Blaming Helen: Vergil’S Deiphobus and the Tradition of Dead Men Talking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer's Iliad Senior Thesis

Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer’s Iliad Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Undergraduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Classical Studies Professor Joel Christensen, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts By Joana Jankulla May 2018 Copyright by Joana Jankulla 1 Copyright by Joana Jankulla © 2018 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Joel Christensen. Thank you, Professor Christensen for guiding me through this process, expressing confidence in me, and being available whenever I had any questions or concerns. I would not have been able to complete this work without you. Secondly, I would like to thank Professor Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Professor Cheryl Walker for reading my thesis and providing me with feedback. The Classics Department at Brandeis University has been an instrumental part of my growth in my four years as an undergraduate, and I am eternally thankful to all the professors and staff members in the department. Thank you to my friends, specifically Erica Theroux, Sarah Jousset, Anna Craven, Rachel Goldstein, Taylor McKinnon and Georgie Contreras for providing me with a lot of emotional support this year. I hope you all know how grateful I am for you as friends and how much I have appreciated your love this year. Thank you to my mom for FaceTiming me every time I was stressed about completing my thesis and encouraging me every step of the way. Finally, thank you to Ian Leeds for dropping everything and coming to me each time I needed it. -

Anna Bonifazi, Homer's Versicolored Fabric. the Evocative Power of Ancient Greek Epic Word-Making

New England Classical Journal Volume 40 Issue 3 Pages 213-216 11-2013 Anna Bonifazi, Homer's Versicolored Fabric. The Evocative Power of Ancient Greek Epic Word-Making. Anne Mahoney Tufts University Follow this and additional works at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/necj Recommended Citation Mahoney, Anne (2013) "Anna Bonifazi, Homer's Versicolored Fabric. The Evocative Power of Ancient Greek Epic Word-Making.," New England Classical Journal: Vol. 40 : Iss. 3 , 213-216. Available at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/necj/vol40/iss3/5 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in New England Classical Journal by an authorized editor of CrossWorks. BOOK REVIEWS Anna Bonifazi, Homer's Versicolored Fabric. The Evocative Power of Ancient Greek Epic Word-Making. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies, 2012. Distributed by Harvard University Press. Pp. 350. Paper (ISBN 978-0-674- 06062-3) $24.95. his is a linguistic study of a1h6s and related words in epic, particularly the Odyssey but also the Iliad. Bonifazi considers first Thow a11T6s and EKE'ivos are contrasted when they refer to Odysseus, then how all the various av- words are similar. Her main tool is pragmatics, building on work by many scholars on discourse grammar in both Greek and Latin. Because she goes through a lot of basic background in this area of linguistics, with a copious bibliography, 25 pages, the book seems accessible to non-linguist classicists, though this is not really an introduction to pragmatics. In the introduction, Bonifazi says that "the general aim of this work is to contribute to an update of the grammatical accounts of some words in accord with notions and concepts from contemporary linguistics that are applicable to Homer" (10), observing that this kind of study adds precision to our understanding of pronouns, particles, and similar words, and that attention to the dialogue context can "shed more light on the standpoint of either the author or the internal characters" (11). -

Brothers Fighting Together in the Iliad

BROTHERS FIGHTING TOGETHER IN THE ILIAD I We find in the Iliad numerous pairs of brothers (or half brothers on the father's side, or first cousins on the father's side) fighting together on foot or in the combination of chario teer-paraibates 1). And this is not confined to the men who are said to have taken part in the Trojan war, but it embraces the "mythical world of the past" 2), that of the demigods 3), the rivers 4) and even the gods 5). Moreover, if we turn to the leaders of the various groups of Greeks and Trojans, as given in book 11, we find that a 1). Such for example are: Ajax Telarnonius and Teucer (the Atav'ts, cf. p. 291), Mynes and Epistrophus (II 692f.), Phegeus and Idaeus (V 10f.), Echemon and Chromios (V 159 f.), Krethon and Orsilochus (V 542 f,), Aesepus and Pedasus (VI 21 f.), Hector and Alexander (VI 514 f., cf. VII 1 f.), Ascalaphus and lalmenus (IX 82f., cf. II 512), Peisandrus and Hip polochus (XI 122 f.), Hippodamus and Hypeirochus (XI 328 f.), Charops and Socus (XI 426 f.), the Molione (XI 750, 709 f.; XXIII 638 f.), Polybus, Agenor and Akarnas (XI 59 f.), Helenos and Deiphobus (XII 94 f,), Archelochus and Akamas (XIV 463 f.), Hector and Cebriones (XII 86 f.), Deiphobus and Polites (XIII 533 f.), Podarces and Iphiclus (XIII 693 f,), Deiphohus and Helenos (XIII 780 f.), Ascanius and Morys (XIII 792 f.), Atymnius and Maris (XVI 317 f.), Antilochus and Thrasymedes (XVI 322; XVII 377 f.; XVII 705), Euphorbus and Polydamas (XVII 1 f.), Chromius and Aretus (XVII 492 f.), Aretus and Hector (XVII 516), Polydorus and Hector (XX 407 f,), Laogonus and Dardanus (XX 460 f.), or Deiphobus and Hector (XXII 226 f.). -

THE ODYSSEY of HOMER Translated by WILLIAM COWPER LONDON: PUBLISHED by J·M·DENT·&·SONS·LTD and in NEW YORK by E·P·DUTTON & CO to the RIGHT HONOURABLE

THE ODYSSEY OF HOMER Translated by WILLIAM COWPER LONDON: PUBLISHED by J·M·DENT·&·SONS·LTD AND IN NEW YORK BY E·P·DUTTON & CO TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE COUNTESS DOWAGER SPENCER THE FOLLOWING TRANSLATION OF THE ODYSSEY, A POEM THAT EXHIBITS IN THE CHARACTER OF ITS HEROINE AN EXAMPLE OF ALL DOMESTIC VIRTUE, IS WITH EQUAL PROPRIETY AND RESPECT INSCRIBED BY HER LADYSHIP’S MOST DEVOTED SERVANT, THE AUTHOR. THE ODYSSEY OF HOMER TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH BLANK VERSE BOOK I ARGUMENT In a council of the Gods, Minerva calls their attention to Ulysses, still a wanderer. They resolve to grant him a safe return to Ithaca. Minerva descends to encourage Telemachus, and in the form of Mentes directs him in what manner to proceed. Throughout this book the extravagance and profligacy of the suitors are occasionally suggested. Muse make the man thy theme, for shrewdness famedAnd genius versatile, who far and wideA Wand’rer, after Ilium overthrown,Discover’d various cities, and the mindAnd manners learn’d of men, in lands remote.He num’rous woes on Ocean toss’d, endured,Anxious to save himself, and to conductHis followers to their home; yet all his carePreserved them not; they perish’d self-destroy’dBy their own fault; infatuate! who devoured10The oxen of the all-o’erseeing Sun,And, punish’d for that crime, return’d no more.Daughter divine of Jove, these things record,As it may please thee, even in our ears.The rest, all those who had perdition ’scapedBy war or on the Deep, dwelt now at home;Him only, of his country and his wifeAlike desirous, in her hollow grotsCalypso, Goddess beautiful, detainedWooing him to her arms. -

(Tom) Palaima Department

CC 303 Intro to Classical Mythology 32925 MWF 12-1:00 JGB 2.324 Palaima, Thomas G. Professor Thomas (Tom) Palaima Department: Classics WAG 123 Mail Code: C3400 Office: Waggener 14AA Office Hours: M 3:30-4:30pm W 10-11:00 am and by appt [email protected] Campus Phone: 471-8837 fax: 471-4111 Dept. 471-5742 Assistant Instructors William (Bill) Farris Dept: Classics WAG 123 Mail Code: C3400 Office: Waggener 11 Office Hours: T 10-11am TH 12:30-1:30pm and by appt [email protected] Campus Phone: NONE fax: 471-4111 Dept. 471-5742 Samantha (Sam) Meyer Department: Classics WAG 123 Mail Code: C3400 Office: Waggener 13 Office Hours: M 9-10am F 1-2pm and by appt [email protected] Campus Phone: NONE fax: 471-4111 Dept. 471-5742 SI sessions: Mondays 5-6pm in CBA 4.330 Thursdays 6-7pm in MEZ 1.210 Supplemental Instruction (SI) consists of weekly voluntary discussion sessions that are aimed at helping students learn and practice study strategies with the course materials. Two sessions are offered each week (while you are absolutely welcome to come to both, you do not need to attend both). These sessions are facilitated by the SI leader, but primarily they are a space for collaborative, student-driven discussion and review. Please let Sam know if you have any questions! Course Description: Greek mythology is mainly a public performance literature embedded in a still primarily oral culture. Ancient Greek mythmakers (the word muthos means simply “something uttered,” i.e., what we call a “story”) used their stories in public settings to make sense of their world and to entertain, instruct, ask questions and provoke discussion among people who lived mainly in “continual fear and danger of violent death, [in historical periods when] the life of man [was] solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” (Thomas Hobbes). -

Eumaeus, Evander, and Augustus: Dionysius and Virgil on Noble Simplicity*

Eumaeus, Evander, and Augustus: Dionysius and Virgil on Noble Simplicity* Casper C. de Jonge Introduction Eumaeus might not be the first character to come to mind when we think of Homeric epic as Princes’ Mirror. To be sure, Eumaeus is of royal descent: his father was Ctesius, son of Ormenus, king of the island Syria.1 But Eumaeus is also a slave: as a child he was sold to Laertes and, having been raised together with Odysseus’ sister Ctimene, he became the family’s swineherd.2 Eumaeus is one of the lower-status figures to which the Odyssey pays more attention than the Iliad. Like Eurycleia, the other prominent lowly character, Eumaeus is portrayed as a loyal servant. During Odysseus’ absence he takes good care of his master’s animals (Od. 14.5–28, 524–533), although he is defenceless against the suitors, who continually force him to send in pigs for their feasts (Od. 14.17– 20). The detailed description of Eumaeus’ pig-farm (Od. 14.7–22) brings out its modesty in comparison with the luxurious palaces of kings like Menelaus, Alcinous, and Odysseus. But with its vestibule (πρόδομος), courtyard (αὐλή), and defensive wall the farm adequately fulfils its function.3 When Odysseus arrives in Ithaca, Eumaeus gives him hospitality and offers him a double meal (Od. 14.72–111 and 14.410–454) and a bed (Od. 14.454–533), not yet knowing that his guest is actually his master. The next day the host and his guest share * The research for this paper was funded by a grant awarded by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (nwo). -

Penelope, Odysseus, and the Teleologies of the Odyssey

Putting an End to Song: Penelope, Odysseus, and the Teleologies of the Odyssey Emily Hauser Helios, Volume 47, Number 1, Spring 2020, pp. 39-69 (Article) Published by Texas Tech University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/hel.2020.0001 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/765967 [ Access provided at 28 Dec 2020 07:35 GMT from University of Washington @ Seattle ] Putting an End to Song: Penelope, Odysseus, and the Teleologies of the Odyssey EMILY HAUSER Abstract Book 1 of the Odyssey presents us with the first bard-figure of the poem, singing what in many ways is an analogue to the Odyssey with “the return of the Greeks”; yet when Penelope appears, it is to attempt to put an end to his song. I use this scene as a starting point to suggest that Penelope is deeply implicated in narrative endings in the Odyssey. Looking at the end or τέλος of the poem through a system- atic study of its “closural allusions,” I argue that a teleological analysis of Penelope’s character in relation to endings may both resolve some of the issues in her inter- pretation thus far, and open up new avenues for the reading of the Odyssey as a poem informed by endings. I. Introduction Penelope’s first appearance in the Odyssey (1.325–144) is to make a request of Phe- mius the bard, who is singing the tale of the Greeks’ return from Troy, the Ἀχαιῶν νόστος (1.326). Phemius’s song of the Greek νόστος (return), of course, mirrors the plot of the Odyssey itself, which has opened only a few hundred lines before with the plea to the Muse to sing of Odysseus and his companions’ return (νόστος, 1.5) from Troy.1 Penelope, however, interrupts the narrative flow and asks the bard to cease singing because of the pain his tale is causing her (1.340–342): ‘ταύτης δ᾽ ἀποπαύε᾽ ἀοιδῆς λυγρῆς, ἥ τέ μοι αἰεὶ ἐνὶ στήθεσσι φίλον κῆρ τείρει . -

Llt 121 Classical Mythology Lecture 36 Good Morning

LLT 121 CLASSICAL MYTHOLOGY LECTURE 36 GOOD MORNING AND WELCOME TO LLT 121 CLASSICAL MYTHOLOGY IN WHICH WE TAKE UP PROBABLY THE SECOND OLDEST STORY IN THE BOOK, THE SECOND OLDEST GREAT EPIC IN WESTERN LITERATURE, THE ILIAD OF HOMER. THE GILGAMESH EPIC OF THE VARIOUS MESOPOTAMIAN PEOPLE IS OLDER. THIS IS NUMBER TWO. IT TRIES HARDER. WHEN LAST WE LEFT OFF ACHILLES WAS STILL POUTING BY THE SIDE OF HIS SWIFT, BLACK SHIPS WITH HIS FRIEND PATROCLUS. YOU WILL REMEMBER THAT ACHILLES HAS ALREADY TURNED DOWN ONE OFFER FROM AGAMEMNON FOR A COMPLETE APOLOGY, BRISEIS BACK, VALUABLE PRIZES, THE WHOLE NINE YARDS. JUST COME BACK TO US ACHILLES. WE NEED YOU. ACHILLES SAYS I'VE GOT TWO POSSIBLE FATES. ONE, I CAN DIE IN BATTLE, WIN LOTS OF GLORY, AND BE FAMOUS FOREVER AFTER. OR B, I COULD LIVE TO A LONG, GREAT OLD AGE, BE REAL HAPPY AND LEAVE BEHIND NO ARITAE OR VIRTUE AND HAVE NO KLEOS OR FAME AFTER MY DEATH. I MIGHT SAY NUMBER TWO IS LOOKING BETTER. SO THE GREEKS GET THEIR BUTTS KICKED FOR ANOTHER THREE OR FOUR BOOKS. FINALLY, NESTOR THE 300 YEAR OLD GUY WHO TALKS JUST ABOUT FOREVER COMES UP WITH AN IDEA FOR PATROCLUS. PATROCLUS, I'M GOING TO TRY TO PERSUADE YOU TO PUT ON THE ARMOR OF ACHILLES AND GO INTO BATTLE. PATROCLUS FINALLY AGREES TO GET NESTOR TO SHUT UP AND ALSO MAYBE IT'S NOT EASY TO BE GILLIGAN, SCOTTIE PIPPIN, OR ED MCMAHON, THE NUMBER TWO BANANA. YOU WANT TO.STAND IN THE LIMELIGHT AND DO A FEW OF THOSE ON PUBLISHERS CLEARINGHOUSE SWEEPSTAKES COMMERCIALS OF YOUR OWN. -

The Untold Death of Laertes. Revaluating Odysseus's Meeting

The untold death of Laertes. Revaluating Odysseus’s meeting with his father Abstract This article discusses the narrative function and symbolism of the Laertes scene in the twenty- fourth book of the Odyssey. By pointing out the scene’s connections to other passages (the story of Penelope’s web, the first and second nekuia , the farewellto the Phaeaceans, the Argus scene, but also the twenty-fourth book of the Iliad) and by tackling some of the textualproblems that it poses (the apparent cruelty of Odysseus’s lies to his father, the double layers of meaning in his fictions, the significance of the sèma of the trees), this article aims to point out how the Laertes scene is tightly woven into the larger thematic and symbolicaltissue of the Odyssey. Odysseus’s reunion with his father is conclusive to the treatment of some important themes such as death and burial, reciprocalsense of love and duty and the succession of generations. It willbe argued that the untold death of Laertes becomes paradigmatic for the fate Odysseus himself chooses, and for the way in which the epic as a whole deals with the problem of mortality. Keywords Odyssey, Laertes, symbolism, mortality, burial, reciprocity Laertes, the old father of Odysseus, is a somewhat forgotten character. He is mostly considered to be of minor importance to the plot of the Odyssey, and his reunion with his son in the twenty-fourth book is often seen as a more or less dispensable addendum to the realclimax, the recognition scene with Penelope. In this article, I aim to readjust this view by exploring the context and significance of this final meeting. -

Euripides.The Women of Troy

THE WOMEN OF TROY * Characters: PosnrnoN, God of the Sea AtunNE, a goddess HEclnE, wldow of Prian Kng of TroY Cnonus of caPtive Troian women T.arrnYsru s, a Greek herald C e s s a bl P t' t, daughtcr of Heeabe of Hecabe ANo no tola c nu, 1o'ghti'inJaw Mrunrlus, a general of the Gteek army HEtElr, his wife * the city's uptyry t Scene: The ruins of Troy, two days aftu \e[1re buildings' dawn. First are seen'o'nly siihoiettes of shattued on the god ;;;:'r-r' ira gt * ,nd;i';;s smokel thei tightfalk P osnrooN. PosntuoN: 1 from the salt depths of the Aegean Sea' circling dance: *f,;"o*" the white f..t oiNt"ids treaJtheir were.my city' I am Poseidon. Troy and its people Til;;;;;iw"ll, to*"^' I and Apollo built - "nd has not faded' Squared everY stone i" ii; my tdction "td Argive spear' Ni* it.y lies dead under the conquering Stripped, iacked and smouldering' made Epeius, a Phocian from Parnassus' with armed men' To Athene's th"t horse pregnant il* sent it a;iJbt afl'future ages the"'wo-oden Horse' and through the Trojan i" gfta"1 weighty *iih hiddto death' walls. run with blood; The sacred groves are deserted; the temples B.O.P. - J 9o EURIPIDES -701 THE WOMEN OF TROY 9r On Zeus fhe Protector's altar-steps priam lies dead. ArnrNn: Measureless gold and all the loot of Troy qoes down great god honoured by gods and my father's To theGreek and now rhey wait foru follo*iog * You are a - thip-s; brother: To make glad, after ten long years, with the sight Jf wives and children May our old feud be buried? I have something to say to you. -

The Trojan War

THE TROJAN WAR PART ONE: THE ORIGINS OF THE TROJAN WAR have actually revealed weaker stonework on the western walls of Troy, suggesting that a genuine difference in construction led to the myth that The city of Troy had several mythical founders and kings, the two gods built the other walls. including Teucer, Dardanus, Tros, Ilus and Assaracus. The most widely accepted story makes Ilus the actual founder, Mythical reasons behind the Trojan War and from him the city took the name it was best-known by in ancient times, Ilium. In an episode similar to the founding During Priam's of Thebes, Ilus was given a cow and told to found a city lifetime Troy where it first lay down. As instructed, he followed the reached its animal, and on the land where it rested drew up the greatest boundaries of his city. He then received an additional sign prosperity, but from the gods, a legless wooden statue called the Palladium, when he was a which dropped from the heavens with the message that it very old man it should be carefully guarded as it 'brought empire'. Some say was tota lly it was a statue of Athene's friend Pallas, but most believe it destroyed after a was of Athene herself and that this statue was to make Troy ten-year siege by a great city. warriors from Greece. Some say Laomedon's Troy Zeus himself Ilus was succeeded by his son Laomedon, who built great caused the Trojan walls around his city with the help of a mortal, Aeacus, and War to thin out the two gods Poseidon and Apollo. -

That Ingenious Hero

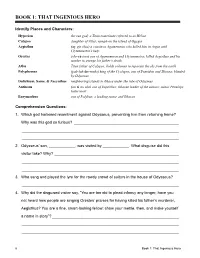

BOOK 1: THAT INGENIOUS HERO Identify Places and Characters: Hyperion the sun god; a Titan sometimes referred to as Helios Calypso daughter of Atlas; nymph on the island of Ogygia Aegisthus (ay-gis-thus) a cousin to Agamemnon who killed him in Argos with Clytemnestra’s help Orestes (ohr-es-teez) son of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra; killed Aegisthus and his mother to avenge his father’s death Atlas Titan father of Calypso; holds columns to separate the sky from the earth Polyphemus (pah-luh-fee-muhs) king of the Cyclopes; son of Poseidon and Thoosa; blinded by Odysseus Dulichium, Same, & Zacynthus neighboring islands to Ithaca under the rule of Odysseus Antinous (an-ti-no-uhs) son of Eupeithes; Ithacan leader of the suitors; suitor Penelope hates most Eurymachus son of Polybus; a leading suitor and Ithacan Comprehension Questions: 1. Which god harbored resentment against Odysseus, preventing him from returning home? Why was this god so furious? ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ 2. Odysseus’ son, ____________, was visited by ____________. What disguise did this visitor take? Why? _________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ 3. Who sang and played the lyre for the rowdy crowd of suitors in the house of Odysseus? ________________________________________________________________________