Ireland Homeland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ballinleenty Townland, Co. Tipperary

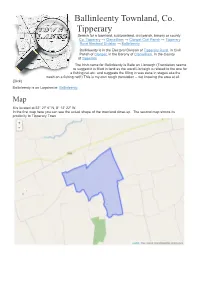

Ballinleenty Townland, Co. Tipperary Search for a townland, subtownland, civil parish, barony or countySearch Co. Tipperary → Clanwilliam → Clonpet Civil Parish → Tipperary Rural Electoral Division → Ballinleenty Ballinleenty is in the Electoral Division of Tipperary Rural, in Civil Parish of Clonpet, in the Barony of Clanwilliam, in the County of Tipperary The Irish name for Ballinleenty is Baile an Líontaigh (Translation seems to suggest it is filled in land as the word Líontaigh is related to the one for a fishing net etc. and suggests the filling in was done in stages aka the mesh on a fishing net!!) This is my own rough translation – not knowing the area at all. (Dick) Ballinleenty is on Logainm.ie: Ballinleenty. Map It is located at 52° 27' 6" N, 8° 12' 22" W. In the first map here you can see the actual shape of the townland close-up. The second map shows its proximity to Tipperary Town Leaflet | Map data © OpenStreetMap contributors Area Ballinleenty has an area of: 1,513,049 m² / 151.30 hectares / 1.5130 km² 0.58 square miles 373.88 acres / 373 acres, 3 roods, 21 perches Nationwide, it is the 17764th largest townland that we know about Within Co. Tipperary, it is the 933rd largest townland Borders Ballinleenty borders the following other townlands: Ardavullane to the west Ardloman to the south Ballynahow to the west Breansha Beg to the east Clonpet to the east Gortagowlane to the north Killea to the south Lackantedane to the east Rathkea to the west Subtownlands We don't know about any subtownlands in Ballinleenty. -

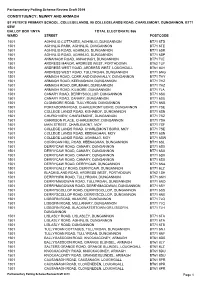

Constituency: Newry and Armagh

Parliamentary Polling Scheme Review Draft 2019 CONSTITUENCY: NEWRY AND ARMAGH ST PETER'S PRIMARY SCHOOL, COLLEGELANDS, 90 COLLEGELANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON, BT71 6SW BALLOT BOX 1/NYA TOTAL ELECTORATE 966 WARD STREET POSTCODE 1501 AGHINLIG COTTAGES, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6TD 1501 AGHINLIG PARK, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6TE 1501 AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6SR 1501 AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6SP 1501 ANNAHAGH ROAD, ANNAHAGH, DUNGANNON BT71 7JE 1501 ARDRESS MANOR, ARDRESS WEST, PORTADOWN BT62 1UF 1501 ARDRESS WEST ROAD, ARDRESS WEST, LOUGHGALL BT61 8LH 1501 ARDRESS WEST ROAD, TULLYROAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6NG 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, CORR AND DUNAVALLY, DUNGANNON BT71 7HY 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, KEENAGHAN, DUNGANNON BT71 7HZ 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, DRUMARN, DUNGANNON BT71 7HZ 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, KILMORE, DUNGANNON BT71 7JA 1501 CANARY ROAD, DERRYSCOLLOP, DUNGANNON BT71 6SU 1501 CANARY ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SU 1501 CLONMORE ROAD, TULLYROAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6NB 1501 PORTADOWN ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO, DUNGANNON BT71 7SE 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KISHABOY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SN 1501 CHURCHVIEW, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON BT71 7SZ 1501 GARRISON PLACE, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON BT71 7SA 1501 MAIN STREET, CHARLEMONT, MOY BT71 7SF 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO, MOY BT71 7SE 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KEENAGHAN, MOY BT71 6SN 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, AGHINLIG, MOY BT71 6SW 1501 CORRIGAN HILL ROAD, KEENAGHAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6SL 1501 DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SX 1501 DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SX 1501 DERRYCAW ROAD, -

Appendix A16.8 Townland Boundaries to Be Crossed by the Proposed Project

Environmental Impact Assessment Report: Volume 3 Part B of 6 Appendix A16.8 Townland Boundaries to be Crossed by the Proposed Project TB No.: 1 Townlands: Abbotstown/ Dunsink Parish: Castleknock Barony: Castleknock NGR: 309268, 238784 Description: This townland boundary is marked at the same location on all the OS map editions. It is formed by a road, which today have been truncated by the M50 to the south-east. The tarmac surface of the road is still present at this location, although overgrown. The road also separated the demesne associated with Abbotstown House and Hillbrook (DL 1, DL 2). Reference: OS mapping, field inspection TB No.: 2 Townlands: Dunsink/ Sheephill Parish: Castleknock Barony: Castleknock NGR: 309327, 238835 Description: This townland boundary is marked at the same location on all the OS map editions. It is formed by a road, which today have been truncated by the M50 to the south-east. The tarmac surface of the road is still present at this location, although overgrown. The road also separated the demesne associated with Abbotstown House (within the townland of Sheephill) and Hillbrook (DL 1, DL 2). The remains of a stone demesne wall associated with Abbotstown are located along the northern side of the road (UBH 2). Reference: OS mapping, field inspection 32102902/EIAR/3B Environmental Impact Assessment Report: Volume 3 Part B of 6 TB No.: 3 Townlands: Sheephill/ Dunsink Parish: Castleknock Barony: Castleknock NGR: 310153, 239339 Description: This townland boundary is marked at the same location on all the OS map editions. It is formed by a road, which today have been truncated by the M50 to the south. -

The Belfast Gazette, May 30, 1930. 683 1

THE BELFAST GAZETTE, MAY 30, 1930. 683 PROVISIONAL LIST No. 1689. LAND PURCHASE COMMISSION, NORTHERN IRELAND. NORTHERN IRELAND LAND ACT, 1925. ESTATE OF GEORGE SCOTT. County of Armagh. Record No. N.I. 1454. WHEREAS the above-mentioned George Scott claims to be the Owner of land in the Townlands of Annaclaie and Killuney, in the Barony of Oneilland West, and in the Townlands of Corporation, Drumadd, Ballynahone More, Knockaconey, and Tullygoonigan, Barony of Armagh, all in the County of Armagh. Now in pursuance of the provisions of Section 17, Sub-section 2, of the above Act the Land Purchase Commission Northern Ireland, hereby publish the following Provisional last of all land in the said Townlands of which the said George Scott claims to be the Owner, which will become vested in the said Commission by virtue of Part II of the Northern Ireland Land Act, 1925, on the Appointed Day to be hereafter fixed. Standard Standard No on Purchase Price Map filed Annuity if land Reg. Name of Tenant. Postal Address. Barony. Townland. In Land Area. Bent. if land becomes Purchase becomes vested No. Oommls- vested A. B. P. £ s. d.£ s. d. £ B. d Holdings subject to Judicial Bents fixed before the 16th August, 1896. 1 Anne McLaughlin : Tullygooni- Armagh Tullygooni- 3 5 1 20 4 10 03 3 2 66 9 10 (spinster) gan, gan Allistragh, Co. Armagh. 3 Do. do. do. do. 11, 11A 317 3 0 02 2 2 44 7.9 11B 11C 4 : Joseph McCrealy do. do. do. 12 2 0 20 1 15 01 4 6 25 15 9 5 John McArdle Knockaconey, do. -

![County Londonderry - Official Townlands: Administrative Divisions [Sorted by Townland]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6319/county-londonderry-official-townlands-administrative-divisions-sorted-by-townland-216319.webp)

County Londonderry - Official Townlands: Administrative Divisions [Sorted by Townland]

County Londonderry - Official Townlands: Administrative Divisions [Sorted by Townland] Record O.S. Sheet Townland Civil Parish Barony Poor Law Union/ Dispensary /Local District Electoral Division [DED] 1911 D.E.D after c.1921 No. No. Superintendent Registrar's District Registrar's District 1 11, 18 Aghadowey Aghadowey Coleraine Coleraine Aghadowey Aghadowey Aghadowey 2 42 Aghagaskin Magherafelt Loughinsholin Magherafelt Magherafelt Magherafelt Aghagaskin 3 17 Aghansillagh Balteagh Keenaght Limavady Limavady Lislane Lislane 4 22, 23, 28, 29 Alla Lower Cumber Upper Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Claudy Claudy 5 22, 28 Alla Upper Cumber Upper Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Claudy Claudy 6 28, 29 Altaghoney Cumber Upper Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Ballymullins Ballymullins 7 17, 18 Altduff Errigal Coleraine Coleraine Garvagh Glenkeen Glenkeen 8 6 Altibrian Formoyle / Dunboe Coleraine Coleraine Articlave Downhill Downhill 9 6 Altikeeragh Dunboe Coleraine Coleraine Articlave Downhill Downhill 10 29, 30 Altinure Lower Learmount / Banagher Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Banagher Banagher 11 29, 30 Altinure Upper Learmount / Banagher Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Banagher Banagher 12 20 Altnagelvin Clondermot Tirkeeran Londonderry Waterside Rural [Glendermot Waterside Waterside until 1899] 13 41 Annagh and Moneysterlin Desertmartin Loughinsholin Magherafelt Magherafelt Desertmartin Desertmartin 14 42 Annaghmore Magherafelt Loughinsholin Magherafelt Bellaghy Castledawson Castledawson 15 48 Annahavil Arboe Loughinsholin Magherafelt Moneymore Moneyhaw -

MODERN LIVING with a CLASSIC TWIST. MODERN LIVING with a Lacehill Is a Quality Manufacturer from Which Development Offering New It Derives Its Name

MODERN 3 & 4 BEDROOM DETACHED 3 & 4 BEDROOM HOMES AND SEMI DETACHED LIVING WITH A CLASSIC TWIST. PORTADOWN LOUGHGALL ROAD LOUGHGALL Location: PHASE 5 LACEHILL — PORTADOWN 1 MODERN LIVING WITH A CLASSIC TWIST. MODERN LIVING WITH A Lacehill is a quality manufacturer from which development offering new it derives its name. turnkey homes finished The development’s location CLASSIC to the highest standard. allows for ease of access to the Hilmark Homes have brought neighbouring towns whilst giving their experience and expertise commuters fantastic links to the TWIST. to Lacehill where they are Greater Belfast Area and beyond. building on the success of their Lacehill offers buyers already established developments contemporary and stylish, Bowens Mews, Lurgan; turnkey homes built with Spinners Court, Armagh; traditional craftsmanship. The Forge, Ballygowan and the prestigious Hartley Hall, Greenisland. Whether looking for your first home or just a fresh place to live, Lacehill is located on the Lacehill has a selection of quality Loughgall Road on the outskirts homes to suit all. of Portadown. The site was originally occupied by a lace 2 LACEHILL — PORTADOWN LACEHILL — PORTADOWN 3 SPECIFICATION HIGH As you would expect from such an outstanding STANDARD scheme, the comprehensive, modern turnkey specification of Lacehill offers the very best in terms of quality products and stylish finishes. FINISH Kitchens & Utility Rooms Internal Features • High quality units with choice of doors, worktops and handles • Internal décor, walls and ceilings painted -

Commodore John Barry

Commodore John Barry Day, 13th September Commodore John Barry (1745-1803) a native of County Wexford, Ireland was a Continental Navy hero of the American War for Independence. Barry’s many victories at sea during the Revolution were important to the morale of the Patriots as well as to the successful prosecution of the War. When the First Congress, acting under the new Constitution of the United States, authorized the raising and construction of the United States Navy, President George Washington turned to Barry to build and lead the nation’s new US Navy, the successor to the Continental Navy. On 22 February 1797, President Washington conferred upon Barry, with the advice and consent of the Senate, the rank of Captain with “Commission No. 1,” United States Navy, effective 7 June 1794. Barry supervised the construction of his own flagship, the USS UNITED STATES. As commander of the first United States naval squadron under the Constitution, which included the USS CONSTITUTION (“Old Ironsides”), Barry was a Commodore with the right to fly a broad pennant, which made him a flag officer. Commodore John Barry By Gilbert Stuart (1801) John Barry served as the senior officer of the United States Navy, with the title of “Commodore” (in official correspondence) under Presidents George Washington, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. The ships built by Barry, and the captains selected, as well as the officers trained, by him, constituted the United States Navy that performed outstanding service in the “Quasi-War” with France, in battles with the Barbary Pirates and in America’s Second War for Independence (the War of 1812). -

By Clare O' Hagan 8D

My Parish Project- Loughgall By Clare O’ Hagan 8D Parish Priest: Fr Eugene Sweeney 1 My Parish Project- Loughgall CONTENTS Page 3----------------------------------------------------------Letter to Paul Page 4----------------------------------------------------------My Parish contact details Page 5---------------------------------------------------------The Geography and History of Loughgall Parish Page 6---------------------------------------------------------The Location of Loughgall Parish Page 7---------------------------------------------------------Mass times in Loughgall Parish Page 8-11-----------------------------------------------------The Church Buildings Page 12----------------------------------------------------- -The Role of a Priest -Ordained Priests who are Natives of the Parish Page 13--------------------------------------------------------My Parish Priest Page 14--------------------------------------------------------Schools in Loughgall Parish Page 15-18----------------------------------------------------The Role of the Lay people in Loughgall Parish Page 19-20--------------------------------------------------------Activities and Clubs in Loughgall Parish Page 21--------------------------------------------------------Special Fundraising Effort 2013/2014 Page 22----------------------------------------Links between Loughgall Parish and St. Patrick’s Academy Page 23--------------------------------------------------------My Roles in My Parish Appendix 1-Christmas Mass Schedule Appendix 2-Parish Bulletin Appendix 3-Re-dedication -

Excavating Cartographic Encounters in Plantation Ireland Through GIS

Mapping Worlds? Excavating Cartographic Encounters in Plantation Ireland through GIS Keith Lilley and Catherine Porter School of Geography, Archaeology and Palaeoecology Queen’s University Belfast ABSTRACT: This paper uses the analytical potential of Geographical Information Systems (GIS) to explore processes of map production and circulation in early- seventeenth-century Ireland. The paper focuses on a group of historic maps attributed to Josias Bodley, which were commissioned in 1609 by the English Crown to assist in the Plantation of Ulster. Through GIS and digitizing map-features, and in particular by quantifying map-distortion, it is possible to examine how these maps were made, and by whom. Statistical analyses of spatial data derived from the GIS are shown to provide a methodological basis for “excavating” historical geographies of Plantation map-making. These techniques, when combined with contemporary written sources, reveal further insight on the “cartographic encounters” taking place between surveyors and map-makers working in Ireland in the early 1600s, opening up the “mapping worlds” which linked Ireland and Britain through the networks and embodied practices of Bodley and his map-makers. rom his lodging on the Strand in London in March 1610, Sir Thomas Ridgeway, the first earl of Londonderry, wrote a letter to the earl of Salisbury, Robert Cecil, then the lord treasurer Ffor England and the English Crown.1 Referring to maps “newly bound in six several books,” Ridgeway’s letter marked the end of a long enterprise, begun some eighteen months earlier, of surveying and mapping the Irish lands newly taken for plantation; the escheated counties of Ulster. -

Ulster-Scots

Ulster-Scots Biographies 2 Contents 1 Introduction The ‘founding fathers’ of the Ulster-Scots Sir Hugh Montgomery (1560-1636) 2 Sir James Hamilton (1559-1644) Major landowning families The Colvilles 3 The Stewarts The Blackwoods The Montgomerys Lady Elizabeth Montgomery 4 Hugh Montgomery, 2nd Viscount Sir James Montgomery of Rosemount Lady Jean Alexander/Montgomery William Montgomery of Rosemount Notable individuals and families Patrick Montgomery 5 The Shaws The Coopers James Traill David Boyd The Ross family Bishops and ministers Robert Blair 6 Robert Cunningham Robert Echlin James Hamilton Henry Leslie John Livingstone David McGill John MacLellan 7 Researching your Ulster-Scots roots www.northdowntourism.com www.visitstrangfordlough.co.uk This publication sets out biographies of some of the part. Anyone interested in researching their roots in 3 most prominent individuals in the early Ulster-Scots the region may refer to the short guide included at story of the Ards and north Down. It is not intended to section 7. The guide is also available to download at be a comprehensive record of all those who played a northdowntourism.com and visitstrangfordlough.co.uk Contents Montgomery A2 Estate boundaries McLellan Anderson approximate. Austin Dunlop Kyle Blackwood McDowell Kyle Kennedy Hamilton Wilson McMillin Hamilton Stevenson Murray Aicken A2 Belfast Road Adams Ross Pollock Hamilton Cunningham Nesbit Reynolds Stevenson Stennors Allen Harper Bayly Kennedy HAMILTON Hamilton WatsonBangor to A21 Boyd Montgomery Frazer Gibson Moore Cunningham -

Viscount Frankfort, Sir Charles Burton and County Carlow in the 1840S

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Norton, Desmond A. G. Working Paper Viscount Frankfort, Sir Charles Burton and county Carlow in the 1840s Centre for Economic Research Working Paper Series, No. WP01/20 Provided in Cooperation with: UCD School of Economics, University College Dublin (UCD) Suggested Citation: Norton, Desmond A. G. (2001) : Viscount Frankfort, Sir Charles Burton and county Carlow in the 1840s, Centre for Economic Research Working Paper Series, No. WP01/20, University College Dublin, Department of Economics, Dublin, http://hdl.handle.net/10197/1280 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/72434 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an -

Language Notes on Baronies of Ireland 1821-1891

Database of Irish Historical Statistics - Language Notes 1 Language Notes on Language (Barony) From the census of 1851 onwards information was sought on those who spoke Irish only and those bi-lingual. However the presentation of language data changes from one census to the next between 1851 and 1871 but thereafter remains the same (1871-1891). Spatial Unit Table Name Barony lang51_bar Barony lang61_bar Barony lang71_91_bar County lang01_11_cou Barony geog_id (spatial code book) County county_id (spatial code book) Notes on Baronies of Ireland 1821-1891 Baronies are sub-division of counties their administrative boundaries being fixed by the Act 6 Geo. IV., c 99. Their origins pre-date this act, they were used in the assessments of local taxation under the Grand Juries. Over time many were split into smaller units and a few were amalgamated. Townlands and parishes - smaller units - were detached from one barony and allocated to an adjoining one at vaious intervals. This the size of many baronines changed, albiet not substantially. Furthermore, reclamation of sea and loughs expanded the land mass of Ireland, consequently between 1851 and 1861 Ireland increased its size by 9,433 acres. The census Commissioners used Barony units for organising the census data from 1821 to 1891. These notes are to guide the user through these changes. From the census of 1871 to 1891 the number of subjects enumerated at this level decreased In addition, city and large town data are also included in many of the barony tables. These are : The list of cities and towns is a follows: Dublin City Kilkenny City Drogheda Town* Cork City Limerick City Waterford City Database of Irish Historical Statistics - Language Notes 2 Belfast Town/City (Co.