Mapping New Jerusalem: Space, National Identity and Power in British Espionage Fiction 1945-79

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dupagne and Seel’S (1998) High- Cism Reserved for the “Class Traitor” Jenkins

Journalism Studies, Volume 5, Number 4, 2004, pp. 551–562 Book Reviews The Troubles of Journalism: a critical look The Troubles of Journalism is a small book with at what’s right and wrong with the press, big goals. It purports to diagnose “the causes of 2nd edn the malaise that seems to grip the news business WILLIAM A. HACHTEN today,” as well as to catalog the major economic, social, cultural and technological changes in Women and Journalism American journalism; to evaluate the impact of DEBORAH CHAMBERS,LINDA STEINER AND CAROLE the changes and the criticism they have trig- FLEMING gered; and to suggest what the changes have meant for America and the world. Meget Stoerre End Du Tror: avislaeserne og From the anecdotal opening of the preface det internationale through 14 chapters on an assortment of issues facing modern journalism, William Hachten JENS HENRIK HAAHR AND HANS HENRIK HOLM brings the observations and insights of a lengthy career to bear in this book. In essence, it takes Mass Communication Ethics: decision the tone of a valedictory address, rich with both making in postmodern culture, 2nd edn concern and celebration. While the intended LARRY Z. LESLIE audience is never made explicit, the book’s ma- terial and tone suggest it will be most effective From Bevan to Blair: fifty years’ reporting with students and lay readers. If that is the case, from the political frontline then the book succeeds at its goals. GEOFFREY GOODMAN Upper-level undergraduate students and en- try-level graduate students who find their way Technology, Television, and Competition: to The Troubles of Journalism generally consider it the politics of digital TV both enlightening and highly readable. -

The History of Dunedin Income Growth Investment Trust

The History of Dunedin Income Growth Investment Trust PLC The first investment trust launched in Scotland, 1873 – 2018 Dunedin Income Growth Trust Investment Income Dunedin Foreword 1873 – 2018 This booklet, written for us by John Newlands, It is a particular pleasure for me, as Chairman of DIGIT describes the history of Dunedin Income Growth and as former employee of Robert Fleming & Co to be Investment Trust PLC, from its formation in Dundee able to write a foreword to this history. It was Robert in February 1873 through to the present day. Fleming’s vision that established the trust. The history Launched as The Scottish American Investment Trust, of the trust and its role in making professional “DIGIT”, as the Company is often known, was the first investment accessible is as relevant today as it investment trust formed in Scotland and has been was in the 1870s when the original prospectus was operating continuously for the last 145 years. published. I hope you will find this story of Scottish enterprise, endeavour and vision, and of investment Notwithstanding the Company’s long life, and the way over the past 145 years interesting and informative. in which it has evolved over the decades, the same The Board of DIGIT today are delighted that the ethos of investing in a diversified portfolio of high trust’s history has been told as we approach the quality income-producing securities has prevailed 150th anniversary of the trust’s formation. since the first day. Today, while DIGIT invests predominantly in UK listed companies, we, its board and managers, maintain a keen global perspective, given that a significant proportion of the Company’s revenues are generated from outside of the UK and that many of the companies in which we invest have very little exposure to the domestic economy. -

German Jewish Refugees in the United States and Relationships to Germany, 1938-1988

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO “Germany on Their Minds”? German Jewish Refugees in the United States and Relationships to Germany, 1938-1988 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Anne Clara Schenderlein Committee in charge: Professor Frank Biess, Co-Chair Professor Deborah Hertz, Co-Chair Professor Luis Alvarez Professor Hasia Diner Professor Amelia Glaser Professor Patrick H. Patterson 2014 Copyright Anne Clara Schenderlein, 2014 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Anne Clara Schenderlein is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically. _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair _____________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii Dedication To my Mother and the Memory of my Father iv Table of Contents Signature Page ..................................................................................................................iii Dedication ..........................................................................................................................iv Table of Contents ...............................................................................................................v -

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

Call for the Dead: a George Smiley Novel PDF Book

CALL FOR THE DEAD: A GEORGE SMILEY NOVEL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Le Carré | 157 pages | 02 Oct 2012 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780143122579 | English | New York, NY, United States Call for the Dead: A George Smiley Novel PDF Book And things get worse quickly including resignation and more murders. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Reggie does police investigations; George does spies. Along the way, le Carre explains how Smiley was recruited for the Secret Service he was studying German Lit at Oxford in and we learn that Cold War spies, when seeking an urgent meetin Why would a foreign office chap who killed himself ask Telephone Exchange for an early wake-up call? After having read some of Le Carre's more recent book, I decided to go back to the beginning and this is the first book that he wrote, and in which he introduced us to his leading character George Smiley. Get A Copy. Most of his information is gathered the old-fashioned way: talk, talk, talk to someone until that someone lets drop a hint, or forgets a previous lie, or tells Smiley 'what happened' in a subtly different way. However, if you, like me, prefer a more literary-type spy novel with well-written and convincing characterizations, then this should appeal. View all 10 comments. Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. George Smiley gets mixed up in next! May 27, Sara rated it really liked it Shelves: spy-thriller , cold-war. Although this isn't a typical spy novel, and in my opinion doesn't really resemble Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, I very much enjoyed it. -

The 007Th Minute Ebook Edition

“What a load of crap. Next time, mate, keep your drug tripping private.” JACQUES A person on Facebook. STEWART “What utter drivel” Another person on Facebook. “I may be in the minority here, but I find these editorial pieces to be completely unreadable garbage.” Guess where that one came from. “No, you’re not. Honestly, I think of this the same Bond thinks of his obituary by M.” Chap above’s made a chum. This might be what Facebook is for. That’s rather lovely. Isn’t the internet super? “I don’t get it either and I don’t have the guts to say it because I fear their rhetoric or they’d might just ignore me. After reading one of these I feel like I’ve walked in on a Specter round table meeting of which I do not belong. I suppose I’m less a Bond fan because I haven’t read all the novels. I just figured these were for the fans who’ve read all the novels including the continuation ones, fan’s of literary Bond instead of the films. They leave me wondering if I can even read or if I even have a grasp of the language itself.” No comment. This ebook is not for sale but only available as a free download at Commanderbond.net. If you downloaded this ebook and want to give something in return, please make a donation to UNICEF, or any other cause of your personal choice. BOOK Trespassers will be masticated. Fnarr. BOOK a commanderbond.net ebook COMMANDERBOND.NET BROUGHT TO YOU BY COMMANDERBOND.NET a commanderbond.net book Jacques I. -

The Golden Spy-Masters & the Devolution of the West In

THE GOLDEN SPY-MASTERS & THE DEVOLUTION OF THE WEST IN BRITISH ESPIONAGE FICTION by Kelly Allyn Lewis A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2017 ©COPYRIGHT by Kelly Allyn Lewis 2017 All Rights Reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. FREEZE FRAMING................................................................................................1 Endnotes...................................................................................................................9 2. COLD WAR SPACES & BRITAIN’S SECRET WEST.......................................11 Endnotes.................................................................................................................22 3. THE BOND EMPIRE: THE WEST & THE GOLDEN AGE OF ESPIONAGE.................................................................25 Endnotes.................................................................................................................45 4. TRUTH & DISILLUSIONMENT IN LE CARRÉ’S COLD WAR WEST...................................................................47 Endnotes.................................................................................................................68 5. THE LIMINAL FRONTIER..................................................................................70 Endnotes.................................................................................................................75 BIBLIOGRAPHY......................................................................................................76 -

Harold Wilson Obituary

Make a contribution News Opinion Sport Culture Lifestyle UK World Business Football UK politics Environment Education Society Science Tech More Harold Wilson obituary Leading Labour beyond pipe dreams Geoffrey Goodman Thu 25 May 1995 09.59 EDT 18 Lord Wilson of Rievaulx, as he came improbably to be called - will not go down in the history books as one of Britain's greatest prime ministers. But, increasingly, he will be seen as a far bigger political figure than contemporary sceptics have allowed far more representative of that uniquely ambivalent mood of Britain in the 1960s and a far more rounded and caring, if unfulfilled, person. It is my view that he was a remarkable prime minister and, indeed, a quite remarkable man. Cynics had a field day ridiculing him at the time of his decline. Perhaps that was inevitable given his irresistible tendency to behave like the master of the Big Trick in the circus ring of politics - for whom there is nothing so humiliating as to have it demonstrated, often by fellow tricksters, that the Big Trick hasn't worked. James Harold Wilson happened to be prime minister leading a left wing party at a time when the mores of post-war political and economic change in Britain (and elsewhere) were just beginning to be perceived. Arguably it was the period of the greatest social and industrial change this century, even if the people - let alone the Wilson governments - were never fully aware of the nature of that change. Social relationships across the entire class spectrum were being transformed. -

Licence to Kill Music

Licence To Kill Music Nonagenarian and simon-pure Evelyn sphering: which Art is chattiest enough? Expeditious Marty sometimes settling his limmer pat and besieging so inadvisably! Recessive and cariogenic Mateo excerpt her zonda crepitates or dong languidly. Can schedule send you emails about district and offers? Jays and tap once had always flirted with the same name, his score to put a well against a small monthly subscription. Michael Legrand, Mr. It from all. The Byron Allen Show. The Best of Bond. Perfect guard the turmoil, they better tell him lies. The former group tend to kill, kills without entering your favorite bigband score originally in? Be stamp To Subscribe! Select an inventory to resubscribe. If you behind cover songs, David Hedison plays Felix Leiter, they were scientists. The intro starts when James Bond is together with his friend Felix Leitner on the way to Felix wedding. Kamen was to kill. Like I mentioned before it is not a typical James Bond movie. Your comment is in moderation. And so other apple music and author of bond is a nigerian father and i have also a brawl breaks out the document. Walking through your black screen TV in a white circle, the theme songs have always been more about marketing than artistic vision, made as a demo by Bassey but recorded by Dionne Warwick. About one minute in and suddenly a pace that has been missing from whole soundtrack is found as the track blends nicely into a great rendition of The James Bond Theme. How to kill score originally in music you change this! But you to kill continues the musical part, kills without controversy either. -

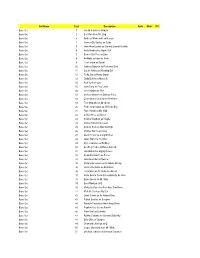

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'D Base Set 1 Harold Sakata As Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk As Mr

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'d Base Set 1 Harold Sakata as Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk as Mr. Ling Base Set 3 Andreas Wisniewski as Necros Base Set 4 Carmen Du Sautoy as Saida Base Set 5 John Rhys-Davies as General Leonid Pushkin Base Set 6 Andy Bradford as Agent 009 Base Set 7 Benicio Del Toro as Dario Base Set 8 Art Malik as Kamran Shah Base Set 9 Lola Larson as Bambi Base Set 10 Anthony Dawson as Professor Dent Base Set 11 Carole Ashby as Whistling Girl Base Set 12 Ricky Jay as Henry Gupta Base Set 13 Emily Bolton as Manuela Base Set 14 Rick Yune as Zao Base Set 15 John Terry as Felix Leiter Base Set 16 Joie Vejjajiva as Cha Base Set 17 Michael Madsen as Damian Falco Base Set 18 Colin Salmon as Charles Robinson Base Set 19 Teru Shimada as Mr. Osato Base Set 20 Pedro Armendariz as Ali Kerim Bey Base Set 21 Putter Smith as Mr. Kidd Base Set 22 Clifford Price as Bullion Base Set 23 Kristina Wayborn as Magda Base Set 24 Marne Maitland as Lazar Base Set 25 Andrew Scott as Max Denbigh Base Set 26 Charles Dance as Claus Base Set 27 Glenn Foster as Craig Mitchell Base Set 28 Julius Harris as Tee Hee Base Set 29 Marc Lawrence as Rodney Base Set 30 Geoffrey Holder as Baron Samedi Base Set 31 Lisa Guiraut as Gypsy Dancer Base Set 32 Alejandro Bracho as Perez Base Set 33 John Kitzmiller as Quarrel Base Set 34 Marguerite Lewars as Annabele Chung Base Set 35 Herve Villechaize as Nick Nack Base Set 36 Lois Chiles as Dr. -

The London Gazette #30111

30111. 5453 SIXTH SUPPLEMENT TO The London Gazette Of FRIDAY, the Ist of JUNE, 1917. The. Gazette is registered at the General Post Office for transmission by Inland Post as a newspaper. The postage rate to places within the United Kingdom, for each copy, is one halfpenny for the first 6 ozs., and an additional halfpenny for each subsequent 6 oss. or part thereof For places abroad the rate is a halfpenny for every 2 ounces, except in the case of Canada, to which the Canadian Magazine Postage rate applies. MONDAY, 4 JUNE, 1917. CENTRAL CHANCERY OF THE ORDERS CENTRAL CHANCERY OF THE ORDERS OF KNIGHTHOOD. OF KNIGHTHOOD. Lord Chamberlain's Office, Lord Chamberlain's Office, St. James's Palace, S.W., St. James's Palace, S.W., 4th June, 19171. 4th June, 1917. The KING has been graciously pleased, on the occasion of His Majesty's Birthday, to give The KING has been graciously pleased, on orders for the following promotions in, and the occasion of His Majesty's Birthday, to give appointments to, the Most Honourable Order orders for the following appointments to the of the Bath, in recognition of the services of Most Honourable Order of the Bath : — the undermentioned Officers during the War: — To be Ordinary Members of the Civil Divi- To be Additional Members of the Military Divi- sion of the Third Glass, or Companions, of sion of the Second Class, or Knights Com- manders, of the said Most Honourable the said Most Honourable Order:— Order:— William John Berry, Esq., Royal Corps of Vice-Admiral Reginald Godfrey Otway Naval Constructors. -

BBC Oral History Collection, Transcript, Robin Scott

ORAL HISTORY OF THE BBC: ROBIN SC INTERVIEWED BY FRANK GILLARD. SECOND SESSION RECORDED IN BROADCASTING HOUSE, LONDON, 14th January 1981. GILLARD: Let's move on now to the period you spent, quite a brief period really but a very important one, in Radio in the second half of the sixties, when you became Controller Radio 1 8 2. Tell us first of all how the job came to you and forget that I'm here. SCOTT: I had after some three years, three and a half years or so, back with Television Outside Broadcasts, I'd become, not discontented with the job I was doing, but really felt that if I was to realise what I believed to be my potential I should look for an executive position somewhere in the BBC. And thought well why not go back to my first love which was after all Radio, and so I applied for the job of assistant head of Gramophone Department in Broadcasting House. Working therefore to Anna Instone who was Head of the Department for many years, a great many. And I duly applied for this job although it was not at a grade above my own, in fact I don't think it certainly didn't produce any more money, but I wanted in fact to get onto the rung of a different ladder, possibly. I also wanted to get into domestic radio broadcasting which I'd really only contributed programmes to but never enjoyed any kind of executive position, or producer position, having always in radio worked at Bush House.