THE 1866 FENIAN RAID on CANADA WEST: a Study Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victoria County Centennial History F 5498 ,V5 K5

Victoria County Centennial History F 5498 ,V5 K5 31o4 0464501 »» By WATSON KIRKCONNELL, M. A. PRICE $2.00 0U-G^5O/ Date Due SE Victoria County Centennial History i^'-'^r^.J^^, By WATSON KIRKCONNELL, M. A, WATCHMAN-WARDER PRESS LINDSAY, 1921 5 Copyrighted in Canada, 1921, By WATSON KIRKCONNELL. 0f mg brnttf^r Halter mtfa fell in artton in ttje Sattte nf Amiena Angnfit 3, ISiB, tlfia bnok ia aflfertinnatelg in^^iratei. AUTHOR'S PREFACE This history has been appearing serially through the Lindsaj "Watchman-Warder" for the past eleven months and is now issued in book form for the first time. The occasion for its preparation is, of course, the one hundredth anniversary of the opening up of Victoria county. Its chief purposes are four in number: — (1) to place on record the local details of pioneer life that are fast passing into oblivion; (2) to instruct the present generation of school-children in the ori- gins and development of the social system in which they live; (3) to show that the form which our county's development has taken has been largely determined by physiographical, racial, social, and economic forces; and (4) to demonstrate how we may, after a scien- tific study of these forces, plan for the evolution of a higher eco- nomic and social order. The difficulties of the work have been prodigious. A Victoria County Historical Society, formed twenty years ago for a similar purpose, found the field so sterile that it disbanded, leaving no re- cords behind. Under such circumstances, I have had to dig deep. -

Hheritage Gazette of the Trent Valley, Vol. 20, No. 2 August 2015Eritage

ISSN 1206-4394 herITage gazeTTe of The TreNT Valley Volume 21, Number 2, august 2016 Table of Contents President’s Corner ………………….……………………………………..………………...…… Rick Meridew 2 Italian Immigration to Peterborough: the overview ……………………………………………. Elwood H. Jones 3 Appendix: A Immigration trends to North America, 4; B Immigration Statistics to USA, 5; C Immigration statistics from 1921 printed census, 6; D Using the personal census 1921, 6; E Using Street Directories 1925, 7 Italian-Canadians of Peterborough, Ontario: First wave 1880-1925 ……………………..………. Berenice Pepe 9 What’s in a Name: Stony or Stoney? …………………………………………………………. Elwood H. Jones 14 Queries …………………………………………………………..…………… Heather Aiton Landry and others 17 George Stenton and the Fenian Raid ………………………………………………….……… Stephen H. Smith 19 Building Boom of 1883 ……………………………………………………………………….. Elwood H. Jones 24 Postcards from Peterborough and the Kawarthas …………………………… …………………………………… 26 Discovering Harper Park: a walkabout in Peterborough’s urban green space ……………………… Dirk Verhulst 27 Pathway of Fame ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 28 Hazelbrae Barnardo Home Memorial 1921, 1922, and 1923 [final instalment] ……… John Sayers and Ivy Sucee 29 Thomas Ward fonds #584 …………………………………………..……………………. TVA Archives Report 33 J. J. Duffus, Car King, Mayor and Senator ………………………………………………………………………… 34 Senator Joseph Duffus Dies in City Hospital ………………………….…… Examiner, 7 February 1957 34 A plaque in honour of J. J. Duffus will be unveiled this fall …………………………………………….. 37 Special issue on Quaker Oats 115 Years in Peterborough: invitation for ideas ……………………………… Editor 37 Trent Valley Archives Honoured with Civic Award ………………………………………………………………… 42 Ladies of the Lake Cemetery Tour ………………………………………………………..………………………… 43 The Log of the “Dorothy” …………………………………………………….…………………….. F. H. Dobbin 39 Frank Montgomery Fonds #196 ………………………………………………….………… TVA Archives Report 40 District of Colborne founding document: original at Trent Valley Archives ……………………………………….. 41 Genealogical Resources at Trent Valley Archives ………………………………..……………. -

Making Fenians: the Transnational Constitutive Rhetoric of Revolutionary Irish Nationalism, 1858-1876

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE 8-2014 Making Fenians: The Transnational Constitutive Rhetoric of Revolutionary Irish Nationalism, 1858-1876 Timothy Richard Dougherty Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Modern Languages Commons, and the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dougherty, Timothy Richard, "Making Fenians: The Transnational Constitutive Rhetoric of Revolutionary Irish Nationalism, 1858-1876" (2014). Dissertations - ALL. 143. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/143 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT This dissertation traces the constitutive rhetorical strategies of revolutionary Irish nationalists operating transnationally from 1858-1876. Collectively known as the Fenians, they consisted of the Irish Republican Brotherhood in the United Kingdom and the Fenian Brotherhood in North America. Conceptually grounded in the main schools of Burkean constitutive rhetoric, it examines public and private letters, speeches, Constitutions, Convention Proceedings, published propaganda, and newspaper arguments of the Fenian counterpublic. It argues two main points. First, the separate national constraints imposed by England and the United States necessitated discursive and non- discursive rhetorical responses in each locale that made -

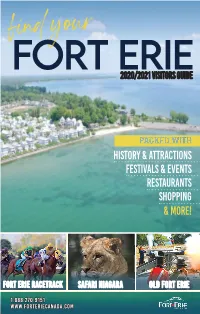

2020/2021 Visitors Guide

2020/2021 Visitors Guide packed with History & Attractions Festivals & Events Restaurants Shopping & more! fort erie Racetrack safari niagara old fort erie 1.888.270.9151 www.forteriecanada.com And Mayor’s Message They’re Off! Welcome to Fort Erie! We know that you will enjoy your stay with us, whether for a few hours or a few days. The members of Council and I are delighted that you have chosen to visit us - we believe that you will find the xperience more than rewarding. No matter your interest or passion, there is something for you in Fort Erie. 2020 Schedule We have a rich history, displayed in our historic sites and museums, that starts with our lndigenous peoples over 9,000 years ago and continues through European colonization and conflict and the migration of United Empire l yalists, escaping slaves and newcomers from around the world looking for a new life. Each of our communities is a reflection of that histo y. For those interested in rest, relaxation or leisure activities, Fort Erie has it all: incomparable beaches, recreational trails, sports facilities, a range of culinary delights, a wildlife safari, libraries, lndigenous events, fishin , boating, bird-watching, outdoor concerts, cycling, festivals throughout the year, historic battle re-enactments, farmers’ markets, nature walks, parks, and a variety of visual and performing arts events. We are particularly proud of our new parks at Bay Beach and Crystal Ridge. And there is a variety of places for you to stay while you are here. Fort Erie is the gateway to Canada from the United States. -

Wealth Mobility in the 1860S

Economics Working Papers 9-18-2020 Working Paper Number 20018 Wealth Mobility in the 1860s Brandon Dupont Western Washington University Joshua L. Rosenbloom Iowa State University, [email protected] Original Release Date: September 18, 2020 Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/econ_workingpapers Part of the Economic History Commons, Growth and Development Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, and the Regional Economics Commons Recommended Citation Dupont, Brandon and Rosenbloom, Joshua L., "Wealth Mobility in the 1860s" (2020). Economics Working Papers: Department of Economics, Iowa State University. 20018. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/econ_workingpapers/113 Iowa State University does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, age, ethnicity, religion, national origin, pregnancy, sexual orientation, gender identity, genetic information, sex, marital status, disability, or status as a U.S. veteran. Inquiries regarding non-discrimination policies may be directed to Office ofqual E Opportunity, 3350 Beardshear Hall, 515 Morrill Road, Ames, Iowa 50011, Tel. 515 294-7612, Hotline: 515-294-1222, email [email protected]. This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please visit lib.dr.iastate.edu. Wealth Mobility in the 1860s Abstract We offer new evidence on the regional dynamics of wealth holding in the United States over the Civil War decade based on a hand-linked random sample of wealth holders drawn from the 1860 census. Despite the wealth shock caused by emancipation, we find that patterns of wealth mobility were broadly similar for northern and southern residents in 1860. -

Report of the Department of Militia and Defence Canada for the Fiscal

The documents you are viewing were produced and/or compiled by the Department of National Defence for the purpose of providing Canadians with direct access to information about the programs and services offered by the Government of Canada. These documents are covered by the provisions of the Copyright Act, by Canadian laws, policies, regulations and international agreements. Such provisions serve to identify the information source and, in specific instances, to prohibit reproduction of materials without written permission. Les documents que vous consultez ont été produits ou rassemblés par le ministère de la Défense nationale pour fournir aux Canadiens et aux Canadiennes un accès direct à l'information sur les programmes et les services offerts par le gouvernement du Canada. Ces documents sont protégés par les dispositions de la Loi sur le droit d'auteur, ainsi que par celles de lois, de politiques et de règlements canadiens et d’accords internationaux. Ces dispositions permettent d'identifier la source de l'information et, dans certains cas, d'interdire la reproduction de documents sans permission écrite. u~ ~00 I"'.?../ 12 GEORGE V SESSIONAL PAPER No. 36 A. 1922 > t-i REPORT OF THE DEPARTMENT OF MILITIA AND DEFENCE CANADA FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDING MARCH 31 1921 PRINTED BY ORDER OF PARLIAMENT H.Q. 650-5-21 100-11-21 OTTAWA F. A. ACLAND PRINTER TO THE KING'S MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY 1921 [No. 36-1922] 12 GEORGE V SESSIONAL PAPER No. 36 A. 1922 To General His Excellency the Right HQnourable Lord Byng of Vimy, G.C.B., G.C.M.G., M.V.0., Governor General and Commander in Chief of the Dominion of Canada. -

Nineteenth-Century Serial Fictions in Transnational Perspective, 1830S-1860S

Popular Culture – Serial Culture: Nineteenth-Century Serial Fictions in Transnational Perspective, 1830s-1860s University of Siegen, April 28-30, 2016 Conveners: Prof. Dr. Daniel Stein / Lisanna Wiele, M.A. North American Literary and Cultural Studies Recent publications such as Transnationalism and American Serial Fiction (Okker 2011) and Serialization in Popular Culture (Allen/van den Berg 2014) remind us that serial modes of storytelling, publication, and reception have been among the driving forces of modern culture since the first half of the nineteenth century. Indeed, as studies of Victorian serial fiction, the French feuilleton novel, and American magazine fiction indicate, much of what we take for granted as central features of contemporary serial fictions traces back to a particular period in the nineteenth century between the 1830s and the 1860s. This is the time when new printing techniques allowed for the mass publication of affordable reading materials, when literary authorship became a viable profession, when reading for pleasure became a popular pastime for increasingly literate and socially diverse audiences, and when previously predominantly national print markets became thoroughly international. These transformations enabled, and, in turn, were enabled by, the emergence of popular serial genres, of which the so-called city mystery novels are a paradigmatic example. In the wake of the success of Eugène Sue’s Les Mystères de Paris (1842-43), a great number of these city mysteries appeared across Europe (especially France, Great Britain, and Germany) and the United States, adapting the narrative formulas and basic storylines of Sue’s roman feuilleton to different cultural, social, economic, and political contexts. -

The North-West Rebellion 1885 Riel on Trial

182-199 120820 11/1/04 2:57 PM Page 182 Chapter 13 The North-West Rebellion 1885 Riel on Trial It is the summer of 1885. The small courtroom The case against Riel is being heard by in Regina is jammed with reporters and curi- Judge Hugh Richardson and a jury of six ous spectators. Louis Riel is on trial. He is English-speaking men. The tiny courtroom is charged with treason for leading an armed sweltering in the heat of a prairie summer. For rebellion against the Queen and her Canadian days, Riel’s lawyers argue that he is insane government. If he is found guilty, the punish- and cannot tell right from wrong. Then it is ment could be death by hanging. Riel’s turn to speak. The photograph shows What has happened over the past 15 years Riel in the witness box telling his story. What to bring Louis Riel to this moment? This is the will he say in his own defence? Will the jury same Louis Riel who led the Red River decide he is innocent or guilty? All Canada is Resistance in 1869-70. This is the Riel who waiting to hear what the outcome of the trial was called the “Father of Manitoba.” He is will be! back in Canada. Reflecting/Predicting 1. Why do you think Louis Riel is back in Canada after fleeing to the United States following the Red River Resistance in 1870? 2. What do you think could have happened to bring Louis Riel to this trial? 3. -

Rural Dress in Southwestern Missouri Between 1860 and 1880 by Susan

Rural dress in southwestern Missouri between 1860 and 1880 by Susan E. McFarland Hooper A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Department: Textiles and Clothing Major: Textiles and Clothing Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1976 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 SOURCES OF COSTUME, INFORMATION 4 SOUTHWESTERN MISSOURI, 1860 THROUGH 1880 8 Location and Industry 8 The Civil War 13 Evolution of the Towns and Cities 14 Rural Life 16 DEVELOPMENT OF TEXTILES AND APPAREL INDUSTRIES BY 1880 19 Textiles Industries 19 Apparel Production 23 Distribution of Goods 28 TEXTILES AND CLOTHING AVAILABLE IN SOUTHWESTERN MISSOURI 31 Goods Available from 1860 to 1866 31 Goods Available after 1866 32 CLOTHING WORN IN RURAL SOUTHWESTERN MISSOURI 37 Clothing Worn between 1860 and 1866 37 Clothing Worn between 1866 and 1880 56 SUMMARY 64 REFERENCES 66 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 70 GLOSSARY 72 iii LIST OF TABLES Page Table 1. Selected services and businesses in operation in Neosho, Missouri, 1860 and 1880 15 iv LIST OF MAPS Page Map 1. State of Missouri 9 Map 2. Newton and Jasper Counties, 1880 10 v LIST OF PHOTOGRAPHS Page Photograph 1. Southwestern Missouri family group, c. 1870 40 Photograph 2. Detail, southwestern Missouri family group, c. 1870 41 Photograph 3. George and Jim Carver, taken in Neosho, Missouri, c. 1875 46 Photograph 4. George W. Carver, taken in Neosho, Missouri, c. 1875 47 Photograph 5. Front pieces of manls vest from steamship Bertrand, 1865 48 Photograph 6. -

Available to Download

A Desert Between Us & Them INTRODUCTION The activities and projects in this guide have been developed to compliment the themes of the A Desert Between Us & Them documentary series. These ideas are meant to be an inspiration for teachers and students to become engaged with the material, exercise their creative instincts, and empower their critical thinking. You will be able to adapt the activities and projects based on the grade level and readiness of your students. The International Society for Technology in Education (http://www.iste.org) sets out standards for students to “learn effectively and live productively in an increasingly global and digital world.” These standards, as described in the following pages, were used to develop the activities and projects in this guide. The Ontario Visual Heritage Project offers robust resources on the A Desert Between Us & Them website http://1812.visualheritage.ca. There is a link to additional A Desert Between Us & Them stories posted on our YouTube Channel, plus the new APP for the iPad, iPhone and iPod. A Desert Between Us & Them is one in a series of documentaries produced by the Ontario Visual Heritage Project about Ontario’s history. Find out more at www.visualheritage.ca. HOW TO NAVIGATE THIS GUIDE In this guide, you will find a complete transcript of each episode of A Desert Between Us & Them. The transcripts are broken down into chapters, which correspond with the chapters menus on the DVD. Notable details are highlighted in orange, which may dovetail with some of the projects and activities that you have already planned for your course unit. -

Bowl Round 3

IHBB Beta Bowl 2018-2019 Bowl Round 3 Bowl Round 3 First Quarter (1) Theodosius II used the help of fans who watched chariot racing in this city’s Hippodrome to build this city’s famous double walls. An engineer named Orban helped build a giant cannon that could fire 600 pound cannonballs against this city. That cannon was used in Mehmed II’s conquest of this city in 1453. For ten points, name this capital of the Byzantine Empire, which was later renamed Istanbul. ANSWER: Constantinople (do not accept Istanbul or Byzantium) (2) Zoroastrians protect this substance, called atar, in temples named for it. In 1861, Queen Victoria banned the practice of sati, whereby Hindu widows would kill themselves with this substance. This substance is personified by the Hindu god Agni. For ten points, name this substance which, in Greek myth, Prometheus stole from the gods and gave to humans. ANSWER: fire (3) A “Great” ruler with this name began the process of Christianizing the Kievan Rus. A modern leader with this first name alternated terms as president of his country with Dmitry Medvedev and succeeded Boris Yeltsin. For ten points, give this first name of the current President of Russia. ANSWER: Vladimir (accept Vladimir the Great; accept Vladimir Putin after “modern” is read) (4) One leader of this country promoted the Nasakom ideology and the five principles, or pancasila, and was overthrown in 1967 before a massive purge of Communists. That leader was succeeded by a former general who founded the New Order, Suharto. For ten points, name this Asian archipelagic country once led by Sukarno and has its capital at Jakarta. -

Ontario: the Centre of Confederation?

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2018-10 Reconsidering Confederation: Canada's Founding Debates, 1864-1999 University of Calgary Press Heidt, D. (Ed.). (2018). "Reconsidering Confederation: Canada's Founding Debates, 1864-1999". Calgary, AB: University of Calgary Press. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/108896 book https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca RECONSIDERING CONFEDERATION: Canada’s Founding Debates, 1864–1999 Edited by Daniel Heidt ISBN 978-1-77385-016-0 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence.