Setbacks Advances

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RECURSO DO CONGRESSO NACIONAL No 2, DE 2014 (Do Sr

- - CÂMARA 66s DEPUTADOS RECURSO DO CONGRESSO NACIONAL No 2, DE 2014 (Do Sr. Jutahy Junior) Recurso interposto pelo Deputado Jutahy Junior da decisão desta Presidência sobre questão de ordem formulada por S. Exa na sessão conjunta realizada no dia dez dezembro de 2013. DESPACHO: NUMERE-SE COMO RECURSO E ENCAMINHE-SE A COMISSÃO DE CONSTITUIÇÁO E JUSTIÇA E DE CIDADANIA, NA FORMA DO ART. 132, 5 1°, DO REGIMENTO COMUM. PUBLIQUE-SE. Coordenaç%ode Comissões Permanentes - DECOM - 0369 Brasília, em 4 de fevereiro de 2014. Senhor Presidente, Nos termos do $ 1" do art. 132 do Regimento Comum, encaminho ag" e.,rt -T Vossa Excelência as Notas Taquigráficas da Sessão Conjunta de 10 de dezembrqs. %* de 2013, em face de recurso do Deputado JUTAHY JUNIOR contra deliberação6'&k. de questão de ordem formulada para impugnar a presidência dos trabalhos?R 3 ." zi$ exercida temporariamente pelo Deputado SIBÁ MACHADO. rn 5!! $ O SR. JUTAHY JUNIOR (PSDB - BA) - Sr. Presidente, só para 9 discordar de uma coisa: V. Ex" diz que não anula a sessão. Eu g gostaria de fazer um recurso para a Comissão de Justiça ... 5 O SR. PRESIDENTE (Andre Vargas. PT - PR) - Ótimo. 8.~ 3 O SR. JUTAHY JUNIOR (PSDB - BA) - ...porque existe matéria constitucional nessa questão, já foi debatido aqui por diversas vezes, - ejka aqui apresentado o recurso c3 Comissão de Justiça da Câmara 7 dos Deputados. Muito obrigado. Como se verá pelas notas, após a abertura dos trabalhos e decorrido tempo substancial do processo de votação do item 1, tive de ausentar-me temporariamente da Sessão, razão pela qual convoquei o Deputado Sibá Machado para assumir a Presidência, tendo em vista que nenhum outro membro da Mesa estava presente em Plenário naquele momento. -

Election for Federal Deputy in 2014 - a New Camera, a New Country1

Chief Editor: Fauze Najib Mattar | Evaluation System: Triple Blind Review Published by: ABEP - Brazilian Association of Research Companies Languages: Portuguese and English | ISSN: 2317-0123 (online) Election for federal deputy in 2014 - A new camera, a new country1 A eleição para deputados em 2014 - Uma nova câmara, um novo país Maurício Tadeu Garcia IBOPE Inteligência, Recife, PE, Brazil ABSTRACT In 2014 were selected representatives from 28 different parties in the House of Submission: 16 May 2016 Representatives. We never had a composition as heterogeneous partisan. Approval: 30 May 2016 However, there is consensus that they have never been so conservative in political and social aspects, are very homogeneous. Who elected these deputies? Maurício Tadeu Garcia The goal is to seek a given unprecedented: the profile of voters in each group of Post-Graduate in Political and deputies in the states, searching for differences and socio demographic Electoral Marketing ECA-USP and similarities. the Fundação Escola de Sociologia e Política de São Paulo (FESPSP). KEYWORDS: Elections; Chamber of deputies; Political parties. Worked at IBOPE between 1991 and 2009, where he returned in 2013. Regional Director of IBOPE RESUMO Inteligência. (CEP 50610-070 – Recife, PE, Em 2014 elegemos representantes de 28 partidos diferentes para a Câmara dos Brazil). Deputados. Nunca tivemos na Câmara uma composição tão heterogênea E-mail: partidariamente. Por outro lado, há consenso de que eles nunca foram tão mauricio.garcia@ibopeinteligencia conservadores em aspectos políticos e sociais, nesse outro aspecto, são muito .com homogêneos. Quem elegeu esses deputados? O objetivo deste estudo é buscar Address: IBOPE Inteligência - Rua um dado inédito: o perfil dos eleitores de cada grupo de deputados nos estados, Demócrito de Souza Filho, 335, procurando diferenças e similaridades sociodemográficas entre eles. -

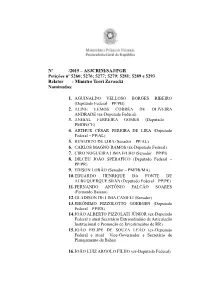

035 Pet5260 E

Nº /2015 – ASJCRIM/SAJ/PGR Petições nº 5260; 5276; 5277; 5279; 5281; 5289 e 5293 Relator : Ministro Teori Zavascki Nominados: 1. AGUINALDO VELLOSO BORGES RIBEIRO (Deputado Federal – PP/PB) 2. ALINE LEMOS CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA ANDRADE (ex-Deputada Federal) 3. ANIBAL FERREIRA GOMES (Deputado – PMDB/CE) 4. ARTHUR CÉSAR PEREIRA DE LIRA (Deputado Federal – PP/AL) 5. BENEDITO DE LIRA (Senador – PP/AL) 6. CARLOS MAGNO RAMOS (ex-Deputado Federal) 7. CIRO NOGUEIRA LIMA FILHO (Senador – PP/PI) 8. DILCEU JOÃO SPERAFICO (Deputado Federal – PP/PR) 9. EDISON LOBÃO (Senador – PMDB/MA) 10. EDUARDO HENRIQUE DA FONTE DE ALBUQUERQUE SILVA (Deputado Federal – PP/PE) 11. FERNANDO ANTÔNIO FALCÃO SOARES (Fernando Baiano) 12. GLADISON DE LIMA CAMELI (Senador) 13. JERÔNIMO PIZZOLOTTO GOERGEN (Deputado Federal – PP/RS) 14. JOÃO ALBERTO PIZZOLATI JÚNIOR (ex-Deputado Federal e atual Secretário Extraordinário de Articulação Institucional e Promoção de Investimentos de RR) 15. JOÃO FELIPE DE SOUZA LEÃO (ex-Deputado Federal e atual Vice-Governador e Secretário de Planejamento da Bahia) 16. JOÃO LUIZ ARGOLO FILHO (ex-Deputado Federal) PGR Pet5260 e outras_parlamentares e ex-parlamentares_2 17. JOÃO SANDES JUNIOR (Deputado Federal – PP/GO) 18. JOÃO VACCARI NETO (Tesoureiro do PT) 19. JOSÉ ALFONSO EBERT HAMM (Deputado Federal – PP/RS) 20. JOSÉ LINHARES PONTE (ex-Deputado Federal) 21. JOSÉ OLÍMPIO SILVEIRA MORAES (Deputado Federal – PP/SP) 22. JOSÉ OTÁVIO GERMANO (Deputado Federal – PP/RS) 23. JOSE RENAN VASCONCELOS CALHEIROS (SENADOR - PMDB-AL) 24. LÁZARO BOTELHO MARTINS (Deputado Federal – PP/TO) 25. LUIS CARLOS HEINZE (Deputado Federal – PP/RS) 26. LUIZ FERNANDO RAMOS FARIA (Deputado Federal – PP/MG) 27. -

REPORT Violence Against Indigenous Peoples in Brazil DATA for 2017

REPORT Violence against Indigenous REPORT Peoples in Brazil DATA FOR Violence against Indigenous Peoples in Brazil 2017 DATA FOR 2017 Violence against Indigenous REPORT Peoples in Brazil DATA FOR 2017 Violence against Indigenous REPORT Peoples in Brazil DATA FOR 2017 This publication was supported by Rosa Luxemburg Foundation with funds from the Federal Ministry for Economic and German Development Cooperation (BMZ) SUPPORT This report is published by the Indigenist Missionary Council (Conselho Indigenista Missionário - CIMI), an entity attached to the National Conference of Brazilian Bishops (Conferência Nacional dos Bispos do Brasil - CNBB) PRESIDENT Dom Roque Paloschi www.cimi.org.br REPORT Violence against Indigenous Peoples in Brazil – Data for 2017 ISSN 1984-7645 RESEARCH COORDINATOR Lúcia Helena Rangel RESEARCH AND DATA SURVEY CIMI Regional Offices and CIMI Documentation Center ORGANIZATION OF DATA TABLES Eduardo Holanda and Leda Bosi REVIEW OF DATA TABLES Lúcia Helena Rangel and Roberto Antonio Liebgott IMAGE SELECTION Aida Cruz EDITING Patrícia Bonilha LAYOUT Licurgo S. Botelho COVER PHOTO Akroá Gamella People Photo: Ana Mendes ENGLISH VERSION Hilda Lemos Master Language Traduções e Interpretação Ltda – ME This issue is dedicated to the memory of Brother Vicente Cañas, a Jesuit missionary, in the 30th year Railda Herrero/Cimi of his martyrdom. Kiwxi, as the Mỹky called him, devoted his life to indigenous peoples. And it was precisely for advocating their rights that he was murdered in April 1987, during the demarcation of the Enawenê Nawê people’s land. It took more than 20 years for those involved in his murder to be held accountable and convicted in February 2018. -

MINISTÉRIO PÚBLICO FEDERAL Excelentíssimo Senhor Procurador

MINISTÉRIO PÚBLICO FEDERAL Excelentíssimo Senhor Procurador-Geral da República A 6ª Câmara de Coordenação e Revisão do MPF, por meio de sua Coordenadora, vem representar criminalmente contra os Deputados federais Luís Carlos Heinze (PP/RS) e Alceu Moreira (PMDB/RS) pelas razões de fato e de direito a seguir deduzidas. Em novembro de 2013, em audiência pública ocorrida no município de Vicente Dutra, Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, os requeridos assim se manifestaram: Luís Carlos Heinze (PP/RS) - "No mesmo governo, seu Gilberto Carvalho, também ministro da presidenta Dilma. É ali que estão aninhados quilombolas, índios, gays, lésbicas, tudo que não presta ali tá aninhado, e eles têm a direção e têm o comando do governo". - "Se nós não fizermos nada, se vocês ficarem de braços cruzados, o que que vai acontecer? Então pessoal, o que que estão fazendo os produtores do Pará? No Pará, eles contrataram segurança privada. Ninguém invade no Pará porque a Brigada Militar não lhes dá guarida lá, e eles têm que fazer a defesa das suas propriedades. Por isso, pessoal só tem um jeito: se defendam! Façam a defesa como o Pará está fazendo, façam a defesa como o Mato Grosso do Sul está fazendo. Os índios invadiram uma propriedade, foram corridos da propriedade. Isso é o que aconteceu lá. Botaram um tratorzinho deles no meio da faixa. A defesa dos produtores tirou o trator e desobstruiu a faixa. Eles estão se defendendo. Se é isso que o governo quer, é isso que nós temos que fazer". - "Resolvemos os sem-terra lá em 2000 e vamos resolver os índios agora não interessa o tempo que seja". -

Senado Federal Proposta De Emenda À Constituição N° 19, De 2020

SENADO FEDERAL PROPOSTA DE EMENDA À CONSTITUIÇÃO N° 19, DE 2020 Introduz dispositivos ao Ato das Disposições Constitucionais Transitórias, a fim de tornar coincidentes os mandatos eletivos. AUTORIA: Senador Wellington Fagundes (PL/MT) (1º signatário), Senador Acir Gurgacz (PDT/RO), Senador Alvaro Dias (PODEMOS/PR), Senadora Mailza Gomes (PP/AC), Senadora Maria do Carmo Alves (DEM/SE), Senadora Rose de Freitas (PODEMOS/ES), Senadora Zenaide Maia (PROS/RN), Senador Ciro Nogueira (PP/PI), Senador Confúcio Moura (MDB/RO), Senador Eduardo Gomes (MDB/TO), Senador Elmano Férrer (PODEMOS/PI), Senador Irajá (PSD/TO), Senador Izalci Lucas (PSDB/DF), Senador Jayme Campos (DEM/MT), Senador Luis Carlos Heinze (PP/RS), Senador Major Olimpio (PSL/SP), Senador Marcelo Castro (MDB/PI), Senador Mecias de Jesus (REPUBLICANOS/RR), Senador Nelsinho Trad (PSD/MS), Senador Omar Aziz (PSD/AM), Senador Plínio Valério (PSDB/AM), Senador Rodrigo Pacheco (DEM/MG), Senador Romário (PODEMOS/RJ), Senador Sérgio Petecão (PSD/AC), Senador Telmário Mota (PROS/RR), Senador Weverton (PDT/MA), Senador Zequinha Marinho (PSC/PA) Página da matéria Página 1 de 9 Avulso da PEC 19/2020. SENADO FEDERAL Gabinete Senador Wellington Fagundes PROPOSTA DE EMENDA À CONSTITUIÇÃO Nº , DE 2020 Introduz dispositivos ao Ato das Disposições Constitucionais Transitórias, a fim de tornar coincidentes os mandatos eletivos. SF/20349.58524-23 As Mesas da Câmara dos Deputados e do Senado Federal, nos termos do § 3º do art. 60 da Constituição Federal, promulgam a seguinte emenda ao texto constitucional: Art. 1º O Ato das Disposições Constitucionais Transitórias fica acrescido de artigos, com a seguinte redação: “Art. 115. O mandato dos Prefeitos e dos Vereadores eleitos em 2016 terá a duração de seis anos. -

(Ou Discursos De Ódio?) De Parlamentares Contra Grupos Sociais Minoritários No Brasil

SILVA, Bruna Marques da. Discursos intolerantes (ou discursos de ódio?) de parlamentares contra grupos sociais minoritários no Brasil. Revista Eletrônica Direito e Política, Programa de Pós- Graduação Stricto Sensu em Ciência Jurídica da UNIVALI, Itajaí, v.15, n.3, 3º quadrimestre de 2020. Disponível em: www.univali.br/direitoepolitica - ISSN 1980-7791 DISCURSOS INTOLERANTES (OU DISCURSOS DE ÓDIO?) DE PARLAMENTARES CONTRA GRUPOS SOCIAIS MINORITÁRIOS NO BRASIL INTOLERABLE SPEECHES (OR HATE SPEECHES?) BY PARLIAMENTARIAN AGAINST MINORITY SOCIAL GROUPS IN BRAZIL Bruna Marques da Silva1 RESUMO Este estudo objetiva investigar se e como discursos intolerantes proferidos por parlamentares contra grupos sociais minoritários estão sendo enfrentados juridicamente no Brasil. Além disso, analisar se a definição de discurso de ódio referida pela Organização das Nações Unidas para a Educação, a Ciência e a Cultura (UNESCO) aproxima-se das manifestações objetos de demanda judicial. A pesquisa é de cunho exploratório, com levantamento bibliográfico e documental, bem como empírico, com análise de jurisprudência do Supremo Tribunal Federal. Os principais resultados da pesquisa apontam que: a) discursos intolerantes proferidos por parlamentares contra grupos sociais minoritários estão sendo judicializadas; b) nesses casos, o alcance da garantia da imunidade parlamentar material permanece conectado ao exercício da função parlamentar e c) por fim, os discursos intolerantes analisados tendem a aproximar-se do conceito jurídico de discurso de ódio referido pela Organização das Nações Unidas para a Educação, a Ciência e a Cultura (UNESCO); PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Direito à liberdade de expressão; Imunidade parlamentar; Discurso de ódio; Grupos sociais minoritários. ABSTRACT This article investigates whether and how intolerant speeches by parliamentarians against minority social groups are being approached legal in Brazil. -

Recibo De Entrega De Emendas À Loa

Data: 24111/2011 CONGRESSO NACIONAL COMISSÃO MISTA DE PLANOS, ORÇAMENTOS E FISCALIZAÇÃO Hora: 09:44 SISTEMA DE ELABORAÇÃO DE EMENDAS ÀS LEIS ORÇAMENTÁRIAS Página: 1 de 2 PLN 0028/ 2011 - LOA RECIBO DE ENTREGA DE EMENDAS À LOA EMENDA DE REMANEJAMENTO DE DESPESA NÚMERO UO TÍTULO LOCALIDADE VALOR DO EMENDA ACRÉSCIMO 12 53101 Apoio a Obras Preventivas de Desastres - Pernambuco 3.680.000 No Estado de Pernambuco (UF) EMENDA DE APROPRIAÇÃO DE DESPESA NÚMERO UO TÍTULO LOCALIDADE VALOR DO EMENDA ACRÉSCIMO 1 36901 Estruturação de Unidades de Atenção Pernambuco 150.000.000 Especializada em Saúde - No Estado de (UF) Pernambuco 2 30912 Apoio a Projetos de Interesse do Sistema Pernambuco 100.000.000 Nacional de Políticas sobre Drogas - No (UF) Estado de Pernambuco 3 54101 Apoio a Projetos de Infraestrutura Pernambuco 150.000.000 Turística - No Estado de Pernambuco (UF) 4 56101 Apoio a Projetos de Sistemas de Pernambuco 200.000.000 Transporte Coletivo Urbano - Obras e (UF) Ações de Apoio a Mobilidade Urbana e Trânsito Motorizado (de valor global INFERIOR a R$ 500 milhões) - No Estado de Pernambuco 5 24101 Apoio a Projetos de Tecnologias Social e Pernambuco 80.000.000 Assistiva - Em Municípios - No Estado de (UF) Pernambuco 6 36901 Serviços de Atenção às Urgências e Pernambuco 120.000.000 Emergências na Rede Hospitalar - No (UF) Estado de Pernambuco 7 53101 Apoio a Obras Preventivas de Desastres - Pernambuco 300.000.000 No Estado de Pernambuco (UF)· 8 56101 Apoio à Política Nacional de Recife-PE 30.000.000 Desenvolvimento Urbano - Obras e Ações de Infraestrutura -

Bmj | Elections

BMJ | ELECTIONS [email protected] (61) 3223-2700 VOTE COUNT Leading with a great 6,1% 2,7% advantage since the 0,0% 0,0% beginning of the votes 0,1% 0,6% count, Jair Bolsonaro (PSL) 0,8% 1,0% goes on the run-off after 1,2% 1,3% receiving more than 46% of 2,5% 4,8% the valid votes. Runner-up 12,5% 29,2% and Lula's political protégé, 46,1% Fernando Haddad (PT), proceeds to the second Null Blank João Goulart Filho (PPL) round but arrives at a Eymael (DC) Vera Lúcia (PSTU) Guilherme Boulos (PSOL) disadvantage with 18 million Alvaro Dias (Podemos) Marina Silva (Rede) Henrique Meirelles (MDB) fewer votes than Bolsonaro. Cabo Daciolo (Patriota) João Amoêdo (Novo) Geraldo Alckmin (PSDB) Ciro Gomes (PDT) Fernando Haddad (PT) Jair Bolsonaro (PSL) FIRST ROUND ANALYSIS The first round of the elections came to an end and was marked by the importance of social networks, especially Whatsapp, and by the amount of Fake News. Television time, an instrument hitherto used as a fundamental tool for consolidating votes has proved not to be individually enough to leverage a candidacy. PSDB's candidate Geraldo Alckmin made alliances with the center parties to get as much television time as possible, and because of the negative aspects of those alliances and the failure to identify voters' aspirations, he was not able to grow ST in the polls. Alckmin won the party election and lost the 1 ROUND TIMELINE popular election, with a hesitant and failed campaign and in being the anti-PT candidate and the third way. -

A Eleição Para Deputados Em 2014 - Uma Nova Câmara, Um Novo País1

Editor-Chefe: Fauze Najib Mattar | Sistema de avaliação: Triple Blind Review Publicação: Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa (ABEP) Idiomas: Português e Inglês | ISSN: 2317-0123 (on-line) A eleição para deputados em 2014 - Uma nova câmara, um novo país1 Election for federal deputy in 2014 - A new camera, a new country Maurício Tadeu Garcia IBOPE Inteligência, Recife, PE, Brasil RESUMO Em 2014 elegemos representantes de 28 partidos diferentes para a Câmara dos Submissão: 16 maio 2016 Deputados. Nunca tivemos na Câmara uma composição tão heterogênea Aprovação: 30 maio 2016 partidariamente. Por outro lado, há consenso de que eles nunca foram tão conservadores em aspectos políticos e sociais, nesse outro aspecto, são muito Maurício Tadeu Garcia homogêneos. Quem elegeu esses deputados? O objetivo deste estudo é buscar Pós-Graduado em Marketing um dado inédito: o perfil dos eleitores de cada grupo de deputados nos estados, Político e Eleitoral pela ECA-USP procurando diferenças e similaridades sociodemográficas entre eles. e pela Fundação Escola de Sociologia e Política de São Paulo PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Eleições; Câmara dos deputados; Partidos políticos. (FESPSP). Diretor Regional do IBOPE Inteligência. (CEP 50610-070 – Recife, PE, ABSTRACT Brasil). E-mail: In 2014 were selected representatives from 28 different parties in the House of mauricio.garcia@ibopeinteligencia Representatives. We never had a composition as heterogeneous partisan. .com However, there is consensus that they have never been so conservative in Endereço: IBOPE Inteligência - political and social aspects, are very homogeneous. Who elected these deputies? Rua Demócrito de Souza Filho, The goal is to seek a given unprecedented: the profile of voters in each group of 335, sala 901, 50610-070 - Recife, deputies in the states, searching for differences and socio demographic PE, Brasil. -

Supremo Tribunal Federal

Supremo Tribunal Federal URGENTE Ofício eletrônico nº 11169/2021 Brasília, 9 de agosto de 2021. A Sua Excelência o Senhor Presidente da Comissão Parlamentar de Inquérito do Senado Federal - CPI da Pandemia Medida Cautelar Em Mandado de Segurança n. 38130 IMPTE.(S) : BSF - BOLSA SAUDE & FUTURO EIRELI ADV.(A/S) : TICIANO FIGUEIREDO DE OLIVEIRA (23870/DF, 450957/SP) E OUTRO(A/S) IMPDO.(A/S) : COMISSÃO PARLAMENTAR DE INQUÉRITO DO SENADO FEDERAL - CPI DA PANDEMIA ADV.(A/S) : SEM REPRESENTAÇÃO NOS AUTOS (Processos Originários Cíveis) Senhor Presidente, De ordem, comunico-lhe os termos do(a) despacho/decisão proferido(a) nos autos em epígrafe, cuja reprodução segue anexa. Ademais, solicito-lhe as informações requeridas no referido ato decisório. Acompanha este expediente cópia integral do processo em referência. Informo que os canais oficiais do Supremo Tribunal Federal para recebimento de informações são: malote digital, fax (61- 3217-7921/7922) e Correios (Protocolo Judicial do Supremo Tribunal Federal, Praça dos Três Poderes s/n, Brasília/DF, CEP 70175-900). Apresento testemunho de consideração e apreço. Patrícia Pereira de Moura Martins Secretária Judiciária Documento assinado digitalmente Documento assinado digitalmente conforme MP n° 2.200-2/2001 de 24/08/2001. O documento pode ser acessado pelo endereço http://www.stf.jus.br/portal/autenticacao/autenticarDocumento.asp sob o código C464-E029-B671-BC86 e senha E5FA-67DA-5532-3FB0 EXCELENTÍSSIMO SENHOR MINISTRO PRESIDENTE DO SUPREMO TRIBUNAL FEDERAL BSF GESTÃO EM SAÚDE LTDA., pessoa jurídica de direito privada, inscrita no CNPJ/MF sob o nº 20.595.406/0001-71, com sede à Av. Tamboré, nº 267, 28º andar, Parte A, Torre Sul, CJ E 281 A-CCA, Bairro de Alphaville, Barueri-SP, CEP 06460-000, vem, respeitosamente, por seus advogados, à presença de vossa excelência, com fundamento nos art. -

Senadores Da República Nome Partido E-Mail Acir Marcos Gurgacz

Senadores da República Nome Partido E-mail Acir Marcos Gurgacz PDT / RO [email protected] Aécio Neves da Cunha PSDB / MG [email protected] Alfredo Pereira do PR / AM [email protected] Nascimento Aloysio Nunes Ferreira PSDB / SP [email protected] Filho Alvaro Fernandes Dias PSDB / PR [email protected] Ana Amélia de Lemos PP / RS [email protected] Ana Rita Esgario PT / ES [email protected] Angela Maria Gomes PT / RR [email protected] Portela Anibal Diniz PT / AC [email protected] Antonio Carlos Rodrigues PR / SP [email protected] Antonio Carlos Valadares PSB / SE [email protected] Armando de Queiroz PTB / PE [email protected] Monteiro Neto Ataídes de Oliveira PSDB / TO [email protected] Benedito de Lira PP / AL [email protected] Blairo Borges Maggi PR / MT [email protected] Casildo João Maldaner PMDB / SC [email protected] Cássio Rodrigues da PSDB / PB [email protected] Cunha Lima Cícero de Lucena Filho PSDB / PB [email protected] Ciro Nogueira Lima Filho PP / PI [email protected] Clésio Soares de Andrade PMDB / MG [email protected] Cristovam Ricardo PDT / DF [email protected] Cavalcanti Buarque Cyro Miranda Gifford PSDB / GO [email protected] Júnior Delcídio do Amaral PT / MS [email protected] Gomez Eduardo Alves do PSC / SE [email protected] Amorim Carlos Eduardo de Souza