P0131-P0146.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seabird Year-Round and Historical Feeding Ecology: Blood and Feather Δ13c and Δ15n Values Document Foraging Plasticity of Small Sympatric Petrels

Vol. 505: 267–280, 2014 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published May 28 doi: 10.3354/meps10795 Mar Ecol Prog Ser FREEREE ACCESSCCESS Seabird year-round and historical feeding ecology: blood and feather δ13C and δ15N values document foraging plasticity of small sympatric petrels Yves Cherel1,*, Maëlle Connan1, Audrey Jaeger1, Pierre Richard2 1Centre d’Etudes Biologiques de Chizé, UMR 7372 du CNRS et de l’Université de La Rochelle, BP 14, 79360 Villiers-en-Bois, France 2Laboratoire Littoral, Environnement et Sociétés, UMR 7266 du CNRS et de l’Université de La Rochelle, 2 rue Olympe de Gouges, 17000 La Rochelle, France ABSTRACT: The foraging ecology of small seabirds remains poorly understood because of the dif- ficulty of studying them at sea. Here, the extent to which 3 sympatric seabirds (blue petrel, thin- billed prion and common diving petrel) alter their foraging ecology across the annual cycle was investigated using stable isotopes. δ13C and δ15N values were used as proxies of the birds’ foraging habitat and diet, respectively, and were measured in 3 tissues (plasma, blood cells and feathers) that record trophic information at different time scales. Long-term temporal changes were inves- tigated by measuring feather isotopic values from museum specimens. The study was conducted at the subantarctic Kerguelen Islands and emphasizes 4 main features. (1) The 3 species highlight a strong connection between subantarctic and Antarctic pelagic ecosystems, because they all for- aged in Antarctic waters at some stages of the annual cycle. (2) Foraging niches are stage- dependent, with petrels shifting their feeding grounds during reproduction either from oceanic to productive coastal waters (common diving petrel) or from subantarctic to high-Antarctic waters where they fed primarily on crustaceans (blue petrel and thin-billed prion). -

Population Estimates and Temporal Trends of Pribilof Island Seabirds

POPULATION ESTIMATES AND TEMPORAL TRENDS OF PRIBILOF ISLAND SEABIRDS by F. Lance Craighead and Jill Oppenheim Alaska Biological Research P.O. BOX 81934 Fairbanks, Alaska 99708 Final Report Outer Continental Shelf Environmental Assessment Program Research Unit 628 November 1982 307 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Dan Roby and Karen Brink, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, were especially helpful to us during our stay on St. George and shared their observations with us. Bob Day, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, also provided comparative data from his findings on St. George in 1981. We would like to thank the Aleut communities of St. George and St. Paul and Roger Gentry and other NMFS biologists on St. George for their hospitality and friendship. Bob Ritchie and Jim Curatolo edited an earlier version of this report. Mary Moran drafted the figures. Nancy Murphy and Patty Dwyer-Smith typed drafts of this report. Amy Reges assisted with final report preparation. Finally, we’d like to thank Dr. J.J. Hickey for initiating seabird surveys on the Pribi of Islands, which were the basis for this study. This study was funded by the Bureau of Land Management through interagency agreement with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administra- tion, as part of the Outer Continental Shelf Environmental Assessment Program. 308 TABLE OF CONTENTS ~ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. ● . ● . ● . ● . 308 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . ✎ . ● ✎ . ● . ● ● . ✎ . ● ● . 311 INTRODUCTION. ✎ . ● ✎ . ✎ . ✎ ✎ . ● ✎ ● . ● ✎ . 313 STUDY AREA. ● . ✎ ✎ . ✎ . ✎ ✎ . ✎ ✎ ✎ . , . ● ✎ . ● . 315 METHODS . ● . ✎ -

Species List

Antarctica Trip Report November 30 – December 18, 2017 | Compiled by Greg Smith With Greg Smith, guide, and participants Anne, Karen, Anita, Alberto, Dick, Patty & Andy, and Judy & Jerry Bird List — 78 Species Seen Anatidae: Ducks, Geese, and Swans (8) Upland Goose (Chloephaga picta) Only seen on the Falklands, and most had young or were on nests. Kelp Goose (Chloephaga hybrid) On the beach (or close to the beach) at West Point and Carcass Islands. Ruddy-headed Goose (Chloephaga rubidiceps) Mixed in with the grazing Upland Geese on the Falklands. Flightless Steamer Duck (Tachyeres pteneres) Found on both islands that we visited, and on Stanley. Crested Duck (Lophonetta specularioides) Not common at all with only a few seen in a pond on Carcass Island. Yellow-billed (Speckled) Teal (Anas flavirostris) Two small flocks were using freshwater ponds. Yellow-billed Pintail (Anas georgica) Fairly common on South Georgia. South Georgia Pintail (Anas georgica georgica) Only on South Georgia and seen on every beach access. Spheniscidae: Penguins (7) King Penguin (Aptenodytes patagonicus) Only on South Georgia and there were thousands and thousands. Gentoo Penguin (Pygoscelis papua) Not as many as the Kings, but still thousands. Magellanic Penguin (Spheniscus magellanicus) Only on the Falklands and not nearly as common as the Gentoo. Macaroni Penguin (Eudyptes chrysolophus) Saw a colony at Elsihul Bay on South Georgia. Southern Rockhopper Penguin (Eudyptes chrysocome) A nesting colony among the Black-browed Albatross on West Point Island. Adelie Penguin (Pygoscelis adeliae) Landed near a colony of over 100,000 pairs at Paulet Island on the Peninsula. Chinstrap Penguin (Pygoscelis antarcticus) Seen on the Peninsula and we watched a particularly intense Leopard Seal hunt and kill a Chinstrap. -

Foraging Radii and Energetics of Least Auklets (Aethia Pusilla) Breeding on Three Bering Sea Islands

647 Foraging Radii and Energetics of Least Auklets (Aethia pusilla) Breeding on Three Bering Sea Islands Bryan S. Obst1·* Robert W. Russell2·t 2 George L. Hunt, Jr. ·; Zoe A. Eppler·§ Nancy M. Harrison2·ll 1Departmem of Biology, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90024; 2Depanment of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Irvine, California 92717 Accepted 11/18/94 Abstract We studied the relationship between the foraging radius and energy economy of least auklets (Aethia pusilla) breeding in colonies on three islands in the Bering Sea (St. Lawrence, St. Matthew, and St. George Islands). The distan:ce to which auklets commuted on foraging trips varied by more than an order of magnitude (5-56 km), but mean field metabolic rate (FMR) did not vary significantly among birds from the three islands. These observations indicate that allocation to various compartments of time and energy budgets is flexible and suggest that least auklets may have a preferred level ofdaily energy expenditure that is simi lar across colonies. We modeled the partitioning of energy to various activities and hypothesize that the added cost of commuting incurred by auktets from St. Lawrence Island (foraging radius, 56 km) was offiet by reduced energy costs while foraging at sea. Data on bird diets and prey abundances indicated that aukletsfrom St. Lawrence Island fed on larger, more energy-rich copepods than did aukletsfrom St. Matthew island (foraging radius, 5 km) but that depth-aver aged prey density did not differ significantly between the birds' principal forag ing areas. However, previous studies have indicated that zooplankton abun dance is vertically compressed into near-surface layers in stratified waters off St. -

Out-Of-Range Sighting of a South Georgian Diving Petrel Pelecanoides Georgicus in the Southeast Atlantic Ocean

Rollinson et al.: South Georgian Diving Petrel in southeast Atlantic 21 OUT-OF-RANGE SIGHTING OF A SOUTH GEORGIAN DIVING PETREL PELECANOIDES GEORGICUS IN THE SOUTHEAST ATLANTIC OCEAN DOMINIC P. ROLLINSON1, PATRICK CARDWELL2, ANDREW DE BLOCQ1 & JUSTIN R. NICOLAU3 1 Percy FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology, DST/NRF Centre of Excellence, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch, 7701, South Africa ([email protected]) 2 Avian Leisure, Simon’s Town, 7975, South Africa 3 Vorna Valley, Midrand, 1686, South Africa Received 21 August 2016; accepted 29 October 2016 ABSTRACT ROLLINSON, D.P., CARDWELL, P., DE BLOCQ, A. & NICOLAU, J.R. 2017. Out-of-range sighting of a South Georgian Diving Petrel Pelecanoides georgicus in the southeast Atlantic Ocean. Marine Ornithology 45: 21–22. Because of the difficulties of at-sea identification of diving-petrels, little is known about the distribution of Pelecanoides species away from their breeding islands. Here we report an individual that collided with a vessel in the southeast Atlantic Ocean. The species could be confirmed by detailed examination of the bill and nostrils. This record represents a considerable range extension of South Georgian Diving Petrel Pelecanoides georgicus and the farthest from its breeding islands to be confirmed. It suggests that diving-petrels disperse farther from breeding islands than previously known. Key words: vagrant, at-sea identification, breeding islands, South Georgian Diving Petrel On the morning of 25 July 2016, a single South Georgian Diving the nostril openings, as in Common Diving Petrels P. urinatrix Petrel Pelecanoides georgicus was found on one of the upper decks (Harrison 1983). The underside of the bill was broad-based, of the SA Agulhas II. -

SHORT NOTE Re-Laying Following Egg Failure by Common Diving

240 Notornis, 2007, Vol. 54: 240-242 0029-4470 © The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. SHORT NOTE Re-laying following egg failure by common diving petrels (Pelecanoides urinatrix) GRAEME A. TAYLOR Research and Development Group, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 10 420, Wellington 6143, New Zealand [email protected] COLIN M. MISKELLY Wellington Conservancy, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 5086, Wellington 6145, New Zealand The c.130 species of albatrosses and petrels storm petrels (Oceanodroma furcata) where 2nd eggs (Procellariiformes) all lay a single egg during were laid an average of 3 weeks after removal of the each breeding attempt (Marchant & Higgins 1990; 1st egg (from a sample of 36 nests from which eggs Warham 1990). There are few documented instances were removed). In 1 nest, the same female laid a 3rd of members of the order laying a replacement egg egg after the 2nd egg was removed. Both members following egg failure, and all but 1 of these examples of the pair were marked at only 1 of the 29 nests has been from storm petrels (Hydrobatidae). where replacement eggs were laid so the parentage Boersma et al. (1980) reported 29 nests of fork-tailed of the replacement egg could not be confirmed, but at least 1 of the mates remained the same at a further 11 nests. Other examples of storm petrels apparently Received 8 July 2006; accepted 31 August 2006 re-laying following egg failure include: British storm Short Note 241 petrel (Hydrobates pelagicus), n = 2 (Gordon 1931; western coast of Auckland, North I, New Zealand, David 1957); Leach’s storm petrel (O. -

Comparative Seabird Diving Physiology: First Measures of Haematological Parameters and Oxygen Stores in Three New Zealand Procellariiformes

Vol. 523: 187–198, 2015 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published March 16 doi: 10.3354/meps11195 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Comparative seabird diving physiology: first measures of haematological parameters and oxygen stores in three New Zealand Procellariiformes B. J. Dunphy1,*, G. A. Taylor2, T. J. Landers3, R. L . Sagar1, B. L. Chilvers2, L. Ranjard4, M. J. Rayner1,5 1School of Biological Sciences, The University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland 1142, New Zealand 2Department of Conservation, PO Box 10420, Wellington 6143, New Zealand 3Auckland Council, Research, Investigations and Monitoring Unit, Level 4, 1 The Strand, Takapuna Auckland 0622, New Zealand 4The Bioinformatics Institute, The University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland 1142, New Zealand 5Auckland Museum, Private Bag 92018, Victoria Street West, Auckland 1142, New Zealand ABSTRACT: Within breath-hold diving endotherms, procellariiform seabirds present an intriguing anomaly as they regularly dive to depths not predicted by allometric models. How this is achieved is not known as even basic measures of physiological diving capacity have not been undertaken in this group. To remedy this we combined time depth recorder (TDR) measurements of dive behaviour with haematology and oxygen store estimates for 3 procellariiform species (common diving petrels Pelecanoides urinatrix urinatrix; grey-faced petrels Pterodroma macro ptera gouldi; and sooty shearwaters Puffinus griseus) during their incubation phase. Among species, we found distinct differences in dive depth (average and maximal), dive duration and dives h−1, with sooty shearwaters diving deeper and for longer than grey-faced petrels and common diving petrels. Conversely, common diving petrels dove much more frequently, albeit to shallow depths, whereas grey-faced petrels rarely dived whatsoever. -

SYN Seabird Curricul

Seabirds 2017 Pribilof School District Auk Ecological Oregon State Seabird Youth Network Pribilof School District Ram Papish Consulting University National Park Service Thalassa US Fish and Wildlife Service Oikonos NORTAC PB i www.seabirdyouth.org Elementary/Middle School Curriculum Table of Contents INTRODUCTION . 1 CURRICULUM OVERVIEW . 3 LESSON ONE Seabird Basics . 6 Activity 1.1 Seabird Characteristics . 12 Activity 1.2 Seabird Groups . 20 Activity 1.3 Seabirds of the Pribilofs . 24 Activity 1.4 Seabird Fact Sheet . 26 LESSON TWO Seabird Feeding . 31 Worksheet 2.1 Seabird Feeding . 40 Worksheet 2.2 Catching Food . 42 Worksheet 2.3 Chick Feeding . 44 Worksheet 2.4 Puffin Chick Feeding . 46 LESSON THREE Seabird Breeding . 50 Worksheet 3.1 Seabird Nesting Habitats . .5 . 9 LESSON FOUR Seabird Conservation . 63 Worksheet 4.1 Rat Maze . 72 Worksheet 4.2 Northern Fulmar Threats . 74 Worksheet 4.3 Northern Fulmars and Bycatch . 76 Worksheet 4.4 Northern Fulmars Habitat and Fishing . 78 LESSON FIVE Seabird Cultural Importance . 80 Activity 5.1 Seabird Cultural Importance . 87 LESSON SIX Seabird Research Tools and Methods . 88 Activity 6.1 Seabird Measuring . 102 Activity 6.2 Seabird Monitoring . 108 LESSON SEVEN Seabirds as Marine Indicators . 113 APPENDIX I Glossary . 119 APPENDIX II Educational Standards . 121 APPENDIX III Resources . 123 APPENDIX IV Science Fair Project Ideas . 130 ii www.seabirdyouth.org 1 INTRODUCTION 2017 Seabirds SEABIRDS A seabird is a bird that spends most of its life at sea. Despite a diversity of species, seabirds share similar characteristics. They are all adapted for a life at sea and they all must come to land to lay their eggs and raise their chicks. -

Flora and Fauna of Wooded Island, Inner Hauraki Gulf, by G.A. Taylor

Tane 37: 91-98 (1999) FLORA AND FAUNA OF WOODED ISLAND, INNER HAURAKI GULF G.A. Taylor1 and A.J.D. Tennyson2 '50 Kinghorne Street, Strathmore, Wellington, 21 Lincoln Street, Brooklyn, Wellington SUMMARY Wooded Island has a vascular flora of 33 species of which 70% are native. The island is covered mainly in a low forest of taupata (Coprosma repens), coastal mahoe (Melicytus novae-zelandiae) and boxthorn (Lycium ferocissimum). There are significant colonies of common diving petrels (Pelecanoides urinatrix) and fluttering shearwaters (Puffinus gavia). Blue penguins (Eudyptula minor) and white-fronted terns (Sterna striata) also breed on the island. Eradication of boxthorn is recommended, as it is having an impact on the survival of the seabirds. Keywords: Pelecanoides urinatrix; Puffinus gavia; vascular flora; Wooded Island; New Zealand INTRODUCTION Wooded Island (0.95 ha) lies 200 m off the northern coast of Tiritiri Matangi Island, inner Hauraki Gulf (Lat 36° 35'S, Long 174° 53'E) (Fig. 1). Fig. 1. Wooded Island from Tiritiri Matangi Island, August 1987. Photo: G.A. Taylor. 91 The island is sometimes known as Little Tiri Island. Two visits were made to Wooded Island by the authors. On 29 August 1987, GAT, Tim Lovegrove and John Dowding landed at 0945 h and spent about two hours ashore. Two adjacent rock stacks were also surveyed on this visit. On 1 February 1989, GAT, AJDT and Gill Eller landed between 1200-1500 h on the main island and also checked the north-western rock stack. During our landings, we compiled a list of all vascular plant species, seabirds were surveyed, landbirds noted and searches made for reptiles. -

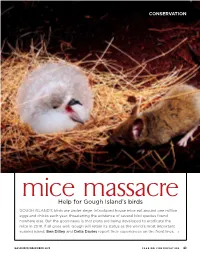

Help for Gough Island's Birds

conservation > mice massacre Help for Gough Island’s birds GOUGh Island’s birds are under siege. Introduced house mice eat around one million eggs and chicks each year, threatening the existence of several bird species found nowhere else. But the good news is that plans are being developed to eradicate the mice in 2019. If all goes well, Gough will retain its status as the world’s most important seabird island. Ben Dilley and Delia Davies report their experiences on the front lines. > NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2015 SEABIRD CONSERVATION 43 GOUGH ISLAND is spectacular: musculus, they triggered an eco 65 square kilometres of rugged logical disaster that only now can south africa volcanic mountains and precip we attempt to rectify. itous valleys rising sheer from the Cape Town sea. It lies on the edge of the Roar irds that live on oceanic ing Forties in the South Atlantic, islands have evolved in Tristan da Cunha midway between South Africa and the absence of landbased Gough Island Argentina, and is administered by predators,B because most terrest rial Tristan da Cunha, a UK Overseas animals were unable to colon ise Territory. Often regarded as the these remote specks of land. When SOUTH ATLANTIC OCEAN Marion Island world’s most important seabird humans reached these islands, breeding island, Gough supports they often introduced predators literally millions of seabirds of 23 such as cats, rats and even snakes, species, three of which breed al with cata strophic impacts. Unable in 2004 by Ross Wanless and An most exclusively on Gough: the to appreciate the danger posed by drea Angel, who also filmed mice Tristan Albatross, Atlantic Pet these strange new arrivals, island killing chicks of Atlantic Petrels rel and Macgillivray’s Prion (see birds were easy prey. -

Comparative Reproductive Ecology of the Auks (Family Alcidae) with Emphasis on the Marbled Murrelet

Chapter 3 Comparative Reproductive Ecology of the Auks (Family Alcidae) with Emphasis on the Marbled Murrelet Toni L. De Santo1, 2 S. Kim Nelson1 Abstract: Marbled Murrelets (Brachyramphus marmoratus) are breed on the Farallon Islands in the Pacific Ocean (Common comparable to most alcids with respect to many features of their Murre, Pigeon Guillemot, Cassin’s Auklet, Rhinoceros Auklet, reproductive ecology. Most of the 22 species of alcids are colonial and Tufted Puffin) are presented by Ainley (1990), Ainley in their nesting habits, most exhibit breeding site, nest site, and and others (1990a, b, c) and Boekelheide and others (1990). mate fidelity, over half lay one egg clutches, and all share duties Four inshore fish feeding alcids of the northern Pacific Ocean of incubation and chick rearing with their mates. Most alcids nest on rocky substrates, in earthen burrows, or in holes in sand, (Kittlitz’s Murrelet, Pigeon Guillemot, Spectacled Guillemot, around logs, or roots. Marbled Murrelets are unique in choice of and Marbled Murrelet) are reviewed by Ewins and others nesting habitat. In the northern part of their range, they nest on (1993) (also see Marshall 1988a for a review of the Marbled rocky substrate; elsewhere, they nest in the upper canopy of coastal Murrelet). The Ancient Murrelet, another inhabitant of the coniferous forest trees, sometimes in what appear to be loose northern Pacific Ocean, has been reviewed by Gaston (1992). aggregations. Marbled Murrelet young are semi-precocial as are Alcids that nest in small, loosely-aggregated colonies, as most alcids, yet they hatch from relatively large eggs (relative to isolated pairs, or in areas less accessible to researchers, have adult body size) which are nearly as large as those of the precocial not been well studied. -

ECOLOGY, TAXONOMIC STATUS, and CONSERVATION of the SOUTH GEORGIAN DIVING PETREL (Pelecanoides Georgicus) in NEW ZEALAND

ECOLOGY, TAXONOMIC STATUS, AND CONSERVATION OF THE SOUTH GEORGIAN DIVING PETREL (Pelecanoides georgicus) IN NEW ZEALAND BY JOHANNES HARTMUT FISCHER A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Conservation Biology School of Biological Sciences Faculty of Sciences Victoria University of Wellington September 2016 Supervisor: Dr. Heiko U. Wittmer, Senior Lecturer at the School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington. © Johannes Hartmut Fischer. September 2016. Ecology, Taxonomic Status and Conservation of the South Georgian Diving Petrel (Pelecanoides georgicus) in New Zealand. ABSTRACT ROCELLARIFORMES IS A diverse order of seabirds under considerable pressure P from onshore and offshore threats. New Zealand hosts a large and diverse community of Procellariiformes, but many species are at risk of extinction. In this thesis, I aim to provide an overview of threats and conservation actions of New Zealand’s Procellariiformes in general, and an assessment of the remaining terrestrial threats to the South Georgian Diving Petrel (Pelecanoides georgicus; SGDP), a Nationally Critical Procellariiform species restricted to Codfish Island (Whenua Hou), post invasive species eradication efforts in particular. I reviewed 145 references and assessed 14 current threats and 13 conservation actions of New Zealand’s Procellariiformes (n = 48) in a meta-analysis. I then assessed the terrestrial threats to the SGDP by analysing the influence of five physical, three competition, and three plant variables on nest-site selection using an information theoretic approach. Furthermore, I assessed the impacts of interspecific interactions at 20 SGDP burrows using remote cameras. Finally, to address species limits within the SGDP complex, I measured phenotypic differences (10 biometric and eight plumage characters) in 80 live birds and 53 study skins, as conservation prioritisation relies on accurate taxonomic classification.