Major Glacial Drainage Changes in Ohio1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Midwestern Basins and Arches Regional Aquifer System in Parts of Indiana, Ohio, Michigan, and Illinois Summary

THE MIDWESTERN BASINS AND ARCHES REGIONAL AQUIFER SYSTEM IN PARTS OF INDIANA, OHIO, MICHIGAN, AND ILLINOIS SUMMARY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1423-A uses dence for a changing world Availability of Publications of the U.S. Geological Survey Order U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) publications from the Documents. Check or money order must be payable to the offices listed below. Detailed ordering instructions, along with Superintendent of Documents. Order by mail from prices of the last offerings, are given in the current-year issues of the catalog "New Publications of the U.S. Geological Superintendent of Documents Survey." Government Printing Office Washington, DC 20402 Books, Maps, and Other Publications Information Periodicals By Mail Many Information Periodicals products are available through Books, maps, and other publications are available by mail the systems or formats listed below: from Printed Products USGS Information Services Box 25286, Federal Center Printed copies of the Minerals Yearbook and the Mineral Com Denver, CO 80225 modity Summaries can be ordered from the Superintendent of Publications include Professional Papers, Bulletins, Water- Documents, Government Printing Office (address above). Supply Papers, Techniques of Water-Resources Investigations, Printed copies of Metal Industry Indicators and Mineral Indus Circulars, Fact Sheets, publications of general interest, single try Surveys can be ordered from the Center for Disease Control copies of permanent USGS catalogs, and topographic and and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and thematic maps. Health, Pittsburgh Research Center, P.O. Box 18070, Pitts burgh, PA 15236-0070. Over the Counter Mines FaxBack: Return fax service Books, maps, and other publications of the U.S. -

Indiana Glaciers.PM6

How the Ice Age Shaped Indiana Jerry Wilson Published by Wilstar Media, www.wilstar.com Indianapolis, Indiana 1 Previiously published as The Topography of Indiana: Ice Age Legacy, © 1988 by Jerry Wilson. Second Edition Copyright © 2008 by Jerry Wilson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 2 For Aaron and Shana and In Memory of Donna 3 Introduction During the time that I have been a science teacher I have tried to enlist in my students the desire to understand and the ability to reason. Logical reasoning is the surest way to overcome the unknown. The best aid to reasoning effectively is having the knowledge and an understanding of the things that have previ- ously been determined or discovered by others. Having an understanding of the reasons things are the way they are and how they got that way can help an individual to utilize his or her resources more effectively. I want my students to realize that changes that have taken place on the earth in the past have had an effect on them. Why are some towns in Indiana subject to flooding, whereas others are not? Why are cemeteries built on old beach fronts in Northwest Indiana? Why would it be easier to dig a basement in Valparaiso than in Bloomington? These things are a direct result of the glaciers that advanced southward over Indiana during the last Ice Age. The history of the land upon which we live is fascinating. Why are there large granite boulders nested in some of the fields of northern Indiana since Indiana has no granite bedrock? They are known as glacial erratics, or dropstones, and were formed in Canada or the upper Midwest hundreds of millions of years ago. -

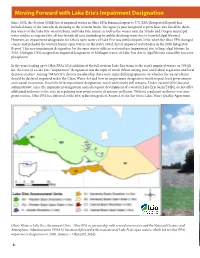

Moving Forward with Lake Erie's Impairment Designation

Moving Forward with Lake Erie’s Impairment Designation Since 2002, the Section 303(d) list of impaired waters in Ohio EPA’s biannual report to U.S. EPA (Integrated Report) has Policy Recommendations -Western Lake Erie Basin Impairment included many of the watersheds draining to the western basin. The agency’s past integrated reports have also listed the shore- line waters of the Lake Erie western basin and Lake Erie islands as well as the waters near the Toledo and Oregon municipal • To meet requirements under the Clean Water Act, TMACOG recommends that the U.S. EPA work collaboratively with the water intakes as impaired for all four beneficial uses (including for public drinking water due to harmful algal blooms). designated agencies of WLEB states – Ohio EPA, Michigan DEQ, and Indiana Office of Water Quality – to evaluate water However, an impairment designation for Ohio’s open waters of Lake Erie was withheld until 2018, when the Ohio EPA changed quality targets for open waters and set monitoring and assessment protocols that can be used to continue to evaluate the course and included the western basin’s open waters on the state’s 303(d) list of impaired waterbodies in the 2018 Integrated status for the four beneficial uses in the open waters of Lake Erie’s western basin. Report. This new impairment designation for the open waters adds recreational use impairment due to large algal blooms. In 2016, Michigan DEQ assigned an impaired designation to Michigan waters of Lake Erie due to algal blooms caused by excessive • If U.S. -

Biological and Water Quality Study of the Ashtabula River and Select Tributaries, 2011

Biological and Water Quality Study of the Ashtabula River and Select Tributaries, 2011 Ashtabula County Ashtabula River at Benetka Road (RM 19.03) OHIO EPA Technical Report EAS/2014-01-01 Division of Surface Water December 19, 2014 EAS/2014-01-01 Ashtabula River and Select Tributaries TSD December 19, 2014 Biological and Water Quality Survey of the Ashtabula River and Select Tributaries 2011 Ashtabula County December 19, 2014 Ohio EPA Technical Report EAS/2014-01-01 Prepared by: Ohio Environmental Protection Agency Division of Surface Water Lazarus Government Center 50 West Town Street, Suite 700 Columbus, Ohio 43215 Ohio Environmental Protection Agency Ecological Assessment Section 4675 Homer Ohio Lane Groveport, Ohio 43125 and Ohio Environmental Protection Agency Northeast District Office 2110 East Aurora Road Twinsburg, Ohio 44087 Mail to: P.O. Box 1049, Columbus, Ohio 43216-1049 John R. Kasich, Governor, State of Ohio Craig W. Butler, Director, Ohio Environmental Protection Agency i EAS/2014-01-01 Ashtabula River and Select Tributaries TSD December 19, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 12 STUDY AREA ........................................................................................................................... 13 RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................................................................................ -

2000 Lake Erie Lamp

Lake Erie LaMP 2000 L A K E E R I E L a M P 2 0 0 0 Preface One of the most significant environmental agreements in the history of the Great Lakes took place with the signing of the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement of 1978 (GLWQA), between the United States and Canada. This historic agreement committed the U.S. and Canada (the Parties) to address the water quality issues of the Great Lakes in a coordinated, joint fashion. The purpose of the GLWQA is to “restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the waters of the Great Lakes Basin Ecosystem.” In the revised GLWQA of 1978, as amended by Protocol signed November 18, 1987, the Parties agreed to develop and implement, in consultation with State and Provincial Governments, Lakewide Management Plans (LaMPs) for lake waters and Remedial Action Plans (RAPs) for Areas of Concern (AOCs). The LaMPs are intended to identify critical pollutants that impair beneficial uses and to develop strategies, recommendations and policy options to restore these beneficial uses. Moreover, the Specific Objectives Supplement to Annex 1 of the GLWQA requires the development of ecosystem objectives for the lakes as the state of knowledge permits. Annex 2 further indicates that the RAPs and LaMPS “shall embody a systematic and comprehensive ecosystem approach to restoring and protecting beneficial uses...they are to serve as an important step toward virtual elimination of persistent toxic substances...” The Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement specifies that the LaMPs are to be completed in four stages. These stages are: 1) when problem definition has been completed; 2) when the schedule of load reductions has been determined; 3) when P r e f a c e remedial measures are selected; and 4) when monitoring indicates that the contribution of i the critical pollutants to impairment of beneficial uses has been eliminated. -

The Maumee River Watershed and Algal Blooms in Lake Erie1 2

SESYNC Case Study The Maumee River Watershed and Algal Blooms in Lake Erie1 2 Ramiro Berardo3 & Ajay Singh4. Summary: The decay of Lake Erie’s environmental health and its impacts on local communities, including public health and the environment, was one of the focal events motivating the passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972. Despite the considerable improvement in water quality in the 1970s and 1980s because of implementation of agricultural best management practices to address soil erosion, seasonal algal blooms returned to Western Lake Erie. Potential causes of algal blooms may be a mixture of agricultural and urban practices that threaten ecological stability and public health for millions dependent on the lake for drinking water, tourism, and fisheries. For instance, in fall, 2014, national attention turned to the city of Toledo, Ohio as the city’s residents experienced disruption to city services such as access to potable water and certain medical services including child birth and surgery. For this case study we will study the relationship between human behavior and water quality impairments which lead to toxic algal blooms in the Western Lake Erie Basin, and in particular, the Maumee River Watershed. We will also review prior management and policy efforts of different stakeholders to improve water quality as well as issues surrounding the development of proposed policy and management changes. Multiple stakeholders from multiple states and Canadian provinces are involved in seeking solutions to the ongoing pollution problems. This case study will be ideal to examine how cooperation unfolds in the presence of collective action problems, and the interrelationships between human behavior and environmental outcomes. -

Indiana's Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement (GLWQA) Domestic Action Plan (DAP) for the Western Lake Erie Basin (WLEB)

Indiana’s Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement (GLWQA) DOMESTIC ACTION PLAN (DAP) for the WESTERN LAKE ERIE BASIN (WLEB) February 2018 INDIANA’S GREAT LAKES WATER QUALITY AGREEMENT DOMESTIC ACTION PLAN for the WESTERN LAKE ERIE BASIN Table of Contents FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 GOALS ............................................................................................................................................................................ 6 Timeframe to meet load reduction goals ........................................................................................................ 7 INDIANA’S PORTION OF THE WLEB ............................................................................................................................... 8 Land Use in the WLEB and Major Sources of Phosphorous ............................................................................ 8 WATERSHED PRIORITIZATION ..................................................................................................................................... 11 GUIDING PRINCIPLES FOR ACHIEVING WATER QUALITY IMPROVEMENTS ................................................................. 14 Point Sources/Regulated .............................................................................................................................. -

Glacial and Postglacial Deposits of Northeastern Ohio1

66 A. T. CROSS Vol. 88 Glacial and Postglacial Deposits of Northeastern Ohio1 JOHN P. SZABO, CHARLES H. CARTER, PIERRE W. BRUNO and EDWARD J. JONES, Department of Geology, University of Akron, Akron, OH 44325 ABSTRACT. Recent high levels of Lake Erie have produced severe erosion and mass wasting along the shore. At the same time they have created excellent exposures of glacial and postglacial deposits east of Cleveland, Ohio. Glacial deposits consist of an older "Coastal" till and the Late Wisconsinan Ashtabula Till, whereas postglacial deposits generally are gravels, sands and silts. Lithofacies of the Ashtabula Till exposed at Sims Park in Euclid, Ohio, include sheared, massive diamicts and resedimented diamicts. The lowest sheared massive diamict previously identified as the "Coastal" till possibly represents a lodgement till deposited by Ashtabula ice. Beach deposits at Mentor Headlands resulted from construction of manmade structures. At Camp Isaac Jogues, deltaic sands overlie a sequence of diamicts, which has an unusually high carbonate content when compared to other sections along the shore. The geometry of the overlying sands and the facies sequence strongly suggest a river-dominated deltaic system. Two sand pits in beach ridges (one at the Warren level and the other at the Arkona level) farther inland contain coarse-grained facies that may rep- resent an outwash plain or coastal barrier overlain by dune sand. A log dated at 13-4 ka was found at the Arkona level, 1 km south of the second pit. OHIO J. SCI. 88 (1): 66-74, 1988 'Manuscript received 15 September 1987 and in revised form 7 December 1987 (#87-38). -

Characterization of Canadian Watersheds in the Lake Erie Basin

Characterization of Canadian watersheds in the Lake Erie basin Canada-Ontario Agreement on Great Lakes Water Quality and Ecosystem Health, 2014 (COA) Nutrient Annex Committee Science Subcommittee February 14, 2017 Background The COA Nutrient Annex Committee (NAC) is responsible for implementing COA Annex 1 - Nutrients including developing the Canada-Ontario Action Plan for Lake Erie that will outline how we will work collaboratively with our partners to meet phosphorus load reduction targets and reduce algal blooms in Lake Erie. Science Subcommittee • Subcommittee under COA NAC was directed to compile and assess existing data and information to characterize geographic areas within the Canadian side of the Lake Erie basin • Includes staff from 5 federal and provincial agencies 2 Background COA NAC Science Subcommittee: • Pamela Joosse, Natalie Feisthauer – Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) • Jody McKenna, Brad Bass – Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) • Mary Thorburn, Ted Briggs, Pradeep Goel, Matt Uza, Cheriene Vieira – Ontario Ministry of the Environment and Climate Changes (MOECC) • Dorienne Cushman – Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) • Jenn Richards, Tom MacDougall – Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (MNRF) 3 How to characterize the Lake Erie Basin? Land Use in the Lake Erie Basin (2010) Lake Erie Basin Characterization Quaternary watersheds in the Canadian Lake Erie basin were characterized according to the Canadian basin-wide distribution of distinguishing land cover/activities -

Phylogeography of Smallmouth Bass (Micropterus Dolomieu)

PHYLOGEOGRAPHY OF SMALLMOUTH BASS (MICROPTERUS DOLOMIEU) AND COMPARATIVE MYOLOGY OF THE BLACK BASS (MICROPTERUS, CENTRARCHIDAE) WILLIAM CALVIN BORDEN Bachelor of Science in Zoology University of Toronto Toronto, Ontario 1991 Master of Science in Zoology University of Toronto Toronto, Ontario 1996 Submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN REGULATORY BIOLOGY at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY May, 2008 This dissertation has been approved for the Department of Biological, Geological, and Environmental Sciences and for the College of Graduate Studies by Date: Dr. Miles M. Coburn, Department of Biology, John Carroll University Co-advisor Date: Dr. Robert A. Krebs, BGES/CSU Co-advisor Date: Dr. Clemencia Colmenares, The Cleveland Clinic Advisory Committee Member Date: Dr. F. Paul Doerder, BGES/CSU Advisory Committee Member Date: Dr. Harry van Keulen, BGES/CSU Internal Examiner Date: Dr. Mason Posner, Department of Biology, Ashland University External Examiner One fish two fish red fish blue fish. Black fish blue fish old fish new fish. This one has a little star. This one has a little car. Say! what a lot of fish there are. — Dr. Seuss, One fish two fish red fish blue fish ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many people were involved in the completion of this work. Firstly, numerous groups and individuals provided tissue samples of smallmouth bass and other fishes. They include J. McClain, A. Bowen, and A. Kowalski (USFWS – Alpena, MI); L. Witzel, A. Cook, E. Arnold, and E. Wright (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources – Lake Erie Management Unit); J. Hoyle (OMNR – Lake Ontario Management Unit); M. Nadeau and D. Gonder (OMNR – Upper Great Lakes Management Unit); K. -

Wetlands in Teays-Stage Valleys in Extreme Southeastern Ohio: Formation and Flora

~ Symposium on Wetlands of th'e Unglaclated Appalachian Region West Virginia University, Margantown, W.Va., May 26-28, 1982 Wetlands in Teays-stage Valleys in Extreme Southeastern Ohio: Formation and Flora David ., M. Spooner 1 Ohio Department of Natural Resources Fountain Square, Building F Columbus, Ohio 43224 ABSTRACT. A vegetational survey was conducted of Ohio wetlands within an area drained by the preglacial Marietta River (the main tributary of the Teays River in southeastern Ohio) and I along other tributaries of the Teays River to the east of the present-day Scioto River and south of the Marietta River drainage. These wetlands are underlain by a variety of poorly drained sediments, including pre-Illinoian lake silts, Wisconsin lake silts, Wisconsin glacial outwash, and recent alluvium. A number of rare Ohio species occur in these wetlands. They include I Potamogeton pulcher, Potamogeton tennesseensis, Sagittaria australis, Carex debilis var. debilis, Carex straminea, Wo(f(ia papu/({era, P/atanthera peramoena, Hypericum tubu/osum, Viola lanceo/ata, Viola primu/({o/ia, HO/lonia in/lata, Gratio/a virginiana, Gratiola viscidu/a var shortii and Utriculariagibba. In Ohio, none of thesewetlandsexist in their natural state. ~ They have become wetter in recent years due to beaver activity. This beaver activity is creating J open habitats that may be favorable to the increase of many of the rare species. The wetlandsare also subject to a variety of destructive influences, including filling, draining, and pollution from adjacent strip mines. All of the communities in these wetlands are secondary. J INTRODUCTION Natural Resources, Division of Natural Areas and Preserves, 1982. -

Lake Erie Environme Ntal Objectives

Lake Erie Environmental Objectives Report of the Environmental Objectives Sub-Committee of the LAKE ERIE COMMI TTEE Great Lakes Fishery Commission July, 2005 Subcommittee Members: David Davies Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ret.) Bob Haas Michigan Department of Natural Resources Larry Halyk Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources Roger Kenyon Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission Scudder Mackey University of Windsor Jim M arkham New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Ed Roseman USGS-Great Lakes Science Center Phil Ryan Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (ret) Jeff Tyson Ohio Department of Natural Resources Elizabeth Wright Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources Lake Erie Environmental Objectives Report of the Environmental Objectives Sub-Committee of the LAKE ERIE COMMI TTEE Great Lakes Fishery Commission July, 2005 Subcommittee Members: David Davies Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ret.) Bob Haas Michigan Department of Natural Resources Larry Halyk Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources Roger Kenyon Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission Scudder Mackey University of Windsor Jim M arkham New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Ed Roseman USGS-Great Lakes Science Center Phil Ryan Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (ret) Jeff Tyson Ohio Department of Natural Resources Elizabeth Wright Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS.................................................................................................................2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..............................................................................................................3