Brian Friel and the Politics of the Anglo-Irish Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ballinleenty Townland, Co. Tipperary

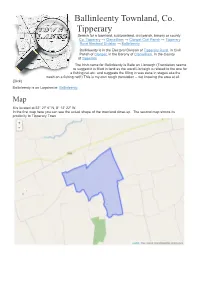

Ballinleenty Townland, Co. Tipperary Search for a townland, subtownland, civil parish, barony or countySearch Co. Tipperary → Clanwilliam → Clonpet Civil Parish → Tipperary Rural Electoral Division → Ballinleenty Ballinleenty is in the Electoral Division of Tipperary Rural, in Civil Parish of Clonpet, in the Barony of Clanwilliam, in the County of Tipperary The Irish name for Ballinleenty is Baile an Líontaigh (Translation seems to suggest it is filled in land as the word Líontaigh is related to the one for a fishing net etc. and suggests the filling in was done in stages aka the mesh on a fishing net!!) This is my own rough translation – not knowing the area at all. (Dick) Ballinleenty is on Logainm.ie: Ballinleenty. Map It is located at 52° 27' 6" N, 8° 12' 22" W. In the first map here you can see the actual shape of the townland close-up. The second map shows its proximity to Tipperary Town Leaflet | Map data © OpenStreetMap contributors Area Ballinleenty has an area of: 1,513,049 m² / 151.30 hectares / 1.5130 km² 0.58 square miles 373.88 acres / 373 acres, 3 roods, 21 perches Nationwide, it is the 17764th largest townland that we know about Within Co. Tipperary, it is the 933rd largest townland Borders Ballinleenty borders the following other townlands: Ardavullane to the west Ardloman to the south Ballynahow to the west Breansha Beg to the east Clonpet to the east Gortagowlane to the north Killea to the south Lackantedane to the east Rathkea to the west Subtownlands We don't know about any subtownlands in Ballinleenty. -

Appendix A16.8 Townland Boundaries to Be Crossed by the Proposed Project

Environmental Impact Assessment Report: Volume 3 Part B of 6 Appendix A16.8 Townland Boundaries to be Crossed by the Proposed Project TB No.: 1 Townlands: Abbotstown/ Dunsink Parish: Castleknock Barony: Castleknock NGR: 309268, 238784 Description: This townland boundary is marked at the same location on all the OS map editions. It is formed by a road, which today have been truncated by the M50 to the south-east. The tarmac surface of the road is still present at this location, although overgrown. The road also separated the demesne associated with Abbotstown House and Hillbrook (DL 1, DL 2). Reference: OS mapping, field inspection TB No.: 2 Townlands: Dunsink/ Sheephill Parish: Castleknock Barony: Castleknock NGR: 309327, 238835 Description: This townland boundary is marked at the same location on all the OS map editions. It is formed by a road, which today have been truncated by the M50 to the south-east. The tarmac surface of the road is still present at this location, although overgrown. The road also separated the demesne associated with Abbotstown House (within the townland of Sheephill) and Hillbrook (DL 1, DL 2). The remains of a stone demesne wall associated with Abbotstown are located along the northern side of the road (UBH 2). Reference: OS mapping, field inspection 32102902/EIAR/3B Environmental Impact Assessment Report: Volume 3 Part B of 6 TB No.: 3 Townlands: Sheephill/ Dunsink Parish: Castleknock Barony: Castleknock NGR: 310153, 239339 Description: This townland boundary is marked at the same location on all the OS map editions. It is formed by a road, which today have been truncated by the M50 to the south. -

![County Londonderry - Official Townlands: Administrative Divisions [Sorted by Townland]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6319/county-londonderry-official-townlands-administrative-divisions-sorted-by-townland-216319.webp)

County Londonderry - Official Townlands: Administrative Divisions [Sorted by Townland]

County Londonderry - Official Townlands: Administrative Divisions [Sorted by Townland] Record O.S. Sheet Townland Civil Parish Barony Poor Law Union/ Dispensary /Local District Electoral Division [DED] 1911 D.E.D after c.1921 No. No. Superintendent Registrar's District Registrar's District 1 11, 18 Aghadowey Aghadowey Coleraine Coleraine Aghadowey Aghadowey Aghadowey 2 42 Aghagaskin Magherafelt Loughinsholin Magherafelt Magherafelt Magherafelt Aghagaskin 3 17 Aghansillagh Balteagh Keenaght Limavady Limavady Lislane Lislane 4 22, 23, 28, 29 Alla Lower Cumber Upper Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Claudy Claudy 5 22, 28 Alla Upper Cumber Upper Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Claudy Claudy 6 28, 29 Altaghoney Cumber Upper Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Ballymullins Ballymullins 7 17, 18 Altduff Errigal Coleraine Coleraine Garvagh Glenkeen Glenkeen 8 6 Altibrian Formoyle / Dunboe Coleraine Coleraine Articlave Downhill Downhill 9 6 Altikeeragh Dunboe Coleraine Coleraine Articlave Downhill Downhill 10 29, 30 Altinure Lower Learmount / Banagher Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Banagher Banagher 11 29, 30 Altinure Upper Learmount / Banagher Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Banagher Banagher 12 20 Altnagelvin Clondermot Tirkeeran Londonderry Waterside Rural [Glendermot Waterside Waterside until 1899] 13 41 Annagh and Moneysterlin Desertmartin Loughinsholin Magherafelt Magherafelt Desertmartin Desertmartin 14 42 Annaghmore Magherafelt Loughinsholin Magherafelt Bellaghy Castledawson Castledawson 15 48 Annahavil Arboe Loughinsholin Magherafelt Moneymore Moneyhaw -

Developing Quality Cost Effective Interpreting and Translating Services

Developing Quality Cost Effective Interpreting & Translating Services FOR GOVERNMENT SERVICE PROVIDERS IN IRELAND National Consultative Committee on Racism and Interculturalism (NCCRI) i ii FOREWORD Over the past few years, the NCCRI has been involved in working with Government bodies to improve services to members of minority ethnic groups. This work has ranged from involvement in drafting the National Action Plan Against Racism (2005–2008) (NPAR) and in contributing to intercultural strategies arising from commitments in the NPAR, such as the Health Services Executive’s National Intercultural Health Strategy 2007–2012; to managing cross-border research on improving services to minority ethnic groups in Ireland, Scotland and Northern Ireland.1 Throughout this work, a recurring theme has been the need for professional, accurate, high quality interpreting and translating services for people with low proficiency in English; this was confirmed in the NCCRI Advocacy Paper2 Interpreting, Translation and Public Bodies in Ireland: The Need for Policy and Training in 2007. Many migrants to Ireland speak some English or attend English language classes; however, this does not necessarily mean they have sufficient English to interact effectively with Government bodies; this is particularly true in stressful and critical situations, for example in a health care or justice setting. The increasing diversity in languages spoken in Ireland today means that provision of interpreting and translating has become a pressing need if people with low proficiency in English are to experience equality of access and outcomes in their interaction with key Government services such as health, justice, education and housing. Recognising that there had been little research on the need for, and experiences of, interpreting and translation services in Ireland to date, the NCCRI approached the Office of the Minister for Integration seeking support for the current study. -

Volume 1 TOGHCHÁIN ÁITIÚLA, 1999 LOCAL ELECTIONS, 1999

TOGHCHÁIN ÁITIÚLA, 1999 LOCAL ELECTIONS, 1999 Volume 1 TOGHCHÁIN ÁITIÚLA, 1999 LOCAL ELECTIONS, 1999 Volume 1 DUBLIN PUBLISHED BY THE STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased through any bookseller, or directly from the GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS SALE OFFICE, SUN ALLIANCE HOUSE, MOLESWORTH STREET, DUBLIN 2 £12.00 €15.24 © Copyright Government of Ireland 2000 ISBN 0-7076-6434-9 P. 33331/E Gr. 30-01 7/00 3,000 Brunswick Press Ltd. ii CLÁR CONTENTS Page Foreword........................................................................................................................................................................ v Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................... vii LOCAL AUTHORITIES County Councils Carlow...................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Cavan....................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Clare ........................................................................................................................................................................ 12 Cork (Northern Division) .......................................................................................................................................... 19 Cork (Southern Division)......................................................................................................................................... -

Galway Campus

POSTGDUATE PROSPECTUS 2019 YOU START THE NEXT CHAPTER TOP % of Universities1 worldwide based on data from QS NUI Galway Campus Áras de Brún (School of Mathematics, Statistics and Applied Mathematics) Áras Uí Chathail/Student Information Desk (SID) Áras na Gaeilge The Quadrangle Áras na Mac Léinn and Bailey Allen Hall University Hospital Galway Lambe Institute for Translational Research and HRB Clinical Research Facility Centre for Adult Learning and Professional Development Huston School of Film and Digital Media Martin Ryan Building (Environmental, Marine and Energy Research) O’Donoghue Centre for Drama, Theatre and Performance Human Biology Building Biomedical Sciences Hardiman Library and Hardiman Research Building Lifecourse Building Arts Millennium Building Corrib Village (Student Residences) School of Psychology Engineering Building J.E. Cairnes School of Business & Economics Áras Moyola (School of Nursing and Midwifery; School of Health Sciences) Research and Innovation Centre Sports Centre Postgraduate Prospectus 2019 Prospectus Postgraduate IT Building Arts/Science Building NUI Galway NUI Galway Orbsen Building (NCBES and REMEDI) 01 Why Choose NUI Galway? of UNIVERSITIES WORLDWIDE according 92% to the QS World University of POSTGRADUATES are in employment Rankings 2018 or additional education or research within six months of graduating OVER YEARS of Home to INSIGHT innovative teaching and National Centre research excellence for Data Analytics SPINOUT COMPANIES €65.5m 16 in five years in RESEARCH funding in 2017 OF ALL STENTS -

Translations: a Movement Towards Reconciliation

Translations: a Movement Towards Reconciliation Michelle Andressa Alvarenga de Souza Abstract: This article proposes a postcolonial reading of Brian Friel’s Translations, understanding it as piece of work that presents a way out for Ireland to reconcile with England, its colonizer. It has taken the major theoreticians in postcolonial studies as premise to read the play as a place of hybridity. Keywords: Brian Friel; Translations; hybridity. Brian Friel was part of a group of six Northern artists1 who responded to the unsettled political situation in the country after the partition of Ireland in two states. This group was the Field Day Theatre Company, which set out “to contribute to the solution of the present crisis by producing analyses of the established opinions, myths and stereotypes which had become both a symptom and a cause of the current situation.”2 Their most significant proposition was the idea of an Irish “fifth province,” one that would be added to the four geographical provinces of Ireland (Connacht, Leinster, Munster and Ulster). This “fifth province” would not be a physical place, but would be a province of the mind: one capable of transcending the oppositions of Irish politics, a place where all conflicts are resolved. In order to constitute such a location each person is required to discover it for himself and within himself. According to Friel the fifth province is “a place for dissenters, traitors to the prevailing mythologies in the other four provinces” “through which we hope to devise another way of looking at Ireland, or another possible Ireland” (qtd. in Gray 7). -

The Irish Language, the English Army, and the Violence of Translation in Brian Friel's Translations

Colby Quarterly Volume 28 Issue 3 September Article 7 September 1992 Words Between Worlds: The Irish Language, the English Army, and the Violence of Translation in Brian Friel's Translations Collin Meissner Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 28, no.3, September 1992, p.164-174 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Meissner: Words Between Worlds: The Irish Language, the English Army, and t Words Between Worlds: The Irish Language, the English Army, and the Violence of Translation in Brian Friel's Translations 1 by COLLIN MEISSNER Ifpoetry were to be extinguished, my people, Ifwe were without history and ancient lays Forever. Everyone will pass unheralded. Giolla Brighde Mac Con Mighde2 Sirrah, your Tongue betrays your Guilt. You are an Irishman, and that is always sufficient Evidence with me. Justice Jonathan Thrasher, Fielding's Amelia3 etus begin by acknowledging that language is often employed as a political, L military, and economic resource in cultural, particularly colonial, encoun ters. Call it a weapon. Henry VIII's 1536 Act of Union decree is as good an example as any: "Be it enacted by auctoritie aforesaid that all Justices Commis sioners Shireves Coroners Eschetours Stewardes and their Lieuten'ntes, and all other Officers and Ministers ofthe Lawe, shall pclayme and kepe the Sessions Courtes ... and all other Courtes, in the Englisshe Tongue and all others of Officers Juries and Enquetes and all other affidavithes v~rdictes and wagers of 1. -

Commodore John Barry

Commodore John Barry Day, 13th September Commodore John Barry (1745-1803) a native of County Wexford, Ireland was a Continental Navy hero of the American War for Independence. Barry’s many victories at sea during the Revolution were important to the morale of the Patriots as well as to the successful prosecution of the War. When the First Congress, acting under the new Constitution of the United States, authorized the raising and construction of the United States Navy, President George Washington turned to Barry to build and lead the nation’s new US Navy, the successor to the Continental Navy. On 22 February 1797, President Washington conferred upon Barry, with the advice and consent of the Senate, the rank of Captain with “Commission No. 1,” United States Navy, effective 7 June 1794. Barry supervised the construction of his own flagship, the USS UNITED STATES. As commander of the first United States naval squadron under the Constitution, which included the USS CONSTITUTION (“Old Ironsides”), Barry was a Commodore with the right to fly a broad pennant, which made him a flag officer. Commodore John Barry By Gilbert Stuart (1801) John Barry served as the senior officer of the United States Navy, with the title of “Commodore” (in official correspondence) under Presidents George Washington, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. The ships built by Barry, and the captains selected, as well as the officers trained, by him, constituted the United States Navy that performed outstanding service in the “Quasi-War” with France, in battles with the Barbary Pirates and in America’s Second War for Independence (the War of 1812). -

Postgraduate Prospectus 2021 >90 Ostgraduate Prospectus 2021 SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT MULTI

National University of Ireland, Galway 175 Ollscoil na hÉireann, Gaillimh T +353 91 524 411 E [email protected] Prospectus 2021 Prospectus Postgraduate Postgraduate 2021 Prospectus National University of Ireland, Galway of Ireland, University National NUI Galway Campus Áras de Brún (School of Mathematics, Statistics and Applied Mathematics) Áras Uí Chathail/Student Information Desk (SID) Áras na Gaeilge The Quadrangle Áras na Mac Léinn and Bailey Allen Hall University Hospital Galway Lambe Institute for Translational Research and HRB Clinical Research Facility Pictured in the Quadrangle, NUI Galway, Sinéad Shaughnessy, scholarship recipient, master’s student 2019–20. Centre for Adult Learning and Professional Development Postgraduate Scholarships Scheme for full-time taught masters’ students At NUI Galway we are keen to ensure that the brightest and most committed students progress to postgraduate study. Our Postgraduate Scholarships are designed to reward excellent students who have performed exceptionally well in their undergraduate studies. Scholarships are worth €1,500 per student. Scholarships will be awarded to EU students who: Huston School of Film and Digital Media • Have been accepted on to a full-time taught master’s programme commencing September 2021 Martin Ryan Building (Environmental, Marine and Energy Research) • Have a First Class Honours undergraduate degree O’Donoghue Centre for Drama, Theatre and Performance More information/how to apply Human Biology Building www.nuigalway.ie/postgraduate_scholarships T: +353 91 -

Minority Language Rights: the Irish Language and Ulster Scots

MINORITY LANGUAGE RIGHTS The Irish language and Ulster Scots Briefing paper on the implications of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, European Convention on Human Rights and other instruments June 2010 © Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission Temple Court, 39 North Street Belfast BT1 1NA Tel: (028) 9024 3987 Fax: (028) 9024 7844 Textphone: (028) 90249066 SMS Text: 07786 202075 Email: [email protected] Website: www.nihrc.org 1 2 CONTENTS page Introduction 5 1. Development of minority language rights in international human rights law 6 1.1 The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages 7 1.2 Indigenous languages and the Charter, and obligations relating to ‘non-indigenous’ languages 8 1.3 The Irish language and Ulster Scots 10 2. Duties framework for public authorities 12 2.1 Duties in relation to the Irish language under Part III of the Charter 12 2.2 Policy Objectives and Principles for Irish and Ulster Scots under Part II of the Charter 13 2.3 The Belfast (Good Friday) and St Andrews Agreements 14 2.4 Minority language rights in UN and other Council of Europe instruments, including the European Convention on Human Rights 15 2.5 Duties and the policy development process 17 3. Non-discrimination on grounds of language 18 3.1 Human rights law obligations 18 3.2 Discrimination against English speakers? 19 3.3 Differential treatment of Irish and Ulster Scots 20 3.4 Banning or restricting minority languages 21 4. Positive action: promotion through corporate identity 25 4.1 Promotion of minority languages and the rights of others 25 4.2 Freedom of expression and ‘sensitivities’ 26 Appendix 1: The Charter, Article 10 29 Appendix 2: The Charter, Part II, Article 7 30 3 4 INTRODUCTION The Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission (the Commission) is a statutory body created by the Northern Ireland Act 1998. -

Seanad Éireann

Vol. 245 Wednesday, No. 7 27 January 2016 DÍOSPÓIREACHTAÍ PARLAIMINTE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES SEANAD ÉIREANN TUAIRISC OIFIGIÚIL—Neamhcheartaithe (OFFICIAL REPORT—Unrevised) Insert Date Here 27/01/2016A00100Business of Seanad 381 27/01/2016A00300Commencement Matters 381 27/01/2016A00400Wastewater Treatment 381 27/01/2016B00350Defence Forces Ombudsman Complaints 383 27/01/2016C01050Family Support Services 386 27/01/2016G00050Order of Business 389 27/01/2016S00100National Anthem (Protection of Copyright and Related Rights) (Amendment) Bill 2016: First Stage 407 27/01/2016S01000Death of Former Member: Expressions of Sympathy 408 27/01/2016Z00100Joint Committee of Inquiry into the Banking Crisis: Motion 419 27/01/2016Z00500Public Transport Bill 2015: Second Stage 419 27/01/2016GG00700Public Transport Bill 2015: Committee and Remaining Stages 434 27/01/2016JJ01300Direct Provision System: Motion 439 27/01/2016VV00100Horse Racing Ireland Bill 2015: Second Stage 462 27/01/2016FFF00300Horse