Second Screen Interaction in the Cinema: Experimenting with Transmedia Narratives and Commercialising User Participation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Playstation®4 Launches Across the United States

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PLAYSTATION®4 LAUNCHES ACROSS THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA With the PS4™system, Sony Computer Entertainment Welcomes Gamers to a New Era of Rich, Immersive Gameplay Experiences TOKYO, November 15, 2013 – Sony Computer Entertainment Inc. (SCEI) today launched PlayStation®4 (PS4™), a system built for gamers and inspired by developers. The PS4 system is now available in the United States and Canada at a suggested retail price of USD $399 and CAD $399, arriving with a lineup of over 20 first- and third-party games, including exclusive titles like Knack™ and Killzone: Shadow Fall™. In total, the PS4 system will have a library of over 30 games by the end of the year. *1 “Today’s launch of PS4 represents a milestone for all of us at PlayStation, our partners in the industry, and, most importantly, all of the PlayStation fans who live and breathe gaming every day,” said Andrew House, President and Group CEO, Sony Computer Entertainment Inc. “With unprecedented power, deep social capabilities, and unique second screen features, PS4 demonstrates our unwavering commitment to delivering phenomenal play experiences that will shape the world of games for years to come.” The PS4 system enables game developers to realize their creative vision on a platform specifically tuned to their needs, making it easier to build huge, interactive worlds in smooth 1080p HD resolution.*2 Its supercharged PC architecture – including an enhanced Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) and 8GB of GDDR5 unified system memory – is designed to ease game creation and deliver a dramatic increase in the richness of content available on the platform. -

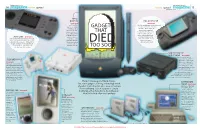

Gadgets That Too Soon

14 centre spread centre spread 15 DECEMBER 07-13, 2014 DECEMBER 07-13, 2014 APPLE NEWTON SEGA GAME GEAR It was a personal This 8-bit handheld game console was released digital assistant (PDA) GADGETS in response to Nintendo's Game Boy. It before palm and a was held lengthwise at the sides tablet before the iPad. (preventing the cramping of By modern standards, THAT hands) and had a backlit, colour it was pretty basic — it LCD screen, allowing for clearer could take notes, store and more vibrant visuals. It was ATARI LYNX contacts, and manage also praised for its processing Atari’s little handheld sported the rst colour LCD, calendars. It had a power. Its unique game library before Sega’s Game Gear, and was cheaper with stylus, and could even and price point gave it an better battery life in comparison. It ultimately lost translate handwriting edge over its competitors the game to Nintendo. It was nearly twice the into text. It could also DIED size of Game Boy's postage stamp screen be used to send a fax and oered much better graphics TOO SOON 3DO INTERACTIVE MULTIPLAYER Manufactured by Panasonic, Sanyo and GoldStar, 3DO was SEGA DREAMCAST the rst game system to use CDs for content delivery. The It was superior to most other increase in data storage led to syst ems at the time with built-in better 3D graphics. Also, the modem for Internet support and gaming machine was one of the online play as well as a controller rst entries in the 32-bit that allowed second-screen gaming. -

Malcolm's Video Collection

Malcolm's Video Collection Movie Title Type Format 007 A View to a Kill Action VHS 007 A View To A Kill Action DVD 007 Casino Royale Action Blu-ray 007 Casino Royale Action DVD 007 Diamonds Are Forever Action DVD 007 Diamonds Are Forever Action DVD 007 Diamonds Are Forever Action Blu-ray 007 Die Another Day Action DVD 007 Die Another Day Action Blu-ray 007 Dr. No Action VHS 007 Dr. No Action Blu-ray 007 Dr. No DVD Action DVD 007 For Your Eyes Only Action DVD 007 For Your Eyes Only Action VHS 007 From Russia With Love Action VHS 007 From Russia With Love Action Blu-ray 007 From Russia With Love DVD Action DVD 007 Golden Eye (2 copies) Action VHS 007 Goldeneye Action Blu-ray 007 GoldFinger Action Blu-ray 007 Goldfinger Action VHS 007 Goldfinger DVD Action DVD 007 License to Kill Action VHS 007 License To Kill Action Blu-ray 007 Live And Let Die Action DVD 007 Never Say Never Again Action VHS 007 Never Say Never Again Action DVD 007 Octopussy Action VHS Saturday, March 13, 2021 Page 1 of 82 Movie Title Type Format 007 Octopussy Action DVD 007 On Her Majesty's Secret Service Action DVD 007 Quantum Of Solace Action DVD 007 Quantum Of Solace Action Blu-ray 007 Skyfall Action Blu-ray 007 SkyFall Action Blu-ray 007 Spectre Action Blu-ray 007 The Living Daylights Action VHS 007 The Living Daylights Action Blu-ray 007 The Man With The Golden Gun Action DVD 007 The Spy Who Loved Me Action Blu-ray 007 The Spy Who Loved Me Action VHS 007 The World Is Not Enough Action Blu-ray 007 The World is Not Enough Action DVD 007 Thunderball Action Blu-ray 007 -

Amongst Friends: the Australian Cult Film Experience Renee Michelle Middlemost University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2013 Amongst friends: the Australian cult film experience Renee Michelle Middlemost University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Middlemost, Renee Michelle, Amongst friends: the Australian cult film experience, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Social Sciences, Media and Communication, University of Wollongong, 2013. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/4063 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Amongst Friends: The Australian Cult Film Experience A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY From UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG By Renee Michelle MIDDLEMOST (B Arts (Honours) School of Social Sciences, Media and Communications Faculty of Law, Humanities and The Arts 2013 1 Certification I, Renee Michelle Middlemost, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of Social Sciences, Media and Communications, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Renee Middlemost December 2013 2 Table of Contents Title 1 Certification 2 Table of Contents 3 List of Special Names or Abbreviations 6 Abstract 7 Acknowledgements 8 Introduction -

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror Barry Keith Grant Brock University [email protected] Abstract This paper offers a broad historical overview of the ideology and cultural roots of horror films. The genre of horror has been an important part of film history from the beginning and has never fallen from public popularity. It has also been a staple category of multiple national cinemas, and benefits from a most extensive network of extra-cinematic institutions. Horror movies aim to rudely move us out of our complacency in the quotidian world, by way of negative emotions such as horror, fear, suspense, terror, and disgust. To do so, horror addresses fears that are both universally taboo and that also respond to historically and culturally specific anxieties. The ideology of horror has shifted historically according to contemporaneous cultural anxieties, including the fear of repressed animal desires, sexual difference, nuclear warfare and mass annihilation, lurking madness and violence hiding underneath the quotidian, and bodily decay. But whatever the particular fears exploited by particular horror films, they provide viewers with vicarious but controlled thrills, and thus offer a release, a catharsis, of our collective and individual fears. Author Keywords Genre; taboo; ideology; mythology. Introduction Insofar as both film and videogames are visual forms that unfold in time, there is no question that the latter take their primary inspiration from the former. In what follows, I will focus on horror films rather than games, with the aim of introducing video game scholars and gamers to the rich history of the genre in the cinema. I will touch on several issues central to horror and, I hope, will suggest some connections to videogames as well as hints for further reflection on some of their points of convergence. -

The Birth of Haptic Cinema

The Birth of Haptic Cinema An Interactive Qualifying Project Submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science by Panhavuth Lau Jordan Stoessel Date: May 21, 2020 Advisor: Brian Moriarty IMGD Professor of Practice Abstract This project examines the history of The Tingler (1959), the first motion picture to incorporate haptic (tactile) sensations. It surveys the career of its director, William Castle, a legendary Hollywood huckster famous for his use of gimmicks to attract audiences to his low- budget horror films. Our particular focus is Percepto!, the simple but effective gimmick created for The Tingler to deliver physical “shocks” to viewers. The operation, deployment and promotion of Percepto! are explored in detail, based on recently-discovered documents provided to exhibitors by Columbia Pictures, the film’s distributor. We conclude with a proposal for a method of recreating Percepto! for contemporary audiences using Web technologies and smartphones. i Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... i Contents ........................................................................................................................................ ii 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 2. William Castle .......................................................................................................................... -

Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Washington, D.C. in Re

Electronically Filed Docket: 14-CRB-0010-CD/SD (2010-2013) Filing Date: 12/29/2017 03:37:55 PM EST Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Washington, D.C. In re DISTRIBUTION OF CABLE ROYALTY FUNDS CONSOLIDATED DOCKET NO. 14-CRB-0010-CD/SD In re (2010-13) DISTRIBUTION OF SATELLITE ROYALTY FUNDS WRITTEN DIRECT STATEMENT REGARDING DISTRIBUTION METHODOLOGIES OF THE MPAA-REPRESENTED PROGRAM SUPPLIERS 2010-2013 CABLE ROYALTY YEARS VOLUME I OF II WRITTEN TESTIMONY AND EXHIBITS Gregory O. Olaniran D.C. Bar No. 455784 Lucy Holmes Plovnick D.C. Bar No. 488752 Alesha M. Dominique D.C. Bar No. 990311 Mitchell Silberberg & Knupp LLP 1818 N Street NW, 8th Floor Washington, DC 20036 (202) 355-7917 (Telephone) (202) 355-7887 (Facsimile) [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Attorneys for MPAA-Represented Program Suppliers December 29, 2017 Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES Washington, D.C. In re DISTRIBUTION OF CABLE ROYALTY FUNDS CONSOLIDATED DOCKET NO. 14-CRB-0010-CD/SD In re (2010-13) DISTRIBUTION OF SATELLITE ROYALTY FUNDS WRITTEN DIRECT STATEMENT REGARDING DISTRIBUTION METHODOLOGIES OF MPAA-REPRESENTED PROGRAM SUPPLIERS FOR 2010-2013 CABLE ROYALTY YEARS The Motion Picture Association of America, Inc. (“MPAA”), its member companies and other producers and/or distributors of syndicated series, movies, specials, and non-team sports broadcast by television stations who have agreed to representation by MPAA (“MPAA-represented Program Suppliers”),1 in accordance with the procedural schedule set forth in Appendix A to the December 22, 2017 Order Consolidating Proceedings And Reinstating Case Schedule issued by the Copyright Royalty Judges (“Judges”), hereby submit their Written Direct Statement Regarding Distribution Methodologies (“WDS-D”) for the 2010-2013 cable royalty years2 in the consolidated 1 Lists of MPAA-represented Program Suppliers for each of the cable royalty years at issue in this consolidated proceeding are included as Appendix A to the Written Direct Testimony of Jane Saunders. -

New Joysticks Available for Your Atari 2600

May Your Holiday Season Be a Classic One Classic Gamer Magazine Classic Gamer Magazine December 2000 3 The Xonox List 27 Teach Your Children Well 28 Games of Blame 29 Mit’s Revenge 31 The Odyssey Challenger Series 34 Interview With Bob Rosha 38 Atari Arcade Hits Review 41 Jaguar: Straight From the Cat’s 43 Mouth 6 Homebrew Review 44 24 Dear Santa 46 CGM Online Reset 5 22 So, what’s Happening with CGM Newswire 6 our website? Upcoming Releases 8 In the coming months we’ll Book Review: The First Quarter 9 be expanding our web pres- Classic Ad: “Fonz” from 1976 10 ence with more articles, games and classic gaming merchan- Lost Arcade Classic: Guzzler 11 dise. Right now we’re even The Games We Love to Hate 12 shilling Classic Gamer Maga- zine merchandise such as The X-Games 14 t-shirts and coffee mugs. Are These Games Unplayable? 16 So be sure to check online with us for all the latest and My Favorite Hedgehog 18 greatest in classic gaming news Ode to Arcade Art 20 and fun. Roland’s Rat Race for the C-64 22 www.classicgamer.com Survival Island 24 Head ‘em Off at the Past 48 Classic Ad: “K.C. Munchkin” 1982 49 My .025 50 Make it So, Mr. Borf! Dragon’s Lair 52 and Space Ace DVD Review How I Tapped Out on Tapper 54 Classifieds 55 Poetry Contest Winners 55 CVG 101: What I Learned Over 56 Summer Vacation Atari’s Misplays and Bogey’s 58 46 Deep Thaw 62 38 Classic Gamer Magazine December 2000 4 “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to Issue 5 repeat it” - George Santayana December 2000 Editor-in-Chief “Unfortunately, those of us who do remember the past are Chris Cavanaugh condemned to repeat it with them." - unaccredited [email protected] Managing Editor -Box, Dreamcast, Play- and the X-Box? Well, much to Sarah Thomas [email protected] Station, PlayStation 2, the chagrin of Microsoft bashers Gamecube, Nintendo 64, everywhere, there is one rule of Contributing Writers Indrema, Nuon, Game business that should never be X Mark Androvich Boy Advance, and the home forgotten: Never bet against Bill. -

Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND SUBJECT INDEX Film review titles are also Akbari, Mania 6:18 Anchors Away 12:44, 46 Korean Film Archive, Seoul 3:8 archives of television material Spielberg’s campaign for four- included and are indicated by Akerman, Chantal 11:47, 92(b) Ancient Law, The 1/2:44, 45; 6:32 Stanley Kubrick 12:32 collected by 11:19 week theatrical release 5:5 (r) after the reference; Akhavan, Desiree 3:95; 6:15 Andersen, Thom 4:81 Library and Archives Richard Billingham 4:44 BAFTA 4:11, to Sue (b) after reference indicates Akin, Fatih 4:19 Anderson, Gillian 12:17 Canada, Ottawa 4:80 Jef Cornelis’s Bruce-Smith 3:5 a book review; Akin, Levan 7:29 Anderson, Laurie 4:13 Library of Congress, Washington documentaries 8:12-3 Awful Truth, The (1937) 9:42, 46 Akingbade, Ayo 8:31 Anderson, Lindsay 9:6 1/2:14; 4:80; 6:81 Josephine Deckers’s Madeline’s Axiom 7:11 A Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Adewale 8:42 Anderson, Paul Thomas Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Madeline 6:8-9, 66(r) Ayeh, Jaygann 8:22 Abbas, Hiam 1/2:47; 12:35 Akinola, Segun 10:44 1/2:24, 38; 4:25; 11:31, 34 New York 1/2:45; 6:81 Flaherty Seminar 2019, Ayer, David 10:31 Abbasi, Ali Akrami, Jamsheed 11:83 Anderson, Wes 1/2:24, 36; 5:7; 11:6 National Library of Scotland Hamilton 10:14-5 Ayoade, Richard -

July / August 2021 Newsletter

JULY / AUGUST 2021 The Bryant Library, 2 Paper Mill Road, Roslyn, NY 11576 516-621-2240 • www.bryantlibrary.org SUMMER READING PROGRAMS FOR ALL AGES Free gift CHILDREN’S TEENS ADULTS THROUGH SAT., AUGUST 7 TUESDAY, JULY 6 - TUESDAY, JULY 6 - Free, fun, and rewarding! Join our TUESDAY, AUGUST 31 TUESDAY, AUGUST 31 summer reading program and earn Grades 6-12! Track your reading Free Gift For Joining! Stop by the weekly prizes. Children are encour- on READsquared for the chance to Reference Desk to claim your gift. Join aged to read all year, especially win weekly raffles! After you sign us for a summer of reading fun! Weekly during the summer. Our program up, stop by the Reference Desk to raffles, author talks, cooking & baking begins Monday, June 14 and runs pick up your registration prize. Also demonstrations, book & movie discus- through Saturday, August 7 for be sure to flip to Pages 15 & 16 sions, prizes, and more! For Bryant children in Preschool to 5th Grade. for more information on upcoming Library Card Holders Only. To sign up, Registration and recording is all done special events and visit www.bry- visit www.bryantlibrary.org or call the through READsquared (Online) and antlibrary.org to sign up. Limited to Reference Desk (516) 621-2240. All of prizes will be awarded weekly to Bryant Library cardholders only. our Summer Tales special events will participants, while supplies last. The take place on Tuesdays at 1:00 PM via last week of the program there will be Zoom. Flip to Page 9 for more details. -

Playstation App for Mac

Playstation App For Mac 1 / 4 Playstation App For Mac 2 / 4 You can also stream a wide range of PlayStation games with a PS Now subscription on a PC.. Download Playstation App For MacPlaystation Remote App For MacPlaystation App For MacPlaystation App For MacQuick NavigationThe Remote Play app for PC and Mac lets you stream games from your PS4 to your laptop or desktop computer.. Even if you don’t have your PS4’s control, you can use a phone or a tablet as a controller. 1. playstation store 2. playstation 4 3. playstation support Please Note: PS Now does not support Macintosh computers at this time Download the PS Now app, connect a controller and start streaming hundreds of games on demand.. If any of these is your requirement, you should get the PS4 Second Screen right away.. 4 FAQsThis is the tutorial to download PS4 Second Screen PC on Windows 10 and macOS-powered computers.. I wish they release it soon, I don't really like switching to bootcamp for an hour just to play the games. playstation store playstation store, playstation 4, playstation 5, playstation network, playstation, playstation support, playstation 2, playstation login, playstation 1, playstation now, playstation 3 Asian Riddles Free Download PS4 Second Screen also allows adding text or writing in any text area using the connected device. Avervision Cp135 Software download free software Episode 6.5 User Guide For Mac playstation 4 Pengolahan Limbah Stream the entire PS Now game collection to your Windows PC – more than 700 games, on.. My brand new Macbook Pro with 8GB of RAM was running the fan like crazy and couldn't even keep websites loaded. -

Explore Our Newsletter

JULY / AUGUST 2021 The Bryant Library, 2 Paper Mill Road, Roslyn, NY 11576 516-621-2240 • www.bryantlibrary.org SUMMER READING PROGRAMS FOR ALL AGES Free gift CHILDREN’S TEENS ADULTS THROUGH SAT., AUGUST 7 TUESDAY, JULY 6 - TUESDAY, JULY 6 - Free, fun, and rewarding! Join our TUESDAY, AUGUST 31 TUESDAY, AUGUST 31 summer reading program and earn Grades 6-12! Track your reading Free Gift For Joining! Stop by the weekly prizes. Children are encour- on READsquared for the chance to Reference Desk to claim your gift. Join aged to read all year, especially win weekly raffles! After you sign us for a summer of reading fun! Weekly during the summer. Our program up, stop by the Reference Desk to raffles, author talks, cooking & baking begins Monday, June 14 and runs pick up your registration prize. Also demonstrations, book & movie discus- through Saturday, August 7 for be sure to flip to Pages 15 & 16 sions, prizes, and more! For Bryant children in Preschool to 5th Grade. for more information on upcoming Library Card Holders Only. To sign up, Registration and recording is all done special events and visit www.bry- visit www.bryantlibrary.org or call the through READsquared (Online) and antlibrary.org to sign up. Limited to Reference Desk (516) 621-2240. All of prizes will be awarded weekly to Bryant Library cardholders only. our Summer Tales special events will participants, while supplies last. The take place on Tuesdays at 1:00 PM via last week of the program there will be Zoom. Flip to Page 9 for more details.