Conflict, Governance and Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (1MB)

Kunal KK and SK Mishra: Assuming Corporate responsibilities in Lawless Situations TWP105/2014-15 Assuming Corporate Responsibilities in Lawless Situations: Case Study of a News Media Organization by Kunal Kamal Kumar Assistant Professor T A Pai Management Institute (TAPMI) Manipal Manipal 576 104, Karnataka INDIA Phone: +91-9902494054 Email: [email protected] ; [email protected] and Sushanta Kumar Mishra Indian Institute of Management (IIM) Indore Indore 453 331, Madhya Pradesh INDIA Phone: +91-9752038027 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] TAPMI WORKING PAPERS KUNAL 1 Kunal KK and SK Mishra: Assuming Corporate responsibilities in Lawless Situations TWP105/2014-15 Assuming Corporate Responsibilities in Lawless Situations: Case Study of a News Media Organization In economies characterized by high levels of inequalities, there is a greater incentive for rich and powerful to manipulate public opinion through news media (Herman & Chomsky, 2002). As news media plays an important role in shaping people’s preferences and policy outcomes, it is luring for the rich to use it to their advantage (Petrova, 2008). The vast persuasive power of news media enthralls all: be it governments (Enikolopov, Petrova, & Zhuravskaya, 2011), non-government organizations (Zhang & Swartz, 2009), or business corporations (Gambaro & Puglisi, 2010; Reuter & Zitzewitz, 2006), each uses news media for furthering their causes (Schudson, 2003, pp. 16-32). Unfortunately, in economies with weak democratic institutions, the rich and the powerful use news media’s power of indoctrination of beliefs through selective or inaccurate information to further propel themselves up the ladder (Mcmillan & Zoido, 2004); in effect, deepening the inequality. Cross-institutional reality monitoring is a decisive feature of any society and news media plays a critical role in this monitoring process (Johnson, 1998, 2007). -

Access Jharkhand-Obj07-04-2021-E-Book

Index 01. Jharkhand Special Branch Constable (Close 16. JSSC Assistant Competitive Examination Cadre) Competitive Exam 01-09-2019 28.06.2015. 02. J.S.S.C. - Jharkhand Excise Constable Exam 17. Jharkhand Forest Guard Appointment Com- 04-08-2019 petitive (Prelims) Exam - 24.05.2015. 03. SSC IS (CKHT)-2017, Intermediate Level (For 18. Jharkhand Staff Selection Commission the post of Hindi Typing Noncommittee in Com- organized Women Supervisor competitive puter Knowledge and Computer) Joint Competi- Exam - 2014. tive Exam 19. Fifth Combined Civil Service Prelims Compet- 04. JUVNL Office Assistent Exam 10-03-2017 itive Exam - 15.12.2013. 05. J.S.S.C. - Post Graduate Exam 19-02-2017 20. Jharkhand Joint Secretariat Assistant (Mains) 06. J.S.S.C Amin Civil Resional Investigator Exam Examination 16.12.2012. 08-01-2017 21. State High School Teacher Appointment 07. JPSC Prelims Paper II (18.12.2016) Examination 29.08.2012. 08. JPSC Prelims Paper-I (Jharkhand Related 22. Jharkhand Limited Departmental Exam- Questions Only on 18.12.2016) 2012. 09. Combined Graduation Standard Competitive 23. Jharkhand Joint Secretariat Assistant Exam- (Prelims) Examinations 21.08.2016 2012. 10. Kakshpal appointment (mains) Competitive 24. Fourth Combined Civil Service (Prelims) Examination 10.07.2016. Competitive Examination - 2010. 11. Jharkhand Forest guard appointment (mains) 25. Government High School Teacher Appoint- Competitive Examination 16.05.2016. ment Exam - 2009. 12. JSSC Kakshpal Competitive (Prelims) Exam - 26. Primary Teacher Appointment Exam - 2008. 20.03.2016. 27. Third Combined Civil Service Prelims 13. Jharkhand Police Competitive Examination Competitive Exam - 2008. 30.01.2016. 28. JPSC Subsidiary Examination - 2007. -

AS5501 04 Wyatt India 33..47

Wyatt, A. (2015). India in 2014: Decisive National Elections. Asian Survey, 55(1), 33-47. https://doi.org/10.1525/AS.2015.55.1.33 Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.1525/AS.2015.55.1.33 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document Published as Wyatt, A. (2015). India in 2014: Decisive National Elections. Asian Survey, 55(1), 33-47. 10.1525/AS.2015.55.1.33. © [2015] by the Regents of the University of California. Copying and permissions notice: Authorization to copy this content beyond fair use (as specified in Sections 107 and 108 of the U. S. Copyright Law) for internal or personal use, or the internal or personal use of specific clients, is granted by the Regents of the University of California for libraries and other users, provided that they are registered with and pay the specified fee via Rightslink® or directly with the Copyright Clearance Center. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ ANDREW WYATT India in 2014 Decisive National Elections ABSTRACT The much anticipated general election produced a majority for the Bharatiya Janata Party under the leadership of Narendra Modi. The new administration is setting out an agenda for governing. The economy showed some signs of improvement, business confidence is returning, but economic growth has yet to return to earlier high levels. -

![2<U[Phb>__U^Aapxbx]V `Dtbcx^]B^]4E< EE](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3847/2-u-phb-u-aapxbx-v-dtbcx-b-4e-ee-1763847.webp)

2<U[Phb>__U^Aapxbx]V `Dtbcx^]B^]4E< EE

' ! 012 ! !" .$.$/ ()*+ ,*- 60 " + "#$$ %$#$$ ) %& *+, # %& )& )#) $ # 8 &9 "" #$$&$N $ ( &-O$& %/ # / ) 9 : / 31 1 ,* ,45 3 $621 !! #$ %&$%'()*!& he counting of votes for the TLok Sabha polls would be Q held on Thursday in the shad- ow of a raging controversy over security of the Electronic their franchise to elect 542 counting the slips at the end. Voting Machines (EVMs) and members of the Lok Sabha The poll body is also learnt " R charges that they were being from 8,049 contestants. to have decided to count postal rigged. The Election Election Commission offi- ballots simultaneously with with the EC, they cited rule Commission has rejected the cials said the counting of votes electronic voting machine 56(B). But the rule 56(D) says demand by 22 political parties will begin at 8 am on Thursday count due to the “sheer size” of ours after the Election for mandatory sample check of that voter verifiable paper audit and results are expected only by the ballots received this time HCommission (EC) on the VVPAT slips. Rule 56(B) trail (VVPAT) slips be matched late evening. from service voters. The count- Wednesday rejected demand and 56(D) are complete dif- with EVM data before count- For the first time in Lok ing will involve the matching of 22 Opposition parties for ferent things,” he said. ing of votes. Sabha polls, the EC will tally of VVPAT slips in five polling VVPAT slips’ check before the Reacting to the EC deci- The grueling and bitterly vote count on EVMs with voter booths picked at random for counting, the Opposition par- sion, CPI(M) general secretary fought seven-phase polls that verified paper audit trail slips each Assembly segment at the ties hit back saying the poll Sitaram Yechury tweeted, began on April 11 concluded in five polling stations in each end of counting. -

PRI Elections in Jharkhand: Making Women Count

38 PRI Elections in Jharkhand: Making Women Count SHACHI SETH Taking their place as representatives in PRIs, women in villages take the first step to strengthening rural populations by fighting for their rights and working towards development, self-sufficiency and equality As the oldest system of local governance in the nation, Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs) have held a traditional stronghold in the village life of India. Chiefly regarded as the space for conflict resolution and maintenance of order at the village level, these institutions were the receptacles of the Gandhian dream of Swaraj, or self- governance. As India embraced modernity in its institutions, PRIs were moulded to fit an agenda that went beyond mere arbitration and guidance. PRIs have undergone changes in terms of the process of choosing members, their duties and roles. In the current socio-political context, the chief objective of democratic states is development. Institutions of local governance, therefore, become crucial for addressing issues of the rural population, especially as decentralization becomes a buzzword in search of good governance. In Jharkhand, Panchayati Raj elections were held for the first time in 2011 although the state was formed in 2000. There was a surge in political participation by women and 56 per cent of the seats were won by women. The number of victorious women exceeded the 50 per cent that is reserved for them—a sign of encouragement for those working to better their lives. 39 The second elections, the results citizens, and to make choices The workshops of which were declared recently that benefit the community in conducted by PRADAN (2015), became an impetus the long run. -

FINAL PDF Offprint, AS5501 04 Wyatt India

Wyatt, A. (2015). India in 2014: Decisive National Elections. Asian Survey, 55(1), 33-47. https://doi.org/10.1525/AS.2015.55.1.33 Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.1525/AS.2015.55.1.33 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document Published as Wyatt, A. (2015). India in 2014: Decisive National Elections. Asian Survey, 55(1), 33-47. 10.1525/AS.2015.55.1.33. © [2015] by the Regents of the University of California. Copying and permissions notice: Authorization to copy this content beyond fair use (as specified in Sections 107 and 108 of the U. S. Copyright Law) for internal or personal use, or the internal or personal use of specific clients, is granted by the Regents of the University of California for libraries and other users, provided that they are registered with and pay the specified fee via Rightslink® or directly with the Copyright Clearance Center. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ ANDREW WYATT India in 2014 Decisive National Elections ABSTRACT The much anticipated general election produced a majority for the Bharatiya Janata Party under the leadership of Narendra Modi. The new administration is setting out an agenda for governing. The economy showed some signs of improvement, business confidence is returning, but economic growth has yet to return to earlier high levels. -

UZ W`C # U Z__Z Xd

9$ : ; ; ; (*+,(-'./! &'&'( !" #$"% : ' 35$-, 8<,$'/#,7: %/=<'73#4'+ ,+-3+8.<#'7 -':%+-8%#,7%/ /%#.-3/%3:8/ .-%# 34%/- %3$-<,,:,/ %%=>83$ 3#3# 3%#':,# ,-/% 8# -= ,/%% 032%=7% % ?+ . %&' (() !@A ?% , % # 0#1'23 '/4 #,7 ,+-3 he Government formation Tfor the BJP-led NDA (II) will be set in motion on Saturday with the newly-elect- ed MPs formally electing Narendra Modi as their leader in Parliament’s central hall. While the BJP has won 303 seats, the NDA has 352 mem- bers in the Lok Sabha. Modi is 8/%$ also expected to address the MPs following his election as massive fire engulfed a their leader. BJP Parliamentary Afour-storey commercial Party meeting will precede the complex in Surat on Friday, NDA meeting. killing at least 19 teenage stu- The Union Cabinet on dents at a coaching centre, Friday adopted a resolution many of whom jumped and fell recommending the dissolution to their deaths while some of the 16th Lok Sabha, making were suffocated, officials said. way for formal launch of the - ' . * In a video clip of the inci- + / ' ' process to form a new ' / ' ! " +, dent, some young students at ' " +, Government. President Ram the Takshashila Complex in Nath Kovind accepted the res- Many newcomers and With Finance Minister Sarthana area, where the build- Minister added. stranded students and other ignation of the Council of young faces could be part of the Arun Jaitley having health ing is located, can be seen Coaching classes at the occupants of the building. Ministers and asked Modi to second innings of the Modi issues, there have been talks jumping off the third and centre were run in a shade According to a fire offi- continue in office till the new Government. -

JMM, Congress Wins By-Poll, Retain Dumka and Bermo Assembly Seats

Jmm, Congress Wins By-Poll, Retain Dumka And Bermo Assembly Seats In Jharkhand Ranchi: Jharkhand Mukti Morcha (JMM) and Congress won the assembly by-poll in Jharkhand; retained Dumka and Bermo assembly seats. The JMM candidate Basant Soren defeated the BJP’s Lois Marandi in Dumka with around a margin of 6842 votes. While Kumar Jaimangal (Anup Singh) of Indian National Congress defeated Yogeshwar Mahto ‘Batul’ in Bermo assembly seat by 14225 votes. The by-elections in Jharkhand were necessitated after Hemant Soren vacated Dumka’s seat to retain his Barhait constituency. Soren contested the last assembly election on two seats and recorded victory on both seats. Meanwhile, Bermo’s seat got vacant after Rajendra Singh the sitting MLA, died due to health issues. Notably, Basant Soren is the younger brother of Chief Minister Hemant Soren, won the Dumka seat by more than 6500 votes. Jmm Chief Shifted To Medanta Hospital Gurugram For Treatment Ranchi: Jharkhand Mukti Morcha (JMM) chief Shibu Soren left for New Delhi for better treatment in Medanta Hospital, Gurugram on Tuesday. Around 4 pm, Soren left the Ranchi hospital in an ambulance to board the Bhubaneswar-New Delhi Rajdhani Express at Bokaro Steel City railway station. Soren (76) and his wife Rupi Soren were tested positive for coronavirus infection on 21 August. Later on, 24 August Soren admitted at Medanta Hospital Ranchi with complaints of shortness of breath. Chief Minister Hemant Soren accompanied his father to the railway station in Bokaro to see him off. ‘There is nothing to worry about,’ said Hemant Soren at Bokaro Steel City Railway station. -

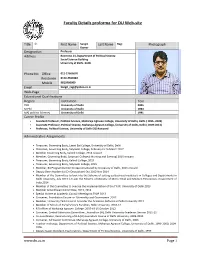

Faculty Details Proforma for DU Web-Site

Faculty Details proforma for DU Web-site Title Dr First Name Sangit Last Name Ragi Photograph Kumar Designation Professor Address Room No.14, Department of Political Science Social Science Building University of Delhi, Delhi Phone No Office 011-27666670 Residence 0120-4563984 Mobile 9810960009 Email [email protected] Web-Page Educational Qualifications Degree Institution Year PhD University of Delhi 2005 M Phil University of Delhi 1994 MA( political Science) University of Delhi 1991 Career Profile Assistant Professor, Political Science, Maharaja Agrasen College, University of Delhi, Delhi ( 1995- 2009) Associate Professor, Political Science, Maharaja Agrasen College, University of Delhi, Delhi ( 2009-2014) Professor, Political Science, University of Delhi 2014onward Administrative Assignments Treasurer, Governing Body, Laxmi Bai College, University of Delhi, Delhi Chairman, Governing Body, Satyavati College, February to 26 March 2017 Member Governing Body, Kalindi College, 2014 onward Member, Governing Body, Satyavati College,( Morning and Evening) 2015-onward Treasurer, Governing Body, Kalindi College, 2015 Treasurer, Governing Body, Satyavati College, 2015 Member, BA Programme Committee constituted by University of Delhi, 2015 onward Deputy Dean Academics (On Deputation) Oct 2012-Nov 2014 Member of the Committee to look into the Scheme of setting up Business Incubators in Colleges and Departments in Delhi University, July 2013 ( As per the Scheme of Ministry of Micro Small and Medium Enterprises, Government of India,2014 Member of the Committee to oversee the implementation of the FYUP, University of Delhi 2013 Member Anterdhwani Committee, 2013, 2014 Special Invitee at Academic Council Meeting on FYUP 2013 Convener, Foundation Course on Citizenship and Governance ,2012 Member, University Task Force to Consider the Academic Reforms in Delhi University 2012 Member of School of Social Science Faculties, Delhi University. -

Strong Showing by BJP in Maharashtra and Haryana

ISAS Insights No. 266 – 24 October 2014 Institute of South Asian Studies National University of Singapore 29 Heng Mui Keng Terrace #08-06 (Block B) Singapore 119620 Tel: (65) 6516 4239 Fax: (65) 6776 7505 www.isas.nus.edu.sg http://southasiandiaspora.org Strong Showing by BJP in Maharashtra and Haryana Ronojoy Sen1 The results of the latest Assembly elections in the Indian states of Maharashtra and Haryana have not come as a surprise. Given the performance of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in the two states in the 2014 national election, it was expected that the BJP would emerge as the single largest party in both states. But the number of seats won by the party and the decimation of the Congress, which was in power in both Maharashtra and Haryana, surprised many. In Maharashtra, the BJP, which contested on its own for the first time in 25 years, won 123 seats in the 288-member Assembly, up from 46 seats in 2009; in Haryana the jump was even more dramatic for the BJP from 4 out of 90 seats in 2009 to 47 seats. The decline for the Congress was equally steep. In Maharashtra the Congress’s seat tally nearly halved from 82 in 2009 to 42 while in Haryana it fell from 40 to 15. Since the BJP won an outright majority in Haryana, it has wasted no time in appointing Manohar Lal Khattar, a first-time MLA (Member of Legislative Assembly) and an active member of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), as Chief Minister. In Maharashtra the situation is more complicated with the BJP short of an outright majority. -

Amit Shah Addressing a Massive Election Rally in Garhwa, Jharkhand

@Kamal.Sandesh KamalSandeshLive www.kamalsandesh.org kamal.sandesh @KamalSandesh ‘VAJPAYEE GOVT. CREATED JHARKHAND, PM MODI TAKING IT FORWard’ Vol. 14, No. 24 16-31 December, 2019 (Fortnightly) `20 JHARKHAND ASSEMBLY ELECTION - 2019 ‘BJP WORKS FOR DEVELOPMENT OF EVERYONe’ 16-31 DECEMBER, 2019 I KAMAL SANDESH I 1 BJP National President & Union Minister Shri Amit Shah addressing a massive election rally in Garhwa, Jharkhand Tamilnadu BJP welcomes BJP National Working President BJP National Working President Shri JP Nadda paying tributes Shri JP Nadda on his arrival in Chennai. BJP National General to Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar on his Mahaparinirvan Secretary & Tamilnadu Prabhari Shri Muralidhar Rao also Diwas at B.R. Ambedkar Memorial, Alipur, New Delhi seen in the picture. Union Ministers Shri Rajnath Singh & Shri Nitin Gadkari join Union Minister Shri Rajnath Singh addressing a huge the family members of martyrs of 26/11 terorist attack to election rally in Madhupur, Jharkhand pay their tributes at Gateway of India in Mumbai 2 I KAMAL SANDESH I 16-31 DECEMBER, 2019 Fortnightly Magazine Editor Prabhat Jha Executive Editor Dr. Shiv Shakti Bakshi Associate Editors Ram Prasad Tripathy Vikash Anand Creative Editors Vikas Saini Mukesh Kumar Phone +91(11) 23381428 FAX +91(11) 23387887 BJP GOVERNMENT CLEARS THE PATH OF E-mail DEVELOPMENT IN JHARKHAND: MODI [email protected] Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi addressed two mega [email protected] 06 political rallies in Barhi and Bokaro, Jharkhand on 09... Website: www.kamalsandesh.org VAICHARIKI 12 VAJPAYEE GOVT. National Democrats, Democratic Socialists & National Socialists 18 CREATED JHARKHAND, SHRADHANJALI PM MODI TAKING IT KAMAL SANDESH editorial board member FORWARD: AMIT SHAH SATYAPAL passes away 22 Bharatiya Janata Party National INTERVIEW President and Union Home BJP will get advantage of good governance, transparency 10 BJP SWEEPS KARNATAKA Minister Shri Amit Shah .. -

LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version)

'l fOR RfFfRNCl: ONLY. Fourteenth Series, Vol. VIII, No. 16 Saturday, March 19, 2005 Phalguna 28, 1926 (Saka) LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version) Fourth Session (Fourteenth Lok Sabha) I,.tic .. (Vol. VIII contains Nos. 11 to 20) Gazett~' £t Debeto, Unit Parliament Libl ary f3 u ilding Room No. FS-025 BIOM 'G' A()C. No ....••.•. 7 ............ O.. N ....... If/ofL4!S::::- LOK SABHA S{CAETARIAT NEW DELHI Price : Rs. 50.00 EDITORIAL BOARD G.C. Malhotra Secretary-General Lok Sabha Kifan Sahni Principal Chief Editor Harnam Oass Takker Chief Editor Parmesh Kumar Sharma Senior Editor S.S. Chauhan Assistant Editor (ORIGINAL ENGLISH PROCEEDINGS INCLUDED IN ENGLISH VERSION AND ORIGINAL HINDI PROCEEDINGS INCLUDED IN HINDI VERSION WILL BE TREATED AS AUTHORITATIVE AND NOT THE TRANSLATION THEREOF) CONTENTS (Fourteenth Series, Vol. VIII, Fourth Session, 200511926 (Saka) No. 18, Saturday, March 18, 2OO5IPhaiguna 28, 1928 (Satat) SUBJECT COLUMNS MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT ....................................................................................................~ 1 STANDING COMMITTEE ON RURAL DEVELOPMENT Fifth to Eighth Reports .............. ................. ..................... ..... .................... ...................... .................... 1-2 BUSINESS OF THE HOUSE ....................... .............. ......... ........... ..................... .......... .......................... 3-4 ACTUARIES BILL. 2005 .......................................................................................................................... 5