthropology an attempt to prevent the menace of domestic ani- University of Ibadan mals such as goats and sheep that often destroy Ibadan, Nigeria crops. [email protected] Apart from farming, the Berom men do practice hunting to obtain protein. Much of this game meat is also sold at the local markets. Hunting can be done Introduction on an individual or group basis. Some of the locally available game includes cane rats, monkeys, ante- This paper reports preliminary investigations lopes and porcupines. According to the available oral conducted in April and May 2009, of archaeological tradition, Beromland was very rich in animal resources and oral traditions among the Berom of Shen in the including tigers, elephants, lions and buffalos in the Du District of Plateau State, Nigeria. Berom people olden days. However, over-killing or indiscriminate are one of the most populous ethnicities in Nigeria. hunting methods using bows and arrows and spears Some of the districts in Beromland are Du, Bachi, have led to the near total disappearance of these Fan, Foron, Gashish, Gyel, Kuru, Riyom and Ropp. -

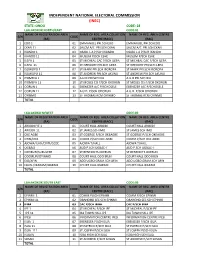

Ondo Code: 28 Lga:Akokok North/East Code:01 Name of Registration Area Name of Reg

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: ONDO CODE: 28 LGA:AKOKOK NORTH/EAST CODE:01 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 EDO 1 01 EMMANUEL PRI.SCHEDO EMMANUEL PRI.SCHEDO 2 EKAN 11 02 SALEM A/C PRI.SCH EKAN SALEM A/C PRI.SCH EKAN 3 IKANDO 1 03 OSABL L.A P/SCH IKANDO OSABL L.A P/SCH IKANDO 4 IKANDO 11 04 MUSLIM P/SCH ESHE MUSLIM P/SCH ESHE 5 ILEPA 1 05 ST MICHEAL CAC P/SCH ILEPA ST MICHEAL CAC P/SCH ILEPA 6 ILEPA 11 06 ST GREGORY PRI.SCH ILEPA ST GREGORY PRI.SCH ILEPA 7 ISOWOPO 1 07 ST MARK PRI.SCH IBOROPA ST MARK PRI.SCH IBOROPA 8 ISOWOPO 11 08 ST ANDREW PRI.SCH AKUNU ST ANDREW PRI.SCH AKUNU 9 IYOMEFA 1 09 A.U.D PRI.SCH IKU A.U.D PRI.SCH IKU 10 IYOMEFA 11 10 ST MOSES CIS P/SCH OKORUN ST MOSES CIS P/SCH OKORUN 11 OORUN 1 11 EBENEZER A/C P/SCHOSELE EBENEZER A/C P/SCHOSELE 12 OORUN 11 12 A.U.D. P/SCH ODORUN A.U.D. P/SCH ODORUN 13 OYINMO 13 ST THOMAS RCM OYINMO ST THOMAS RCM OYINMO TOTAL LGA:AKOKO N/WEST CODE:02 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ARIGIDI IYE 1 01 COURT HALL ARIGIDI COURT HALL ARIGIDI 2 ARIGIDI 11 02 ST JAMES SCH IMO ST JAMES SCH IMO 3 OKE AGBE 03 ST GOERGE P/SCH OKEAGBE ST GOERGE P/SCH OKEAGBE 4 OYIN/OGE 04 COMM.P/SCH OKE AGBE COMM.P/SCH OKE AGBE 5 AJOWA/ILASI/ERITI/GEDE 05 AJOWA T/HALL AJOWA T/HALL 6 OGBAGI 06 AUD P.SCH OGBAC-I AUD P.SCH OGBAC-I 7 OKEIRUN/SURULERE 07 ST BENEDICTS OKERUN ST BENEDICTS OKERUN 8 ODOIRUN/OYINMO 08 COURT HALL ODO IRUN COURT HALL ODO IRUN 9 ESE/AFIN 09 ADO UGBO GRAM.SCH AFIN ADO UGBO GRAM.SCH AFIN 10 EBUSU/IKARAM/IBARAM 10 COURT HALL IKARAM COURT HALL IKARAM TOTAL LGA:AKOKOK SOUTH EAST CODE:03 NAME OF REGISTRATION AREA NAME OF REG. -

A Historical Survey of Socio-Political Administration in Akure Region up to the Contemporary Period

European Scientific Journal August edition vol. 8, No.18 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 A HISTORICAL SURVEY OF SOCIO-POLITICAL ADMINISTRATION IN AKURE REGION UP TO THE CONTEMPORARY PERIOD Afe, Adedayo Emmanuel, PhD Department of Historyand International Studies,AdekunleAjasin University,Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria Abstract Thepaper examines the political transformation of Akureregion from the earliest times to the present. The paper traces these stages of political development in order to demonstrate features associated with each stage. It argues further that pre-colonial Akure region, like other Yoruba regions, had a workable political system headed by a monarch. However, the Native Authority Ordinance of 1916, which brought about the establishment of the Native Courts and British judicial administration in the region led to the decline in the political power of the traditional institution.Even after independence, the traditional political institution has continually been subjugated. The work relies on both oral and written sources, which were critically examined. The paper, therefore,argues that even with its present political status in the contemporary Nigerian politics, the traditional political institution is still relevant to the development of thesociety. Keywords: Akure, Political, Social, Traditional and Authority Introduction The paper reviews the political administration ofAkure region from the earliest time to the present and examines the implication of the dynamics between the two periods may have for the future. Thus,assessment of the indigenous political administration, which was prevalent before the incursion of the colonial administration, the political administration during the colonial rule and the present political administration in the region are examined herein.However, Akure, in this context, comprises the present Akure North, Akure South, and Ifedore Local Government Areas of Ondo State, Nigeria. -

POLICING REFORM in AFRICA Moving Towards a Rights-Based Approach in a Climate of Terrorism, Insurgency and Serious Violent Crime

POLICING REFORM IN AFRICA Moving towards a rights-based approach in a climate of terrorism, insurgency and serious violent crime Edited by Etannibi E.O. Alemika, Mutuma Ruteere & Simon Howell POLICING REFORM IN AFRICA Moving towards a rights-based approach in a climate of terrorism, insurgency and serious violent crime Edited by Etannibi E.O. Alemika, University of Jos, Nigeria Mutuma Ruteere, UN Special Rapporteur, Kenya Simon Howell, APCOF, South Africa Acknowledgements This publication is funded by the Ford Foundation, the United Nations Development Programme, and the Open Societies Foundation. The findings and conclusions do not necessarily reflect their positions or policies. Published by African Policing Civilian Oversight Forum (APCOF) Copyright © APCOF, April 2018 ISBN 978-1-928332-33-6 African Policing Civilian Oversight Forum (APCOF) Building 23b, Suite 16 The Waverley Business Park Wyecroft Road Mowbray, 7925 Cape Town, ZA Tel: +27 21 447 2415 Fax: +27 21 447 1691 Email: [email protected] Web: www.apcof.org.za Cover photo taken in Nyeri, Kenya © George Mulala/PictureNET Africa Contents Foreword iv About the editors v SECTION 1: OVERVIEW Chapter 1: Imperatives of and tensions within rights-based policing 3 Etannibi E. O. Alemika Chapter 2: The constraints of rights-based policing in Africa 14 Etannibi E.O. Alemika Chapter 3: Policing insurgency: Remembering apartheid 44 Elrena van der Spuy SECTION 2: COMMUNITY–POLICE NEXUS Chapter 4: Policing in the borderlands of Zimbabwe 63 Kudakwashe Chirambwi & Ronald Nare Chapter 5: Multiple counter-insurgency groups in north-eastern Nigeria 80 Benson Chinedu Olugbuo & Oluwole Samuel Ojewale SECTION 3: POLICING RESPONSES Chapter 6: Terrorism and rights protection in the Lake Chad basin 103 Amadou Koundy Chapter 7: Counter-terrorism and rights-based policing in East Africa 122 John Kamya Chapter 8: Boko Haram and rights-based policing in Cameroon 147 Polycarp Ngufor Forkum Chapter 9: Police organizational capacity and rights-based policing in Nigeria 163 Solomon E. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School DECOLONIZING HISTORY: HISTORICAL CONSCSIOUNESS, IDENTITY AND CIVIC ENGAGEMENT OF NIGERIAN YOUTH A Dissertation in Education Theory and Policy and Comparative and International Education by Rhoda Nanre Nafziger Ó 2020 Rhoda Nanre Nafziger Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2020 ii The dissertation of Rhoda Nanre Nafziger was reviewed and approved by the following: Mindy Kornhaber Associate Professor Education (Theory and Policy) Dissertation Co-Advisor Co-Chair of Committee Nicole Webster Associate Professor Youth and International Development, African Studies and Comparative and International Education Dissertation Co-Advisor Co-Chair of Committee David Gamson Associate Professor of Education (Theory and Policy) Rebecca Tarlau Assistant Professor of Education and Labor & Employment Relations Anthony Olorunnisola Professor of Media Studies and Associate Dean for Graduate Programs Kevin Kinser Department Head Education Policy Studies iii ABSTRACT Historical consciousness is the way in which we use knowledge of the past to inform our present and future actions. History and culture tie human societies together and provide them with reference points for understanding the past, present and future. Education systems that strip people from their culture and history are inherently violent as they attempt to alienate the individual from his or her cultural identity, separate them from their past and thus cultivate ruptures in the social fabric. Racism is a tool is used to justify neocolonialism and capitalist hegemony. As such, neocolonial education systems reproduce violence and social instability through the negation of history and culture. This dissertation examines the neocolonial and racist legacies in education in Africa through the analysis of Nigeria's history education policy and the historical consciousness of Nigerian youth. -

The Impact of English Language Proficiency Testing on the Pronunciation Performance of Undergraduates in South-West, Nigeria

Vol. 15(9), pp. 530-535, September, 2020 DOI: 10.5897/ERR2020.4016 Article Number: 2D0D65464669 ISSN: 1990-3839 Copyright ©2020 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article Educational Research and Reviews http://www.academicjournals.org/ERR Full Length Research Paper The impact of English language proficiency testing on the pronunciation performance of undergraduates in South-West, Nigeria Oyinloye Comfort Adebola1*, Adeoye Ayodele1, Fatimayin Foluke2, Osikomaiya M. Olufunke2, and Fatola Olugbenga Lasisi3 1Department of Education, School of Education and Humanities, Babcock University, Ilishan-Remo, Ogun State, Nigeria. 2Department of Arts and Social Science, Education Department, Faculty of Education, National Open University of Nigeria, Abuja, Nigeria. 3Educational Management and Business Studies, Department of Education, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago Iwoye, Ogun State, Nigeria. Received 2 June, 2020; Accepted 8 August, 2020 This study investigated the impact of English Language proficiency testing on the pronunciation performance of undergraduates in South-west. Nigeria. The study was a descriptive survey research design. The target population size was 1243 (200-level) undergraduates drawn from eight tertiary institutions. The instruments used for data collection were the English Language Proficiency Test and Pronunciation Test. The English Language proficiency test was used to measure the performance of students in English Language and was adopted from the Post-UTME past questions from Babcock University Admissions Office on Post Unified Tertiary Admissions and Matriculation Examinations screening exercise (Post-UTME) for undergraduates in English and Linguistics. The test contains 20 objective English questions with optional answers. The instruments were validated through experts’ advice as the items in the instrument are considered appropriate in terms of subject content and instructional objectives while Cronbach alpha technique was used to estimate the reliability coefficient of the English Proficiency test, a value of 0.883 was obtained. -

A VISION of WEST AFRICA in the YEAR 2020 West Africa Long-Term Perspective Study

Millions of inhabitants 10000 West Africa Wor Long-Term Perspective Study 1000 Afr 100 10 1 Yea 1965 1975 1850 1800 1900 1950 1990 2025 2000 Club Saheldu 2020 % of the active population 100 90 80 AGRICULTURAL SECTOR 70 60 50 40 30 NON AGRICULTURAL “INFORMAL” SECTOR 20 10 NON AGRICULTURAL 3MODERN3 SECTOR 0 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 Preparing for 2020: 6 000 towns of which 300 have more than 100 000 inhabitants Production and total availability in gigaczalories per day Import as a % of availa 500 the Future 450 400 350 300 250 200 A Vision of West Africa 150 100 50 0 1961 1963 1965 1967 1969 1971 1973 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 Imports as a % of availability Total food availability Regional production in the Year 2020 2020 CLUB DU SAHEL PREPARING FOR THE FUTURE A VISION OF WEST AFRICA IN THE YEAR 2020 West Africa Long-Term Perspective Study Edited by Jean-Marie Cour and Serge Snrech ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ FOREWoRD ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ In 1991, four member countries of the Club du Sahel: Canada, the United States, France and the Netherlands, suggested that a regional study be undertaken of the long-term prospects for West Africa. Several Sahelian countries and several coastal West African countries backed the idea. To carry out this regional study, the Club du Sahel Secretariat and the CINERGIE group (a project set up under a 1991 agreement between the OECD and the African Development Bank) formed a multi-disciplinary team of African and non-African experts. -

When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire Under Historial Review

Instructions for authors, subscriptions and further details: http://rimcis.hipatiapress.com When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire under Historial Review Matthias Olufemi Dada Ojo1 1) Crawford University of the Apostolic Faith Mission, Nigeria Date of publication: November 30th, 2014 Edition period: November 2014 – March 2015 To cite this article: Ojo, M.O.D. (2014). When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire under Historial Review. International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences, 3(3), 248-267. doi: 10.4471/rimcis.2014.39 To link this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.4471/rimcis.2014.39 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE The terms and conditions of use are related to the Open Journal System and to Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY). RIMCIS – International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences Vol. 3 No.3 November 2014 pp. 248-267 When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire under Historical Review Matthias Olufemi Dada Ojo Crawford University of the Apostolic Faith Mission Abstract Using historical events research approach and qualitative key informant interview, this study examined how religion failed to stop political crisis that happened in the old Western region of Nigeria. Ikire, in the present Osun State of Nigeria was used as a case study. The study investigated the incidences of killing, arson and exile that characterized the crisis in the town which served as the case study. It argued that the two prominent political figures which started the crisis failed to apply the religious doctrines of love, peace and brotherhood which would have solved the crisis before it spread to all parts of the Old Western Region of Nigeria and the entire nation. -

Factors Affecting Effective Teaching and Learning of Economics in Some Ogbomosho High Schools, Oyo State, Nigeria

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.7, No.28, 2016 Factors Affecting Effective Teaching and Learning of Economics in Some Ogbomosho High Schools, Oyo State, Nigeria Gbemisola Motunrayo Ojo Vusy Nkoyane Department of Curriculum and Instructional Studies, College of Education, University of South Africa 0001 Abstract This study was carried out to examine the present curriculum of Economics as a subject in some Ogbomoso Senior High Schools and to determine factors affecting effective teaching of economics in the schools. Variables such as number of students, teachers’ ratio available textbooks were also examined. The study adopted descriptive design since it is an ex post facto research. The target population for this study is Ogbomosho North Local Government Area of Oyo State comprising nine (9) High Secondary Schools. Three (3) teachers of economics and five (5) students from each school were used in answering the questionnaires. The study revealed high number of economics students (5,864) as against 26 teachers in nine (9) public schools under study. This gives a very high teacher-student ratio of 1:225. The findings also showed that there one lack of teaching aids, library facilities and where available, there is lack of textbooks of Economics. All the schools studied were highly dense resulted into high students’ population. Based on the findings of his study, the federal and the state governments should employ more teachers, especially in Economics to checkmate rising teacher student ratio. More senior secondary schools should be built with the increasing student population within the LGA under study. -

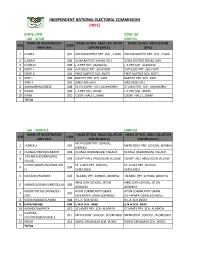

State: Oyo Code: 30 Lga : Afijio Code: 01 Name of Registration Name of Reg

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: OYO CODE: 30 LGA : AFIJIO CODE: 01 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ILORA I 001 OKEDIJI BAPTIST PRY. SCH., ILORA OKEDIJI BAPTIST PRY. SCH., ILORA 2 ILORA II 002 ILORA BAPTIST GRAM. SCH. ILORA BAPTIST GRAM. SCH. 3 ILORA III 003 L.A PRY SCH. ALAWUSA. L.A PRY SCH. ALAWUSA. 4 FIDITI I 004 CATHOLIC PRY. SCH FIDITI CATHOLIC PRY. SCH FIDITI 5 FIDITI II 005 FIRST BAPTIST SCH. FIDITI FIRST BAPTIST SCH. FIDITI 6 AWE I 006 BAPTIST PRY. SCH. AWE BAPTIST PRY. SCH. AWE 7 AWE II 007 AWE HIGH SCH. AWE HIGH SCH. 8 AKINMORIN/JOBELE 008 ST.JOHN PRY. SCH. AKINMORIN ST.JOHN PRY. SCH. AKINMORIN 9 IWARE 009 L.A PRY SCH. IWARE. L.A PRY SCH. IWARE. 10 IMINI 010 COURT HALL 1, IMINI COURT HALL 1, IMINI TOTAL LGA : AKINYELE CODE: 02 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) CENTRE (RACC) METHODIST PRY. SCHOOL, 1 IKEREKU 001 METHODIST PRY. SCHOOL, IKEREKU IKEREKU 2 OLANLA/OBODA/LABODE 002 OLANLA (OGBANGAN) VILLAGE OLANLA (OGBANGAN) VILLAGE EOLANLA (OGBANGAN) 3 003 COURT HALL ARULOGUN VILLAGE COURT HALL ARULOGUN VILLAGE VILLAG OLODE/AMOSUN/ONIDUND ST. LUKES PRY. SCHOOL, ST. LUKES PRY. SCHOOL, 4 004 U ONIDUNDU ONIDUNDU 5 OJO-EMO/MONIYA 005 ISLAMIC PRY. SCHOOL, MONIYA ISLAMIC PRY. SCHOOL, MONIYA ANGLICAN SCHOOL, OTUN ANGLICAN SCHOOL, OTUN 6 AKINYELE/ISABIYI/IREPODUN 006 AGBAKIN AGBAKIN IWOKOTO/TALONTAN/IDI- AYUN COMMUNITY GRAM. -

Characterization of Staphylococcus Aureus Isolates Obtained from Health Care Institutions in Ekiti and Ondo States, South-Western Nigeria

African Journal of Microbiology Research Vol. 3(12) pp. 962-968 December, 2009 Available online http://www.academicjournals.org/ajmr ISSN 1996-0808 ©2009 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolates obtained from health care institutions in Ekiti and Ondo States, South-Western Nigeria Clement Olawale Esan1, Oladiran Famurewa1, 2, Johnson Lin3 and Adebayo Osagie Shittu3, 4* 1Department of Microbiology, University of Ado-Ekiti, P.M.B. 5363, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria 2College of Science, Engineering and Technology, Osun State University, P.M.B. 4494, Osogbo, Nigeria 3School of Biochemistry, Genetics and Microbiology, University of KwaZulu-Natal (Westville Campus), Private Bag X54001, Durban, Republic of South Africa. 4Department of Microbiology, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria Accepted 5 November, 2009 Staphylococcus aureus is one of the major causative agents of infection in all age groups following surgical wounds, skin abscesses, osteomyelitis and septicaemia. In Nigeria, it is one of the most important pathogen and a frequent micro-organism obtained from clinical samples in the microbiology laboratory. Data on clonal identities and diversity, surveillance and new approaches in the molecular epidemiology of this pathogen in Nigeria are limited. This study was conducted for a better understanding on the epidemiology of S. aureus and to enhance therapy and management of patients in Nigeria. A total of 54 S. aureus isolates identified by phenotypic methods and obtained from clinical samples and nasal samples of healthy medical personnel in Ondo and Ekiti States, South-Western Nigeria were analysed. Typing was based on antibiotic susceptibility pattern (antibiotyping), polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphisms (PCR-RFLPs) of the coagulase gene and pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE).