Celebrated Crimes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Five Fair Sisters; an Italian Episode at the Court of Louis

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Cornell University Library DC 130.M3W72 1906a Five fair sisters; 3 1924 028 182 495 The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924028182495 KS. ^ FIVE FAIR SISTERS AN ITALIAN EPISODE AT THE COURT OF LOUIS XIV BY H. NOEL WILLIAMSy AUTHOR OF ' MADAME r£CAM1ER AND HER FRIENDS," " MADAME DE POMPADOUR)' "MADAME DE MONTESPAN," "MADAME DU BAREV," "queens OP THE FRENCH STAGE," "LATER QUEENS OF THE FRENCH STAGE," ETC. WITH PHOTOGRAVURE PLATE AND SIXTEEN OTHER ILLUSTRATIONS NEW YORK G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS 27 & 29 WEST 23RD STREET igo6 Printed in Great Britain TO MY WIFE LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS HORTENSE MANCINI, DUCHESSE DE MAZARIN Frontispiece (Photogravure) From an engraving after the painting by Sir Peter Lely. TO FACE PAGE CARDINAL MAZARIN lO From an engraving after the painting by Mignard. ARMAND DE BOURBON, PRINCE DE CONTJ 38 From an engraving by Frosne. ANNE MARIE MARTINOZZI, PRINCESS DE CONTI . 40 From an engraving after the painting by Beaubrun. LAURE MANCINI, DUCHESSE DE MERCCEUR 58 From a contemporary print. LOUIS XIV 72 From an engraving after the drawing by Wallerant Vaillant. MARIE MANCINI IIO From an engraving after the painting by Sir Peter Leiy. ANNE OF AUSTRIA, QUEEN OF FRANCE 1 58 From an engraving af^er the painting by Mignard. PRINCE CHARLES (AFTER CHARLES v) OF LORRAINE . 200 From an engraving by Nanteuil. MARIA THERESA, QUEEN OF FRANCE 220 From an engraving after the painting by Beaubrun. -

La Culture Théologique Et Juridique De Edme Pirot, Confesseur De La Marquise De Brinvilliers (1676)

UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL GÉNÉALOGIE D'UNE EXHORTATION : LA CULTURE THÉOLOGIQUE ET JURIDIQUE DE EDME PIROT, CONFESSEUR DE LA MARQUISE DE BRINVILLIERS (1676) MÉMOIRE PRÉSENTÉ COMME EXIGENCE PARTIELLE DE LA MAÎTRISE EN HISTOIRE PAR KARINE GEMME MAI 2007 UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL Service des bibliothèques · Avertissement La diffusion de ce mémoire se fait dans le' respect des droits de son auteur, qui a signé le formulaire Autorisation de reproduire et de diffuser un travail de recherche de cycles supérieurs (SDU-522- Rév.01-2006). Cette autorisation stipule que «conformément à l'article 11 du Règlement no 8 des études de cycles supérieurs, [l'auteur] concède à l'Université du Québec à Montréal une licence non exclusive d'utilisation et de . publication oe la totalité ou d'une partie importante de [son] travail de recherche pour des fins pédagogiques et non commerciales. Plus précisément, [l'auteur] autorise l'Université du Québec à Montréal à reproduire, diffuser, prêter, distribuer ou vendre des · copies de. [son] travail de recherche à des fins non commerciales sur quelque support que ce soit, y compris l'Internet. Cette licence et cette autorisation n'entraînent pas une renonciation de [la] part [de l'auteur] à [ses] droits moraux ni à [ses] droits de propriété intellectuelle. Sauf. entente contraire, [l'auteur]. conserve la liberté de diffuser et de commercialiser ou non ce travail dont [il] possède un exemplaire ..» ------ ----- ----------------- ----- --------- - -------· ---------------------- - ----- REMERCIEMENTS Mes remerciements vont d'abord à mon directeur, Pascal Basti en, dont le dévouement fut exemplaire. Il a dirigé ce présent mémoire avec patience et enthousiasme. Ce travail n'a été possible que par ses efforts conjugués aux mi ens. -

La Marquise De Brinvilliers, 1676

LA MARQUISE DE BRINVILLIERS, 1676. Alexandre DUMAS-Père Texte établi par Laurent Angard (Université de Haute-Alsace, 2010) Vers la fin de l'année 1665, par une belle soirée d'automne, un rassemblement considérable était attroupé sur la partie du Pont-Neuf qui redescend vers la rue Dauphine 1. L'objet qui en formait le centre, et qui attirait sur lui l'attention publique, était un carrosse exactement fermé, dont un exempt 2 s'efforçait d'ouvrir la portière, tandis que, des quatre sergents qui formaient sa suite, deux arrêtaient les chevaux, en même temps que les deux autres contenaient le cocher, qui, sourd aux sommations faites, n'y avait répondu qu'en essayant de mettre son attelage au galop. Cette espèce de lutte durait depuis quelque temps déjà, lorsque tout-à-coup un des panneaux s'ouvrit avec violence, et un jeune officier, revêtu de l'uniforme de capitaine de cavalerie, sauta sur le pavé, refermant du même coup la portière qui venait de lui donner passage, mais point si vivement encore, que ceux qui étaient les plus rapprochés n'eussent eu le temps de distinguer au fond du carrosse, enveloppée dans une mante 3 et couverte d'un voile, une femme qui, aux précautions qu'elle avait prises de dérober son visage à tous les yeux, paraissait avoir lu plus grand intérêt à rester inconnue. — Monsieur, dit le jeune homme, s’adressant d'un ton hautain et impératif à l'exempt, comme je présume qu'à moins de méprise, c'est à moi seul que vous avez affaire, je vous prierai de me faire connaître les pouvoirs en vertu desquels vous avez arrêté ce carrosse où j'étais ; et maintenant que je n'y suis plus, je vous somme de donner l'ordre à vos gens de lui laisser continuer sa route. -

L'affaire Des Poisons : Entre Science Et Littérature, Une Ressource Pour L

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by HAL-ENS-LYON L’affaire des poisons : entre science et litt´erature,une ressource pour l'enseignement Philippe Jaussaud To cite this version: Philippe Jaussaud. L’affaire des poisons : entre science et litt´erature, une ressource pour l'enseignement. article publi´e dans la revue ´electronique L@bsolu octobre 2013. http://labsolus2hep.univ-lyon1.fr.. 2013. <halshs-00868682> HAL Id: halshs-00868682 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00868682 Submitted on 1 Oct 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L'archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destin´eeau d´ep^otet `ala diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publi´esou non, lished or not. The documents may come from ´emanant des ´etablissements d'enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche fran¸caisou ´etrangers,des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou priv´es. L’AFFAIRE DES POISONS : ENTRE SCIENCE ET LITTÉRATURE, UNE RESSOURCE POUR L’ENSEIGNEMENT !"#$#%%&'()*++)*,' EA 4148 Sciences et Société : Historicité, Éducation, Pratiques (S2HEP) Université Lyon 1. ([email protected]) Dans une nouvelle intitulée « L’entonnoir de cuir »1, Arthur Conan Doyle évoque une hypothèse originale : dormir à côté d’un objet ancien permettrait de vivre en rêve un événement historique lié à l’objet en question. Le héros de la nouvelle réalise l’expérience avec un entonnoir de cuir, acquis par un ami collectionneur. -

Étude De La Plausibilité Sémiologique De La Description Des Empoisonnements Dans Treize Écrits D’Alexandre Dumas Père Morgane Sladeczek

Étude de la plausibilité sémiologique de la description des empoisonnements dans treize écrits d’Alexandre Dumas père Morgane Sladeczek To cite this version: Morgane Sladeczek. Étude de la plausibilité sémiologique de la description des empoisonnements dans treize écrits d’Alexandre Dumas père. Médecine humaine et pathologie. 2019. dumas-02494524 HAL Id: dumas-02494524 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02494524 Submitted on 28 Feb 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITE DE BORDEAUX UFR DES SCIENCES MEDICALES Année 2019 N° 46 Thèse pour l’obtention du DIPLOME D’ETAT DE DOCTEUR EN MEDECINE SPECIALITÉ MEDECINE GENERALE Présentée et soutenue publiquement le lundi 29 avril 2019 Par Morgane SLADECZEK Née le 1 février 1987 à Montpellier (34) Etude de la plausibilité sémiologique de la description des empoisonnements dans treize écrits d’Alexandre Dumas père Directrice de thèse : Madame le docteur Magali LABADIE Jury de thèse : - Monsieur le Professeur Mathieu MOLIMARD : Président du Jury - Monsieur le Professeur Philippe REVEL : Rapporteur - Monsieur le Professeur Philippe CASTERA : Juge - Monsieur le docteur Guillaume VALDENAIRE : Juge 1 SOMMAIRE SERMENT D’HIPPOCRATE .................................................................................................. 6 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 9 1.1. Alexandre Dumas, sa biographie, son œuvre ........................................................ -

Criminal Poisoning FORENSIC SCIENCE- AND- MEDICINE

Criminal Poisoning FORENSIC SCIENCE- AND- MEDICINE Steven B. Karch, MD, SERIES EDITOR CRIMINAL POISONING: INVESTIGATIONAL GUIDE FOR LAW ENFORCEMENT, TOXICOLOGISTS, FORENSIC SCIENTISTS, AND ATTORNEYS, SECOND EDITION, by John H. Trestrail, III, 2007 MARIJUANA AND THE CANNABINOIDS, edited by Mahmoud A. ElSohly, 2007 FORENSIC PATHOLOGY OF TRAUMA: COMMON PROBLEMS FOR THE PATHOLOGIST, edited by Michael J. Shkrum and David A. Ramsay, 2007 THE FORENSIC LABORATORY HANDBOOK: PROCEDURES AND PRACTICE, edited by Ashraf Mozayani and Carla Noziglia, 2006 SUDDEN DEATHS IN CUSTODY, edited by Darrell L. Ross and Ted Chan, 2006 DRUGS OF ABUSE: BODY FLUID TESTING, edited by Raphael C. Wong and Harley Y. Tse, 2005 A PHYSICIAN’S GUIDE TO CLINICAL FORENSIC MEDICINE: SECOND EDITION, edited by Margaret M. Stark, 2005 FORENSIC MEDICINE OF THE LOWER EXTREMITY: HUMAN IDENTIFICATION AND TRAUMA ANALYSIS OF THE THIGH, LEG, AND FOOT, by Jeremy Rich, Dorothy E. Dean, and Robert H. Powers, 2005 FORENSIC AND CLINICAL APPLICATIONS OF SOLID PHASE EXTRACTION, by Michael J. Telepchak, Thomas F. August, and Glynn Chaney, 2004 HANDBOOK OF DRUG INTERACTIONS: A CLINICAL AND FORENSIC GUIDE, edited by Ashraf Mozayani and Lionel P. Raymon, 2004 DIETARY SUPPLEMENTS: TOXICOLOGY AND CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, edited by Melanie Johns Cupp and Timothy S. Tracy, 2003 BUPRENOPHINE THERAPY OF OPIATE ADDICTION, edited by Pascal Kintz and Pierre Marquet, 2002 BENZODIAZEPINES AND GHB: DETECTION AND PHARMACOLOGY, edited by Salvatore J. Salamone, 2002 ON-SITE DRUG TESTING, edited by Amanda J. Jenkins and Bruce A. Goldberger, 2001 BRAIN IMAGING IN SUBSTANCE ABUSE: RESEARCH, CLINICAL, AND FORENSIC APPLICATIONS, edited by Marc J. Kaufman, 2001 CRIMINAL POISONING INVESTIGATIONAL GUIDE FOR LAW ENFORCEMENT, TOXICOLOGISTS, FORENSIC SCIENTISTS, AND ATTORNEYS Second Edition John Harris Trestrail, III, RPh, FAACT, DABAT Center for the Study of Criminal Poisoning, Grand Rapids, MI © 2007 Humana Press Inc. -

Secret Societies

CHAPTER I THE ANCIENT SECRET TRADITION The East is the cradle of secret societies. For whatever end they may have been employed, the inspiration and methods of most of those mysterious associations which have played so important a part behind the scenes of the world's history will be found to have emanated from the lands where the first recorded acts of the great human drama were played out - Egypt, Babylon, Syria, and Persia. On the one hand Eastern mysticism, on the other Oriental love of intrigue, framed the systems later on to be transported to the West with results so tremendous and far-reaching. In the study of secret societies we have then a double line to follow - the course of associations enveloping themselves in secrecy for the pursuit of esoteric knowledge, and those using mystery and secrecy for an ulterior and, usually, a political purpose. But esotericism again presents a dual aspect. Here, as in every phase of earthly life, there is the revers de la médaille - white and black, light and darkness, the Heaven and Hell of the human mind. The quest for hidden knowledge may end with initiation into divine truths or into dark and abominable cults. Who knows with what forces he may be brought in contact beyond the veil? Initiation which leads to making use of spiritual forces, whether good or evil, is therefore capable of raising man to greater heights or of degrading him to lower depths than he could ever have reached by remaining on the purely physical plane. And when men thus unite themselves in associations, a collective force is generated which may exercise immense influence over the world around. -

Crimes Célèbres La Marquise De Brinvilliers

CRIMES CÉLÈBRES LA MARQUISE DE BRINVILLIERS ALEXANDRE DUMAS CRIMES CÉLÈBRES La marquise de Brinvilliers 1676 LE JOYEUX ROGER 2011 Cette édition a été établie à partir celle de Administration de la librairie, Paris, 1839-1842, en 8 tomes. Nous avons modernisé l’orthographe et la ponctuation. ISBN : 978-2-923523-88-0 Éditions Le Joyeux Roger Montréal [email protected] Vers la fin de l’année 1665, par une belle soirée d’automne, un rassemblement considérable était attroupé sur la partie du Pont-Neuf qui redescend vers la rue Dauphine. L’objet qui en formait le centre et qui attirait sur lui l’attention publique était un carrosse exactement fermé dont un exempt s’efforçait d’ouvrir la portière, tandis que, des quatre sergents qui formaient sa suite, deux arrêtaient les chevaux, en même temps que les deux autres contenaient le cocher, qui, sourd aux sommations faites, n’y avait répondu qu’en essayant de mettre son attelage au galop. Cette espèce de lutte durait depuis quelque temps déjà, lorsque tout à coup, un des panneaux s’ouvrit avec violence, et un jeune offi- cier, revêtu de l’uniforme de capitaine de cavalerie, sauta sur le pavé, refermant du même coup la portière qui venait de lui don- ner passage, mais point si vivement encore que ceux qui étaient les plus rapprochés n’eussent eu le temps de distinguer au fond du carrosse, enveloppée dans une mante et couverte d’un voile, une femme qui, aux précautions qu’elle avait prises de dérober son visage à tous les yeux, paraissait avoir le plus grand intérêt à rester inconnue. -

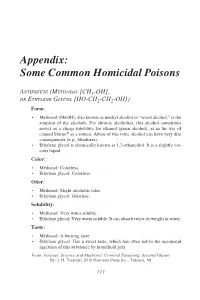

Appendix: Some Common Homicidal Poisons

Appendix 111 Appendix: Some Common Homicidal Poisons ANTIFREEZE (METHANOL [CH3-OH], OR ETHYLENE GLYCOL [HO-CH2-CH2-OH]) Form: • Methanol (MeOH), also known as methyl alcohol or “wood alcohol,” is the simplest of the alcohols. For chronic alcoholics, this alcohol sometimes serves as a cheap substitute for ethanol (grain alcohol), as in the use of canned Sterno® as a source. Abuse of this toxic alcohol can have very dire consequences (e.g., blindness). • Ethylene glycol is chemically known as 1,2-ethanediol. It is a slightly vis- cous liquid. Color: • Methanol: Colorless. • Ethylene glycol: Colorless. Odor: • Methanol: Slight alcoholic odor. • Ethylene glycol: Odorless. Solubility: • Methanol: Very water soluble. • Ethylene glycol: Very water soluble. It can absorb twice its weight in water. Taste: • Methanol: A burning taste. • Ethylene glycol: Has a sweet taste, which has often led to the accidental ingestion of this substance by household pets. From: Forensic Science and Medicine: Criminal Poisoning, Second Edition By: J. H. Trestrail, III © Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ 111 112 Common Homicidal Poisons Source: • Methanol: Is a common ingredient in windshield-washing solutions, dupli- cating fluids, and paint removers and is commonly found in gas-line anti- freeze, which may be 95% (v/v) methanol. • Ethylene glycol: Is commonly found in radiator antifreeze (in a concentration of ~95% [v/v]), and antifreeze products used in heating and cooling systems. Lethal Dose: • Methanol: The fatal dose is estimated to be 30–240 mL (20–150 g). • Ethylene glycol: The approximate fatal dose of 95% ethylene glycol is esti- mated to be 1.5 mL/kg. -

L'affaire Des Poisons : Les Origines Du Satanisme

L’AFFAIRE DES POISONS : LES ORIGINES DU SATANISME par Daniel Cardinal Thèse de maîtrise présentée au département d’études anciennes et de sciences des religions de la Faculté des Arts de l’Université d’Ottawa. © Daniel Cardinal, Ottawa, Canada, 2021 Résumé L’affaire des poisons est une célèbre enquête policière qui se déroula à la fin du XVIIe siècle en France sous le règne de Louis XIV. Les rapports officiels de la police de l’époque allaient dévoiler l’implication de membres des plus hautes sphères de la société française, y compris du clergé, du parlement, de la noblesse et de l’aristocratie. Mais l’enquête fut rapidement mise sous silence lorsque le roi découvrit l’implication de son ancienne maitresse en titre, la marquise de Montespan, avec qui il avait passé neuf ans de sa vie. Le nom de la dame fut mentionné par de nombreux témoins qui l’impliquèrent dans plusieurs méfaits, dont l’achat et l’utilisation de philtres d’amour et de divers poisons. Mais pis encore, Montespan fut compromise dans des cérémonies de nature blasphématoires organisées en secret par une devineresse du nom de Catherine Montvoisin - dites la Voisin - et son complice, l’abbé Étienne Guibourg. Ces rituels allaient plus tard prendre le nom de messe noire et inspirer une nouvelle forme de religiosité qui allait prendre le nom de satanisme. À partir des éléments révélés durant l’enquête de l’affaire des poisons, le satanisme allait pour la première fois se distinguer des pratiques de la sorcellerie et de la magie rituelle et se définir en tant que système de croyances. -

Alexandre Dumas LES CRIMES CÉLÈBRES

Alexandre Dumas LES CRIMES CÉLÈBRES La marquise de Brinvilliers La comtesse de Saint-Géran Jeanne de Naples Vaninka 1839-40 édité par les Bourlapapey, bibliothèque numérique romande www.ebooks-bnr.com Table des matières LA MARQUISE DE BRINVILLIERS 1676 ....... 3 LA COMTESSE DE SAINT-GÉRAN ............ 158 JEANNE DE NAPLES 1343-1382 ............... 249 VANINKA 1800-1801 ................................. 444 Ce livre numérique ........................................ 554 LA MARQUISE DE BRINVILLIERS 1676 Vers la fin de l’année 1665, par une belle soirée d’automne, un rassemblement considérable était attroupé sur la partie du pont Neuf qui redescend vers la rue Dauphine. L’objet qui en formait le centre, et qui attirait sur lui l’attention publique, était un carrosse exac- tement fermé, dont un exempt s’efforçait d’ouvrir la portière, tandis que, des quatre sergents qui formaient sa suite, deux arrêtaient les chevaux, en même temps que les deux autres contenaient le cocher, qui, sourd aux sommations faites, n’y avait répondu qu’en essayant de mettre son attelage au galop. Cette espèce de lutte durait depuis quelque temps déjà, lorsque tout à coup un des panneaux s’ouvrit avec violence, et un jeune officier, revêtu de l’uniforme de capitaine de cavalerie, sauta sur le pavé, refermant du même coup la portière qui – 3 – venait de lui donner passage, mais point si vive- ment encore, que ceux qui étaient les plus rappro- chés n’eussent eu le temps de distinguer au fond du carrosse, enveloppée dans une mante et cou- verte d’un voile, une femme qui, aux précautions qu’elle avait prises de dérober son visage à tous les yeux, paraissait avoir le plus grand intérêt à rester inconnue. -

Potions, Poisons and •Œinheritance Powdersâ•Š

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Chapman University Digital Commons Voces Novae Volume 4 Article 2 2018 Potions, Poisons and “Inheritance Powders”: How Chemical Discourses Entangled 17th Century France in the Brinvilliers Trial and the Poison Affair Erika Carroll Chapman University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/vocesnovae Recommended Citation Carroll, Erika (2018) "Potions, Poisons and “Inheritance Powders”: How Chemical Discourses Entangled 17th Century France in the Brinvilliers Trial and the Poison Affair," Voces Novae: Vol. 4 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/vocesnovae/vol4/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Voces Novae by an authorized editor of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Carroll: Potions, Poisons and “Inheritance Powders”: How Chemical Discours Potions, Poisons and “Inheritance Powders” Voces Novae: Chapman University Historical Review, Vol 3, No 1 (2012) HOME ABOUT USER HOME SEARCH CURRENT ARCHIVES PHI ALPHA THETA Home > Vol 3, No 1 (2012) > Carroll Potions, Poisons and "Inheritance Powders": How Chemical Discourses Entangled 17th Century France in the Brinvilliers Trial and the Poison Affair. Erika Carroll The trial of the Marquise de Brinvilliers for poisoning her father and her two brothers has long attracted the attention of historians as a prelude to the more famous Affair of the Poisons two years later. At the Marquise' execution, famed seventeenth-century chronicler Madame de Sevigné commented that her "ashes were to the winds, so that we shall breathe her, and ...we shall develop a poisoning urge which will astonish us all."[1] Madame de Sévingé's prediction was correct; France did develop a "poisoning urge" as a result of a growing interest in chemicals.