''Snow Scenes'': Exploring the Role of Memory and Place In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Field Courses of the Royal Meteorological Society

OCCASIONAL PAPERS ON METEOROLOGICAL HISTORY No.17 THE FIELD COURSES OF THE ROYAL METEOROLOGICAL SOCIETY MALCOLM WALKER Published by The Royal Meteorological Society’s History of Meteorology and Physical Oceanography Special Interest Group OCTOBER 2015 ISBN: 978-0-948090-41-7 ROYAL METEOROLOGICAL SOCIETY 104 OXFORD ROAD – READING – RG1 7LL – UNITED KINGDOM Telephone: +44 (0)118 956 8500 Fax: +44 (0)118 956 8571 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.rmets.org Registered charity number 208222 © Royal Meteorological Society 2015 i THE FIELD COURSES OF THE ROYAL METEOROLOGICAL SOCIETY Malcolm Walker Royal Meteorological Society October 2015 View across Malham Tarn at about 8pm on 28 July 1959, showing a large cumulus which shortly afterwards showed a marked anvil formation. Photograph by Nancy J Gordon published in Weather, February 1961, 16, 2, p.45. ii iii CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ...................................................................................................... v SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... 1 PART 1 – The formative years POST-WAR ANTECEDENTS ............................................................................................................ 2 THE PIONEER FIELD COURSE ......................................................................................................... 3 TWO COURSES IN 1951 ................................................................................................................ -

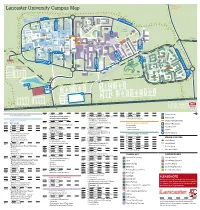

Campus Map CAMPUS

Forrest Hills SOUTH EAST Lancaster University Campus Map CAMPUS NORTH CAMPUS FURNESS AVE B TOWER AVE E C PHYSICS AVE ISO JOHN CREED AVE COUNTY AVE Bailrigg Service Station LANCASTER SQUARE AVE CTP Maintenance GEORGE FOX AVE UNDERPASS Workshops COM PHS WWB County College FYLDE AVE SOUTH CHE CAMPUS D ISS COS The PSC Orchard FAR Bonington Square Step Lancaster TRH Square FAS SBH GFX INF Physics Garden Cycle Route to NORTH DRIVE Fylde College Ellel & Galgate Great Edward SOUTH DRIVE Hall BLN BLM Roberts Court GHC Court Bowland Bowland FUR Wetland North Quad Fylde Grizedale College Quad WEL Furness College Quad Furness Alexandra College Court FYL SAT LIC Square Pendle College Welcome LEC Great Hall Centre CHC Square Reception Engineering F Square Cycle Route to PENDLE AVE ASH Bowland College City Centre BLA Students’ Union ROSSENDALE AVE LIB ENG LSE BLH A Arrival UNH Point University GRIZEDALE AVE House MAN Reception BOWLAND AVE G Graduate College HRB UNDERPASS CPC BOWLAND AVE FARRER AVE GILLOW AVE F Graduate BRH LIBRARY AVE SEC Square A GRADUATE AVE LCC CARTMEL AVE Netball Courts South West I Campus ALEXANDRA PARK DRIVE Barker NORTH WEST RUS House BHF Entrance Lancaster Court House Hotel CAMPUS H Cartmel College Rugby League Pitch PARK BOULEVARD Lacrosse Pitch ECO BARKER HOUSE AVE MED J PRE Lonsdale SOUTH WEST CAMPUS Quad LONSDALE AVE HAZELRIGG LANE Lonsdale College BFB Lake Carter Grass Playing Pitch Astro Turf Pitch L Grass Playing Pitch L Grass Playing Pitch Grass Playing Pitch Grass Playing Pitch 3rd Generation Artificial Pitch Astro Turf -

Knowing Weather in Place: the Helm Wind of Cross Fell

Veale, L., Endfield, G., and Naylor, S. (2014) Knowing weather in place: the Helm Wind of Cross Fell. Journal of Historical Geography, 45 . pp. 25-37. ISSN 0305-7488 Copyright © 2014 The Authors http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/99540 Deposited on: 19 November 2014 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Journal of Historical Geography 45 (2014) 25e37 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Historical Geography journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhg Knowing weather in place: the Helm Wind of Cross Fell Lucy Veale a,*, Georgina Endfield a and Simon Naylor b a University of Nottingham, School of Geography, University Park, Nottingham NG7 2RD, UK b University of Glasgow, School of Geographical and Earth Sciences, East Quadrangle, University Avenue, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK Abstract The Helm Wind of Cross Fell, North Pennines, is England’s only named wind. As a product of the particular landscape found at Cross Fell, the Helm is a true local wind, and a phenomenon that has come to assume great cultural as well as environmental significance in the region and beyond. In this paper we draw on material from county histories, newspaper archives, and documents relating to investigations of the Helm Wind that were conducted by the Royal Meteorological Society between 1884 and 1889, and by British climatologist Gordon Manley (1908e1980), between 1937 and 1939, to document attempts to observe, measure, understand and explain this local wind over a period of 200 years. We show how different ways of knowing the Helm relate to contemporary practices of meteorology, highlighting the shifts that took place in terms of what constituted credible meteorological observation. -

The Helm Wind of Cross Fell

Journal of Historical Geography 45 (2014) 25e37 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Historical Geography journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhg Knowing weather in place: the Helm Wind of Cross Fell Lucy Veale a,*, Georgina Endfield a and Simon Naylor b a University of Nottingham, School of Geography, University Park, Nottingham NG7 2RD, UK b University of Glasgow, School of Geographical and Earth Sciences, East Quadrangle, University Avenue, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK Abstract The Helm Wind of Cross Fell, North Pennines, is England’s only named wind. As a product of the particular landscape found at Cross Fell, the Helm is a true local wind, and a phenomenon that has come to assume great cultural as well as environmental significance in the region and beyond. In this paper we draw on material from county histories, newspaper archives, and documents relating to investigations of the Helm Wind that were conducted by the Royal Meteorological Society between 1884 and 1889, and by British climatologist Gordon Manley (1908e1980), between 1937 and 1939, to document attempts to observe, measure, understand and explain this local wind over a period of 200 years. We show how different ways of knowing the Helm relate to contemporary practices of meteorology, highlighting the shifts that took place in terms of what constituted credible meteorological observation. We also acknowledge the overlapping nature of these ways of knowing and the persistence of multiple testimonies about the Helm and its effects. Ó 2014 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/). -

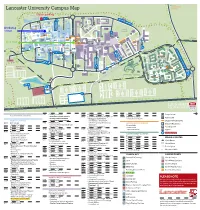

Lancaster University Campus Map CAMPUS

Forrest Hills SOUTH EAST Lancaster University Campus Map CAMPUS NORTH CAMPUSVisitor parking FURNESS AVE B TOWER AVE E C PHYSICS AVE ISO JOHN CREED AVE COUNTY AVE Bailrigg Service Station LANCASTER SQUARE AVE CTP GEORGE FOX AVE Maintenance UNDERPASS Workshops COM PHS WWB Workshop FYLDE AVE County College SOUTH CHE CAMPUS venue D ISS COS The PSC Orchard FAR Bonington Square Step Lancaster TRH Square FAS SBH GFX INF Physics Garden Cycle Route to NORTH DRIVE Fylde College Ellel & Galgate Great Edward SOUTH DRIVE Hall BLN BLM Roberts Court GHC Court Bowland Bowland FUR Wetland North Quad Fylde Grizedale College Bus stop Quad WEL Furness College Quad Furness Alexandra College Court FYL SAT LIC Square LEC Pendle College Great Hall Welcome CHC Square Centre Reception Engineering F Square Cycle Route to PENDLE AVE ASH Bowland College City Centre BLA Students’ Union ROSSENDALE AVE LIB ENG LSE BLH A Arrival UNH Point GRIZEDALE AVE University House MAN Reception BOWLAND AVE G Graduate College HRB UNDERPASS CPC BOWLAND AVE FARRER AVE GILLOW AVE Graduate BRH LIBRARY AVE SEC Square A GRADUATE AVE LCC CARTMEL AVE Netball Courts South West I Campus ALEXANDRA PARK DRIVE Barker NORTH WEST RUS House BHF Entrance Lancaster Court House Hotel CAMPUS H Cartmel College Rugby League Pitch PARK BOULEVARD Lacrosse Pitch ECO BARKER HOUSE AVE MED J PRE Lonsdale SOUTH WEST CAMPUS Quad LONSDALE AVE HAZELRIGG LANE Lonsdale College BFB Lake Carter Grass Playing Pitch Astro Turf Pitch L Grass Playing Pitch L Grass Playing Pitch Grass Playing Pitch Grass Playing Pitch 3rd -

Climatology in the Department of Geography

Climatology in the Department of Geography The Durham Department of Geography's long association with climatology began with Gordon Manley, first Head of Department from 1928 to 1939. Manley was appointed at the early age of 26 and was required to organise and conduct the teaching of geography in the Faculties of Arts and Science and to co-operate with Professor Arthur Holmes in the Department of Geology (Tooley 1985). During his time in Durham, he published papers, among others, on the climate of the northern Pennines, including the helm wind (Sheaill, Kenworthy and Tooley 1985). Later, he was widely known for his articles on weather in the former Manchester Guardian from 1952, copies of which are available in the Durham University library at Palace Green, and his outstanding legacy: Climate and the British Scene (1952) in the New Naturalist Series. He has been described as 'the best known, most prolific and most expert on the climate of Britain of his generation' (Kenworthy 2014). In 1931, Manley became Curator of the University Observatory. He recognised the importance of the continuous meteorological record, being the second longest for a university observatory in Britain after Oxford. He wrote that: ... in this country the published tables of the Oxford record from 1815 have proved to be especially welcome. During my sojourn as Lecturer-in-Charge of the School of Geography in Durham I resolved (my italics) to try to place the records from the University Observatory, of which I am curator, on a similar basis. In the light of other recent work, the temperature record has been considered first. -

Doctors and Patients in Seventeenth-Century

A DYNAMIC EQUILIBRIUM: DOCTORS AND PATIENTS IN SEVENTEENTH- CENTURY ENGLAND by ELIZABETH CONNOLLY BA (Hons) History (First Class), University of Adelaide. A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of History, Faculty of Arts, University of Adelaide. February 2017 Declaration I certify that this work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. In addition, I certify that no part of this work will, in the future, be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university without the prior approval of the University of Adelaide. I give consent to this copy of my thesis when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University’s digital research repository, the Library Search and also through web search engines. I acknowledge the support I have received for my research through the provision of an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. Signed _________________________________ Date ___________________________________ i Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my thesis supervisor Dr. Claire Walker who has been my friend and mentor throughout my candidature. -

Troublesome Wind a Self Guided Walk in the North Pennines

Troublesome wind A self guided walk in the North Pennines Explore the spectacular scenery around Great Dun Fell Discover why it experiences some of the most extreme weather in England Hear remarkable accounts of Britain’s only named wind Find out about one man’s lifetime spent observing the weather .discoveringbritain www .org ies of our land the stor scapes throug discovered h walks 2 Contents Introduction 4 Route overview 5 Practical information 6 Detailed route maps 7 Commentary 9 Credits 30 © The Royal Geographical Society with the Institute of British Geographers, London, 2013 Discovering Britain is a project of the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) The digital and print maps used for Discovering Britain are licensed to the RGS-IBG from Ordnance Survey Cover image: The road down from Great Dun Fell © Lucy Veale 3 Troublesome wind Discover the unique weather of the North Pennines This walk in Cumbria follows the Pennine Way to the summit of Great Dun Fell, the second highest hill in the Pennines. The spectacular scenery of this area also experiences some of the most extreme weather in England. This landscape is the home of Britain’s only named wind, with a remarkable reputation for blowing over horses. This walk explore’s one View towards Knock Pike and the Lake District man’s determination to observe and © Jenny Lunn measure it. It tells the story of Gordon Manley, the geographer who pioneered the collection of meteorological data. Visit the site of one of his weather stations on the summit of Great Dun Fell. Discover what he measured and why he kept returning to this unique landscape. -

Irculation August 2013

No. 118 irculation August 2013 Chilean hydrologyChilean hydrology CIRCULATION – THE NEWSLETTER OF THE BRITISH HYDROLOGICAL SOCIETY 1 Contents Chilean hydrology Chilean hydrology JAMES BATHURST (NEWCASTLE UNIVERSITY) The role of the hydrologist has been on sabbatical at the Universidad Austral de Chile at Valdivia during April-August 2013, as Environmental Clerk of researching the impact of forest plantation on Works soil erosion. Here he presents a personal view of Chilean hydrology and water resources. AGM Improbably thin, Chile stretches from within the tropics Peter Wolf Early Career to Cape Horn at a latitude equivalent to Edinburgh, Event providing just about every hydro-logical environment except tropical rain forest. North to south, it can be Urban aquatic ecosystems split into the Atacama desert (so dry that NASA uses it as a Mars analogue),a central region grading from EGU General Assembly Mediterranean climate (Santiago annual rainfall 360 mm) Impact of changes in the to temperate rain forest (Valdivia 2500 mm) and a cold and even more rainy southern region (over 3000 mm hydrological cycle in Patagonia). Water so defines the southern end of the Data-based mechanistic Central Valley that two of Chile’s administrative regions are named The Lakes and The Rivers. West-east there are methods for hydrological significant variations from the Coastal Cordillera, across modelling, forecasting and the Central Valley and into the Andes, where snowmelt emulation and glaciers form important water sources. Volcanoes and earthquakes add their own hydrological impacts. Knowledge for the future Hydrology at Lancaster Obit: Elizabeth M Shaw UK Hydrological Bulletin Letter to the Editor COVER PICTURE shows the outlet flume and gauging hut at the La Reina experimental catchment south of Valdivia. -

Weather and Climate Is Available As a Download

Chapter 2 Weather and Climate Ken Cook and Ian Findlay Weardale weather © Ian Turner Introduction The Pennines are unique in England as the only significant upland area not close to the sea, with climatic implications. The high hills (up to 740 m AOD at the source of the Wear) maintain wet and cool conditions in the upper Dale and cast a rain shadow, creating drier conditions to the east. Yet gales from the north and east can bring heavy rain, and snow in the winter. Neighbouring Teesdale is unique in having more data and long-term weather stations than any other UK upland area. A continuous temperature record is available from 1931 (Holden & Adamson, 2001). Gordon Manley of Durham University began recording at Moor House at 550 m in the 1950s. Some parallels may be drawn from these records for Weardale, where local records go back to 1970. 41 What are conditions like? Gordon Manley summarised the climate at high altitudes in the Pennines as follows; ‘We therefore form a conception of excessively windy and pervasively wet autumn, a very variable and stormy winter with long spells of snow cover, high humidity and extremely bitter wind, alternating with brief periods of rain and thaw. April has a mean temperature little above the freezing point and sunny days in May are offset by cold polar air, while the short and cloudy summer is not quite warm enough for the growth of trees. Throughout the year, indeed, the summers are frequently covered in cloud’. The climate above 750 m is tundra/sub-polar oceanic. -

PDF Version of SPRI Review 2013

Scott Polar Research Institute Review 2013 87th Annual Report of the Scott Polar Research Institute University of Cambridge, UK 1 Memorial to Sir John Franklin, Waterloo Place, London Contents Director’s Introduction 2 Institute Staff 4 Polar Research 6 Research Group Structure Polar Physical Science Polar Social Science and Humanities Current Research Grants Publications by Institute Staff 14 Books Papers in Peer-Reviewed Journals Chapters in Books and Other Contributions Doctoral and Masters Theses Seminars Polar Information and Historic Archives 17 Library and Information Service World Data Centre for Glaciology, Cambridge Picture Library Archives Polar Record SPRI Website Teaching, Learning and Understanding 20 University Teaching The Polar Museum Education and Outreach Projecting the Significance of the Polar Regions Expedition Support: Gino Watkins Funds External Contributions to Polar Activities 23 National and International Roles of Staff International Glaciological Society (IGS) Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) Fundraising and the SPRI Appeal 24 Friends of the Scott Polar Research Institute SPRI Appeal Director’s Introduction A very important part of the Institute’s activity is through the research of our post-doctoral staff and students, who together number between 30 and 40 in most years, working under the supervision of our senior academics. Many research students and post-doctoral staff of the Institute, in both the polar sciences and social sciences, have gone on to academic posts in universities in the UK and overseas. This provides clear external recognition of the high quality of their research work and of the strong research culture within the Institute. This year, for example, Dr Steven Palmer and Dr Kelly Hogan have obtained established posts in Exeter University and the British Antarctic Survey, respectively, and Dr Alison Banwell was awarded a prestigious Junior Research Fellowship at St. -

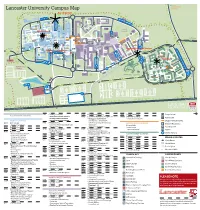

Lancaster University Campus Map CAMPUS

Forrest Hills SOUTH EAST Lancaster University Campus Map CAMPUS NORTH CAMPUS FURNESS AVE B TOWER AVE E C AVE PHYSICS ISO JOHN CREED AVE COUNTY AVE Bailrigg Service Station LANCASTER SQUARE AVE CTP Maintenance GEORGE FOX AVE UNDERPASS Workshops COM PHS WWB County College FYLDE AVE SOUTH CHE CAMPUS D ISS COS The PSC Orchard FAR Bonington Square Step Lancaster TRH Square FAS SBH GFX INF Physics Garden Cycle Route to NORTH DRIVE Fylde College Ellel & Galgate Great Edward SOUTH DRIVE Hall BLN BLM Roberts Court GHC Court Bowland Bowland FUR Wetland North Quad Fylde Grizedale College Quad WEL Furness College Quad Furness Alexandra College Court FYL SAT Square LIC Pendle College Welcome LEC Great Hall Centre CHC Square Reception Engineering F Square Cycle Route to PENDLE AVE ASH Bowland College City Centre BLA Students’ Union ROSSENDALE AVE AVE ROSSENDALE LIB ENG LSE BLH A Arrival UNH Point GRIZEDALE AVE University House MAN Reception BOWLAND AVE BOWLAND G Graduate College HRB UNDERPASS CPC BOWLAND AVE FARRER AVE GILLOW AVE GILLOW F Graduate BRH AVE LIBRARY SEC Square A GRADUATE AVE LCC CARTMEL AVE Netball Courts South West I Campus ALEXANDRA PARK DRIVE Barker NORTH WEST RUS House BHF Entrance Lancaster Court House Hotel CAMPUS H Cartmel College Rugby League Pitch PARK BOULEVARD Lacrosse Pitch ECO BARKER HOUSE AVE MED J PRE Lonsdale SOUTH WEST CAMPUS Quad LONSDALE AVE HAZELRIGG LANE Lonsdale College BFB Lake Carter Grass Playing Pitch Astro Turf Pitch L Grass Playing Pitch L Grass Playing Pitch Grass Playing Pitch Grass Playing Pitch 3rd Generation