Textiles, Community and DIY in Post-Industrial Hamilton Jen Anisef

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPECIAL GENERAL ISSUES COMMITTEE LIGHT RAIL TRANSIT (LRT) MINUTES 16-026 10:30 A.M

SPECIAL GENERAL ISSUES COMMITTEE LIGHT RAIL TRANSIT (LRT) MINUTES 16-026 10:30 a.m. Tuesday, October 25, 2016 Council Chambers Hamilton City Hall 71 Main Street West ______________________________________________________________________ Present: Mayor F. Eisenberger, Deputy Mayor D. Skelly (Chair) Councillors T. Whitehead, T. Jackson, C. Collins, S. Merulla, M. Green, J. Farr, A. Johnson, D. Conley, M. Pearson, B. Johnson, L. Ferguson, R. Pasuta, J. Partridge Absent with Regrets: Councillor A. VanderBeek – Personal _____________________________________________________________________ THE FOLLOWING ITEMS WERE REFERRED TO COUNCIL FOR CONSIDERATION: 1. Light Rail Transit (LRT) Project Update (PED16199) (City Wide) (Item 5.1) (Conley/Pearson) That Report PED16199, respecting the Light Rail Transit (LRT) Project Update, be received. CARRIED 2. Hamilton Street Railway (HSR) Fare Integration (PW16066) (City Wide) (Item 6.1) (Eisenberger/Ferguson) That Report PW16066, respecting Hamilton Street Railway (HSR) Fare Integration, be received. CARRIED 3. Possibility of adding the LRT A-Line at the same time as building the B- Line (7.2) (Merulla/Whitehead) That staff be directed to communicate with Metrolinx to determine the possibility of adding the LRT A-Line at the same time as building the B-Line and report back to the LRT Sub-Committee. CARRIED General Issues Committee October 25, 2016 Minutes 16-026 Page 2 of 26 4. LRT Project Not to Negatively Affect Hamilton’s Allocation of Provincial Gas Tax Revenue or Future Federal Infrastructure Public Transit Funding (Item 7.3) (Collins/Merulla) That the Province of Ontario be requested to commit that the Hamilton Light Rail Transit (LRT) Project will not negatively affect Hamilton’s allocation of Provincial Gas Tax Funding or Future Federal Infrastructure Public Transit Funding. -

It's Happeninghere

HAMILTON IT’S HAPPENING HERE Hamilton’s own Arkells perform at the 2014 James Street Supercrawl – photo credit: Colette Schotsman www.tourismhamilton.com HAMILTON: A SNAPSHOT Rich in culture and history and surrounded by spectacular nature, Hamilton is a city like no other. Unique for its ideal blend of urban and natural offerings, this post-industrial, ambitious city is in the midst of a fascinating transformation and brimming with story ideas. Ideally located in the heart of southern Ontario, midway between Toronto and Niagara Falls, Hamilton provides an ideal destination or detour. From its vibrant arts scene, to its rich heritage and history, to its incredible natural beauty, it’s happening here. Where Where Where THE ARTS NATURE HISTORY thrive surrounds is revealed Hamilton continues to make Bounded by the picturesque shores One of the oldest and most headlines for its explosive arts scene of Lake Ontario and the lush historically fascinating cities in the – including a unique grassroots landscape of the Niagara region outside of Toronto, Hamilton movement evolving alongside the Escarpment, Hamilton offers a is home to heritage-rich architecture, city’s long-established arts natural playground for outdoor lovers world-class museums and 15 institutions. Inspiring, fun and – all within minutes of the city’s core. National Historic Sites. accessible, the arts in Hamilton are yours to explore. • More than 100 waterfalls can be • Dundurn Castle brings Hamilton’s found just off the Bruce Trail along Victorian era to life in a beautifully • Monthly James Street North the Niagara Escarpment, a restored property overlooking the Art Crawls and the annual James UNESCO World Biosphere Reserve harbour while Hamilton Museum of Street Supercrawl draw hundreds of that cuts across the city. -

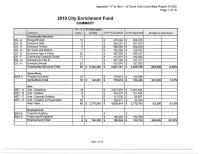

2019 City Enrichment Fund SUMMARY

Appendix "A" to Item 1 of Grant Sub-Committee Report 19-002 Page 1 of 19 2019 City Enrichment Fund SUMMARY No. of 2019 Bu get Category Apps 2019 Requested 2019 Approved Budget vs Approved Community Services CS-A Hunger/Shelter 10 $ 416,324 $ 368,015 CS-B Everyone Safe 9 $ 294,291 $ 287,903 CS-C Everyone Thri es 9 $ 299,588 $ 269,256 CS-D No Youth Left Behind 7 $ 180,209 $ 159,702 CS-E Everyone Age in Place 20 $ 485,352 $ 455,101 CS-F Community Capacity Grows 11 $ 214,373 $ 190,492 CS-G Someone to Talk to 7 $ 247,728 $ 141,317 CS-H Emerging Needs 22 $ 553,916 $ 357,383 Community Services Total 95 $ 2,164,360 $ 2,691,781 $ 2,229,169 -$64,809 -2.99% Agriculture AGRA Program & E ents 18 $ 178,615 $ 133,356 Agriculture Total 18 $ 143,361 $ 178,615 $ 133,356 $10,005 7.67% Arts ART-A Arts - Operating 34 $ 3,977,467 $ 2,437,364 ART-B Arts - Festival 10 $ 300,070 $ 181,486 ART-C Arts - Capacity Building 9 $ 113,000 $ 58,597 ART-D Arts - Creation & Presentation 35 $ 238,877 $ 96,295 Arts Total . -s - 88 $ 2,770,542 $ 4,629,414 $ 2,773,742 -$3,200 -0.12% Environment ENV-A Capacity Building - $ - $ - ENV-C Project and Programs 8 $ 180,364 $ 120,764 Environment Total 8 $ 146,390 $ 180,364 $ 120,764 $25,626 22.30% Page 1 of 19 Appendix "A" to Item 1 of Grant Sub-Committee Report 19-002 Page 2 of 19 No. -

Hamilton Harbour and Watershed Fisheries Management Plan

Hamilton Harbour and Watershed Fisheries Management Plan A cooperative resource management plan developed by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and the Royal Botanical Gardens April 7, 2010 Correct citation for this publication: Bowlby, J.N. , K. McCormack, and M.G. Heaton. 2010. Hamilton Harbour and Watershed Fisheries Management Plan. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Royal Botanical Gardens. Hamilton Harbour and Watershed Fisheries Management Plan Executive Summary Introduction The Hamilton Harbour and Watershed Fisheries Management Plan (HHWFMP) provides information about the characteristics of the watershed, the state of fisheries resources, and guidance for the management of fisheries resources in the watershed. The need for the HHWFMP developed directly from successes of the Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan (RAP) to restore water quality and fish habitat in Hamilton Harbour and its watershed. Hamilton Harbour is a large embayment at the western tip of Lake Ontario. The main tributaries of Hamilton Harbour include Spencer Creek, Grindstone Creek, and Red Hill Creek. The Hamilton Harbour watershed, which includes the contributing streams and creeks, covers an area of approximately 500 km2. It encompasses some of the regions most scenic and diverse landscapes: the Niagara Escarpment is a prominent physical feature, and Cootes Paradise is one of the largest and most significant coastal wetlands of Lake Ontario. Water quality in Hamilton Harbour and Cootes Paradise is the most important factor that currently limits the successful restoration of sustainable, self–reproducing native fish community. In 1987, Hamilton Harbour was officially designated as an Area of Concern (AOC) by the International Joint Commission, pursuant to the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement. -

Randle Reef Sediment Remediation Project

Randle Reef Sediment Remediation Project Comprehensive Study Report Prepared for: Environment Canada Fisheries and Oceans Canada Transport Canada Hamilton Port Authority Prepared by: The Randle Reef Sediment Remediation Project Technical Task Group AECOM October 30, 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Randle Reef Sediment Remediation Project Technical Task Group Members: Roger Santiago, Environment Canada Erin Hartman, Environment Canada Rupert Joyner, Environment Canada Sue-Jin An, Environment Canada Matt Graham, Environment Canada Cheriene Vieira, Ontario Ministry of Environment Ron Hewitt, Public Works and Government Services Canada Bill Fitzgerald, Hamilton Port Authority The Technical Task Group gratefully acknowledges the contributions of the following parties in the preparation and completion of this document: Environment Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Transport Canada, Hamilton Port Authority, Health Canada, Public Works and Government Services Canada, Ontario Ministry of Environment, Canadian Environmental Assessment Act Agency, D.C. Damman and Associates, City of Hamilton, U.S. Steel Canada, National Water Research Institute, AECOM, ARCADIS, Acres & Associated Environmental Limited, Headwater Environmental Services Corporation, Project Advisory Group, Project Implementation Team, Bay Area Restoration Council, Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan Office, Hamilton Conservation Authority, Royal Botanical Gardens and Halton Region Conservation Authority. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................. -

General Issues Committee Agenda Package

City of Hamilton GENERAL ISSUES COMMITTEE REVISED Meeting #: 19-004 Date: February 20, 2019 Time: 9:30 a.m. Location: Council Chambers, Hamilton City Hall 71 Main Street West Stephanie Paparella, Legislative Coordinator (905) 546-2424 ext. 3993 Pages 1. CEREMONIAL ACTIVITIES 1.1 Vic Djurdjevic - Tesla Medal Awarded, by the Tesla Science Foundation United States, to the City of Hamilton in Recognition of the City Support and Recognition of Nikola Tesla (no copy) 2. APPROVAL OF AGENDA (Added Items, if applicable, will be noted with *) 3. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST 4. APPROVAL OF MINUTES OF PREVIOUS MEETING 4.1 February 6, 2019 5 5. COMMUNICATIONS 6. DELEGATION REQUESTS 6.1 Tim Potocic, Supercrawl, to outline the current impact of the Festival to 35 the City of Hamilton (For the March 20, 2019 GIC) 6.2 Ed Smith, A Better Niagara, respecting the Niagara Peninsula 36 Conservation Authority (NPCA) (For the March 20, 2019 GIC) Page 2 of 198 7. CONSENT ITEMS 7.1 Barton Village Business Improvement Area (BIA) Revised Board of 37 Management (PED19037) (Wards 2 and 3) 7.2 Residential Special Event Parking Plan for the 2019 Canadian Open Golf 40 Tournament (PED19047) (Ward 12) 7.3 Public Art Master Plan 2016 Annual Update (PED19053) (City Wide) 50 8. PUBLIC HEARINGS / DELEGATIONS 8.1 Vic Djurdjevic, Nikola Tesla Educational Corporation, respecting the Tesla Educational Corporation Events and Activities (no copy) 9. STAFF PRESENTATIONS 9.1 2018 Annual Report on the 2016-2020 Economic Development Action 64 Plan Progress (PED19036) (City Wide) 10. DISCUSSION -

2030 Commonwealth Games Hosting Proposal – Part 1

Appendix B to Report PED18108(b) Page 1 of 157 2030 Commonwealth Games Hosting Proposal – Part 1 – October 23, 2019 – Appendix B to Report PED18108(b) Page 2 of 157 !"#"$%&''&()*+,-.$/+'*0$1$%+(23-45*$6+5-$7$1$&89:;<=$!#>$!"7?$ $ -C;D<$:G$%:A9<A9F$ $ $ #$ %&'"()*)+,"-+'"./0"!121"3450*" 7H7H 5<9I=AJAK$9:$9E<$6DC8<$)E<=<$39$+DD$L<KCAHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH M$ 7H!H ,<KC8N$:G$9E<$7?#"$L=J9JFE$*@OJ=<$/C@<FHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH P$ 7H#H +$%<A9<AC=N$%<D<;=C9J:A HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH Q$ 7HMH &I=$RJFJ:A$G:=$!"#" HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH ?$ 7HPH -=CAFG:=@JAK$&I=$%J9N HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH 7"$ 7HPH7 (<B$0O:=9$SC8JDJ9J<FHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH 7"$ 7HPH! LIJDTJAK$.C@JD9:AUF$0O:=9$-:I=JF@$%COC8J9N HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH 77$ 7HPH# 2J=<89$*8:A:@J8$3@OC89 HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH 7!$ 7HPHM -=CT<$CAT$3AV<F9@<A9$&OO:=9IAJ9J<FHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH 7#$ 7HPHP +GG:=TC;D<$.:IFJAK HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH 7M$ 7HPHQ .C@JD9:AUF$0IF9CJAC;D<$SI9I=<$W$/=<<AJAK$9E<$/C@<FHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH 7M$ 7HPHX *AKCKJAK$R:DIA9<<=F -

Life Lease Housing Advantage

“There’s a vintage that comes with age and experience.” BON JOVI THE VOICE OF ST. ELIZABETH MILLS Vol. 5 2018 Live Every Day Like You’re On Resort-style Living at Upper Mill Pond Vacation See more on page TWO LOCAL LOVE LIFE LEASE IN THE VILLAGE WHO’S WHO ZESTful EVENTS Ten Reasons to Life Lease 8 Great Reasons Meet The Special Canada Day Live in Hamilton Housing to Buy at Sabatino’s Celebration What a great place to live! Advantage Upper Mill Pond They fell in love with Special Canada Day Celebration at Upper Mill Pond The Village at St. Elizabeth Mills Where the smart money is. Buy now at pre-construction prices! Don’t’ Miss Out! FOUR SIX SEVEN SEVEN EIGHT VOL. 5 2018 The Village News The Voice of St. Elizabeth Mills LIVINGWITHZEST.COM Fitness Club Part of the state-of-the-art Health Club, the Fitness Centre is outfitted with the latest cardio and gym equipment within a bright and beautiful setting that will make you look forward to working out. LIVE EVERY DAY LIKE IT’S A VACATION It isn’t just the incredible Health Club. It isn’t just the Juice Bar in the lobby or the stunning recreational space. Pool & Spa It’s the attitude of fun and action that makes Upper Mill Pond The stunning swimming pool at the perfect place to live. Upper Mill Pond offers 5-star luxury with bright windows that overlook the beautiful grounds and lots of places to relax with friends. Suites at Upper Mill Pond are on sale now. -

Arcelormittal Dofasco Inc. Flat Carbon Steel

ArcelorMittal Dofasco Inc. Flat Carbon Steel March 1st, 2018 To Whom It May Concern: Re: ArcelorMittal Dofasco Product Compliance with LEED® Green Building System Requirements – Recycled Content and Regional Materials We confirm that building structures and components made from ArcelorMittal Dofasco flat rolled steel comply with the Recycled Content and Regional Materials requirements outlined under the Materials and Resources key performance category of LEED® rating systems. The details of these specific contributions are outlined below. Recycled Content Recycled steel is an essential raw material for ArcelorMittal Dofasco steelmaking operations, but especially for our electric arc furnace (EAF) steelmaking stream, which uses >85% steel scrap. The sheet steel produced via EAF steelmaking is applied to a wide variety of building products, and uses an average of 24% pre-consumer scrap and 38% post-consumer scrap. These recycled content categories are defined in accordance with the terms of CAN/CSA-ISO 14021, and do not include “home scrap”, which is internally generated scrap steel from steel processing operations. Regional Materials ArcelorMittal Dofasco’s steelmaking operations are located in Hamilton, Ontario, a scrap-rich region of Canada due to the large amount of auto part production, general manufacturing and metal processing that occurs in the area, as well as the high collection rates generated from municipal “blue box” recycling programs. While it is not possible to identify the exact location from which all steel scrap is collected, we can confirm that the steel scrap used in our steelmaking operations is acquired from several recycling facilities located within 5 km of our Hamilton steel mill, which for the purpose of the LEED® green building program, is considered the raw material extraction point. -

REPORT 16-026 10:30 A.M

SPECIAL GENERAL ISSUES COMMITTEE REPORT 16-026 10:30 a.m. Tuesday, October 25, 2016 Council Chambers Hamilton City Hall 71 Main Street West _________________________________________________________________________ Present: Mayor F. Eisenberger, Deputy Mayor D. Skelly (Chair) Councillors T. Whitehead, T. Jackson, C. Collins, S. Merulla, M. Green, J. Farr, A. Johnson, D. Conley, M. Pearson, B. Johnson, L. Ferguson, R. Pasuta, J. Partridge Absent with Regrets: Councillor A. VanderBeek – Personal _________________________________________________________________________ THE GENERAL ISSUES COMMITTEE PRESENTS REPORT 16-026 AND RESPECFULLY RECOMMENDS: 1. Light Rail Transit (LRT) Project Update (PED16199) (City Wide) (Item 5.1) That Report PED16199, respecting the Light Rail Transit (LRT) Project Update, be received. 2. Hamilton Street Railway (HSR) Fare Integration (PW16066) (City Wide) (Item 6.1) That Report PW16066, respecting Hamilton Street Railway (HSR) Fare Integration, be received. 3. Possibility of adding the LRT A-Line at the same time as building the B-Line (7.2) That staff be directed to communicate with Metrolinx to determine the possibility of adding the LRT A-Line at the same time as building the B-Line and report back to the LRT Sub-Committee. Council – November 9, 2016 General Issues Committee October 25, 2016 Report 16-026 Page 2 of 26 . 4. LRT Project Not to Negatively Affect Hamilton’s Allocation of Provincial Gas Tax Revenue or Future Federal Infrastructure Public Transit Funding (Item 7.3) That the Province of Ontario be requested to commit that the Hamilton Light Rail Transit (LRT) Project will not negatively affect Hamilton’s allocation of Provincial Gas Tax Funding or Future Federal Infrastructure Public Transit Funding 5. -

Manufacturers and Industrial Development Policy in Hamilton, 1890-1910 Diana J

Document generated on 09/27/2021 1:09 a.m. Urban History Review Revue d'histoire urbaine Manufacturers and Industrial Development Policy in Hamilton, 1890-1910 Diana J. Middleton and David F. Walker Volume 8, Number 3, February 1980 Article abstract After failing to establish Hamilton as a major wholesaling centre, businessmen URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1019361ar in the city concentrated their attentions increasingly on the manufacturing DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1019361ar sector. City Council policies were extremely supportive of this focus, particularly in the period from 1890 to 1910, which is examined in this paper. See table of contents Manufacturers themselves, however, are shown to have played a minor role in Council's activities. None of the key figures in promoting pro-development policies in Hamilton were manufacturers, despite the fact that those policies Publisher(s) were designed primarily to stimulate manufacturing. At the forefront, rather, were professional men with business interests, supported mainly by Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine merchants. ISSN 0703-0428 (print) 1918-5138 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Middleton, D. J. & Walker, D. F. (1980). Manufacturers and Industrial Development Policy in Hamilton, 1890-1910. Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine, 8(3), 20–46. https://doi.org/10.7202/1019361ar All Rights Reserved © Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine, 1980 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. -

Arcelormittal Dofasco Inc. Flat Carbon Steel February 27Th, 2020 To

ArcelorMittal Dofasco Inc. Flat Carbon Steel February 27th, 2020 To Whom It May Concern: Re: ArcelorMittal Dofasco Product Compliance with LEED® Green Building System Requirements – Recycled Content and Regional Materials We confirm that building structures and components made from ArcelorMittal Dofasco flat rolled steel comply with the Recycled Content and Regional Materials requirements outlined under the Materials and Resources key performance category of LEED® rating systems. The details of these specific contributions are outlined below. Recycled Content Recycled steel is an essential raw material for ArcelorMittal Dofasco steelmaking operations, but especially for our electric arc furnace (EAF) steelmaking stream. The sheet steel produced via EAF steelmaking is applied to a wide variety of building products, and uses an average of 21% pre-consumer scrap and 32% post-consumer scrap. These recycled content categories are defined in accordance with the terms of CAN/CSA-ISO 14021, and do not include “home scrap”, which is internally generated scrap steel from steel processing operations. Regional Materials ArcelorMittal Dofasco’s steelmaking operations are located in Hamilton, Ontario, a scrap-rich region of Canada due to the large amount of auto part production, general manufacturing and metal processing that occurs in the area, as well as the high collection rates generated from municipal “blue box” recycling programs. While it is not possible to identify the exact location from which all steel scrap is collected, we can confirm that the steel scrap used in our steelmaking operations is acquired from several recycling facilities located within 5 km of our Hamilton steel mill, which for the purpose of the LEED® green building program, is considered the raw material extraction point.