The Application of the Exodus Divine-Presence Narratives As a Biblical Socio-Ethical Paradigm for the Contemporary Redeemed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Islamochristiana

PONTIFICIO ISTITUTO DI STUD1 ARAB1 E D'ISLAMISTICA ISLAMOCHRISTIANA (ESTRATTO) MUHIB 0. OPELOYE CONFLUENCE AND CONFLICT IN THE QUR'ANIC AND BIBLICAL ACCOUNTS OF THE LIFE OF PROPHET MUSA 1990 ROMA MUHIB 0. OPELOYE * CONFLUENCE AND CONFLICT IN THE QUR'ANIC AND BIBLICAL ACCOUNTS OF THE LIFE OF PROPHET MOSA SUMMARY:The A. compares the qur'inic and biblical presentations of Moses. Though the Qur'in does not set out the prophet's life chronologically, a chronological account can be constructed from the various passages. It can be seen that this is very similar to the life of Moses as told by the Bible. The A. nevertheless lists seven points of dissimilarity. These he attributes to the different circumstances in which the message was recorded. The similarities, he suggests, indicate a common source and origin. Prophet Miisii (the Biblical Moses), otherwise known as Kalimu Iliihz, is the only prophet of God, apart from prophet Yiisuf, whose life account is given in detail by the Qur'Zn. Information on his life is mainly contained in Siirat al-Baqarah (2:49-71); Siirat al-A 'rcTf (7:10&162); Siirat Tiihi (20:9-97); Siirat ash-Shu'arii' (26:10-69) and SGrat al-Qi~a:r. (28:342), apart from other Qur'iinic passages where casual references are made to different aspects of his life. The special attention given to MiisZ by the Qur'iin derives perhaps from * Dr Muhib 0. Opeloye (born 1949) holds a Ph.D. in Islamic Studies from the University of Ilorin, Nigeria. For his thesis he presented A Comparative Study of Selected SocieTheolo~~ical Themes Common to the Qur'in and the Bible. -

Divine Manifestations in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha Orientalia Judaica Christiana

Divine Manifestations in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha Orientalia Judaica Christiana 2 Orientalia Judaica Christiana, the Christian Orient and its Jewish Heritage, is dedicated, first of all, to the afterlife of the Jewish Second Temple traditions within the traditions of the Christian East. A second area of exploration is some priestly (non-Talmudic) Jewish traditions that survived in the Christian environment Divine Manifestations in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha Andrei Orlov govg'ms press 2009 For law and June Fair ... Then the old man stood up and stretched his hands to wards heaven. His fingers became like ten lamps of fire and he said to him, "If you will, you can become all flame/5 Apophthegmata Patrum, Joseph of Panephysis, 7. Abba Bessarion, at the point of death, said, "The monk ought to be as the Cherubim and the Seraphim: all eye." Apophthegmata Patrum, Bessarion, 11. TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface xv Locations of the Original Publications xvii List of Abbreviations xix INTRODUCTION. The Kavod and Shem Paradigms and Divine Manifestations in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha 1 Silvanus and Anthony. 3 Moses and Elijah 8 Enoch and Abraham 12 PART I: THE DIVINE BODY TRADITIONS 19 "Without Measure and Without Analogy": The Tradition of the Divine Body in 2 (Slavonic) Enoch 21 Introduction 21 Adamic Tradition of 2 Enoch 23 The Corporeality of the Protoplast 26 From the Four Corners of the World 29 The Measure of the Divine Body. 34 Bodily Ascent 37 Adam and Enoch: "Two Powers" in Heaven 38 Two Bodies Created According to the Likeness of the Third One 43 The Pillar of the World: The Eschatological Role of the Seventh Antediluvian Hero in 2 (Slavonic) Enoch 49 Introduction 49 I. -

Propaganda and Polemical Works Targeting -E E �= Muslims and Jews, Lnquisition Records, and Christian and Muslim Sermons

ur.e Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona Serveide Publicacions Cándida Ferrero Hernández, has been conducting research at the Autonomous University ¡,¡ e: e: of Barcelona since 2000; in 2016 she received the Advanced Research Accreditation o 111 (Full Professor) from AQU-Catalonia. Since 2000, she has been a member (currently PI) E ! of lslamolatina, a group dedicated to the study of the cultural and religious relations 111cii ... E of the Latin world with Islam, paying particular attention to Latin translations of Arabic "'C� texts on lslamic doctrine. e:·- 111] G. Jones :íl� Linda is a Tenured Associate Professor at the Pompeu Fabra University in -� E Barcelona. She is a historian of religions specializing in lslamic Studies; the religious 111 CU cultures and Muslim-Christian relations of medieval lslamic Iberia and the Maghreb �"'C (12th-15th ..... o c); medieval lslamic preaching and oratory; and gender and masculinity in ·e: E medieval Islam. - cu cu111 ... c. :E cu .......... .e: The eleven essays included in this collective vol u me examine a range of textual genres e: ·- produced by Christians and Muslims throughout the Mediterranean, including materials �-=111 from the Corpus lslamolatinum, Christian propaganda and polemical works targeting -e E �= Muslims and Jews, lnquisition records, and Christian and Muslim sermons. Despite the CU 111 diversity of the works under consideration and the variety of methodological and >::, disciplinary approaches employed in their analysis, the volume is bound together by 8� ...... "C the common goals of exploring the propaganda strategies premodern authors deployed e: e: 2.111 for specific aims, be it the unification of religious, cultural, and political groups through "C discourses of self-representation, or the invention of the political, cultural, religious, .,¡ or gendered other. -

Download the Origins of the Druze People and Religion Free Ebook

THE ORIGINS OF THE DRUZE PEOPLE AND RELIGION DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Philip K Hitti | 100 pages | 29 May 2008 | BiblioLife | 9781434685377 | English | Charleston SC, United States Who are the Druze and How Might the Shroud of Turin Relate Them to Jesus Christ? Paperbackpages. Religion and society. Some scholars maintain that Israel has tried to separate the Druze from other Arab communities, and that the effort has influenced the way Israel's Druze perceive their modern identity. View 2 comments. No trivia or quizzes yet. InHamza officially revealed the Druze faith and began to preach the Unitarian doctrine. At the end of the 17th century the Shihabs succeeded the Ma'ans in the feudal leadership of Druze southern Lebanon, although they reportedly professed Sunni Islam, they showed sympathy with Druzism, the religion of the majority of their subjects. The conquest of Syria by the Muslim Arabs in the middle of the seventh century introduced into the land two political factions later called the Qaysites and the Yemenites. An analysis of this situation which sees Druze ethnicity simply as an internally generated product of Druze history and culture, or as a product of some independent Druze strategy, and which ignores the nature of the Israeli State, is bound to obscure the latter's manipulative role in the generation of political consciousness. On account of this, orthodox Islam never hesitated to exclude Druzism from its fold. And, of course, with an ethnie as pronounced as that of the Druzes, there was from the start a ready "core" that could be made use of and a plethora of "givens" in which to embed new "invented traditions". -

Proquest Dissertations

Reincarnation, marriage, and memory: Negotiating sectarian identity among the Druze of Syria Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Bennett, Marjorie Anne, 1963- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 10:45:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/283987 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. -

Intimate Bodies, Violent Struggles the Poetics And

Durham E-Theses Intimate Bodies, Violent Struggles: The poetics and politics of nuptiality in Syria KASTRINOU, A. MARIA A. How to cite: KASTRINOU, A. MARIA A. (2012) Intimate Bodies, Violent Struggles: The poetics and politics of nuptiality in Syria , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4923/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Intimate Bodies, Violent Struggles The poetics and politics of nuptiality in Syria A. Maria A. Kastrinou Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology Durham University 2012 Abstract Intimate bodies, violent struggles: The poetics and politics of nuptiality in Syria Caught between conflicting historical fantasies of an exotic Orient and images of the oppressive and threatening Other, Syria embodies both the colonial attraction of Arabesque par excellance simultaneously along with fears of civilization clashes. -

Kazemi Mysteries Alast.Pdf

<NOTE to all: this article has been carefully adjusted with regarded to the type of apostrophe – please do not do a search and replace on apostrophes on this article> <Note to typesetter “@” means a dot under the preceding letter> Mysteries of Alast: The Realm of Subtle Entities (‘Ālam-i dharr) and the Primordial Covenant in the Babi-Baha’i Writings Farshid Kazemi Abstract One of the more esoteric terms in Shi‘i-Shaykhi thought that has found its way into the vast corpus of the Babi-Baha’i sacred scriptures is called ‘the realm of subtle entities’ or ‘ālam-i dharr (lit. world of particles). The source of inspiration for this term (dharr) in the early Shi’i cosmology and cosmogony lies in one of the more important and dramatic scenes which informs the whole spectrum of Islamic thought, namely the primordial covenant of Qur’an 7:171-2. It is there, in what seems to be pre-existence, that God addresses humanity in the form of particles or seeds (dharr) saying, ‘Am I not your Lord?’ (alastu bi-rabbikum) while the archetype or potential of all future generations of humanity responds with the loving reply, ‘Yes.’ (balā) In light of the significance of this term for the Covenant in the Babi-Baha’i revelations it is surprising that there has only been but passing references to it in some secondary Baha’i sources. In this paper we will outline the history and background of this term and examine some of the interpretations or hermeneutics accorded to it by select examination of its use in Shi‘ism, Shaykhism, and the Babi-Baha’i religions. -

The Three Nephites, the Bodhisattva, and the Mahdi

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Maxwell Institute Publications 2015 Postponing Heaven: The Three Nephites, the Bodhisattva, and the Mahdi Jad Hatem Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi Part of the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Hatem, Jad, "Postponing Heaven: The Three Nephites, the Bodhisattva, and the Mahdi" (2015). Maxwell Institute Publications. 62. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi/62 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maxwell Institute Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Postponing Heaven The Groundwork series places Mormon scrip- ture in dialogue with contemporary theory. By drawing on a broad range of academic disci- plines—including philosophy, theology, literary theory, political theory, social theory, economics, and anthropology—Groundwork books test both the richness of scripture as grounds for con- temporary thought and the relevance of theory to the task of reading scripture. Series Editors Adam S. Miller Joseph M. Spencer Postponing Heaven The Three Nephites, the Bodhisattva, and the Mahdi Jad Hatem Translated by Jonathon Penny Brigham Young University Provo, Utah © 2015 Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, Brigham Young University. All rights reserved. A Groundwork book. Originally published as Les Trois Néphites, le Bodhisattva et le Mahdî: Ou l’ajournement de la béatitude comme acte messianique, Éditions du Cygne, Paris, France, 2007. Permissions. No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means or process without the formal written consent of the publisher. -

Isl241 Course Title: Prophethood and Prophets

NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCE COURSE CODE: ISL241 COURSE TITLE: PROPHETHOOD AND PROPHETS IN ISLAM ISL241 COURSE GUIDE COURSE GUIDE ISL241 PROPHETHOOD AND PROPHETS IN ISLAM Course Team Dr Ismail, L.B. (Developer/Writer) - FCOE (Special) Oyo Biodun Ibrahim (Editor) - NOUN Prof. A.F. Ahmed (Programme Leader) - NOUN Dr Mustapha, A.R. (Coordinator) - NOUN NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA ii ISL241 COURSE GUIDE National Open University of Nigeria Headquarters 14/16 Ahmadu Bello Way Victoria Island Lagos Abuja Office 5, Dar es Salaam Street Off Aminu Kano Crescent Wuse II, Abuja Nigeria e-mail: [email protected] URL: www.noun.edu.ng Published By: National Open University of Nigeria First Printed 2012 ISBN: 978-058-287-8 All Rights Reserved iii ISL241 COURSE GUIDE CONTENTS PAGE Introduction………………………………………………................. 1 What You Will Learn in This Course……………………................. 1 Course Aims……………………………….............………….…….. 1 Course Objectives………………………….............………………. 1 Working through This Course……………..............……………….. 2 Course Materials……………………………….............…………... 2 Textbooks and References……………………...............…………... 3 Assignment File…………………………….............………………. 3 Presentation Schedule……………………...............……………….. 3 Assessment…………………………………..............……………… 3 Tutor-Marked Assignment…………………..............……………… 4 Final Examination Grading…………………….............…..……….. 4 Course Marking Scheme………………………..............….……….. 5 Course Overview………………………………..............………….. -

Culture Maintenance and Identity Among Members of the Druze Community in South Australia

Culture Maintenance and Identity among Members of the Druze Community in South Australia by Denice Daou MIntStud School of International Studies University of South Australia [email protected] (08) 8302 0672 and Giancarlo Chiro Ph D School of International Studies University of South Australia [email protected] (08) 8302 4653 September 2008 2 Cultural Maintenance and Identity among Members of the Druze Community in South Australia Abstract The paper investigates the cultural values and identity of Druze community members in South Australia. The conceptual framework and approach to the study is provided by Humanistic Sociology, according to which cultural and social phenomena can only be fully understood if they are studied from the point of view of the participants (Smolicz, 1999: 283–308). The data for the present research were gathered in several intensive interview sessions with a small group of participants of Druze origin combined with the participant observations of one of the authors who is also of Druze origin. The study demonstrates the successful establishment of the Druze community in South Australia and their general maintenance of Druze cultural values and identities. In addition to the impact of modernisation on traditional values and practices, such as marriage and family values, the research identifies changes in cultural and political values of the Druze community in South Australia as a result of the impact of more recent arrivals. Key words Culture maintenance cultural identity cultural values Druze religion 3 Total word count: 3045Introduction The Druze who have maintained a presence in South Australia since the late 19th century represent a relatively small cultural group which currently includes some 450 familiesi. -

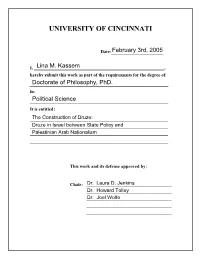

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ The Construction of Druze Ethnicity: Druze in Israel between State Policy and Palestinian Arab Nationalism A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Political Science of the College of Arts and Sciences 2005 by Lina M. Kassem B.A. University of Cincinnati, 1991 M.A. University of Cincinnati, 1998 Committee Chair: Professor Laura Jenkins i ABSTRACT: Eric Hobsbawm argues that recently created nations in the Middle East, such as Israel or Jordan, must be novel. In most instances, these new nations and nationalism that goes along with them have been constructed through what Hobsbawm refers to as “invented traditions.” This thesis will build on Hobsbawm’s concept of “invented traditions,” as well as add one additional but essential national building tool especially in the Middle East, which is the military tradition. These traditions are used by the state of Israel to create a sense of shared identity. These “invented traditions” not only worked to cement together an Israeli Jewish sense of identity, they were also utilized to create a sub national identity for the Druze. The state of Israel, with the cooperation of the Druze elites, has attempted, with some success, to construct through its policies an ethnic identity for the Druze separate from their Arab identity. -

What Is a Call to the Ministry?1 Robert Lewis Dabney

What is a Call to the Ministry?1 Robert Lewis Dabney The church has always held that none should preach the gospel but those who are called of God. The solid proof of this is not to be sought in those places of the Scripture where a special divine call was given to Old Testament prophets and priests, or to apostles, although such passages have been often thus misapplied. Among those misquoted texts should be reckoned Heb. v. 4, which the apostle there applies, not to ministers, but to priests, and especially Christ. The call of these peculiar classes was extraordinary and by special revelation, suited to those days of theophanies and inspiration. But those days have now ceased, and God governs his church exclusively by his providence, and the Holy Spirit applying the written Scriptures. Yet there is a general analogy between the call of a prophet or apostle and that of a gospel preacher, in that both are, in some form, from God, and both summon men to a ministry for God. The true proof that none now should preach but those called of God is rather to be found in such texts as Acts xx. 28, “Take heed . to all the flock over the which the Holy Ghost hath made you overseers “; 1 Cor. xii. 28, etc.; and in the obvious reason that the minister is God’s ambassador, and the sovereign alone can appoint such an agent. What, then, is the call to the gospel ministry? Before the answer to this question is attempted, let us protest against the vague, mystical and fanatical notions of a call which prevail in many minds, fostered, we are sorry to admit, by not a little un-scriptural teaching from Christians.