View of Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paul Iribe (1883–1935) Was Born in Angoulême, France

4/11/2019 Bloomsbury Fashion Central - BLOOMSBURY~ Sign In: University of North Texas Personal FASHION CENTRAL ~ No Account? Sign Up About Browse Timelines Store Search Databases Advanced search --------The Berg Companion to Fashion eBook Valerie Steele (ed) Berg Fashion Library IRIBE, PAUL Michelle Tolini Finamore Pages: 429–430 Paul Iribe (1883–1935) was born in Angoulême, France. He started his career in illustration and design as a newspaper typographer and magazine illustrator at numerous Parisian journals and daily papers, including Le temps and Le rire. In 1906 Iribe collaborated with a number of avantgarde artists to create the satirical journal Le témoin, and his illustrations in this journal attracted the attention of the fashion designer Paul Poiret. Poiret commissioned Iribe to illustrate his first major dress collection in a 1908 portfolio entitled Les robes de Paul Poiret racontées par Paul Iribe . This limited edition publication (250 copies) was innovative in its use of vivid fauvist colors and the simplified lines and flattened planes of Japanese prints. To create the plates, Iribe utilized a hand coloring process called pochoir, in which bronze or zinc stencils are used to build up layers of color gradually. This publication, and others that followed, anticipated a revival of the fashion plate in a modernist style to reflect a newer, more streamlined fashionable silhouette. In 1911 the couturier Jeanne Paquin also hired Iribe , along with the illustrators Georges Lepape and Georges Barbier, to create a similar portfolio of her designs, entitled L’Eventail et la fourrure chez Paquin. Throughout the 1910s Iribe became further involved in fashion and added design for theater, interiors, and jewelry to his repertoire. -

Givenchy Exudes French Elegance at Expo Classic Luxury Brand Showcasing Latest Stylish Products for Chinese Customers

14 | FRANCE SPECIAL Wednesday, November 6, 2019 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY Givenchy exudes French elegance at expo Classic luxury brand showcasing latest stylish products for Chinese customers This lipstick is a tribute and hom Givenchy has made longstanding age to the first Rouge Couture lip ties with China and a fresh resonance stick created by Hubert James Taffin in the country. The Mini Eden bag (left) de Givenchy, which had a case and Mini Mystic engraved with multiples 4Gs. History of style handbag are Givenchy’s Thirty years after Givenchy Make The history of Givenchy is a centerpieces at the CIIE. up was created, these two shades also remarkable one. have engraved on them the same 4Gs. The House of Givenchy was found In 1952, Hubert James Taffin de ed by Hubert de Givenchy in 1952. Givenchy debuted a collection of “sep The name came to epitomize stylish arates” — elegant blouses and light elegance, and many celebrities of the skirts with architectural lines. Accom age made Hubert de Givenchy their panied by the most prominent designer of choice. designers of the time, he established When Hubert de Givenchy arrived new standards of elegance and in Paris from the small town of Beau launched his signature fragrance, vais at the age of 17, he knew he want L’Interdit. ed to make a career in fashion design. In 1988, Givenchy joined the He studied at the Ecole des Beaux LVMH Group, where the couturier Arts in Versailles and worked as an remained until he retired in 1995. assistant to the influential designer, Hubert de Givenchy passed away Jacques Fath. -

Puvunestekn 2

1/23/19 Costume designers and Illustrations 1920-1940 Howard Greer (16 April 1896 –April 1974, Los Angeles w as a H ollywood fashion designer and a costume designer in the Golden Age of Amer ic an cinema. Costume design drawing for Marcella Daly by Howard Greer Mitc hell Leis en (October 6, 1898 – October 28, 1972) was an American director, art director, and costume designer. Travis Banton (August 18, 1894 – February 2, 1958) was the chief designer at Paramount Pictures. He is considered one of the most important Hollywood costume designers of the 1930s. Travis Banton may be best r emembered for He held a crucial role in the evolution of the Marlene Dietrich image, designing her costumes in a true for ging the s tyle of s uc h H ollyw ood icons creative collaboration with the actress. as Carole Lombard, Marlene Dietrich, and Mae Wes t. Costume design drawing for The Thief of Bagdad by Mitchell Leisen 1 1/23/19 Travis Banton, Travis Banton, Claudette Colbert, Cleopatra, 1934. Walter Plunkett (June 5, 1902 in Oakland, California – March 8, 1982) was a prolific costume designer who worked on more than 150 projects throughout his career in the Hollywood film industry. Plunk ett's bes t-known work is featured in two films, Gone with the Wind and Singin' in the R ain, in which he lampooned his initial style of the Roaring Twenties. In 1951, Plunk ett s hared an Osc ar with Orr y-Kelly and Ir ene for An Amer ic an in Paris . Adr ian Adolph Greenberg ( 1903 —19 59 ), w i de l y known Edith H ead ( October 28, 1897 – October 24, as Adrian, was an American costume designer whose 1981) was an American costume designer mos t famous costumes were for The Wiz ard of Oz and who won eight Academy Awards, starting with other Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films of the 1930s and The Heiress (1949) and ending with The Sting 1940s. -

Final J.Min |O.Phi |T.Cun |Editor |Copy

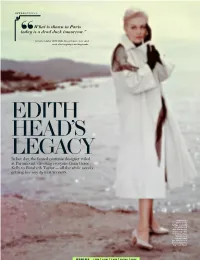

Style SPeCIAl What is shown in Paris today is a dead duck tomorrow.” — Costume designer EDITH HEAD, whose 57-year career owed “ much of its longevity to avoiding trends. C Edith Head’s LEgacy In her day, the famed costume designer ruled at Paramount, dressing everyone from Grace Kelly to Elizabeth Taylor — all the while savvily getting her way By Sam Wasson Kim Novak’s wardrobe for Vertigo, including this white coat with black scarf, was designed to look mysterious. “This girl must look as if she’s just drifted out of the San Francisco fog,” said Head. FINAL J.MIN |O.PHI |T.CUN |EDITOR |COPY Costume designer edith head — whose most unforgettable designs included Grace Kelly’s airy chiffon skirt in Hitchcock’s To Catch a Thief, Gloria Swanson’s darkly elegant dresses in Sunset Boulevard, Dorothy Lamour’s sarongs, and Elizabeth Taylor’s white satin gown in A Place in the Sun — sur- vived 40 years of changing Hollywood styles by skillfully eschewing fads of the moment and, for the most part, gran- Cdeur and ornamentation, too. Boldness, she believed, was a vice. Thirty years after her death, Head is getting a new dose of attention. A gor- geous coffee table book,Edith Head: The Fifty-Year Career of Hollywood’s Greatest Costume Designer, was recently published. And in late March, an A to Z adapta- tion of Head’s seminal 1959 book, The Dress Doctor, is being released as well. ! The sTyle setter of The screen The breezy volume spotlights her trade- Clockwise from above: 1. -

Givenchy's Red Carpet Legacy

Style Tribute Givenchy’s Red Carpet Legacy A historian notes how Hollywood style stems from the designer’s ‘marriage’ to Audrey Hepburn By Bronwyn Cosgrave n March 10, French master of the little O black dress Hubert de Givenchy died at the age of 91. But his partnership with Audrey Hepburn throughout the 1950s and ’60s forged a bond between Hollywood and haute couture that lives on. 1 Hepburn in a 1958 fitting That legacy was front and center this with designer Givenchy at his Paris atelier. 2 The awards season. Long black dresses — evoca- designer and his muse in 1 1983. 3 The 1970 facade of tive of the dark, languorous Givenchy gown the French fashion house, that Hepburn, as Holly Golightly, wears in which was founded in 1952. the opening scene of her best-known film, Breakfast at Tiffany’s — dominated the run-up 3 to the Oscars as the formal garb of Time’s Up. The protest movement’s sartorial ethos also resonates with Hepburn’s decision to exclusively wear Givenchy onscreen and at the Oscars through much of her career. After she GETTY IMAGES. / visited Givenchy’s Paris atelier in 1953 — to secure him as her designer for Sabrina — she considered his designs to be her uniform. “I felt so good in his clothes,” she once said. Before Hepburn and Givenchy worked GETTY IMAGES. HEAD: PARAMOUNT together, Hollywood’s relationship with the / French fashion industry had proved fractious. 2 For three of his 1930s productions, Samuel Goldwyn paid Coco Chanel $1 million to create costumes. After working with Gloria Swanson on 1931’s Tonight or Never, she severed her a more youthful mode, interpreting the free- “The biggest thing in my life was winning that relationship with the studio. -

'Perfect Fit': Industrial Strategies, Textual Negotiations and Celebrity

‘Perfect Fit’: Industrial Strategies, Textual Negotiations and Celebrity Culture in Fashion Television Helen Warner Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of East Anglia School of Film and Television Studies Submitted July 2010 ©This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author's prior, written consent. Helen Warner P a g e | 2 ABSTRACT According to the head of the American Costume Designers‟ Guild, Deborah Nadoolman Landis, fashion is emphatically „not costume‟. However, if this is the case, how do we approach costume in a television show like Sex and the City (1998-2004), which we know (via press articles and various other extra-textual materials) to be comprised of designer clothes? Once onscreen, are the clothes in Sex and the City to be interpreted as „costume‟, rather than „fashion‟? To be sure, it is important to tease out precise definitions of key terms, but to position fashion as the antithesis of costume is reductive. Landis‟ claim is based on the assumption that the purpose of costume is to tell a story. She thereby neglects to acknowledge that the audience may read certain costumes as fashion - which exists in a framework of discourses that can be located beyond the text. This is particularly relevant with regard to contemporary US television which, according to press reports, has witnessed an emergence of „fashion programming‟ - fictional programming with a narrative focus on fashion. -

English and French-Speaking Legislation Intended to Diminish the Rights Requiring Workers Contribute to Their Own Television Channels Throughout Canada

Join The Stand Up, Fight Back Campaign! IATSE Political Action Committee Voucher for Credit/Debit Card Deductions I hereby authorize the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, Moving Picture Technicians, Artists and Allied Crafts of the United States Political Action Committee, hereinafter called the IATSE-PAC to initiate a deduction from my credit card. This authorization is to remain in full force and effect until the IATSE-PAC has received written notification from me of its termination in such time and in such manner as to afford the parties a reasonable opportunity to act on it. Check one: President’s Club ($40.00/month) Leader’s Club ($20.00/month) Activist’s Club ($10.00/month) Choose one: Or authorize a monthly contribution of $________ Mastercard Discover Authorize a one-time contribution of $________($10.00 minimum) VISA American Express Card #: _____________________________________ Expiration Date (MM/YY): ____/____ Card Security Code: ______ Employee Signature_______________________________ Date________________ Last 4 Digits of SSN___________ Local Number_____________ ET Print Name_____________________________________Email______________________________________ Phone Number________________________ Home Address_______________________________________ City ____________________________ State/Zip Code _____________________________ Billing Address_________________________ City_________________ State/Zip Code______________ Occupation/Employer_____________________ This Authorization is voluntarily made based on my specific -

THE POLITICS of Fashion Throughout History, the First Lady’S Style Has Made a Statement

THE POLITICS OF Fashion Throughout history, the first lady’s style has made a statement By Johanna Neuman rom the beginning, we have obsessed new country’s more egalitarian inclinations. Martha about their clothes, reading into the Washington dressed simply, but her use of a gilded sartorial choices of America’s first la- coach to make social calls led critics to lament that dies the character of a nation and the she was acting like a queen. Abigail Adams, who had expression of our own ambitions. “We cultivated an appreciation for French fashion, was want them to reflect us but also to reflect glamour,” careful to moderate her tastes but failed to protect Fobserves author Carl Sferrazza Anthony, who has John Adams from criticism that he was a monarchist; studied fashion and the first ladies. “It is always he was defeated for re-election by Thomas Jefferson. said that Mamie Eisenhower reflected what many “These Founding Fathers had deep ancestral and in- Americans were, and Jackie Kennedy reflected what tellectual ties to countries where government lead- many American women wanted to be.” ers’ dress was explicitly understood to In a nation born in rebellion against Jackie Kennedy in Ottawa, reflect and represent their august posi- the king, the instinct among public fig- Canada, in an outfit tions,” says historian Caroline Weber, ures to dress regally clashed with the designed by Oleg Cassini author of Queen of Fashion: What PAUL SCHUTZER—TIME & LIFE PICTURES/GETTY IMAGES SPECIAL COLLECTOR’S EDITION 77 AMERICA’S FIRST LADIES Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution (2008). -

Jeanne Lanvin

JEANNE LANVIN A 01long history of success: the If one glances behind the imposing façade of Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, 22, in Paris, Lanvin fashion house is the oldest one will see a world full of history. For this is the Lanvin headquarters, the oldest couture in the world. The first creations house in the world. Founded by Jeanne Lanvin, who at the outset of her career could not by the later haute couture salon even afford to buy fabric for her creations. were simple clothes for children. Lanvin’s first contact with fashion came early in life—admittedly less out of creative passion than economic hardship. In order to help support her six younger siblings, Lanvin, then only fifteen, took a job with a tailor in the suburbs of Paris. In 1890, at twenty-seven, Lanvin took the daring leap into independence, though on a modest scale. Not far from the splendid head office of today, she rented two rooms in which, for lack of fabric, she at first made only hats. Since the severe children’s fashions of the turn of the century did not appeal to her, she tailored the clothing for her young daughter Marguerite herself: tunic dresses designed for easy movement (without tight corsets or starched collars) in colorful patterned cotton fabrics, generally adorned with elaborate smocking. The gentle Marguerite, later known as Marie-Blanche, was to become the Salon Lanvin’s first model. When walking JEANNE LANVIN on the street, other mothers asked Lanvin and her daughter from where the colorful loose dresses came. -

During the 1930-60'S, Hollywood Directors Were Told to "Put the Light Where the Money Is" and This Often Meant Spectacular Costumes

During the 1930-60's, Hollywood directors were told to "put the light where the money is" and this often meant spectacular costumes. Stuidos hired the biggest designers and fashion icons to bring to life the glitz and the glamour that moviegoers expected. Edith Head, Adrian, Walter Plunkett, Irene and Helen Rose were just a few that became household names because of their designs. In many cases, their creations were just as important as the plot of the movie itself. Few costumes from the "Golden Era" of Hollywood remain except for a small number tha have been meticulously preserved by a handful of collectors. Greg Schreiner is one of the most well-known. His wonderful Hollywood fiolm costume collection houses over 175 such masterpieces. Greg shares his collection in the show Hollywoood Revisited. Filled with music, memories and fun, the revue allows the audience to genuinely feel as if they were revisiting the days that made Hollywood a dream factory. The wardrobes of Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor, Julie Andrews, Robert Taylor, Bette Davis, Ann-Margret, Susan Hayward, Bob Hope and Judy Garland are just a few from the vast collection that dazzle the audience. Hollywood Revisited is much more than a visual treat. Acclaimed vocalists sing movie-related music while modeling the costumes. Schreiner, a professional musician, provides all the musical sccompaniment and anecdotes about the designer, the movie and scene for each costume. The show has won critical praise from movie buffs, film historians, and city-wide newspapers. Presentation at the legendary Pickfair, The State Theatre for The Los Angeles Conservancy and The Santa Barbara Biltmore Hotel met with huge success. -

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book. -

Press Release 2021 LVMH Prize for Young Fashion Designers: 8Th Edition Call for Applications

Press release 2021 LVMH Prize For Young Fashion Designers: 8th edition Call for applications Paris, 11th January 2021 The applications for the 8th edition of the LVMH Prize will open starting Monday 11th January 2021. They must be submitted exclusively on the Prize website: www.lvmhprize.com. Applications will close on Sunday 28th February 2021. It should be noted that, as a result of the health crisis that has imposed certain restrictions, the semi-final will this year, as an exception, take the form of a digital forum, to be held from Tuesday 6th April until Sunday 11th April 2021. This forum will enable each of our international Experts to discover and select on line the competing designers. Driven by a “passion for creativity”, LVMH launched the Prize in 2013. This patronage embodies the commitment of the Group and its Houses in favour of young designers. It is open to designers under 40 who have produced at least two collections of womenswear or menswear, or two genderless collections. Moreover, the Prize is international. It is open to designers from all over the world. The winner of the LVMH Prize for Young Fashion Designers enjoys a tailored mentorship and receives a 300,000-euro endowment. The LVMH teams mentor the winners in many fields, such as sustainable development, communication, copyright and corporate legal aspects, as well as marketing and the financial management of a brand. The winner of the Karl Lagerfeld / Special Jury Prize receives a 150,000-euro allocation and also enjoys a one-year mentorship. Furthermore, on the occasion of each edition, the Prize distinguishes three young fashion school graduates.