Strong Showing by BJP in Maharashtra and Haryana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

India's Democracy at 70: Toward a Hindu State?

India’s Democracy at 70: Toward a Hindu State? Christophe Jaffrelot Journal of Democracy, Volume 28, Number 3, July 2017, pp. 52-63 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2017.0044 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/664166 [ Access provided at 11 Dec 2020 03:02 GMT from Cline Library at Northern Arizona University ] Jaffrelot.NEW saved by RB from author’s email dated 3/30/17; 5,890 words, includ- ing notes. No figures; TXT created from NEW by PJC, 4/14/17 (4,446 words); MP ed- its to TXT by PJC, 4/19/17 (4,631 words). AAS saved by BK on 4/25/17; FIN created from AAS by PJC, 5/26/17 (5,018 words). FIN saved by BK on 5/2/17 (5,027 words); PJC edits as per author’s updates saved as FINtc, 6/8/17, PJC (5,308 words). PGS created by BK on 6/9/17. India’s Democracy at 70 TOWARD A HINDU STATE? Christophe Jaffrelot Christophe Jaffrelot is senior research fellow at the Centre d’études et de recherches internationales (CERI) at Sciences Po in Paris, and director of research at the Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS). His books include Religion, Caste, and Politics in India (2011). In 1976, India’s Constitution of 1950 was amended to enshrine secular- ism. Several portions of the original constitutional text already reflected this principle. Article 15 bans discrimination on religious grounds, while Article 25 recognizes freedom of conscience as well as “the right freely to profess, practise and propagate religion.” Collective as well as indi- vidual rights receive constitutional recognition. -

Mahead-Dec2019.Pdf

MAHAPARINIRVAN DAY 550TH BIRTH ANNIVERSARY: GURU NANAK DEV CLIMATE CHANGE VS AGRICULTURE VOL.8 ISSUE 11 NOVEMBER–DECEMBER 2019 ` 50 PAGES 52 Prosperous Maharashtra Our Vision Pahawa Vitthal A Warkari couple wishes Chief Minister Uddhav Thackeray after taking oath as the Chief Minister of Maharashtra. (Pahawa Vitthal is a pictorial book by Uddhav Thackeray depicting the culture and rural life of Maharashtra.) CONTENTS What’s Inside 06 THIS IS THE MOMENT The evening of the 28th November 2019 will be long remem- bered as a special evening in the history of Shivaji Park of Mumbai. The ground had witnessed many historic moments in the past with people thronging to listen to Shiv Sena Pramukh, Late Balasaheb Thackeray, and Udhhav Thackeray. This time, when Uddhav Thackeray took the oath as the Chief Minister of Maharashtra on this very ground, the entire place was once again charged with enthusiasm and emotions, with fulfilment seen in every gleaming eye and ecstasy on every face. Maharashtra Ahead brings you special articles on the new Chief Minister of Maharashtra, his journey as a politi- cian, the new Ministers, the State Government's roadmap to building New Maharashtra, and the newly elected members of the Maharashtra Legislative Assembly. 44 36 MAHARASHTRA TOURISM IMPRESSES THE BEACON OF LONDON KNOWLEDGE Maharashtra Tourism participated in the recent Bharat Ratna World Travel Market exhibition in London. A Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar platform to meet the world, the event helped believed that books the Department reach out to tourists and brought meaning to life. tourism-related professionals and inform them He had to suffer and about the tourism attractions and facilities the overcome acute sorrow State has. -

Download (1MB)

Kunal KK and SK Mishra: Assuming Corporate responsibilities in Lawless Situations TWP105/2014-15 Assuming Corporate Responsibilities in Lawless Situations: Case Study of a News Media Organization by Kunal Kamal Kumar Assistant Professor T A Pai Management Institute (TAPMI) Manipal Manipal 576 104, Karnataka INDIA Phone: +91-9902494054 Email: [email protected] ; [email protected] and Sushanta Kumar Mishra Indian Institute of Management (IIM) Indore Indore 453 331, Madhya Pradesh INDIA Phone: +91-9752038027 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] TAPMI WORKING PAPERS KUNAL 1 Kunal KK and SK Mishra: Assuming Corporate responsibilities in Lawless Situations TWP105/2014-15 Assuming Corporate Responsibilities in Lawless Situations: Case Study of a News Media Organization In economies characterized by high levels of inequalities, there is a greater incentive for rich and powerful to manipulate public opinion through news media (Herman & Chomsky, 2002). As news media plays an important role in shaping people’s preferences and policy outcomes, it is luring for the rich to use it to their advantage (Petrova, 2008). The vast persuasive power of news media enthralls all: be it governments (Enikolopov, Petrova, & Zhuravskaya, 2011), non-government organizations (Zhang & Swartz, 2009), or business corporations (Gambaro & Puglisi, 2010; Reuter & Zitzewitz, 2006), each uses news media for furthering their causes (Schudson, 2003, pp. 16-32). Unfortunately, in economies with weak democratic institutions, the rich and the powerful use news media’s power of indoctrination of beliefs through selective or inaccurate information to further propel themselves up the ladder (Mcmillan & Zoido, 2004); in effect, deepening the inequality. Cross-institutional reality monitoring is a decisive feature of any society and news media plays a critical role in this monitoring process (Johnson, 1998, 2007). -

Government of India Ministry of External Affairs Rajya

01/06/2019 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF EXTERNAL AFFAIRS RAJYA SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO-2568 ANSWERED ON-09.08.2018 Permission for State Ministers to visit China 2568 Shri Ritabrata Banerjee . (a) whether it is a fact that Government is not allowing elected Chief Ministers and other Cabinet Ministers of State Governments to go on a visit to China; (b) if so, the details thereof, State-wise and if not, the reasons therefor; and (c) the details of Chief Ministers and other State Ministers visiting China during the last three years? ANSWER (a) to (c) There are no restrictions on the travel of Chief Ministers and Ministers of State Governments to the People’s Republic of China. On the contrary, under an institutional arrangement between Ministry of External Affairs and the International Department of the Communist Party of China, visits of Chief Ministers of Indian States to China are proactively facilitated in order to promote contacts at the level of provincial leaders and with senior functionaries of the Communist Party of China. Among the Chief Ministers and Ministers of our States, who have visited China since 2015, include: Chief Ministers: S. No. State Minister Period of Visit 1. Andhra Pradesh Shri N. Chandrababu Naidu April 2015 2. Gujarat Smt. Anandiben Patel May 2015 3. Maharashtra Shri Devendra Fadnavis May 2015 4. Telangana Shri K. Chandrashekhar Rao September 2015 5. Haryana Shri Manohar Lal Khattar January 2016 6. Chhattisgarh Shri Raman Singh April 2016 7. Andhra Pradesh Shri N. Chandrababu Naidu June 2016 8. Madhya Pradesh Shri Shivraj Singh Chouhan June 2016 Ministers of States: S. -

List of Chief Ministers Bombay and Maharashtra No Name Term of Office Party Days in Office Chief Ministers of Bombay State 1 B. G

List of Chief Ministers Bombay and Maharashtra No Name Term of office Party Days in office Chief Ministers of Bombay State 1 B. G. Kher 15 August 1947 21 April 1952 1711 Days Morarji Desai 21 April 1952 31 October 1956 1654 Days 2 MLA for Bulsar Chikhli Indian National Congress Yashwantrao Chavan 1 November 1956 5 April 1957 1307 Days 3 MLA for Karad North 5 April 1957 30 April 1960 Chief Ministers of Maharashtra Yashwantrao Chavan 1 May 1960 19 November 1962 933 Days 1 MLA for Karad North Marotrao Kannamwar 20 November 1962 24 November 1963 370 Days 2 MLA for Saoli P. K. Sawant 25 November 1963 4 December 1963 10 Days 3 MLA for Chiplun 5 December 1963 1 March 1967 1548 Days Indian National Congress Vasantrao Naik 1 March 1967 13 March 1972 1840 Days MLA for Pusad 4 13 March 1972 20 February 1975 709 Days [Total 4097 Days] Shankarrao Chavan 21 February 1975 16 May 1977 816 Days 5 MLA for Bhokar 17 May 1977 5 March 1978 293 Days Vasantdada Patil 6 5 March 1978 18 July 1978 134 Days Sharad Pawar 18 July 1978 17 February 1980 Progressive Democratic Front 580 Days 7 MLA for Baramati Vacant 17 February 1980 8 June 1980 N/A 113 Days - (President's rule) Abdul Rehman Antulay 9 June 1980 12 January 1982 583 Days 8 MLA for Shrivardhan Babasaheb Bhosale 21 January 1982 1 February 1983 377 Days 9 MLA for Nehrunagar 6 Vasantdada Patil 2 February 1983 1 June 1985 851 Days [Total 1304 Days] Shivajirao Patil Nilangekar 3 June 1985 6 March 1986 277 Days 10 MLA for Nilanga Indian National Congress 5 Shankarrao Chavan 12 March 1986 26 June 1988 837 Days -

STATEMENTS by MINISTERS (I) the Following Statements Were Made by Ministers During the Session: —

STATEMENTS BY MINISTERS (I) The following Statements were made by Ministers during the Session: — Sl. Date Subject matter of the Statement Name of the Minister Time taken No. Hrs.Mts. 1. 07-07-2009 Anniversary of the attack on Indian Embassy in Shri S.M. Krishna 0-08 Kabul on the 7th July, 2008. 2. 09-07-2009 Significant developments in our neighbourhood. -do- 0-56 3. 14-07-2009 Accident at Delhi Metro site on the 12th July, Shri Saugata Ray 0-35 2009. 4. 17-07-2009 Regarding recent visits to Italy, France and Egypt. Dr. Manmohan Singh, 0-22 Prime Minister 5. 21-07-2009 Recent visit to India by the Secretary of State of Shri S.M. Krishna 0-39 the United States of America, Ms. Hillary Clinton. 6. 28-07-2009 Decisions taken by the board of Delhi Metro Rail Shri S. Jaipal Reddy 0-26 Corporation (DMRC) on the basis of the report of high-level committee that enquired into the accident at the DMRC construction site on the 12th of July, 2009. 7. 31-07-2009 Import of raw and white/refined sugar. Shri Sharad Pawar 0-40 06-08-2009 (II) The following Statements were laid by Ministers on the Table of the House during the Session: — Sl. Date Subject matter of the Statement Name of the Minister Time taken No. Hrs.Mts. 1. 10-07-2009 Status of implementation of recommendations Shri Srikant Jena 0-01 contained in the Twenty-seventh Report of the Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committee on Chemicals and Fertilizers, 2008-09. -

Access Jharkhand-Obj07-04-2021-E-Book

Index 01. Jharkhand Special Branch Constable (Close 16. JSSC Assistant Competitive Examination Cadre) Competitive Exam 01-09-2019 28.06.2015. 02. J.S.S.C. - Jharkhand Excise Constable Exam 17. Jharkhand Forest Guard Appointment Com- 04-08-2019 petitive (Prelims) Exam - 24.05.2015. 03. SSC IS (CKHT)-2017, Intermediate Level (For 18. Jharkhand Staff Selection Commission the post of Hindi Typing Noncommittee in Com- organized Women Supervisor competitive puter Knowledge and Computer) Joint Competi- Exam - 2014. tive Exam 19. Fifth Combined Civil Service Prelims Compet- 04. JUVNL Office Assistent Exam 10-03-2017 itive Exam - 15.12.2013. 05. J.S.S.C. - Post Graduate Exam 19-02-2017 20. Jharkhand Joint Secretariat Assistant (Mains) 06. J.S.S.C Amin Civil Resional Investigator Exam Examination 16.12.2012. 08-01-2017 21. State High School Teacher Appointment 07. JPSC Prelims Paper II (18.12.2016) Examination 29.08.2012. 08. JPSC Prelims Paper-I (Jharkhand Related 22. Jharkhand Limited Departmental Exam- Questions Only on 18.12.2016) 2012. 09. Combined Graduation Standard Competitive 23. Jharkhand Joint Secretariat Assistant Exam- (Prelims) Examinations 21.08.2016 2012. 10. Kakshpal appointment (mains) Competitive 24. Fourth Combined Civil Service (Prelims) Examination 10.07.2016. Competitive Examination - 2010. 11. Jharkhand Forest guard appointment (mains) 25. Government High School Teacher Appoint- Competitive Examination 16.05.2016. ment Exam - 2009. 12. JSSC Kakshpal Competitive (Prelims) Exam - 26. Primary Teacher Appointment Exam - 2008. 20.03.2016. 27. Third Combined Civil Service Prelims 13. Jharkhand Police Competitive Examination Competitive Exam - 2008. 30.01.2016. 28. JPSC Subsidiary Examination - 2007. -

YEARS of India Rebuilding

PM NAGPUR VISIT n DIALOGUE: CHIEF MINISTER n NITI AAYOG MEETING n ASIATIC SOCIETY VOL.6 ISSUE 05 n M AY 2017 n `50 n PAGES 52 YEARS OF REBUILDING INDIA PRIORITY Maharashtra A TRUSTED DESTINATION Prime Minister Narendra Modi has made all efforts to focus on the development of Maharashtra. The State has not just got support from him, but has also been a platform to launch and celebrate his initiatives 1 2 3 4 5 1. Prime Minister Narendra Modi performing jalpoojan of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj memorial; 2. The Prime Minister with Pune girl Vaishali Yadav; 3. The Prime Minister at the Make in India Week; 4. The Prime Minister with Governor Ch. Vidyasagar Rao, Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis and other dignitaries at the Smart Cities function in Pune; 5. The Prime Minister inaugurates GE facility at Chakan; 6. The Prime Minister at the signing of MIDC and TwinStar Display Technologies MoU; 7. The Prime Minister performing bhoomipujan of Dr 6 Ambedkar memorial at Indu Mill 7 CONTENTS What’s Inside 05 Column DEVENDRA FADNAVIS The Chief Minister of Maharashtra writes on the three years of the Union Government led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi. In these three years, the country has steadily transformed into a nation that is competent, enabled and fully geared to face challenges confidently and emerge as a global power. The time was also good for States like Maharashtra that recieved immense support, guidance, global opportunities and welfare programmes dedicated to various sections to build an inclusive society 09 COLUMN 12 COLUMN 14 COLUMN -

Megacity Security Conference Speaker and Participant Bios

Megacity Security Conference Monday, November 22, 2015 – Tuesday, November 23, 2015 Speaker and Participant Bios Mumbai, India Gov. John M. Hunstman, Jr. Former Governor of Utah; Former Ambassador to China; Chairman, Atlantic Council Governor Jon M. Huntsman, Jr. is Chairman of the Atlantic Council Board of Directors. He began his career in public service as a Staff Assistant to President Ronald Reagan. He has served each of the four US presidents since then in critical roles around the world, including as Ambassador to Singapore, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Asia, US Trade Ambassador, and most recently, US Ambassador to China. In all three Senate confirmations, he received unanimous votes. Twice elected Governor of Utah, Governor Huntsman brought about strong economic reforms, tripled the state's rainy day fund, and helped bring unemployment rates to historic lows. During his tenure, Utah was named the best managed state in America. Recognized by others for his service, Governor Huntsman was elected as Chairman of the Western Governors Association, serving nineteen states throughout the region. He currently serves on the boards of Ford Motor Company, Caterpillar Corporation, Chevron Corporation, Huntsman Corporation, the US Naval Academy Foundation, and the University of Pennsylvania. In addition, he serves as a Distinguished Fellow at the Brookings Institute, a Trustee of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a Trustee of the Reagan Presidential Foundation, and Chairman of the Huntsman Cancer Foundation. Governor Huntsman has served as a Visiting Fellow at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government as well as a Distinguished Lecturer at Duke University's Sanford School of Public Policy. -

Maharashtra Vidhan Sabha Candidate List.Xlsx

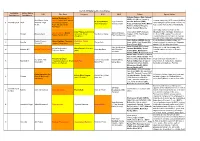

List of All Maharashtra Candidates Lok Sabha Vidhan Sabha BJP Shiv Sena Congress NCP MNS Others Special Notes Constituency Constituency Vishram Padam, (Raju Jaiswal) Aaditya Thackeray (Sunil (BSP), Adv. Mitesh Varshney, Sunil Rane, Smita Shinde, Sachin Ahir, Ashish Coastal road (kolis), BDD chawls (MHADA Dr. Suresh Mane Vijay Kudtarkar, Gautam Gaikwad (VBA), 1 Mumbai South Worli Ambekar, Arjun Chemburkar, Kishori rules changed to allow forced eviction), No (Kiran Pawaskar) Sanjay Jamdar Prateep Hawaldar (PJP), Milind Meghe Pednekar, Snehalata ICU nearby, Markets for selling products. Kamble (National Peoples Ambekar) Party), Santosh Bansode Sewri Jetty construction as it is in a Uday Phanasekar (Manoj Vijay Jadhav (BSP), Narayan dicapitated state, Shortage of doctors at Ajay Choudhary (Dagdu Santosh Nalaode, 2 Shivadi Shalaka Salvi Jamsutkar, Smita Nandkumar Katkar Ghagare (CPI), Chandrakant the Sewri GTB hospital, Protection of Sakpal, Sachin Ahir) Bala Nandgaonkar Choudhari) Desai (CPI) coastal habitat and flamingo's in the area, Mumbai Trans Harbor Link construction. Waris Pathan (AIMIM), Geeta Illegal buildings, building collapses in Madhu Chavan, Yamini Jadhav (Yashwant Madhukar Chavan 3 Byculla Sanjay Naik Gawli (ABS), Rais Shaikh (SP), chawls, protests by residents of Nagpada Shaina NC Jadhav, Sachin Ahir) (Anna) Pravin Pawar (BSP) against BMC building demolitions Abhat Kathale (NYP), Arjun Adv. Archit Jaykar, Swing vote, residents unhappy with Arvind Dudhwadkar, Heera Devasi (Susieben Jadhav (BHAMPA), Vishal 4 Malabar Hill Mangal -

AS5501 04 Wyatt India 33..47

Wyatt, A. (2015). India in 2014: Decisive National Elections. Asian Survey, 55(1), 33-47. https://doi.org/10.1525/AS.2015.55.1.33 Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.1525/AS.2015.55.1.33 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document Published as Wyatt, A. (2015). India in 2014: Decisive National Elections. Asian Survey, 55(1), 33-47. 10.1525/AS.2015.55.1.33. © [2015] by the Regents of the University of California. Copying and permissions notice: Authorization to copy this content beyond fair use (as specified in Sections 107 and 108 of the U. S. Copyright Law) for internal or personal use, or the internal or personal use of specific clients, is granted by the Regents of the University of California for libraries and other users, provided that they are registered with and pay the specified fee via Rightslink® or directly with the Copyright Clearance Center. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ ANDREW WYATT India in 2014 Decisive National Elections ABSTRACT The much anticipated general election produced a majority for the Bharatiya Janata Party under the leadership of Narendra Modi. The new administration is setting out an agenda for governing. The economy showed some signs of improvement, business confidence is returning, but economic growth has yet to return to earlier high levels. -

![2<U[Phb>__U^Aapxbx]V `Dtbcx^]B^]4E< EE](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3847/2-u-phb-u-aapxbx-v-dtbcx-b-4e-ee-1763847.webp)

2<U[Phb>__U^Aapxbx]V `Dtbcx^]B^]4E< EE

' ! 012 ! !" .$.$/ ()*+ ,*- 60 " + "#$$ %$#$$ ) %& *+, # %& )& )#) $ # 8 &9 "" #$$&$N $ ( &-O$& %/ # / ) 9 : / 31 1 ,* ,45 3 $621 !! #$ %&$%'()*!& he counting of votes for the TLok Sabha polls would be Q held on Thursday in the shad- ow of a raging controversy over security of the Electronic their franchise to elect 542 counting the slips at the end. Voting Machines (EVMs) and members of the Lok Sabha The poll body is also learnt " R charges that they were being from 8,049 contestants. to have decided to count postal rigged. The Election Election Commission offi- ballots simultaneously with with the EC, they cited rule Commission has rejected the cials said the counting of votes electronic voting machine 56(B). But the rule 56(D) says demand by 22 political parties will begin at 8 am on Thursday count due to the “sheer size” of ours after the Election for mandatory sample check of that voter verifiable paper audit and results are expected only by the ballots received this time HCommission (EC) on the VVPAT slips. Rule 56(B) trail (VVPAT) slips be matched late evening. from service voters. The count- Wednesday rejected demand and 56(D) are complete dif- with EVM data before count- For the first time in Lok ing will involve the matching of 22 Opposition parties for ferent things,” he said. ing of votes. Sabha polls, the EC will tally of VVPAT slips in five polling VVPAT slips’ check before the Reacting to the EC deci- The grueling and bitterly vote count on EVMs with voter booths picked at random for counting, the Opposition par- sion, CPI(M) general secretary fought seven-phase polls that verified paper audit trail slips each Assembly segment at the ties hit back saying the poll Sitaram Yechury tweeted, began on April 11 concluded in five polling stations in each end of counting.