Temporal and Spatial Differences in the Post-Breeding Behaviour of A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seabird Year-Round and Historical Feeding Ecology: Blood and Feather Δ13c and Δ15n Values Document Foraging Plasticity of Small Sympatric Petrels

Vol. 505: 267–280, 2014 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published May 28 doi: 10.3354/meps10795 Mar Ecol Prog Ser FREEREE ACCESSCCESS Seabird year-round and historical feeding ecology: blood and feather δ13C and δ15N values document foraging plasticity of small sympatric petrels Yves Cherel1,*, Maëlle Connan1, Audrey Jaeger1, Pierre Richard2 1Centre d’Etudes Biologiques de Chizé, UMR 7372 du CNRS et de l’Université de La Rochelle, BP 14, 79360 Villiers-en-Bois, France 2Laboratoire Littoral, Environnement et Sociétés, UMR 7266 du CNRS et de l’Université de La Rochelle, 2 rue Olympe de Gouges, 17000 La Rochelle, France ABSTRACT: The foraging ecology of small seabirds remains poorly understood because of the dif- ficulty of studying them at sea. Here, the extent to which 3 sympatric seabirds (blue petrel, thin- billed prion and common diving petrel) alter their foraging ecology across the annual cycle was investigated using stable isotopes. δ13C and δ15N values were used as proxies of the birds’ foraging habitat and diet, respectively, and were measured in 3 tissues (plasma, blood cells and feathers) that record trophic information at different time scales. Long-term temporal changes were inves- tigated by measuring feather isotopic values from museum specimens. The study was conducted at the subantarctic Kerguelen Islands and emphasizes 4 main features. (1) The 3 species highlight a strong connection between subantarctic and Antarctic pelagic ecosystems, because they all for- aged in Antarctic waters at some stages of the annual cycle. (2) Foraging niches are stage- dependent, with petrels shifting their feeding grounds during reproduction either from oceanic to productive coastal waters (common diving petrel) or from subantarctic to high-Antarctic waters where they fed primarily on crustaceans (blue petrel and thin-billed prion). -

Maximum Dive Depths of the Peruvian Divin-Petrel

1002 SHORT COMMUNICATIONS The Condor 99:1002-1004 0 The Cooper Omlthological Society 1997 MAXIMUM DIVE DEPTHS OF THE PERUVIAN DIVING-PETREL’ CARLOS B. ZAVALAGA Av. Guardia Chalaca 1333, Callao, Peru, e-mail: [email protected] JAIME JAHNCKE~ Institute de1 Mar de1 Peru ’ (IMARPE), Apartado 22, Callao, Peru, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The mean maximum dive depth attained METHODS for 22 adult Peruvian Diving-petrels (Pelecanoides The field work was carried out on La Vieja Island, garnotii) was 31.6 + 3.6 m. The deepestdive was 83.1 Peru (14”16’S, 76”ll’W) from August 1995 to May m. This maximum dive depth was 81% deeper than 1996. The island lies at the entranceof Independencia that predicted by its body size (46 m) and the deepest Bay, about 50 km south of the ParacasPeninsula. reported for a seabird weighing less than 210 g. Depth gauges were deployed on 66 adult birds at Key words: Peruvian Diving-petrels, diving different stagesof the breeding cycle (incubation and depths, foraging behavior, Pelecanoidesgamotii. chick rearing). Adults were capturedin their burrows, weighed, measured,and ringed. Gaugeswere attached to feathersin the center of the bird’s back using quick- The maximum dive depth of several taxa of free-living set epoxy glue (Devcon 5-minute epoxy). The devices seabirdshas been successfullydetermined using cap- were retrieved after l-3 days. illary-tube gauges. Although these devices provide Capillary-tube depth gauges, similar to those de- only the record of the deepest dives, which normally scribed by Burger and Wilson (1988), consistedof a 6 represent less frequent exploratory dives beyond the cm length of flexible, clear PVC tubing (internal di- animal’s normal foraging depths (Lishman and Croxall ameter of 0.8 mm), coated internally with a thin layer 1983. -

Birding the Humboldt Current

BIRDING THE HUMBOLDT CURRENT We will visit the guano bird colonies of the San Lorenzo, Palomino and Cavinzas Islands, observe pelagic birds that only live offshore, we will see the huge colony of sea lions of the Palomino Islands and observe different species of cetaceans. South American Sea Lion colony | © Jean Paul Perret ITINERARY 05:40 AM Encounter at the dock and registration of the participants. 06:00 AM Boarding from the Marina Yacht Club del Callao ( location map ), located half a block from Plaza Grau in Callao, not to be confused with the La Punta club. 06:30 AM Visit to the colonies of guano birds of San Lorenzo Island. 08:00 AM Start of the “chum " bait session 16 miles from the coast. 10: 00 AM Start of return to port. 11: 00 PM Arrival at the Marina Yacht Club Del Callao. TOUR DESCRIPTION The tour begins with a short navigation to Cabezo Norte sector of San Lorenzo Island, the largest island of the Peruvian coast; at its summit we will see the Gran Almirante Grau Lighthouse. Later we will begin to observe some very interesting species of birds such as the Humboldt Penguin, the Red-legged Cormorant, Peruvian Booby, Peruvian Pelican, Guanay Cormorant, Inca Tern, Blackish Oystercatcher and the endemic Surf Cinclodes. According to the season we can also find some migratory species such as the Surfbirds, Ruddy Turnstone, Whimbrel, Royal Tern, and Elegant Tern. Humboldt Penguins | © Jean Paul Perret From this point we will go into the sea in a journey of one hour. During the navigation we will start to observe some pelagic birds such as the Peruvian Diving-petrel, Sooty Shearwaters, Pink-footed Shearwater, Wilson's Storm-petrel, Swallow-tailed Gull, Sabine's Gull, Chilean Skua, Parasite Jaeger, Phalarops and with a bit of luck Waved Albatross. -

Species List

Antarctica Trip Report November 30 – December 18, 2017 | Compiled by Greg Smith With Greg Smith, guide, and participants Anne, Karen, Anita, Alberto, Dick, Patty & Andy, and Judy & Jerry Bird List — 78 Species Seen Anatidae: Ducks, Geese, and Swans (8) Upland Goose (Chloephaga picta) Only seen on the Falklands, and most had young or were on nests. Kelp Goose (Chloephaga hybrid) On the beach (or close to the beach) at West Point and Carcass Islands. Ruddy-headed Goose (Chloephaga rubidiceps) Mixed in with the grazing Upland Geese on the Falklands. Flightless Steamer Duck (Tachyeres pteneres) Found on both islands that we visited, and on Stanley. Crested Duck (Lophonetta specularioides) Not common at all with only a few seen in a pond on Carcass Island. Yellow-billed (Speckled) Teal (Anas flavirostris) Two small flocks were using freshwater ponds. Yellow-billed Pintail (Anas georgica) Fairly common on South Georgia. South Georgia Pintail (Anas georgica georgica) Only on South Georgia and seen on every beach access. Spheniscidae: Penguins (7) King Penguin (Aptenodytes patagonicus) Only on South Georgia and there were thousands and thousands. Gentoo Penguin (Pygoscelis papua) Not as many as the Kings, but still thousands. Magellanic Penguin (Spheniscus magellanicus) Only on the Falklands and not nearly as common as the Gentoo. Macaroni Penguin (Eudyptes chrysolophus) Saw a colony at Elsihul Bay on South Georgia. Southern Rockhopper Penguin (Eudyptes chrysocome) A nesting colony among the Black-browed Albatross on West Point Island. Adelie Penguin (Pygoscelis adeliae) Landed near a colony of over 100,000 pairs at Paulet Island on the Peninsula. Chinstrap Penguin (Pygoscelis antarcticus) Seen on the Peninsula and we watched a particularly intense Leopard Seal hunt and kill a Chinstrap. -

![A Report on the Guano-Producing Birds of Peru [“Informe Sobre Aves Guaneras”]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2754/a-report-on-the-guano-producing-birds-of-peru-informe-sobre-aves-guaneras-982754.webp)

A Report on the Guano-Producing Birds of Peru [“Informe Sobre Aves Guaneras”]

PACIFIC COOPERATIVE STUDIES UNIT UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI`I AT MĀNOA Dr. David C. Duffy, Unit Leader Department of Botany 3190 Maile Way, St. John #408 Honolulu, Hawai’i 96822 Technical Report 197 A report on the guano-producing birds of Peru [“Informe sobre Aves Guaneras”] July 2018* *Original manuscript completed1942 William Vogt1 with translation and notes by David Cameron Duffy2 1 Deceased Associate Director of the Division of Science and Education of the Office of the Coordinator in Inter-American Affairs. 2 Director, Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit, Department of Botany, University of Hawai‘i at Manoa Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822, USA PCSU is a cooperative program between the University of Hawai`i and U.S. National Park Service, Cooperative Ecological Studies Unit. Organization Contact Information: Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit, Department of Botany, University of Hawai‘i at Manoa 3190 Maile Way, St. John 408, Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822, USA Recommended Citation: Vogt, W. with translation and notes by D.C. Duffy. 2018. A report on the guano-producing birds of Peru. Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit Technical Report 197. University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Department of Botany. Honolulu, HI. 198 pages. Key words: El Niño, Peruvian Anchoveta (Engraulis ringens), Guanay Cormorant (Phalacrocorax bougainvillii), Peruvian Booby (Sula variegate), Peruvian Pelican (Pelecanus thagus), upwelling, bird ecology behavior nesting and breeding Place key words: Peru Translated from the surviving Spanish text: Vogt, W. 1942. Informe elevado a la Compañia Administradora del Guano par el ornitólogo americano, Señor William Vogt, a la terminación del contracto de tres años que con autorización del Supremo Gobierno celebrara con la Compañia, con el fin de que llevara a cabo estudios relativos a la mejor forma de protección de las aves guaneras y aumento de la produción de las aves guaneras. -

Out-Of-Range Sighting of a South Georgian Diving Petrel Pelecanoides Georgicus in the Southeast Atlantic Ocean

Rollinson et al.: South Georgian Diving Petrel in southeast Atlantic 21 OUT-OF-RANGE SIGHTING OF A SOUTH GEORGIAN DIVING PETREL PELECANOIDES GEORGICUS IN THE SOUTHEAST ATLANTIC OCEAN DOMINIC P. ROLLINSON1, PATRICK CARDWELL2, ANDREW DE BLOCQ1 & JUSTIN R. NICOLAU3 1 Percy FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology, DST/NRF Centre of Excellence, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch, 7701, South Africa ([email protected]) 2 Avian Leisure, Simon’s Town, 7975, South Africa 3 Vorna Valley, Midrand, 1686, South Africa Received 21 August 2016; accepted 29 October 2016 ABSTRACT ROLLINSON, D.P., CARDWELL, P., DE BLOCQ, A. & NICOLAU, J.R. 2017. Out-of-range sighting of a South Georgian Diving Petrel Pelecanoides georgicus in the southeast Atlantic Ocean. Marine Ornithology 45: 21–22. Because of the difficulties of at-sea identification of diving-petrels, little is known about the distribution of Pelecanoides species away from their breeding islands. Here we report an individual that collided with a vessel in the southeast Atlantic Ocean. The species could be confirmed by detailed examination of the bill and nostrils. This record represents a considerable range extension of South Georgian Diving Petrel Pelecanoides georgicus and the farthest from its breeding islands to be confirmed. It suggests that diving-petrels disperse farther from breeding islands than previously known. Key words: vagrant, at-sea identification, breeding islands, South Georgian Diving Petrel On the morning of 25 July 2016, a single South Georgian Diving the nostril openings, as in Common Diving Petrels P. urinatrix Petrel Pelecanoides georgicus was found on one of the upper decks (Harrison 1983). The underside of the bill was broad-based, of the SA Agulhas II. -

SHORT NOTE Re-Laying Following Egg Failure by Common Diving

240 Notornis, 2007, Vol. 54: 240-242 0029-4470 © The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. SHORT NOTE Re-laying following egg failure by common diving petrels (Pelecanoides urinatrix) GRAEME A. TAYLOR Research and Development Group, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 10 420, Wellington 6143, New Zealand [email protected] COLIN M. MISKELLY Wellington Conservancy, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 5086, Wellington 6145, New Zealand The c.130 species of albatrosses and petrels storm petrels (Oceanodroma furcata) where 2nd eggs (Procellariiformes) all lay a single egg during were laid an average of 3 weeks after removal of the each breeding attempt (Marchant & Higgins 1990; 1st egg (from a sample of 36 nests from which eggs Warham 1990). There are few documented instances were removed). In 1 nest, the same female laid a 3rd of members of the order laying a replacement egg egg after the 2nd egg was removed. Both members following egg failure, and all but 1 of these examples of the pair were marked at only 1 of the 29 nests has been from storm petrels (Hydrobatidae). where replacement eggs were laid so the parentage Boersma et al. (1980) reported 29 nests of fork-tailed of the replacement egg could not be confirmed, but at least 1 of the mates remained the same at a further 11 nests. Other examples of storm petrels apparently Received 8 July 2006; accepted 31 August 2006 re-laying following egg failure include: British storm Short Note 241 petrel (Hydrobates pelagicus), n = 2 (Gordon 1931; western coast of Auckland, North I, New Zealand, David 1957); Leach’s storm petrel (O. -

Comparative Seabird Diving Physiology: First Measures of Haematological Parameters and Oxygen Stores in Three New Zealand Procellariiformes

Vol. 523: 187–198, 2015 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published March 16 doi: 10.3354/meps11195 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Comparative seabird diving physiology: first measures of haematological parameters and oxygen stores in three New Zealand Procellariiformes B. J. Dunphy1,*, G. A. Taylor2, T. J. Landers3, R. L . Sagar1, B. L. Chilvers2, L. Ranjard4, M. J. Rayner1,5 1School of Biological Sciences, The University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland 1142, New Zealand 2Department of Conservation, PO Box 10420, Wellington 6143, New Zealand 3Auckland Council, Research, Investigations and Monitoring Unit, Level 4, 1 The Strand, Takapuna Auckland 0622, New Zealand 4The Bioinformatics Institute, The University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland 1142, New Zealand 5Auckland Museum, Private Bag 92018, Victoria Street West, Auckland 1142, New Zealand ABSTRACT: Within breath-hold diving endotherms, procellariiform seabirds present an intriguing anomaly as they regularly dive to depths not predicted by allometric models. How this is achieved is not known as even basic measures of physiological diving capacity have not been undertaken in this group. To remedy this we combined time depth recorder (TDR) measurements of dive behaviour with haematology and oxygen store estimates for 3 procellariiform species (common diving petrels Pelecanoides urinatrix urinatrix; grey-faced petrels Pterodroma macro ptera gouldi; and sooty shearwaters Puffinus griseus) during their incubation phase. Among species, we found distinct differences in dive depth (average and maximal), dive duration and dives h−1, with sooty shearwaters diving deeper and for longer than grey-faced petrels and common diving petrels. Conversely, common diving petrels dove much more frequently, albeit to shallow depths, whereas grey-faced petrels rarely dived whatsoever. -

Flora and Fauna of Wooded Island, Inner Hauraki Gulf, by G.A. Taylor

Tane 37: 91-98 (1999) FLORA AND FAUNA OF WOODED ISLAND, INNER HAURAKI GULF G.A. Taylor1 and A.J.D. Tennyson2 '50 Kinghorne Street, Strathmore, Wellington, 21 Lincoln Street, Brooklyn, Wellington SUMMARY Wooded Island has a vascular flora of 33 species of which 70% are native. The island is covered mainly in a low forest of taupata (Coprosma repens), coastal mahoe (Melicytus novae-zelandiae) and boxthorn (Lycium ferocissimum). There are significant colonies of common diving petrels (Pelecanoides urinatrix) and fluttering shearwaters (Puffinus gavia). Blue penguins (Eudyptula minor) and white-fronted terns (Sterna striata) also breed on the island. Eradication of boxthorn is recommended, as it is having an impact on the survival of the seabirds. Keywords: Pelecanoides urinatrix; Puffinus gavia; vascular flora; Wooded Island; New Zealand INTRODUCTION Wooded Island (0.95 ha) lies 200 m off the northern coast of Tiritiri Matangi Island, inner Hauraki Gulf (Lat 36° 35'S, Long 174° 53'E) (Fig. 1). Fig. 1. Wooded Island from Tiritiri Matangi Island, August 1987. Photo: G.A. Taylor. 91 The island is sometimes known as Little Tiri Island. Two visits were made to Wooded Island by the authors. On 29 August 1987, GAT, Tim Lovegrove and John Dowding landed at 0945 h and spent about two hours ashore. Two adjacent rock stacks were also surveyed on this visit. On 1 February 1989, GAT, AJDT and Gill Eller landed between 1200-1500 h on the main island and also checked the north-western rock stack. During our landings, we compiled a list of all vascular plant species, seabirds were surveyed, landbirds noted and searches made for reptiles. -

Maximum Dive Depths of Eight New Zealand Procellariiformes, Including Pterodroma Species

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, Volume 142(1), 2008 89 MAXIMUM DIVE DEPTHS OF EIGHT NEW ZEALAND PROCELLARIIFORMES, INCLUDING PTERODROMA SPECIES by G. A. Taylor (with four text-figures, one plate and one table) Taylor, G.A. 2008 (31 :x): Maximum dive depths of eight New Zealand Procellariiformes, including Pterodroma species. Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 142(1): 89-98. https://doi.org/10.26749/rstpp.142.1.89 ISSN 0080-4703. Research & Development Group, Dep::trtment of Conservation, PO Box 10420, Wellington, New Zealand. Email: [email protected] Lightweight capillary tube depth gauges were attached to eight petrel species breeding at New Zealand colonies during the period 1998-2008. This paper presents the first information on the diving ability of Pterodroma petrels. Grey-faced Petrels, Pterodroma macroptera gouldi, re corded maximum dives down to 23 m. Males (6.3 ± 6.3 m SD) dived deeper on average than females (3.6 ± 2.5 m) during the incubation period but not significantlyso (P�0.06). Breeding birds dived significantlydeeper on average than non-breeders, and breeding males dived significantly deeper on average than non-breeding males. The two small Pterodroma species sampled, Pterodroma pycrofti and Pterodroma nigripennis, only exhibited shallow dives down to 2 m but sample sizes were small. Sooty Shearwaters, Pujfinus griseus, had mean maximum dive depths of 42.7 ± 23.7 m, with males (53.0 ± 17.3 m) diving significantly deeper on average than females (20.1 ± 20.4 m) during the incubation period. One male Sooty Shearwarer dived to nearly 93 m, the deepest dive so far recorded in the order Procellariiformes. -

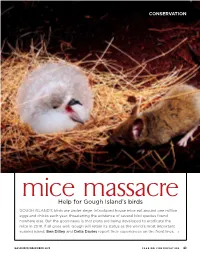

Help for Gough Island's Birds

conservation > mice massacre Help for Gough Island’s birds GOUGh Island’s birds are under siege. Introduced house mice eat around one million eggs and chicks each year, threatening the existence of several bird species found nowhere else. But the good news is that plans are being developed to eradicate the mice in 2019. If all goes well, Gough will retain its status as the world’s most important seabird island. Ben Dilley and Delia Davies report their experiences on the front lines. > NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2015 SEABIRD CONSERVATION 43 GOUGH ISLAND is spectacular: musculus, they triggered an eco 65 square kilometres of rugged logical disaster that only now can south africa volcanic mountains and precip we attempt to rectify. itous valleys rising sheer from the Cape Town sea. It lies on the edge of the Roar irds that live on oceanic ing Forties in the South Atlantic, islands have evolved in Tristan da Cunha midway between South Africa and the absence of landbased Gough Island Argentina, and is administered by predators,B because most terrest rial Tristan da Cunha, a UK Overseas animals were unable to colon ise Territory. Often regarded as the these remote specks of land. When SOUTH ATLANTIC OCEAN Marion Island world’s most important seabird humans reached these islands, breeding island, Gough supports they often introduced predators literally millions of seabirds of 23 such as cats, rats and even snakes, species, three of which breed al with cata strophic impacts. Unable in 2004 by Ross Wanless and An most exclusively on Gough: the to appreciate the danger posed by drea Angel, who also filmed mice Tristan Albatross, Atlantic Pet these strange new arrivals, island killing chicks of Atlantic Petrels rel and Macgillivray’s Prion (see birds were easy prey. -

ECOLOGY, TAXONOMIC STATUS, and CONSERVATION of the SOUTH GEORGIAN DIVING PETREL (Pelecanoides Georgicus) in NEW ZEALAND

ECOLOGY, TAXONOMIC STATUS, AND CONSERVATION OF THE SOUTH GEORGIAN DIVING PETREL (Pelecanoides georgicus) IN NEW ZEALAND BY JOHANNES HARTMUT FISCHER A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Conservation Biology School of Biological Sciences Faculty of Sciences Victoria University of Wellington September 2016 Supervisor: Dr. Heiko U. Wittmer, Senior Lecturer at the School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington. © Johannes Hartmut Fischer. September 2016. Ecology, Taxonomic Status and Conservation of the South Georgian Diving Petrel (Pelecanoides georgicus) in New Zealand. ABSTRACT ROCELLARIFORMES IS A diverse order of seabirds under considerable pressure P from onshore and offshore threats. New Zealand hosts a large and diverse community of Procellariiformes, but many species are at risk of extinction. In this thesis, I aim to provide an overview of threats and conservation actions of New Zealand’s Procellariiformes in general, and an assessment of the remaining terrestrial threats to the South Georgian Diving Petrel (Pelecanoides georgicus; SGDP), a Nationally Critical Procellariiform species restricted to Codfish Island (Whenua Hou), post invasive species eradication efforts in particular. I reviewed 145 references and assessed 14 current threats and 13 conservation actions of New Zealand’s Procellariiformes (n = 48) in a meta-analysis. I then assessed the terrestrial threats to the SGDP by analysing the influence of five physical, three competition, and three plant variables on nest-site selection using an information theoretic approach. Furthermore, I assessed the impacts of interspecific interactions at 20 SGDP burrows using remote cameras. Finally, to address species limits within the SGDP complex, I measured phenotypic differences (10 biometric and eight plumage characters) in 80 live birds and 53 study skins, as conservation prioritisation relies on accurate taxonomic classification.