Provided by the Author(S) and University College Dublin Library in Accordance with Publisher Policies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ballinleenty Townland, Co. Tipperary

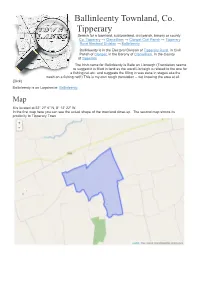

Ballinleenty Townland, Co. Tipperary Search for a townland, subtownland, civil parish, barony or countySearch Co. Tipperary → Clanwilliam → Clonpet Civil Parish → Tipperary Rural Electoral Division → Ballinleenty Ballinleenty is in the Electoral Division of Tipperary Rural, in Civil Parish of Clonpet, in the Barony of Clanwilliam, in the County of Tipperary The Irish name for Ballinleenty is Baile an Líontaigh (Translation seems to suggest it is filled in land as the word Líontaigh is related to the one for a fishing net etc. and suggests the filling in was done in stages aka the mesh on a fishing net!!) This is my own rough translation – not knowing the area at all. (Dick) Ballinleenty is on Logainm.ie: Ballinleenty. Map It is located at 52° 27' 6" N, 8° 12' 22" W. In the first map here you can see the actual shape of the townland close-up. The second map shows its proximity to Tipperary Town Leaflet | Map data © OpenStreetMap contributors Area Ballinleenty has an area of: 1,513,049 m² / 151.30 hectares / 1.5130 km² 0.58 square miles 373.88 acres / 373 acres, 3 roods, 21 perches Nationwide, it is the 17764th largest townland that we know about Within Co. Tipperary, it is the 933rd largest townland Borders Ballinleenty borders the following other townlands: Ardavullane to the west Ardloman to the south Ballynahow to the west Breansha Beg to the east Clonpet to the east Gortagowlane to the north Killea to the south Lackantedane to the east Rathkea to the west Subtownlands We don't know about any subtownlands in Ballinleenty. -

Appendix A16.8 Townland Boundaries to Be Crossed by the Proposed Project

Environmental Impact Assessment Report: Volume 3 Part B of 6 Appendix A16.8 Townland Boundaries to be Crossed by the Proposed Project TB No.: 1 Townlands: Abbotstown/ Dunsink Parish: Castleknock Barony: Castleknock NGR: 309268, 238784 Description: This townland boundary is marked at the same location on all the OS map editions. It is formed by a road, which today have been truncated by the M50 to the south-east. The tarmac surface of the road is still present at this location, although overgrown. The road also separated the demesne associated with Abbotstown House and Hillbrook (DL 1, DL 2). Reference: OS mapping, field inspection TB No.: 2 Townlands: Dunsink/ Sheephill Parish: Castleknock Barony: Castleknock NGR: 309327, 238835 Description: This townland boundary is marked at the same location on all the OS map editions. It is formed by a road, which today have been truncated by the M50 to the south-east. The tarmac surface of the road is still present at this location, although overgrown. The road also separated the demesne associated with Abbotstown House (within the townland of Sheephill) and Hillbrook (DL 1, DL 2). The remains of a stone demesne wall associated with Abbotstown are located along the northern side of the road (UBH 2). Reference: OS mapping, field inspection 32102902/EIAR/3B Environmental Impact Assessment Report: Volume 3 Part B of 6 TB No.: 3 Townlands: Sheephill/ Dunsink Parish: Castleknock Barony: Castleknock NGR: 310153, 239339 Description: This townland boundary is marked at the same location on all the OS map editions. It is formed by a road, which today have been truncated by the M50 to the south. -

![County Londonderry - Official Townlands: Administrative Divisions [Sorted by Townland]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6319/county-londonderry-official-townlands-administrative-divisions-sorted-by-townland-216319.webp)

County Londonderry - Official Townlands: Administrative Divisions [Sorted by Townland]

County Londonderry - Official Townlands: Administrative Divisions [Sorted by Townland] Record O.S. Sheet Townland Civil Parish Barony Poor Law Union/ Dispensary /Local District Electoral Division [DED] 1911 D.E.D after c.1921 No. No. Superintendent Registrar's District Registrar's District 1 11, 18 Aghadowey Aghadowey Coleraine Coleraine Aghadowey Aghadowey Aghadowey 2 42 Aghagaskin Magherafelt Loughinsholin Magherafelt Magherafelt Magherafelt Aghagaskin 3 17 Aghansillagh Balteagh Keenaght Limavady Limavady Lislane Lislane 4 22, 23, 28, 29 Alla Lower Cumber Upper Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Claudy Claudy 5 22, 28 Alla Upper Cumber Upper Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Claudy Claudy 6 28, 29 Altaghoney Cumber Upper Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Ballymullins Ballymullins 7 17, 18 Altduff Errigal Coleraine Coleraine Garvagh Glenkeen Glenkeen 8 6 Altibrian Formoyle / Dunboe Coleraine Coleraine Articlave Downhill Downhill 9 6 Altikeeragh Dunboe Coleraine Coleraine Articlave Downhill Downhill 10 29, 30 Altinure Lower Learmount / Banagher Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Banagher Banagher 11 29, 30 Altinure Upper Learmount / Banagher Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Banagher Banagher 12 20 Altnagelvin Clondermot Tirkeeran Londonderry Waterside Rural [Glendermot Waterside Waterside until 1899] 13 41 Annagh and Moneysterlin Desertmartin Loughinsholin Magherafelt Magherafelt Desertmartin Desertmartin 14 42 Annaghmore Magherafelt Loughinsholin Magherafelt Bellaghy Castledawson Castledawson 15 48 Annahavil Arboe Loughinsholin Magherafelt Moneymore Moneyhaw -

Chapter 15 Town and Village Plans / Rural Nodes

Town and Village Plans / Settlement Boundaries CHAPTER 15 TOWN AND VILLAGE PLANS / RURAL NODES Draft Carlow County Development Plan 2022-2028 345 | P a g e Town and Village Plans / Settlement Boundaries Chapter 15 Town and Village Plans / Rural Nodes 15.0 Introduction Towns, villages and rural nodes throughout strategy objectives to ensure the sustainable the County have a key economic and social development of County Carlow over the Plan function within the settlement hierarchy of period. County Carlow. The settlement strategy seeks to support the sustainable growth of these Landuse zonings, policies and objectives as settlements ensuring growth occurs in a contained in this Chapter should be read in sustainable manner, supporting and conjunction with all other Chapters, policies facilitating local employment opportunities and objectives as applicable throughout this and economic activity while maintaining the Plan. In accordance with Section 10(8) of the unique character and natural assets of these Planning and Development Act 2000 (as areas. amended) it should be noted that there shall be no presumption in law that any land zoned The Settlement Hierarchy for County Carlow is in this development plan (including any outlined hereunder and is contained in variation thereof) shall remain so zoned in any Chapter 2 (Table 2.1). Chapter 2 details the subsequent development plan. strategic aims of the core strategy together with settlement hierarchy policies and core Settlement Settlement Description Settlements Tier Typology 1 Key Town Large population scale urban centre functioning as self – Carlow Town sustaining regional drivers. Strategically located urban center with accessibility and significant influence in a sub- regional context. -

Commodore John Barry

Commodore John Barry Day, 13th September Commodore John Barry (1745-1803) a native of County Wexford, Ireland was a Continental Navy hero of the American War for Independence. Barry’s many victories at sea during the Revolution were important to the morale of the Patriots as well as to the successful prosecution of the War. When the First Congress, acting under the new Constitution of the United States, authorized the raising and construction of the United States Navy, President George Washington turned to Barry to build and lead the nation’s new US Navy, the successor to the Continental Navy. On 22 February 1797, President Washington conferred upon Barry, with the advice and consent of the Senate, the rank of Captain with “Commission No. 1,” United States Navy, effective 7 June 1794. Barry supervised the construction of his own flagship, the USS UNITED STATES. As commander of the first United States naval squadron under the Constitution, which included the USS CONSTITUTION (“Old Ironsides”), Barry was a Commodore with the right to fly a broad pennant, which made him a flag officer. Commodore John Barry By Gilbert Stuart (1801) John Barry served as the senior officer of the United States Navy, with the title of “Commodore” (in official correspondence) under Presidents George Washington, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. The ships built by Barry, and the captains selected, as well as the officers trained, by him, constituted the United States Navy that performed outstanding service in the “Quasi-War” with France, in battles with the Barbary Pirates and in America’s Second War for Independence (the War of 1812). -

A1a13os Mo1je3 A11110 1Eujnor

§Gllt,I IISSI Nlltllf NPIIII eq:101Jeq1eq3.epueas uuewnq3 Jeqqea1s1JI A1a13os Mo1Je3 PIO a11110 1euJnor SPONSORS ROYAL HOTEL - 9-13 DUBLIN STREET SOTHERN AUCTIONEERS LTD A Personal Hotel ofQuality Auctioneers. Valuers, Insurance Brokers, 30 Bedrooms En Suite, choice ofthree Conference Rooms. 37 DUBLIN STREET, CARLOW. Phone: 0503/31218. Fax.0503 43765 Weddings, functions, Dinner Dances, Private Parties. District Office: Irish Nationwide Building Society Food Served ALL Day. Phone: 0503/31621 FLY ONTO ED. HAUGHNEY & SON, LTD O'CONNOR'S GREEN DRAKE INN, BORRIS Fuel Merchant, Authorised Ergas Stockists Lounge and Restaurant - Lunches and Evening Meals POLLERTON ROAD, CARLOW. Phone: 0503/31367 Weddings and Parties catered for. GACH RATH AR CARLOVIANA IRISH PERMANENT PLC. ST. MARY'S ACADEMY 122/3 TULLOW STREET, CARLOW CARLOW Phone:0503/43025,43690 Seamus Walker - Manager Carlow DEERPARK SERVICE STATION FIRST NATIONAL BUILDING SOCIETY MARKET CROSS, CARLOW Tyre Service and Accessories Phone: 0503/42925, 42629 DUBLIN ROAD, CARLOW. Phone: 0503/31414 THOMAS F. KEHOE MULLARKEY INSURANCES Specialist Lifestock Auctioneer and Valuer, Farm Sales and Lettings COURT PLACE, CARLOW Property and Estate Agent Phone: 0503/42295, 42920 Agent for the Irish Civil Service Building Society General Insurance - Life and Pensions - Investment Bonds 57 DUBLIN STREET CARLOW. Telephone: 0503/31378/31963 Jones Business Systems GIFTS GALORE FROM Sales and Service GILLESPIES Photocopiers * Cash Registers * Electronic Weighing Scales KENNEDY AVENUE, CARLOW Car Phones * Fax Machines * Office Furniture* Computer/Software Burrin Street, Carlow. Tel: (0503) 32595 Fax (0503) 43121 Phone: 0503/31647, 42451 CARLOW PRINTING CO. LTD DEVOY'S GARAGE STRAWHALL INDUSTRIAL ESTATE, CARLOW TULLOW ROAD, CARLOW For ALL your Printing Requirements. -

Ulster-Scots

Ulster-Scots Biographies 2 Contents 1 Introduction The ‘founding fathers’ of the Ulster-Scots Sir Hugh Montgomery (1560-1636) 2 Sir James Hamilton (1559-1644) Major landowning families The Colvilles 3 The Stewarts The Blackwoods The Montgomerys Lady Elizabeth Montgomery 4 Hugh Montgomery, 2nd Viscount Sir James Montgomery of Rosemount Lady Jean Alexander/Montgomery William Montgomery of Rosemount Notable individuals and families Patrick Montgomery 5 The Shaws The Coopers James Traill David Boyd The Ross family Bishops and ministers Robert Blair 6 Robert Cunningham Robert Echlin James Hamilton Henry Leslie John Livingstone David McGill John MacLellan 7 Researching your Ulster-Scots roots www.northdowntourism.com www.visitstrangfordlough.co.uk This publication sets out biographies of some of the part. Anyone interested in researching their roots in 3 most prominent individuals in the early Ulster-Scots the region may refer to the short guide included at story of the Ards and north Down. It is not intended to section 7. The guide is also available to download at be a comprehensive record of all those who played a northdowntourism.com and visitstrangfordlough.co.uk Contents Montgomery A2 Estate boundaries McLellan Anderson approximate. Austin Dunlop Kyle Blackwood McDowell Kyle Kennedy Hamilton Wilson McMillin Hamilton Stevenson Murray Aicken A2 Belfast Road Adams Ross Pollock Hamilton Cunningham Nesbit Reynolds Stevenson Stennors Allen Harper Bayly Kennedy HAMILTON Hamilton WatsonBangor to A21 Boyd Montgomery Frazer Gibson Moore Cunningham -

Viscount Frankfort, Sir Charles Burton and County Carlow in the 1840S

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Norton, Desmond A. G. Working Paper Viscount Frankfort, Sir Charles Burton and county Carlow in the 1840s Centre for Economic Research Working Paper Series, No. WP01/20 Provided in Cooperation with: UCD School of Economics, University College Dublin (UCD) Suggested Citation: Norton, Desmond A. G. (2001) : Viscount Frankfort, Sir Charles Burton and county Carlow in the 1840s, Centre for Economic Research Working Paper Series, No. WP01/20, University College Dublin, Department of Economics, Dublin, http://hdl.handle.net/10197/1280 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/72434 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an -

Drawing Lines on Pages: Remaking the Catholic Parish Maps of Ireland As a Tidal Public Geography

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title Drawing lines on pages: remaking the Catholic parish maps of Ireland as a tidal public geography Author(s) O'Mahony, Eoin; Murphy, Michael J. Publication date 2017-11 Original citation O’Mahony, E. and Murphy, M. (2018) 'Drawing lines on pages: remaking the Catholic parish map of Ireland as a tidal public geography', Irish Geography, 51(1), doi: 10.2014/igj.v51i1.1326 Type of publication Article (peer-reviewed) Link to publisher's http://www.irishgeography.ie/index.php/irishgeography version http://dx.doi.org/10.2014/igj.v51i1.1326 Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Rights © 2018 the authors. Published by Geographical Society of Ireland under under Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/5733 from Downloaded on 2021-09-26T12:48:47Z IGIrish Geography NOVEMBER 2017 ISSN: 0075-0778 (Print) 1939-4055 (Online) http://www.irishgeography.ie Drawing lines on pages: remaking the Catholic parish maps of Ireland as a tidal public geography Eoin O’Mahony and Michael Murphy How to cite: O’Mahony, E. and Murphy, M. (2018) Drawing lines on pages: remaking the Catholic parish map of Ireland as a tidal public geography. Irish Geography, 51(1), XX–XX, DOI: 10.2014/igj. v51i1.1326 Irish Geography Vol. 51, No. 1 May 2018 DOI: 10.2014/igj.v51i1.1242 Drawing lines on pages: remaking the Catholic parish maps of Ireland as a tidal public geography *Eoin O’Mahony, UCD School of Geography, Newman Building, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland. -

Brian Friel and the Politics of the Anglo-Irish Language

Colby Quarterly Volume 26 Issue 4 December Article 7 December 1990 Brian Friel and the Politics of the Anglo-Irish Language F. C. McGrath Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 26, no.4, December 1990, p.241-248 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. McGrath: Brian Friel and the Politics of the Anglo-Irish Language Brian Friel and the Politics of the Anglo-Irish Language byF. C. McGRATH ANGUAGE has always been used as a political and social weapon. It has been L used to oppress a colonized or conquered people, and it has been used to police the borders ofsocial class. In Ireland it has been used in both these ways. After the British had consolidated their colonization of Ireland, Gaelic was outlawed, and its use stigmatized a class of people who were conquered, oppressed, and impoverished. B~fore independence in 1922 Irish-accented Eng lish' including degrees ofIrish accent, established social hierarchies-thecloser to British English, the higher the class. George Steiner's observation about upperclass British accents applied with particular force in Ireland: "Upper-class English diction, with its sharpened vowels, elisions, and modish slurs, is both a code for mutual recognition-accent is worn like a coat of arms-and an instrument of ironic exclusion" (32). Since the late nineteenth century, however, knowledge ofthe old Gaelic has been turned into an offensive political weapon and a badge of Irish nationalist affiliation; and today the status of the Anglo-Irish language, that is, English as spoken by the Irish, has become a major concern for Brian Friel and other Irish writers associated with his Field Day Theatre Group. -

Engineers Area Central Eng N-9-418 JCTN.OF N9 with LP1003 at TURN to VIA CLOGNA TD

Road Schedule 05 September 2012 Road ID Starting At Via Ending At Min. (Max.) Length Width Engineers Area Central Eng N-9-418 JCTN.OF N9 WITH LP1003 AT TURN TO VIA CLOGNA TD. JCTN. OF N9 WITH L-8185-0 IN CLOGNA 11.40 (11.40 1,421.00 MILFORD N-9-427 JCTN. OF N9 WITH L-8185-0 IN CLOGNA VIA MORTARSTOWN 11.40 (11.40 1,966.00 N-9-439 E.O.S.L. SOUTH OF HOTEL IN VIA MORTARSTOWN E.O.S.L. NORTH OF HOTEL IN 11.70 (11.70 606.00 MORTARSTOWN MORTARSTOWN N-9-443 E.O.S.L. NORTH OF HOTEL IN E.O.S.L. NORTH OF MUNELLY`S 11.70 (11.70 1,242.00 MORTARSTOWN GARAGE N-9-450 E.O.S.L. NORTH OF MUNELLY`S VIA CARLOW TOWN JCTN. OF N9 WITH TULLOW ST IN 9.00 (9.00) 1,493.00 GARAGE SHAMROCK SQUARE N-9-459 JCTN. OF N9 WITH TULLOW ST IN VIA CARLOW TOWN E.O.S.L. NORTH OF LAPPLE/BRAUN 10.00 (10.00 1,914.00 SHAMROCK SQUARE ROUNDABOUT N-9-471 E.O.S.L. NORTH OF LAPPLE/BRAUN VIA POLLERTON JCTN. OF N9 WITH PALATINE ROAD 11.00 (11.00 2,149.00 ROUNDABOUT IN BALLYVERGAL N-9-485 JCTN. OF N9 WITH PALATINE ROAD COUNTY KILDARE BOUNDS IN 10.00 (10.00 386.00 IN BALLYVERGAL BALLYVERGAL N-9-496 KILDARE BOUNDS AT KILDARE BOUNDS AT 10.00 (10.00 384.00 KNOCKNAGEE\GORTEENGRONE GORTEENGRONE\BALLAGHMOON BOUNDARY BOUNDARY N-80-254 ENGERNING AREA BOUNDARY 1&2 JUNCTION OF N80 WITH L-1023-0 0.00 (0.00) 427.00 N-80-255 JUNCTION OF N80 WITH L-1023-0 JUNCTION OF L-1026-0 WITH R-725-0 11.00 (11.00 2,792.00 EAST OF WALLS FORGE N-80-272 JUNCTION OF L-1026-0 WITH R-725-0 VIA CARLOW TOWN TULLOW RD ROUNDABOUT 10.40 (10.40 1,184.00 EAST OF WALLS FORGE N-80-293 TULLOW RD ROUNDABOUT O BRIEN RD JCTN. -

Your Donegal Family

YOUR DONEGAL FAMILY A GUIDE TO GENEALOGY SOURCES CULTURE DIVISION, DONEGAL COUNTY COUNCIL Donegal County Museum Collection The information contained in this publication was correct at the time of going to print. May 2020 A GUIDE TO TRACING YOUR DONEGAL ANCESTORS | 3 Genealogy is the study of one’s ancestors or family history and is one of the most popular hobbies in the world. Genealogy makes history come alive because when people learn about their ancestors, they are able to make connections to historical events. Family History is the biographical research into your ancestors. The aim is typically to produce a well-documented narrative history, of interest to family members and perhaps future generations. It involves putting flesh on the skeleton of what is produced by genealogy and involves the study of the historical circumstances and geographical situation in which ancestors lived. As custodians of the collective memory of County Donegal, genealogy/ family history resources are an important Culture Division service. This booklet was produced by the Library, Archives and Museum Services of the Culture Division, Donegal County Council to provide a brief introduction to resources available within these services and to other resources and agencies that can help to guide researchers in tracing their Donegal family tree. While Donegal County Library, Donegal County Archives and the Donegal County Museum are happy to provide guidance and assistance, they are not genealogical institutions and in general they cannot conduct detailed research for individuals. A GUIDE TO TRACING YOUR DONEGAL ANCESTORS | 3 Beginning your Research o begin, try to establish as accurately and completely as possible the basic Tgenealogical facts of as many of your near relatives as you can: .