Drawing Lines on Pages: Remaking the Catholic Parish Maps of Ireland As a Tidal Public Geography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ballinleenty Townland, Co. Tipperary

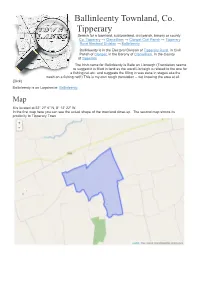

Ballinleenty Townland, Co. Tipperary Search for a townland, subtownland, civil parish, barony or countySearch Co. Tipperary → Clanwilliam → Clonpet Civil Parish → Tipperary Rural Electoral Division → Ballinleenty Ballinleenty is in the Electoral Division of Tipperary Rural, in Civil Parish of Clonpet, in the Barony of Clanwilliam, in the County of Tipperary The Irish name for Ballinleenty is Baile an Líontaigh (Translation seems to suggest it is filled in land as the word Líontaigh is related to the one for a fishing net etc. and suggests the filling in was done in stages aka the mesh on a fishing net!!) This is my own rough translation – not knowing the area at all. (Dick) Ballinleenty is on Logainm.ie: Ballinleenty. Map It is located at 52° 27' 6" N, 8° 12' 22" W. In the first map here you can see the actual shape of the townland close-up. The second map shows its proximity to Tipperary Town Leaflet | Map data © OpenStreetMap contributors Area Ballinleenty has an area of: 1,513,049 m² / 151.30 hectares / 1.5130 km² 0.58 square miles 373.88 acres / 373 acres, 3 roods, 21 perches Nationwide, it is the 17764th largest townland that we know about Within Co. Tipperary, it is the 933rd largest townland Borders Ballinleenty borders the following other townlands: Ardavullane to the west Ardloman to the south Ballynahow to the west Breansha Beg to the east Clonpet to the east Gortagowlane to the north Killea to the south Lackantedane to the east Rathkea to the west Subtownlands We don't know about any subtownlands in Ballinleenty. -

Appendix A16.8 Townland Boundaries to Be Crossed by the Proposed Project

Environmental Impact Assessment Report: Volume 3 Part B of 6 Appendix A16.8 Townland Boundaries to be Crossed by the Proposed Project TB No.: 1 Townlands: Abbotstown/ Dunsink Parish: Castleknock Barony: Castleknock NGR: 309268, 238784 Description: This townland boundary is marked at the same location on all the OS map editions. It is formed by a road, which today have been truncated by the M50 to the south-east. The tarmac surface of the road is still present at this location, although overgrown. The road also separated the demesne associated with Abbotstown House and Hillbrook (DL 1, DL 2). Reference: OS mapping, field inspection TB No.: 2 Townlands: Dunsink/ Sheephill Parish: Castleknock Barony: Castleknock NGR: 309327, 238835 Description: This townland boundary is marked at the same location on all the OS map editions. It is formed by a road, which today have been truncated by the M50 to the south-east. The tarmac surface of the road is still present at this location, although overgrown. The road also separated the demesne associated with Abbotstown House (within the townland of Sheephill) and Hillbrook (DL 1, DL 2). The remains of a stone demesne wall associated with Abbotstown are located along the northern side of the road (UBH 2). Reference: OS mapping, field inspection 32102902/EIAR/3B Environmental Impact Assessment Report: Volume 3 Part B of 6 TB No.: 3 Townlands: Sheephill/ Dunsink Parish: Castleknock Barony: Castleknock NGR: 310153, 239339 Description: This townland boundary is marked at the same location on all the OS map editions. It is formed by a road, which today have been truncated by the M50 to the south. -

Reforming Local Government in Early Twentieth Century Ireland

Creating Citizens from Colonial Subjects: Reforming Local Government in Early Twentieth Century Ireland Dr. Arlene Crampsie School of Geography, Planning and Environmental Policy University College Dublin ABSTRACT: Despite the incorporation of Ireland as a constituent component of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland through the 1801 Act of Union, for much of the early part of the nineteenth century, British policy towards Ireland retained its colonial overtones. However, from the late 1860s a subtle shift began to occur as successive British governments attempted to pacify Irish claims for independence and transform the Irish population into active, peaceful, participating British citizens. This paper examines the role played by the Local Government (Ireland) Act of 1898 in affecting this transformation. The reform of local government enshrined in the act not only offered the Irish population a measure of democratic, representative, local self- government in the form of county, urban district, and rural district councils, but also brought Irish local government onto a par with that of the rest of the United Kingdom. Through the use of local and national archival sources, this paper seeks to illuminate a crucial period in Anglo-Irish colonial relations, when for a number of years, the Irish population at a local level, at least, were treated as equal imperial citizens who engaged with the state and actively operated as its locally based agents. “Increasingly in the nineteenth century the tentacles of the British Empire were stretching deep into the remote corners of the Irish countryside, bearing with them schools, barracks, dispensaries, post offices, and all the other paraphernalia of the … state.”1 Introduction he Act of Union of 1801 moved Ireland from the colonial periphery to the metropolitan core, incorporating the island as a constituent part of the imperial power of the United TKingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. -

![County Londonderry - Official Townlands: Administrative Divisions [Sorted by Townland]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6319/county-londonderry-official-townlands-administrative-divisions-sorted-by-townland-216319.webp)

County Londonderry - Official Townlands: Administrative Divisions [Sorted by Townland]

County Londonderry - Official Townlands: Administrative Divisions [Sorted by Townland] Record O.S. Sheet Townland Civil Parish Barony Poor Law Union/ Dispensary /Local District Electoral Division [DED] 1911 D.E.D after c.1921 No. No. Superintendent Registrar's District Registrar's District 1 11, 18 Aghadowey Aghadowey Coleraine Coleraine Aghadowey Aghadowey Aghadowey 2 42 Aghagaskin Magherafelt Loughinsholin Magherafelt Magherafelt Magherafelt Aghagaskin 3 17 Aghansillagh Balteagh Keenaght Limavady Limavady Lislane Lislane 4 22, 23, 28, 29 Alla Lower Cumber Upper Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Claudy Claudy 5 22, 28 Alla Upper Cumber Upper Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Claudy Claudy 6 28, 29 Altaghoney Cumber Upper Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Ballymullins Ballymullins 7 17, 18 Altduff Errigal Coleraine Coleraine Garvagh Glenkeen Glenkeen 8 6 Altibrian Formoyle / Dunboe Coleraine Coleraine Articlave Downhill Downhill 9 6 Altikeeragh Dunboe Coleraine Coleraine Articlave Downhill Downhill 10 29, 30 Altinure Lower Learmount / Banagher Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Banagher Banagher 11 29, 30 Altinure Upper Learmount / Banagher Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Banagher Banagher 12 20 Altnagelvin Clondermot Tirkeeran Londonderry Waterside Rural [Glendermot Waterside Waterside until 1899] 13 41 Annagh and Moneysterlin Desertmartin Loughinsholin Magherafelt Magherafelt Desertmartin Desertmartin 14 42 Annaghmore Magherafelt Loughinsholin Magherafelt Bellaghy Castledawson Castledawson 15 48 Annahavil Arboe Loughinsholin Magherafelt Moneymore Moneyhaw -

Mailing Address Is 1931 W. Glenoaks Blvd., Glendale. CA 91201 Vol.83 Sunday 14Th May

The Irish Center of Southern California Inc., is a 503 c (3) Not for Profit Corporation. Our tax ID is 95-4442397. We are a fundraising group with no “paid” staff. Our primary aim is to acquire a multi- purpose facility including a theater, library, social hall, meeting rooms etc. If you have “any news” re graduations, births, weddings, deaths, relocating etc. please send to: [email protected]. Our address is 1931 W. Glenoaks Blvd., Glendale. CA 91201. If you know anyone who would like to receive this newsletter and doesn’t have a computer we will send by post. Let us know. This goes to over 2800 email addresses. We would like to thank those people who donated to the Irish Center to help us with expenses (including ink and postage for this newsletter: Kathleen Riordan Kiel, Redondo Beach; Dr & Mrs Catherine Thyen, Corona Del Mar; Irish American Bar Association, Los Angeles; Margaret C. Hennessy, La Verne; Denise Nolan Delurgio, Redondo Beach; Brenda O. Welsh, Los An- geles; Joseph P. & Linnea V. Praml, West Hollywood; Terry N. McConville, Mission Hills; Richard & Myra A. Butler Hubacher, Los Angeles. I have been involved with the Irish Community in Los Angeles since about 1970. First with the Shamrock Show, then with the Irish Hour and followed by the Irish Center. I have en- joyed the ride. I have made so many good friends. I had wonderful support. This will be my last newsletter. I was 86 on the 28th March. I didn’t feel very well around that time. I ended up in hospital with pneumonia. -

Commodore John Barry

Commodore John Barry Day, 13th September Commodore John Barry (1745-1803) a native of County Wexford, Ireland was a Continental Navy hero of the American War for Independence. Barry’s many victories at sea during the Revolution were important to the morale of the Patriots as well as to the successful prosecution of the War. When the First Congress, acting under the new Constitution of the United States, authorized the raising and construction of the United States Navy, President George Washington turned to Barry to build and lead the nation’s new US Navy, the successor to the Continental Navy. On 22 February 1797, President Washington conferred upon Barry, with the advice and consent of the Senate, the rank of Captain with “Commission No. 1,” United States Navy, effective 7 June 1794. Barry supervised the construction of his own flagship, the USS UNITED STATES. As commander of the first United States naval squadron under the Constitution, which included the USS CONSTITUTION (“Old Ironsides”), Barry was a Commodore with the right to fly a broad pennant, which made him a flag officer. Commodore John Barry By Gilbert Stuart (1801) John Barry served as the senior officer of the United States Navy, with the title of “Commodore” (in official correspondence) under Presidents George Washington, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. The ships built by Barry, and the captains selected, as well as the officers trained, by him, constituted the United States Navy that performed outstanding service in the “Quasi-War” with France, in battles with the Barbary Pirates and in America’s Second War for Independence (the War of 1812). -

THE 1866 FENIAN RAID on CANADA WEST: a Study Of

` THE 1866 FENIAN RAID ON CANADA WEST: A Study of Colonial Perceptions and Reactions Towards the Fenians in the Confederation Era by Anthony Tyler D’Angelo A thesis submitted to the Department of History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada September, 2009 Copyright © Anthony Tyler D’Angelo, 2009 Abstract This thesis examines Canada West’s colonial perceptions and reactions towards the Fenian Brotherhood in the Confederation era. Its focus is on the impact of the Fenians on the contemporary public mind, beginning in the fall of 1864 and culminating with the Fenian Raid on the Niagara frontier in June 1866. Newspapers, sermons, first-hand accounts, and popular poems and books from the time suggest the Fenians had a significant impact on the public mind by nurturing and reflecting the province’s social and defensive concerns, and the Raid on Canada West was used by contemporaries after the fact to promote Confederation and support a young Canadian identity. ii Writing a thesis is sometimes fun, often frustrating and always exacting, but its completion brings a satisfaction like no other. I am grateful to Queen’s University and the Department of History for giving me the opportunity to pursue this study; its completion took far longer than I thought, but the lessons learned were invaluable. I am forever indebted to Dr. Jane Errington, whose patience, knowledge, guidance and critiques were as integral to this thesis as the words on the pages and the sources in the bibliography. I cannot imagine steering the murky waters of historiography and historical interpretation without her help. -

Ulster-Scots

Ulster-Scots Biographies 2 Contents 1 Introduction The ‘founding fathers’ of the Ulster-Scots Sir Hugh Montgomery (1560-1636) 2 Sir James Hamilton (1559-1644) Major landowning families The Colvilles 3 The Stewarts The Blackwoods The Montgomerys Lady Elizabeth Montgomery 4 Hugh Montgomery, 2nd Viscount Sir James Montgomery of Rosemount Lady Jean Alexander/Montgomery William Montgomery of Rosemount Notable individuals and families Patrick Montgomery 5 The Shaws The Coopers James Traill David Boyd The Ross family Bishops and ministers Robert Blair 6 Robert Cunningham Robert Echlin James Hamilton Henry Leslie John Livingstone David McGill John MacLellan 7 Researching your Ulster-Scots roots www.northdowntourism.com www.visitstrangfordlough.co.uk This publication sets out biographies of some of the part. Anyone interested in researching their roots in 3 most prominent individuals in the early Ulster-Scots the region may refer to the short guide included at story of the Ards and north Down. It is not intended to section 7. The guide is also available to download at be a comprehensive record of all those who played a northdowntourism.com and visitstrangfordlough.co.uk Contents Montgomery A2 Estate boundaries McLellan Anderson approximate. Austin Dunlop Kyle Blackwood McDowell Kyle Kennedy Hamilton Wilson McMillin Hamilton Stevenson Murray Aicken A2 Belfast Road Adams Ross Pollock Hamilton Cunningham Nesbit Reynolds Stevenson Stennors Allen Harper Bayly Kennedy HAMILTON Hamilton WatsonBangor to A21 Boyd Montgomery Frazer Gibson Moore Cunningham -

The Government's Executions Policy During the Irish Civil

THE GOVERNMENT’S EXECUTIONS POLICY DURING THE IRISH CIVIL WAR 1922 – 1923 by Breen Timothy Murphy, B.A. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D. DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH HEAD OF DEPARTMENT: Professor Marian Lyons Supervisor of Research: Dr. Ian Speller October 2010 i DEDICATION To my Grandparents, John and Teresa Blake. ii CONTENTS Page No. Title page i Dedication ii Contents iii Acknowledgements iv List of Abbreviations vi Introduction 1 Chapter 1: The ‗greatest calamity that could befall a country‘ 23 Chapter 2: Emergency Powers: The 1922 Public Safety Resolution 62 Chapter 3: A ‗Damned Englishman‘: The execution of Erskine Childers 95 Chapter 4: ‗Terror Meets Terror‘: Assassination and Executions 126 Chapter 5: ‗executions in every County‘: The decentralisation of public safety 163 Chapter 6: ‗The serious situation which the Executions have created‘ 202 Chapter 7: ‗Extraordinary Graveyard Scenes‘: The 1924 reinterments 244 Conclusion 278 Appendices 299 Bibliography 323 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to extend my most sincere thanks to many people who provided much needed encouragement during the writing of this thesis, and to those who helped me in my research and in the preparation of this study. In particular, I am indebted to my supervisor Dr. Ian Speller who guided me and made many welcome suggestions which led to a better presentation and a more disciplined approach. I would also like to offer my appreciation to Professor R. V. Comerford, former Head of the History Department at NUI Maynooth, for providing essential advice and direction. Furthermore, I would like to thank Professor Colm Lennon, Professor Jacqueline Hill and Professor Marian Lyons, Head of the History Department at NUI Maynooth, for offering their time and help. -

Viscount Frankfort, Sir Charles Burton and County Carlow in the 1840S

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Norton, Desmond A. G. Working Paper Viscount Frankfort, Sir Charles Burton and county Carlow in the 1840s Centre for Economic Research Working Paper Series, No. WP01/20 Provided in Cooperation with: UCD School of Economics, University College Dublin (UCD) Suggested Citation: Norton, Desmond A. G. (2001) : Viscount Frankfort, Sir Charles Burton and county Carlow in the 1840s, Centre for Economic Research Working Paper Series, No. WP01/20, University College Dublin, Department of Economics, Dublin, http://hdl.handle.net/10197/1280 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/72434 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an -

Donegal GAA County Convention 2020

Comhdáil Blaintuil 2020 CLG Dhún Na nGall Donegal GAA County Convention 2020 Choiste Dhún na nGall CLG Comdháil Bhliantúil CLG Dhún nan Gall 2020 Clár an Leabhair 1. Glacadh le Buan-Orduithe 2 2. Miontuairiscí Chomhdháil Bhliantúil CLG Dhún na nGall 3 3. Tuarascáil an Rúnaí 2020 12 4. Tuarascáil an Chisteora & an Iniúchóra ar chuntaisí an Choiste Condae don bhliain dár críoch 31ú Meán Fómhair 2020 5. Tuarascáil Oifigeach Chultúrtha agus Teanga 2020 23 6. Tuarascail Runaí Coiste Cheannais na gComórtaisí 28 7. Tuarascáil an Oifigeach Chaidrimh Phoiblí 2020 32 8. Óráid an Chathaoirligh 9. Toghadh na nOifigeach don bhlain 2021 43 10. Tuarascail Oifigeach Forbartha 44 11. Tuarascáil Choiste Iománaíochta 50 12. Tuarascáil Oifigeach Oiliúna 52 13. Tuarascáil Choiste na Réiteoirí 57 14. Tuarascáil Rúnaí Choiste na hIar Bhunscoileanna 60 15. Tuarascáil Rúnaí Chumann na mBunscoil 62 16. Tuarscail Thoscaire Ard Chomhairle 68 17. Tuarascail Rúnaí an Choiste Éisteachta 70 18. Tuarscáil Comhairle Uladh (1) 71 19 Tuarscáil Comhairle Uladh (2) 72 20. Tuarscáil Leas-Chathaoirleach 74 21 Tuarscáil Leas-Chisteoir 75 22. Tuarascáil Choiste Folláine agus Sláinte 76 22. Tuarascáil Choiste Pleanáil Cluichí 80 23. Ballraíocht 82 1 Buan-orduithe don Chomhdhail Bhliantuil Standing Orders for Annual Convention 1. The proposer of a resolution or an amendment shall formally propose the resolution or amendment. 2. A resolution or amendment shall require a formal seconder in order to establish a live debate. 3. The proposer of a resolution or an amendment may speak for five minutes but not more than five minutes. 4. A delegate speaking to a resolution or an amendment must not exceed three minutes. -

Michael Murphy and Jan Smaczny (Eds), Music in Nineteenth-Century Ireland

Michael Murphy and Jan Smaczny (eds), Music in Nineteenth-Century Ireland MICHAEL MURPHY AND JAN SMACZNY (EDS.), MUSIC IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY IRELAND (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2007), ISBN 978-1-84682-024-3, 336pp, €55 Let me start by declaring my colours. I come to this volume as a scholar of British music history, and one who has been occasionally puzzled by the lukewarm interest shown by musicologists in the relationships between Irish and British musical affairs in the Victorian period, despite the immediacy of cultural matters relating to Ireland (particularly Dublin) and its people in just about any London newspaper of the time, and the historical reality of a United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland after the Act of Union of 1800. This blind spot appears particularly to affect specialists in British musical life, especially those from British backgrounds (some perhaps carrying pre- conceptions about the shape and identity of Britain and Ireland that have been forged in more recent times), Stanford biographers and a few others excepted. Our Irish counterparts, and probably most of the readers of this journal, on the other hand, seem far more willing to reach out and make connections, as has been demonstrated by the growing presence of speakers on Irish topics at the biennial Music in Nineteenth- Century Britain conference—usually scholars hailing from or working in Ireland. The roll-call of authors in Michael Murphy’s and Jan Smaczny’s edited volume of fifteen essays on music in nineteenth-century Ireland bears out these observations, with all bar one, to my knowledge, having strong connections with Ireland, and a few teasing out relationships between the two cultures in their contributions.