A Novel and "Time, Self and Metaphor in Illness Stories": an Exegesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Jazz Still Matters Jazz Still Matters Why Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Journal of the American Academy

Dædalus Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Spring 2019 Why Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, guest editors with Farah Jasmine Griffin Gabriel Solis · Christopher J. Wells Kelsey A. K. Klotz · Judith Tick Krin Gabbard · Carol A. Muller Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences “Why Jazz Still Matters” Volume 148, Number 2; Spring 2019 Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, Guest Editors Phyllis S. Bendell, Managing Editor and Director of Publications Peter Walton, Associate Editor Heather M. Struntz, Assistant Editor Committee on Studies and Publications John Mark Hansen, Chair; Rosina Bierbaum, Johanna Drucker, Gerald Early, Carol Gluck, Linda Greenhouse, John Hildebrand, Philip Khoury, Arthur Kleinman, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, Alan I. Leshner, Rose McDermott, Michael S. McPherson, Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Scott D. Sagan, Nancy C. Andrews (ex officio), David W. Oxtoby (ex officio), Diane P. Wood (ex officio) Inside front cover: Pianist Geri Allen. Photograph by Arne Reimer, provided by Ora Harris. © by Ross Clayton Productions. Contents 5 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson 13 Following Geri’s Lead Farah Jasmine Griffin 23 Soul, Afrofuturism & the Timeliness of Contemporary Jazz Fusions Gabriel Solis 36 “You Can’t Dance to It”: Jazz Music and Its Choreographies of Listening Christopher J. Wells 52 Dave Brubeck’s Southern Strategy Kelsey A. K. Klotz 67 Keith Jarrett, Miscegenation & the Rise of the European Sensibility in Jazz in the 1970s Gerald Early 83 Ella Fitzgerald & “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Berlin 1968: Paying Homage to & Signifying on Soul Music Judith Tick 92 La La Land Is a Hit, but Is It Good for Jazz? Krin Gabbard 104 Yusef Lateef’s Autophysiopsychic Quest Ingrid Monson 115 Why Jazz? South Africa 2019 Carol A. -

Thursday, July 7, 2016 Email: [email protected] Vol

4040 yearsyears ofof coveringcovering SouthSouth BeltBelt Voice of Community-Minded People since 1976 Thursday, July 7, 2016 Email: [email protected] www.southbeltleader.com Vol. 41, No. 23 Vacation photos sought The Leader is seeking readers’ 2016 vaca- Hughes Road construction causes headaches tion photos for possible publication. A first- and second-place prize of Schlitterbahn tickets Construction work along Hughes Road con- least one shop owner has temporarily shuttered tomobile accidents at the corner of Beamer and vide key upgrades such as water lines, sanitary will be awarded monthly during June, July and tinues to irk local residents and business owners, his doors until the traffi c situation improves. Hughes. While the offi cial number of collisions sewers, new concrete pavement, sidewalks and August to the best submissions. Each month’s who say the project is causing widespread confu- The Leader has put a request in to the City of was unavailable at press time Wednesday, the curbs, street lighting, traffi c control and new sig- first-place winner will be awarded eight tick- sion and traffi c congestion. Houston Public Works and Engineering Depart- Leader has heard from multiple Houston police nage. ets, while each month’s second-place winner A primary concern is the added traffi c when ment to see if the signals can be adjusted at the offi cers that at least one crash takes place per day Despite all of the current issues, construction will be awarded six. traveling north on Beamer toward Hughes from intersection to improve traffi c fl ow. According to at the intersection – some of which are serious in is reportedly on schedule and set to be complete All submissions should include where and Scarsdale. -

HEROES and HOPE 2021 KWAME SIMMONS Founder the Simmons Advantage

HEROES AND HOPE 2021 KWAME SIMMONS Founder The Simmons Advantage A 2015 BET Honors Award recipient and an invited guest to the White House during the Obama administration, Kwame Simmons is a change agent for inner-city schools. With a twenty-year stellar career in education, he has worked tirelessly for students in the nation’s capital and the St. Louis school system. Now, Simmons has brought his knowledge to his hometown to assist with improving the Detroit schools as a consultant. Simmons uses untapped data on how minority students learn to help them succeed in revolutionary ways. “What I’ve tried to do is provide schools with the tools they need to succeed, offering new perspectives to identify their specific challenges.” This year Simmons plans to equip special education students with tools to gain tech jobs and introduce students to coding and gaming as viable career options. JANUARY 2021 SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY NEW YEAR’S DAY MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. DAY INTERNATIONAL DAY OF EDUCATION TRESA GALLOWAY CEO Love Laces As an educator and mother, Tresa Galloway has seen first-hand what happens when children are labeled as having ‘special needs’. When her son was bullied, Galloway prayed for the tools to allow him to handle the bully on his own. That’s when Love Laces was born. Love Laces is a shoelace brand that prints positive affirmations on colorful laces for victims of bullying and low self-esteem. Once labeled as too emotional, Galloway has channeled those emotions to help others. She says, “When you’re faced with fear, you have to come up with strategies on overcoming those fears.” Thanks to her, when a child looks down, they have a reason to look up and know they are loved. -

Complete Book of Necromancers by Steve Kurtz

2151 ® ¥DUNGEON MASTER® Rules Supplement Guide The Complete Book of Necromancers By Steve Kurtz ª Table of Contents Introduction Bodily Afflictions How to Use This Book Insanity and Madness Necromancy and the PC Unholy Compulsions What You Will Need Paid In Full Chapter 1: Necromancers Chapter 4: The Dark Art The Standard Necromancer Spell Selection for the Wizard Ability Scores Criminal or Black Necromancy Race Gray or Neutral Necromancy Experience Level Advancement Benign or White Necromancy Spells New Wizard Spells Spell Restrictions 1st-Level Spells Magic Item Restrictions 2nd-Level Spells Proficiencies 3rd-Level Spells New Necromancer Wizard Kits 4th-Level Spells Archetypal Necromancer 5th-Level Spells Anatomist 6th-Level Spells Deathslayer 7th-Level Spells Philosopher 8th-Level Spells Undead Master 9th-Level Spells Other Necromancer Kits Chapter 5: Death Priests Witch Necromantic Priesthoods Ghul Lord The God of the Dead New Nonweapon Proficiencies The Goddess of Murder Anatomy The God of Pestilence Necrology The God of Suffering Netherworld Knowledge The Lord of Undead Spirit Lore Other Priestly Resources Venom Handling Chapter 6: The Priest Sphere Chapter 2: Dark Gifts New Priest Spells Dual-Classed Characters 1st-Level Spells Fighter/Necromancer 2nd-Level Spells Thief / Necromancer 3rd-Level Spells Cleric/Necromancer 4th-Level Spells Psionicist/Necromancer 5th-Level Spells Wild Talents 6th-Level Spells Vile Pacts and Dark Gifts 7th-Level Spells Nonhuman Necromancers Chapter 7: Allies Humanoid Necromancers Apprentices Drow Necromancers -

Victims, Heroes, Survivors: Sexual Violence on the Eastern Front

VICTIMS, HEROES, SURVIVORS SEXUAL VIOLENCE ON THE EASTERN FRONT DURING WORLD WAR II A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Wendy Jo Gertjejanssen IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Eric D. Weitz May 2004 Copyright © Wendy Jo Gertjejanssen 2004 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to all of the people on my committee, some of whom have given me inspiration and gracious support for many years: Lisa Albrecht, David Good, Mary Jo Maynes, Rick McCormick, Eric Weitz, and Tom Wolfe. Thank you to Theofanis Stavrou who was supportive in many ways during my early years of graduate school. I would also like to thank the following scholars who have helped me in various ways: David Weissbrodt, John Kim Munholland, Gerhard Weinberg, Karel Berkhoff, Kathleen Laughlin, and Stephen Feinstein. A special thank you to Hannah Schissler, who in addition to other kinds of support introduced me to the scholarly work on rape during World War II. I would like to express my gratitude for the funding I have received: Grant for Study Abroad and Special Dissertation Grant (the University of Minnesota, Summer 1998); Travel Grant (University of Minnesota History Department, Summer 1998); Short-term Research Grant (DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service) Summer 1998. In the fall of 2002 I was a fellow at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum on behalf of the Charles H. Revson Foundation, and I would like to thank all of the staff at the Center of Advanced Holocaust Studies at the museum for pointing me to sources and helping in other ways, including Martin Dean, Wendy Lower, Sharon Muller, and Alex Rossino. -

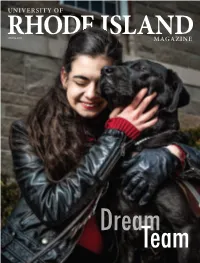

2019-Spring-URI-Magazine.Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF RHODESPRING 2019 ISLANDMAGAZINE Dream Team Aperture “NIZAM ZACHMAN FISHING PORT, JAKARTA, INDONESIA” by Fery Sutyawan, Ph.D. ’19 Fery Sutyawan took this photo in summer 2017, when he did a field observation at Nizam Zachman for his dissertation research. The fishing port is the largest in Indonesia, home to more than 1,200 industrial-scale fishing vessels. Indonesia is the second largest marine fisheries producer in the world, and there is not enough port space to accommodate the country’s fishing boats. URI is involved in numerous projects and partnerships with Indonesia, most of which relate to fisheries, marine affairs, and sustainable development. Sutyawan explains that this photo depicts the strength of the country’s fishing fleet, while also illustrating the problem of increasing global exploitation of fisheries resources. This spring, Sutyawan will defend his dissertation, which focuses on marine fisheries governance in Indonesia. UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND MAGAZINE Inside UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND MAGAZINE • VOL. 1, NO. 2 • SPRING 2019 4 FROM THE PRESIDENT 6 FEEDBACK FEATURES 18 34 CURRENTS QUANTUM QUEST GROWING A CURE 8 Entrepreneur Christopher URI’s medicinal gardens DIDN’T READ Savoie ’92 has his sights are a unique resource for MOBY-DICK? set on the revolutionary faculty and students. potential of quantum They are integral to URI’s Real-life ways to catch computing. It could lead prominence in natural up—and why you should. to more efficient fuel, products research. advances in drug 9 discovery, and maybe 38 QUAD ANGLES even cleaner air. A PERFECT FIT NETWORK Ben Leveillee on 25 Kunal Mankodiya and his 46 exploring space and time. -

A God Why Is Hermes Hungry?1

CHAPTER FOUR A GOD WHY IS HERMES HUNGRY?1 Ἀλλὰ ξύνοικον, πρὸς θεῶν, δέξασθέ με. (But by the gods, accept me as house-mate) Ar. Plut 1147 1. Hungry Hermes and Greedy Interpreters In the evening of the first day of his life baby Hermes felt hungry, or, more precisely, as the Homeric Hymn to Hermes in which the god’s earliest exploits are recorded, says, “he was hankering after flesh” (κρειῶν ἐρατίζων, 64). This expression reveals only the first of a long series of riddles that will haunt the interpreter on his slippery journey through the hymn. After all, craving for flesh carries overtly negative connotations.2 In the Homeric idiom, for instance, the expression is exclusively used as a predicate of unpleasant lions.3 Nor does it 1 This chapter had been completed and was in the course of preparation for the press when I first set eyes on the important and innovative study of theHymn to Hermes by D. Jaillard, Configurations d’Hermès. Une “théogonie hermaïque”(Kernos Suppl. 17, Liège 2007). Despite many points of agreement, both the objectives and the results of my study widely diverge from those of Jaillard. The basic difference between our views on the sacrificial scene in the Hymn (which regards only a section of my present chapter on Hermes) is that in the view of Jaillard Hermes is a god “who sac- rifices as a god” (“un dieu qui sacrifie en tant que dieu,” p. 161; “Le dieu n’est donc, à aucun moment de l’Hymne, réellement assimilable à un sacrificateur humain,” p. -

Voices in the Hall: Buddy and Julie Miller Episode Transcript

VOICES IN THE HALL: BUDDY AND JULIE MILLER EPISODE TRANSCRIPT PETER COOPER Welcome to Voices in the Hall, presented by the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. I’m Peter Cooper. My guests today are two remarkable musicians… Buddy and Julie Miller. BUDDY MILLER We only moved here for economics. Just to maybe we could talk ourselves into a house because musicians are almost people in Nashville. In L.A., anywhere else we were living it's like no way a musician’s going to end up with a house. We were broke and just seemed like we were going to be. So we moved here. JULIE MILLER We were kind of fine with being broke. BUDDY MILLER Yeah. We were always fine with being broke. But we got here and we found out this is a great city with so many, there's so much going on here musically,. JULIE MILLER More and more. BUDDY MILLER Yeah. And we just fell in with like-minded music friends. JULIE MILLER Buddy would go to sleep at a reasonable hour, and I would stay up all night ‘til the sun would come up. Once I got done with this song that night, smiled and I said, “Buddy, I’ve got you a song.” PETER COOPER It’s Voices in the Hall with Buddy and Julie Miller. “Breakdown on 20th Avenue South” Buddy & Julie Miller (Title Track / New West) PETER COOPER “Breakdown on 20th Avenue South.” Now, 20th Avenue South is a lovely residential street, located within walking distance — if you’re up for walking — of a pretty good grocery store and Brown’s Diner, where many of Nashville’s finest songwriters go to hang out and talk about most anything but songwriting. -

Harold MABERN: Teo MACERO

This discography is automatically generated by The JazzOmat Database System written by Thomas Wagner For private use only! ------------------------------------------ Harold MABERN: "Workin' And Wailin'" Virgil Jones -tp,flh; George Coleman -ts; Harold Mabern -p; Buster Williams -b; Leo Morris -d; recorded June 30, 1969 in New York Leo Morris aka Idris Muhammad 101615 A TIME FOR LOVE 4.54 Prest PR7687 101616 WALTZING WESTWARD 9.26 --- 101617 I CAN'T UNDERSTAND WHAT I SEE IN YOU 8.33 --- 101618 STROZIER'S MODE 7.58 --- 101619 BLUES FOR PHINEAS 5.11 --- "Greasy Kid Stuff" Lee Morgan -tp; Hubert Laws -fl,ts; Harold Mabern -p; Boogaloo Joe Jones -g; Buster Williams -b; Idriss Muhammad -d; recorded January 26, 1970 in New York 101620 I WANT YOU BACK 5.30 Prest PR7764 101621 GREASY KID STUFF 8.23 --- 101622 ALEX THE GREAT 7.20 --- 101623 XKE 6.52 --- 101624 JOHN NEELY - BEAUTIFUL PEOPLE 8.33 --- 101625 I HAVEN'T GOT ANYTHING BETTER TO DO 6.04 --- "Remy Martin's New Years Special" James Moody Trio: Harold Mabern -p; Todd Coleman -b; Edward Gladden -d; recorded December 31, 1984 in Sweet Basil, New York it's the rhythm section of James Moody Quartet 99565 YOU DON'T KNOW WHAT LOVE IS 13.59 Aircheck 99566 THERE'S NO GREEATER LOVE 10.14 --- 99567 ALL BLUES 11.54 --- 99568 STRIKE UP THE BAND 13.05 --- "Lookin' On The Bright Side" Harold Mabern -p; Christian McBride -b; Jack DeJohnette -d; recorded February and March 1993 in New York 87461 LOOK ON THE BRIGHT SIDE 5.37 DIW 614 87462 MOMENT'S NOTICE 5.25 --- 87463 BIG TIME COOPER 8.04 --- 87464 AU PRIVAVE -

Troops Severely Disabled in War on Terror Thank Coalition Donors for 10 Years of Help

® Volume 46 H April 2014 Providing Emergency Aid to Troops Severely Disabled in the War on Terror Troops severely disabled in war on terror “ thank Coalition donors for 10 years of help It’s not about the money or gifts, but about the selfless Sometimes a picture says more than educational conference, several wounded donors who work to keep a thousand words. This is one of those heroes found a creative way to say thank you “ times. for sending them to this life-changing event. the Coalition going. The heartwarming photo above was As you can see, your support is — Wife of wounded hero taken at the Coalition’s 2013 Road to making a real impact. Recovery Conference in Orlando, Florida, And the upcoming Memorial Day which was attended by nearly 100 severely holiday is the perfect time to celebrate all disabled troops and their families. we’ve done together since the Coalition And on the final night of the four-day was founded 10 years ago, in 2004. Inside your Road to Recovery Report: Letter from President 2004-2014: 10 Years of Helping Double Amputee Rob Jones David Walker America’s Disabled Heroes Rides Bike Across Country page 2 pages 8-9 page 15 Donors Rescue Wounded Coalition Donors a “Godsend” Thank You Letters from Hero and Son for a Wounded Hero Grateful Veterans page 5 page 13 page 16 Coalition to Salute America’s Heroes ★ PO Box 96440 ★ Washington, DC 20090-6440 ★ www.saluteheroes.org ★ 1-888-447-2588 Letter from President David Walker Dear Friend of Our Wounded Heroes, I’m pleased to share with you this issue of The Road to Recovery Report – the Coalition’s newsletter highlighting how we’re putting your donations to work to combat the frightening crises facing our severely disabled military service members today. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

The Trail, 2009-10-09

October 9, 2009 • Volume 99, Issue 3 CIVIL RIGHTS AT STAKE Students, alumni come together for Homecoming 2009 By HANNAH KITZROW For the first time in over 35 years, Homecoming Weekend and Family Weekend will be combined into one. Events for both family and alumni will take place the weekend of Oct. 9. “ASUPS is going all-out for stu- dents during Homecoming Week and Homecoming and Family Weekend to bring new change. One complaint students have had about Homecoming is that it wasn’t fo- cused enough on the students. This year we’re trying to put that fo- cus back on students,” James Luu, ASUPS President, said. “This year is the first time we’ve combined two fall weekend events into one ” said Rebecca Harrison, the Assistant Director for Alumni and Parent Relations. “Homecom- ing, which was mostly for students, alumni and the campus community, and Fall Family Weekend, which fo- cused on students and parents.” The weekend kicks off with the President’s Welcome Reception Fri- day at 5:30 p.m. All family members and students are welcome to this event at Presi- dent Ron Thomas’ house. The same night there is also a BBQ sponsored by ASUPS and SAA starting at 6 p.m. At 9 p.m., the group Blues Schol- ars will be performing for students in the S.U.B. Legislating Love “Blues Scholars performed at my high school a few years ago, and were amazing. I can’t wait for them Referendum 71 reevaluates the nature of domestic to come to campus; it’s going to be an awesome show,” freshman Anna partnerships in the state of Washington.