Doctors and Patients in Seventeenth-Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Births, Marriages, and Deaths

DEC. 31, 1955 MEDICAL NEWS MEDICALBRrsIJOURNAL. 1631 Lead Glazes.-For some years now the pottery industry British Journal of Ophthalmology.-The new issue (Vol. 19, has been forbidden to use any but leadless or "low- No. 12) is now available. The contents include: solubility" glazes, because of the risk of lead poisoning. EXPERIENCE IN CLINIcAL EXAMINATION OP CORNEAL SENsITiVrry. CORNEAL SENSITIVITY AND THE NASO-LACRIMAL REFLEX AFTER RETROBULBAR However, in some teaching establishments raw lead glazes or ANAES rHESIA. Jorn Boberg-Ans. glazes containing a high percentage of soluble lead are still UVEITIS. A CLINICAL AND STATISTICAL SURVEY. George Bennett. INVESTIGATION OF THE CARBONIC ANHYDRASE CONTENT OF THE CORNEA OF used. The Ministry of Education has now issued a memo- THE RABBIT. J. Gloster. randum to local education authorities and school governors HYALURONIDASE IN OCULAR TISSUES. I. SENSITIVE BIOLOGICAL ASSAY FOR SMALL CONCENTRATIONS OF HYALURONIDASE. CT. Mayer. (No. 517, dated November 9, 1955) with the object of INCLUSION BODIES IN TRACHOMA. A. J. Dark. restricting the use of raw lead glazes in such schools. The TETRACYCLINE IN TRACHOMA. L. P. Agarwal and S. R. K. Malik. APPL IANCES: SIMPLE PUPILLOMETER. A. Arnaud Reid. memorandum also includes a list of precautions to be ob- LARGE CONCAVE MIRROR FOR INDIRECT OPHTHALMOSCOPY. H. Neame. served when handling potentially dangerous glazes. Issued monthly; annual subscription £4 4s.; single copy Awards for Research on Ageing.-Candidates wishing to 8s. 6d.; obtainable from the Publishing Manager, B.M.A. House, enter for the 1955-6 Ciba Foundation Awards for research Tavistock Square, London, W.C.1. -

The Eagle 1946 (Easter)

THE EAGLE ut jVfagazine SUPPORTED BY MEMBERS OF Sf 'John's College St. Jol.l. CoIl. Lib, Gamb. VOL UME LIl, Nos. 231-232 PRINTED AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS FOR SUBSCRIBERS ON L Y MCMXLVII Ct., CONTENTS A Song of the Divine Names . PAGE The next number shortly to be published will cover the 305 academic year 1946/47. Contributions for the number The College During the War . 306 following this should be sent to the Editors of The Eagle, To the College (after six war-years in Egypt) 309 c/o The College Office, St John's College. The Commemoration Sermon, 1946 310 On the Possible Biblical Origin of a Well-Known Line in The The Editors will welcome assistance in making the Chronicle as complete a record as possible of the careers of members Hunting of the Snark 313 of the College. The Paling Fence 315 The Sigh 3 1 5 Johniana . 3 16 Book Review 319 College Chronicle : The Adams Society 321 The Debaj:ing Society . 323 The Finar Society 324 The Historical Society 325 The Medical Society . 326 The Musical Society . 329 The N ashe Society . 333 The Natural Science Club 3·34 The 'P' Club 336 Yet Another Society 337 Association Football 338 The Athletic Club 341 The Chess Club . 341 The Cricket Club 342 The Hockey Club 342 L.M.B.C.. 344 Lawn Tennis Club 352 Rugby Football . 354 The Squash Club 358 College Notes . 358 Obituary: Humphry Davy Rolleston 380 Lewis Erle Shore 383 J ames William Craik 388 Kenneth 0 Thomas Wilson 39 J ames 391 John Ambrose Fleming 402 Roll of Honour 405 The Library . -

POLITICS, SOCIETY and CIVIL WAR in WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History

Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History Series editors ANTHONY FLETCHER Professor of History, University of Durham JOHN GUY Reader in British History, University of Bristol and JOHN MORRILL Lecturer in History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow and Tutor of Selwyn College This is a new series of monographs and studies covering many aspects of the history of the British Isles between the late fifteenth century and the early eighteenth century. It will include the work of established scholars and pioneering work by a new generation of scholars. It will include both reviews and revisions of major topics and books which open up new historical terrain or which reveal startling new perspectives on familiar subjects. It is envisaged that all the volumes will set detailed research into broader perspectives and the books are intended for the use of students as well as of their teachers. Titles in the series The Common Peace: Participation and the Criminal Law in Seventeenth-Century England CYNTHIA B. HERRUP Politics, Society and Civil War in Warwickshire, 1620—1660 ANN HUGHES London Crowds in the Reign of Charles II: Propaganda and Politics from the Restoration to the Exclusion Crisis TIM HARRIS Criticism and Compliment: The Politics of Literature in the Reign of Charles I KEVIN SHARPE Central Government and the Localities: Hampshire 1649-1689 ANDREW COLEBY POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, i620-1660 ANN HUGHES Lecturer in History, University of Manchester The right of the University of Cambridge to print and sell all manner of books was granted by Henry VIII in 1534. -

The Field Courses of the Royal Meteorological Society

OCCASIONAL PAPERS ON METEOROLOGICAL HISTORY No.17 THE FIELD COURSES OF THE ROYAL METEOROLOGICAL SOCIETY MALCOLM WALKER Published by The Royal Meteorological Society’s History of Meteorology and Physical Oceanography Special Interest Group OCTOBER 2015 ISBN: 978-0-948090-41-7 ROYAL METEOROLOGICAL SOCIETY 104 OXFORD ROAD – READING – RG1 7LL – UNITED KINGDOM Telephone: +44 (0)118 956 8500 Fax: +44 (0)118 956 8571 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.rmets.org Registered charity number 208222 © Royal Meteorological Society 2015 i THE FIELD COURSES OF THE ROYAL METEOROLOGICAL SOCIETY Malcolm Walker Royal Meteorological Society October 2015 View across Malham Tarn at about 8pm on 28 July 1959, showing a large cumulus which shortly afterwards showed a marked anvil formation. Photograph by Nancy J Gordon published in Weather, February 1961, 16, 2, p.45. ii iii CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ...................................................................................................... v SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... 1 PART 1 – The formative years POST-WAR ANTECEDENTS ............................................................................................................ 2 THE PIONEER FIELD COURSE ......................................................................................................... 3 TWO COURSES IN 1951 ................................................................................................................ -

Acknowledgements There Are Several People Without

Acknowledgements There are several people without whose assistance this thesis could not have been produced. I would like to thank, in particular, the following: Dr Alan Marshal, my supervisor at Bath Spa University College, for his constant nagging to 'get on with it'; Professor Roger Richardson of King Alfred's for his support as my external supervisor; Bath Spa University College for a constant supply of Inter Library Loans, a bursary and a travel grant to Spain; The Andrew C. Duncan Catholic History Trust for a research grant; Mgr Peter Pooling and the staff at Collegio Ingleses, Valladolid, Spain for their hospitality and access to their Archives; Mgr Michael Williams, for his assistance at Archive General, Simancas; Fr Daniel Rees, Librarian, Downside Abbey, Stratton on the Fosse, Somerset for access to the monastic library; Dr Dominic Bellenger and Dr Elaine Chalus, for their support and suggestions; Dr Ratal Witkowski, for Polish biographies; Joan Pattison, Dick Meyer, Irene Stansby for French, Dutch and Polish translations respectively; and David and Louise for being there. I would also like to thank Dr Paul Hyland & Doctor Barry Coward for their useful comments and suggestions that have enabled me to complete this work successfully. This thesis is dedicated to the memory of Charlotte May Anderson (May, 1977). Phis copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Contents List of Illustrations Abbreviations Preface 12 Introduction 22 1. James VI and I and the Early Seventeenth-Century Political Scene 27 2. -

Henry More, Richard Baxter, and Francis Glisson's Trea Tise on the Energetic Na Ture of Substance

Medical History, 1987, 31: 15-40. MEDICINE AND PNEUMATOLOGY: HENRY MORE, RICHARD BAXTER, AND FRANCIS GLISSON'S TREA TISE ON THE ENERGETIC NA TURE OF SUBSTANCE by JOHN HENRY* The nature of the soul and its relationship to the body has always proved problematical for Christian philosophy. The source ofthe difficulty can be traced back to the efforts of the early Fathers to reconcile the essentially pagan concept of an immaterial and immortal soul with apostolic teachings about the after-life in which all the emphasis is placed upon the resurrection of the body. The tensions between these two traditions inevitably became strained during the sixteenth century when Protestant reformers insisted on a closer adherence to Scripture. Furthermore, even when leaving the problems of Scriptural hermeneutics aside, the dualistic approach to the question, in which soul (or spirit) and body are held to be categorically different in essence, had to overcome a number of intractable philosophical problems. So, it was not simply coincidence that when the new mechanical philosophy began to be formulated in a systematic way in the seventeenth century, it was couched in vigorously dualistic terms. In fact, three of the earliest fully elaborated systems of mechanical philosophy, those of Descartes, Digby, and Charleton, were explicitly intended to provide a philosophical prop for dualist theology.' Moreover, it was because of its usefulness in promoting dualism that Cartesianism was first popularized in England not by a natural philosopher but by the Cambridge Platonist and theologian, Henry More.2 *John Henry, MPhil, PhD, Wellcome Institute for the History ofMedicine, 183 Euston Road, London NWI 2BP. -

Slater V. Baker and Stapleton (C.B. 1767): Unpublished Monographs by Robert D. Miller

SLATER V. BAKER AND STAPLETON (C.B. 1767): UNPUBLISHED MONOGRAPHS BY ROBERT D. MILLER ROBERT D. MILLER, J.D., M.S. HYG. HONORARY FELLOW MEDICAL HISTORY AND BIOETHICS DEPARTMENT SCHOOL OF MEDICINE AND PUBLIC HEALTH UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN - MADISON PRINTED BY AUTHOR MADISON, WISCONSIN 2019 © ROBERT DESLE MILLER 2019 BOUND BY GRIMM BOOK BINDERY, MONONA, WI AUTHOR’S INTRODUCTION These unpublished monographs are being deposited in several libraries. They have their roots in my experience as a law student. I have been interested in the case of Slater v. Baker and Stapleton since I first learned of it in law school. I was privileged to be a member of the Yale School Class of 1974. I took an elective course with Dr. Jay Katz on the protection of human subjects and then served as a research assistant to Dr. Katz in the summers of 1973 and 1974. Dr. Katz’s course used his new book EXPERIMENTATION WITH HUMAN BEINGS (New York: Russell Sage Foundation 1972). On pages 526-527, there are excerpts from Slater v. Baker. I sought out and read Slater v. Baker. It seemed that there must be an interesting backstory to the case, but it was not accessible at that time. I then practiced health law for nearly forty years, representing hospitals and doctors, and writing six editions of a textbook on hospital law. I applied my interest in experimentation with human beings by serving on various Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) during that period. IRBs are federally required committees that review and approve experiments with humans at hospitals, universities and other institutions. -

260 Paul Kléber Monod This Is an Ambitious Book. Monod's

260 book reviews Paul Kléber Monod Solomon’s Secret Arts: The Occult in the Age of Enlightenment, New Haven and London: Yale University Press 2013. x + 430 pp. isbn 978-0-300-12358-6. This is an ambitious book. Monod’s subject is the occult, by which he means ‘a type of thinking expressed either in writing or in action, that allowed the boundary between the natural and the supernatural to be crossed by the ac- tions of human beings’ (p. 5). Although he cites the work of Antoine Faivre, Wouter Hanegraaff and others, readers of Aries will doubtless be interested to learn Monod’s reasoning for using the term occult in preference to West- ern esotericism. In short, while acknowledging the important contribution of the ‘esoteric approach’ he also highlights its perceived ‘shortcomings’, namely a tendency to regard relevant texts as ‘comprising a discrete and largely self- referential intellectual tradition, hermetically sealed so as to ward off the taint of other forms of thought, not to mention social trends and popular practices’. Moreover, ‘scholars of esoteric religion’ apparently ‘have a tendency to inter- pret whatever they are studying with the greatest seriousness, so that hucksters and charlatans turn into philosophers, and minor references in obscure eso- teric works take on labyrinthine significances’ (p. 10). In practice, what Monod understands here as the occult is largely restricted to alchemy, astrology and rit- ual magic; a maelstrom which, among other things, pulled in readers of Hermes Trismegistus, Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, Paracelsus, Jacob Boehme and the Kabbalah, outwardly respectable scientists and anti-Trinitarians (sometimes one and the same); Philadelphians; French Prophets; Freemasons; students of Ancient Britain and the Druids; cunning folk; authors of popular Gothic novels; certain followers of Emmanuel Swedenborg; Neoplatonists; advocates of Ani- mal magnetism; and Judaized millenarians. -

A Brief Overview of Urology's Development

A brief overview of urology’s development Milestones in urology show evolutionary growth Prof. Manuel Mendes upper urinary tract diseases, namely kidney disease, Modern advances Silva with Albarran’s invention of a moveable “lever” for Advances continue to be made, not only in Former president adjusting the cystoscope, making it possible to insert fundamental aspects of the basic sciences, but also in Portuguese tubes (catheters) up into the ureters and kidneys. This new and sophisticated methods of diagnosis and Association of Urology made it possible to analyse the urine produced by treatment. These include computerised imaging Lisbon (PT) each kidney separately, thereby facilitating lateral techniques: ultrasound, computed axial tomography diagnosis. The most common diseases of the time, of (CAT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), digital and which tuberculosis was the most prevalent, were very Doppler angiography, radioactive isotopes; analytical, mmendessilva@ different from those we see today. immunological, genetic and pathology-based sapo.pt methods of diagnosis; sophisticated tools for studying urodynamics; new methods of endoscopic and laser “...it was only toward the end of the diagnosis and treatment, such as endourology Urinary and genital diseases have been around since century, after electricity came into (ureterorenoscopy, percutaneous surgery), internal time immemorial. We know this from the evidence and external shockwave lithotripsy, laparoscopy and left behind –urinary stones discovered in Egyptian use, that Max Nitze (1877) achieved laparoscopic surgery, and robotic surgery and mummies and alongside numerous skeletal remains- a good quality cystoscopy using a telesurgery; control of infection with vaccines and and in vestiges of ancient civilisations such as new generation antibiotics; new techniques for paintings and writing tablets. -

Who Is Thomas Linacre? James F

The Linacre Quarterly Volume 22 | Number 3 Article 2 8-1-1955 Who is Thomas Linacre? James F. Gilroy Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/lnq Part of the Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, and the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Gilroy, James F. (1955) "Who is Thomas Linacre?," The Linacre Quarterly: Vol. 22 : No. 3 , Article 2. Available at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/lnq/vol22/iss3/2 Linacre's collation of manuscripts and for seven miles around, and in the Vatican libraries gained him for the punishment of offenders. a reputation as an authority in Four years afterwards these privi Who is Thomas Linacre? Humanistic learning. During the leges and responsibilities were course of these studies he became confirmed by statute and extended JAMES F. GILROY, S.J. so interested in the ancient writers to the whole country. "3 Linacre on medicine that he directed his financed the whole project out of EW PHYSICIANS have ever done reform and too conscientious not studies to this field and earned a his own fortune, since the royal more for their profession F than to do his best to bring it about. To doctor of medicine degree at the charter made no provision for sup Thomas Linacre. When he re combat the ignorance of scientific University of Padua. port. ceived his M.D. at the beginning medical methods he gave lectures of the fifteenthcentury, the practice After his return from Italy Lin The importance of this establish at Oxford and established reader ment can be seen, for "no profes of medicine in England was car acre was chosen tutor and physi ships in medicine at Oxford and sional foundation, at home or ried on largely by "a great multi cian to Prince Arthur and teacher Cambridge. -

Campus Map CAMPUS

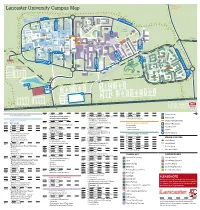

Forrest Hills SOUTH EAST Lancaster University Campus Map CAMPUS NORTH CAMPUS FURNESS AVE B TOWER AVE E C PHYSICS AVE ISO JOHN CREED AVE COUNTY AVE Bailrigg Service Station LANCASTER SQUARE AVE CTP Maintenance GEORGE FOX AVE UNDERPASS Workshops COM PHS WWB County College FYLDE AVE SOUTH CHE CAMPUS D ISS COS The PSC Orchard FAR Bonington Square Step Lancaster TRH Square FAS SBH GFX INF Physics Garden Cycle Route to NORTH DRIVE Fylde College Ellel & Galgate Great Edward SOUTH DRIVE Hall BLN BLM Roberts Court GHC Court Bowland Bowland FUR Wetland North Quad Fylde Grizedale College Quad WEL Furness College Quad Furness Alexandra College Court FYL SAT LIC Square Pendle College Welcome LEC Great Hall Centre CHC Square Reception Engineering F Square Cycle Route to PENDLE AVE ASH Bowland College City Centre BLA Students’ Union ROSSENDALE AVE LIB ENG LSE BLH A Arrival UNH Point University GRIZEDALE AVE House MAN Reception BOWLAND AVE G Graduate College HRB UNDERPASS CPC BOWLAND AVE FARRER AVE GILLOW AVE F Graduate BRH LIBRARY AVE SEC Square A GRADUATE AVE LCC CARTMEL AVE Netball Courts South West I Campus ALEXANDRA PARK DRIVE Barker NORTH WEST RUS House BHF Entrance Lancaster Court House Hotel CAMPUS H Cartmel College Rugby League Pitch PARK BOULEVARD Lacrosse Pitch ECO BARKER HOUSE AVE MED J PRE Lonsdale SOUTH WEST CAMPUS Quad LONSDALE AVE HAZELRIGG LANE Lonsdale College BFB Lake Carter Grass Playing Pitch Astro Turf Pitch L Grass Playing Pitch L Grass Playing Pitch Grass Playing Pitch Grass Playing Pitch 3rd Generation Artificial Pitch Astro Turf -

History of Medicine in the City of London

[From Fabricios ab Aquapendente: Opere chirurgiche. Padova, 1684] ANNALS OF MEDICAL HISTORY Third Series, Volume III January, 1941 Number 1 HISTORY OF MEDICINE IN THE CITY OF LONDON By SIR HUMPHRY ROLLESTON, BT., G.C.V.O., K.C.B. HASLEMERE, ENGLAND HET “City” of London who analysed Bald’s “Leech Book” (ca. (Llyn-din = town on 890), the oldest medical work in Eng the lake) lies on the lish and the textbook of Anglo-Saxon north bank of the leeches; the most bulky of the Anglo- I h a m e s a n d Saxon leechdoms is the “Herbarium” stretches north to of that mysterious personality (pseudo-) Finsbury, and east Apuleius Platonicus, who must not be to west from the confused with Lucius Apuleius of Ma- l ower to Temple Bar. The “city” is daura (ca. a.d. 125), the author of “The now one of the smallest of the twenty- Golden Ass.” Payne deprecated the un nine municipal divisions of the admin due and, relative to the state of opin istrative County of London, and is a ion in other countries, exaggerated County corporate, whereas the other references to the imperfections (super twenty-eight divisions are metropolitan stitions, magic, exorcisms, charms) of boroughs. Measuring 678 acres, it is Anglo-Saxon medicine, as judged by therefore a much restricted part of the present-day standards, and pointed out present greater London, but its medical that the Anglo-Saxons were long in ad history is long and of special interest. vance of other Western nations in the Of Saxon medicine in England there attempt to construct a medical litera is not any evidence before the intro ture in their own language.