Health Impact Assessment San Jose to Merced Corridor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

San Joaquin Regional Rail Commission Teleconference Board Meeting

Chair, Christina Fugazi, City of Stockton Commissioner, Nancy Young, City of Tracy Vice Chair, Leo Zuber, City of Ripon Commissioner, Kathy Miller, San Joaquin County Commissioner, Jose Nuño, City of Manteca Commissioner, Melissa Hernandez, Alameda County Commissioner, Lily Mei, City of Fremont Commissioner, Mikey Hothi, City of Lodi Executive Director, Stacey Mortensen SAN JOAQUIN REGIONAL RAIL COMMISSION TELECONFERENCE BOARD MEETING June 4, 2021 – 8:00 am Call-In Information: +1 (646) 749-3122 Access Code: 185-391-325 GoToMeeting Link: https://global.gotomeeting.com/join/185391325 SPECIAL NOTICE Coronavirus COVID-19 In accordance with the Governor’s Executive Order N-29-20, San Joaquin Regional Rail Commission Board Members will be attending this meeting via teleconference or videoconference. Members of the public may observe the meeting by dialing +1 (646) 749- 3122 with access code: 185-391-325 or log-in using a computer, tablet or smartphone at GoToMeeting.com using link: https://global.gotomeeting.com/join/185391325 Please note that all members of the public will be placed on mute until such times allow for public comments to be made. If a person wishes to make a public comment during the meeting, to do so they must either 1) use GoToMeeting and will have the option to notify SJRRC staff by alerting them via the “Chat” function or they can 2) contact SJRRC staff via email at [email protected] in which staff will read the comment aloud during the public comment period. Emailed public comments should be limited to approximately 240 words as comments will be limited to two (2) minutes per comment. -

Megaregion Working Group Agenda

MEGAREGION WORKING GROUP AGENDA Friday, June 25, 2021 12:30 PM – 2:30 PM SUPERVISOR ALFREDO PEDROZA, NAPA COUNTY Meeting location – (Vice-Chair) You are invited to a Zoom Meeting SUPERVISOR NATE Join from a PC, Mac, iPad, iPhone or Android device: MILEY, ALAMEDA COUNTY Please click this URL to join. https://sjcog.zoom.us/j/98750744809 SUPERVISOR JIM SPERING, SOLANO COUNTY Or Telephone: (669) 900-6833 MAYOR AMY Webinar ID: 987 5074 4809 WORTH, CITY OF ORINDA 1. Call to Order/ Roll Call of MegaRegion Members 2. Presentation - John Robert Smith, Transportation for America 3. Refresh of March Meeting; June Agenda Overview & Purpose– Diane Nguyen, SJCOG SUPERVISOR ROBERT Executive Director RICKMAN, SAN JOAQUIN COUNTY (Chair) 4. Candidate Megaregion Capital Project Priorities—Discussion led by agency staff. VICE-MAYOR GARY SINGH, CITY OF MANTECA 5. Spotlight - Planning/Project Concept Priorities –Discussion led by Executive Directors. MAYOR NANCY YOUNG, CITY OF TRACY 6. Public Communications – anyone person wishing to address the megaregion working COUNCILMEMBER group on non-agendized items may do so at this time. Please use the “raise hand” LEO ZUBER, CITY OF RIPON feature (for video participants) or press *9 for phone participants. 7. Wrap up/next steps for September –Diane Nguyen, SJCOG Executive Director 8. Adjourn to next meeting at 12:30 p.m. to 2:30 p.m., September 24, 2021. SUPERVISOR BONNIE GORE, PLACER COUNTY MAYOR MIKE KOZLOWSKI, CITY OF FOLSOM COUNCILMEMBER LUCAS FRERICHS, CITY OF DAVIS SUPERVISOR DON SAYLOR, YOLO COUNTY 1 Agenda Item #3 Refresh of March Meeting 2 MEGAREGION GROUP APPROVED FRAMEWORK FOR MEGAREGION TRANSPORTATION INVESTMENT STRATEGY (Approved at March 26, 2021 meeting) Objective: To develop a set of “framing principles” that will guide potential shared interests in transportation investments among the megaregional partners. -

5-26-17 Joint Powers Authority Agenda

Supervisor Vito Chiesa, Chair, Stanislaus County Alternate Richard O’Brien, City of Riverbank Councilmember Don Tatzin, Vice-Chair, City of Lafayette Alternate Federal Glover, Contra Costa County Councilmember Patrick Hume, Vice-Chair, City of Elk Grove Alternate Don Nottoli, Sacramento County Supervisor Rodrigo Espinoza, Merced County Alternate Mike Villalta, City of Los Banos Supervisor Scott Haggerty, Alameda County Alternate Tom Blalock, BART Councilmember Bob Johnson, City of Lodi Alternate Bob Elliott, San Joaquin County Supervisor Doug Verboon, Kings County Alternate Justin Mendes, City of Hanford Supervisor Brett Frazier, Madera County Alternate Andrew Medellin, City of Madera Supervisor Sal Quintero, Fresno County Alternate Michael Derr, City of Selma Supervisor Amy Shuklian, Tulare County Alternate Bob Link, City of Visalia AGENDA May 26, 2017 – 1:00 PM Fresno County Board of Supervisors Chambers 2281 Tulare Street, Fresno CA San Joaquin Joint Powers Sacramento County Authority Administration Building 36437 East Ridge Road 949 East Channel Street 700 H Street, Suite 2450 Sea Ranch, CA 95497 Stockton, CA 95202 Sacramento, CA 95814 This Agenda shall be made available upon request in alternative formats to persons with a disability, as required by the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (42 U.S.C. § 12132) and the Ralph M. Brown Act (California Government Code § 54954.2). Persons requesting a disability related modification or accommodation in order to participate in the meeting should contact San Joaquin Regional Rail Commission staff, at 209-944-6220, during regular business hours, at least twenty-four hours prior to the time of the meeting. All proceedings before the Authority are conducted in English. -

DRAFT Findings of Effect Stockton San Francisco

Project Environmental Impact Report / Environmental Impact Statement Merced to Fresno Section Project EIR/EIS Sacramento DRAFT Findings of Effect Stockton San Francisco Millbrae-SFO Modesto Redwood City/Palo Alto San Jose Merced (Potential Station) Gilroy Fresno March 2012 Kings/Tulare (Potential Station) Bakersfield Palmdale East San Fernando/Burbank San Gabriel Valley Ontario Airport Los Angeles Riverside/Corona Norwalk Anaheim Murrieta Escondido San Diego California High-Speed Train Project EIR/EIS DRAFT Merced to Fresno Section Findings of Effect Prepared by: California High-Speed Rail Authority and Federal Railroad Administration March 2012 CALIFORNIA HIGH-SPEED TRAIN PROJECT EIR/EIS DRAFT FINDINGS OF EFFECT MERCED TO FRESNO SECTION CONTENTS Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations ....................................................................................... vii 1.0 Summary of Findings .......................................................................................1-1 2.0 Description of the Undertaking .......................................................................2-1 2.1 Preferred Alternative ......................................................................................... 2-1 3.0 Consulting Parties, Public Participation ..........................................................3-1 4.0 Description of Historic Properties, Application of Criteria of Adverse Effect, and Conditions Proposed .................................................................................4-1 4.1 Methodology ................................................................................................... -

Presentation

October 20, 2017 Meeting San Joaquin Valley Rail Committee 1. Introductions Steve Cohn, Chair San Joaquin Valley Rail Committee 2. Public Comment Steve Cohn, Chair San Joaquin Valley Rail Committee 3. Amtrak San Joaquins Operations Update Daniel Krause SAN JOAQUINS ON-TIME PERFORMANCE On-Time Performance FY12 – FY16 100.0% 90.0% 88.1% 84.0% 80.0% 77.7% 75.4% 76.5% 73.6% 70.0% 60.0% 50.0% FY12 FY13 FY14 FY15 FY16 FY17 SAN JOAQUINS ON-TIME PERFORMANCE On-Time Performance FY17 100.00% 88.70% 90.00% 85.70% 81.20% 80.70% 79.50% 81.00% 78.60% 80.00% 77.90% 71.20% 70.00% 65.70% 66.30% 61.40% 60.00% 50.00% 40.00% 30.00% 20.00% 10.00% 0.00% SAN JOAQUINS RIDERSHIP Ridership Ticket Revenue Month FY17 FY16 % Chg. FY17 FY16 % Chg. Oct 87,454 90,961 -3.9 $2,769,402 $2,756,890 +0.5 Nov 101,672 102,915 -1.2 $3,538,396 $3,609,485 -2.0 Dec 98,053 97,530 +0.5 $3,378,587 $3,415,503 -1.1 Jan 82,707 82,475 +0.3 $2,608,201 $2,643,805 -1.3 Feb 76,288 80,868 -5.7 $2,253,335 $2,424,039 -7.0 Mar 92,019 97,167 -5.3 $2,906,099 $3,118,374 -6.8 Apr 102,440 84,968 +20.6 $3,097,819 $2,529,587 +22.5 May 95,894 96,630 -0.8 $2,961,079 $2,904,982 +1.9 Jun 98,158 97,844 +0.3 $3,088,761 $3,032,447 +1.9 Jul 104,088 107,120 -2.8 $3,317,878 $3,327,313 -0.3 Aug 95,909 94,932 +1.0 $3,050,003 $3,004,462 +1.5 Sep 85,355 88,891 -4.0 $2,733,361 $2,818,684 -3.0 YTD 1,120,037 1,122,301 -0.2 $35,702,920 $35,585,570 +0.3 SAN JOAQUINS RIDERSHIP FY16 v. -

2-5-21 SJRRC Agenda Packet

Chair, Christina Fugazi, City of Stockton Commissioner, Nancy Young, City of Tracy Vice Chair, Leo Zuber, City of Ripon Commissioner, Kathy Miller, San Joaquin County Commissioner, Jose Nuno, City of Manteca Commissioner, Melissa Hernandez, Alameda County Commissioner, Lily Mei, City of Fremont Commissioner, Mikey Hothi, City of Lodi Executive Director, Stacey Mortensen SAN JOAQUIN REGIONAL RAIL COMMISSION TELECONFERENCE BOARD MEETING February 5, 2021 – 8:00 am Call-In Information: +1 (571) 317-3122 Access Code: 314-618-965 GoToMeeting Link: https://global.gotomeeting.com/join/314618965 SPECIAL NOTICE Coronavirus COVID-19 In accordance with the Governor’s Executive Order N-29-20, San Joaquin Regional Rail Commission Board Members will be attending this meeting via teleconference or videoconference. Members of the public may observe the meeting by dialing +1 (571) 317- 3122 with access code: 314-618-965 or log-in using a computer, tablet or smartphone at GoToMeeting.com using link: https://global.gotomeeting.com/join/314618965 Please note that all members of the public will be placed on mute until such times allow for public comments to be made. If a person wishes to make a public comment during the meeting, to do so they must either 1) use GoToMeeting and will have the option to notify SJRRC staff by alerting them via the “Chat” function or they can 2) contact SJRRC staff via email at [email protected] in which staff will read the comment aloud during the public comment period. Emailed public comments should be limited to approximately 240 words as comments will be limited to two (2) minutes per comment. -

Land Use Plans, Goals, and Policies

APPENDIX 3.13-A Land Use Plans, Goals, and Policies CALIFORNIA HIGH-SPEED TRAIN PROJECT EIR/EIS APPENDIX 3.13-A MERCED TO FRESNO SECTION LAND USE PLANS, GOALS, AND POLICIES 1.0 Land Use Plans, Goals, and Policies 1.1 Introduction A review of state, regional, and local land use plans identified goals, objectives, and/or policies pertinent to the Merced to Fresno Section of the HST Project. The HST Project is a state project and is not subject to mandatory consistency with local land use plans or local zoning ordinances under CEQA. However, analysis was performed to identify those regional and local goals and policies related to the HST Project and to identify any inconsistencies only in the regional plans that could result in potential environmental impacts. The following sections summarize the related plans. Table 3.13A-1 (at the end of this section) lists the specific goals, objectives, and policies in the plans and discusses the project with them. The table includes only those policies that are relevant to the project. 1.2 State Land Use Plans State law requires that local governments (cities and counties) adopt general plans to guide local growth and development. The following section describes relevant general plans and the local regulatory setting. 1.3 Summaries of Local Land Use Plans 1.3.1 City of Atwater General Plan The City of Atwater General Plan (City of Atwater 2000) presents a vision of the city for the year 2020 and represents a community consensus. It is a guide for citizens and city officials for discussions about community growth and development, and it provides a framework for decisions on those issues. -

AGENDA January 25, 2019 – 1:00 P.M

Supervisor Vito Chiesa, Chair, Stanislaus County Alternate Richard O’Brien, City of Riverbank Councilmember Patrick Hume, Vice-Chair, City of Elk Grove Alternate Don Nottoli, Sacramento County Councilmember Kevin Romick, City of Oakley Alternate David Hudson, City of San Ramon Supervisor Rodrigo Espinoza, Merced County Alternate Mike Villalta, City of Los Banos Supervisor Scott Haggerty, Alameda County Alternate Bob Elliott, San Joaquin County Councilmember Bob Johnson, City of Lodi Alternate David Ayers, City of Hanford Supervisor Doug Verboon, Kings County Alternate Andrew Medellin, City of Madera Supervisor Brett Frazier, Madera County Alternate Bob Link, City of Visalia Supervisor Sal Quintero, Fresno County Supervisor Amy Shuklian, Tulare County AGENDA January 25, 2019 – 1:00 P.M. Fresno County Board of Supervisors Chambers 2281 Tulare Street, 3rd Floor, Fresno CA, 93721 Oakland Administrative Elk Grove City Hall Livingston City Hall Building Conference Room 3C Conference Room A nd 1311 Midvale Ave., 1221 Oak Street, (2 Floor) 1416 C Street, 8401 Laguna Palms Livingston, CA Lodi, CA Oakland, CA Way, Elk Grove, CA This Agenda shall be made available upon request in alternative formats to persons with a disability, as required by the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (42 U.S.C. § 12132) and the Ralph M. Brown Act (California Government Code § 54954.2). Persons requesting a disability related modification or accommodation in order to participate in the meeting should contact San Joaquin Regional Rail Commission staff, at 209-944-6220, during regular business hours, at least twenty-four hours prior to the time of the meeting. All proceedings before the Authority are conducted in English. -

11-22-19 SJJPA Agenda Packet

Supervisor Vito Chiesa, Chair, Stanislaus County Alternate Richard O’Brien, City of Riverbank Councilmember Patrick Hume, Vice-Chair, City of Elk Grove Alternate Don Nottoli, Sacramento County Supervisor Scott Haggerty, Vice-Chair, Alameda County Councilmember Kevin Romick, City of Oakley Alternate David Hudson, City of San Ramon Supervisor Rodrigo Espinoza, Merced County Alternate Daron McDaniel, Merced County Councilmember Bob Johnson, City of Lodi Alternate Bob Elliott, San Joaquin County Supervisor Doug Verboon, Kings County Alternate Francisco Ramirez, City of Hanford Supervisor Brett Frazier, Madera County Alternate Andrew Medellin, City of Madera Supervisor Sal Quintero, Fresno County Alternate Rey Leon, City of Huron Supervisor Amy Shuklian, Tulare County Alternate Bob Link, City of Visalia REVISED AGENDA November 22nd, 2019 – 1:15 PM Merced County Board of Supervisors Chambers 2222 M Street 3rd Floor, Merced, CA, 95340 Call-In Locations Heritage House Alameda County 1311 Midvale Road County of Alameda Administration Bldg. Lodi, CA 4501 Pleasanton 1221 Oak Street Ste. 95240 Ave., Pleasanton, CA 536, Oakland, CA 94566 94612 This Agenda shall be made available upon request in alternative formats to persons with a disability, as required by the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (42 U.S.C. § 12132) and the Ralph M. Brown Act (California Government Code § 54954.2). Persons requesting a disability related modification or accommodation in order to participate in the meeting should contact San Joaquin Regional Rail Commission staff, at 209-944-6220, during regular business hours, at least twenty-four hours prior to the time of the meeting. All proceedings before the Authority are conducted in English. -

ACE Ceres–Merced Extension Project PUBLIC REVIEW PERIOD: THURSDAY, APRIL 22, 2021 – MONDAY, JUNE 7, 2021 DATE: April 22, 2021

NOTICE OF AVAILABILITY OF A DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT REPORT ACE Ceres–Merced Extension Project PUBLIC REVIEW PERIOD: THURSDAY, APRIL 22, 2021 – MONDAY, JUNE 7, 2021 DATE: April 22, 2021 TO: Agencies, Organizations, and Interested Parties FROM: San Joaquin Regional Rail Commission SUBJECT: Notice of Availability of a Draft Environmental Impact Report (Draft EIR) for the ACE Ceres- Merced Extension Project (SCH #2018012014) NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that the San Joaquin Regional Rail Commission (SJRRC), acting as lead agency under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), has prepared a Draft EIR for the Altamont Corridor Express (ACE) Ceres–Merced Extension Project (Project). A. Project Description SJRRC proposes to extend ACE passenger rail service along approximately 34-miles from Ceres to Merced. The Proposed Project would include the development of the following facilities. • The Ceres to Merced Extension Alignment, which consists of upgrades to track, new track, and bridges within the Union Pacific Railroad (UPRR) Fresno Subdivision between Ceres and Merced.1 • The Turlock, Livingston, and Merced Stations, which are located along the Ceres to Merced Extension Alignment. • The Merced Layover & Maintenance Facility, which is located in north Merced to support extension operations. Project Alignment, Stations, and Layover & Maintenance Facility Ceres to Merced Extension Alignment The proposed extension to Merced would construct a combination of track upgrades and new track, which would result in a second mainline on the UPRR Fresno Subdivision between Ceres and Merced. These proposed track upgrades and new track for the Ceres to Merced Extension Alignment would be located east or west of the existing mainline track. Approximately 26 miles of new mainline track will be installed as part of the Project and will be located between existing sidings, which will also be upgraded. -

The Citizens for California High-Speed Rail Accountability

CCH April 8, 2014 CITIZENS FOR CALIFORNIA HIGH SPEED RAIL ACCOUNTABILITY Post Office Box 881, Hanford, California 93232 [email protected] Email 559-469-6685 cchsra.org Website CAAHSR Facebook @CCHSRA Twitter CALIFORNIA HIGH-SPEED RAIL AUTHORITY 770 L-Street, Suite-880 Sacramento, California 95814 Attention: Board Members Regarding: REALISTIC VIEW OF THE CALIFORNIA HIGH-SPEED RAIL AUTHORITY'S 2014 BUSINESS PLAN Attached is a realistic view of the California High-Speed Train Project (CHSTP). Where it has been and where it appears the Authority is planning to take it. In 2008, the CHSTP was defined by California Assembly Bill-3034 and the resulting Proposition-1A. Since then, we the public, law makers and the media have been saturated by the California High-Speed Rail Authority's promises and marketing campaigns to build something different than what the public agreed to fund. The Sacramento Superior Court has ruled that to be the case. The state has appealed the Superior Court's finding and we are eagerly ready to defend the Court's ruling. The state's lack of compliance with the law is a non-complex matter for the appellate court to review and come to the same finding as the lower court. The Authority's 2014 Business Plan just re-enforces how far the CHSTP has drifted from what the public authorized by now pursuing critical Green House Gas (GHG) revenues that should be used by law to meet the state's 2020 GHG reduction goals. California Assembly Bill-32 (AB32) is just another funding law that the Authority is prepared to bleed out to justify its continued existence. -

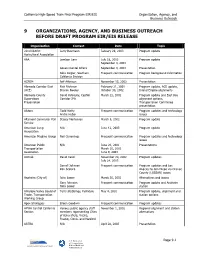

9 Organizations, Agency, and Business Outreach Before Draft Program Eir/Eis Release

California High-Speed Train Final Program EIR/EIS Organization, Agency, and Business Outreach 9 ORGANIZATIONS, AGENCY, AND BUSINESS OUTREACH BEFORE DRAFT PROGRAM EIR/EIS RELEASE Organization Contact Date Topic 22nd District Larry Baumann January 29, 2003 Program update Agricultural Association AAA Lewison Lem July 18, 2003 Program update September 4, 2003 Governmental Affairs September 4, 2003 Presentation John Zeigler, Southern Frequent communication Program background information California Division ACREM Jeff Atkinson November 13, 2002 Presentation Alameda Corridor East Rick Richman February 21, 2001 Program update, ACE update, (ACE) Sharon Neeley October 30, 2002 Inland Empire alignments Alameda County David Kutrosky, Captiol March 22, 2002 Program update and East Bay Supervisors Corridor JPA alignment options, Presentation Transportation Committee presentation Alstom Todd Welty Frequent communication Program updates and technology Andre Huber issues Altamont Commuter Rail Stacey Mortensen March 6, 2002 Program update Service American Lung N/A June 12, 2003 Program update Association American Magline Group Neil Cummings Frequent communication Program updates and technology issues American Public N/A June 20, 2001 Presentations Transportation March 10, 2003 Association June 9, 2003 Amtrak David Carol November 20, 2002 Program updates July 24, 2003 Darrell Johnson Frequent communication Program updates and Los Ron Scolaro Angeles to San Diego via Orange County (LOSSAN) issues Anaheim (City of) John Lower March 30, 2001 Alternatives and