Nomination in the 2008 Legislative Election

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Tourist Publication Change of Kaohsiung City from the Prespective of Territory Change

International Journal of Management and Applied Science, ISSN: 2394-7926 Volume-4, Issue-10, Oct.-2018 http://iraj.in OFFICIAL TOURIST PUBLICATION CHANGE OF KAOHSIUNG CITY FROM THE PRESPECTIVE OF TERRITORY CHANGE 1HUEI-JU CHEN, 2JIA SIANG CHEN 1Professor, Department of Leisure and Recreation Management, National Kaohsiung University of Hospitality and Tourism, Kaohsiung, Taiwan 2Graduated student, Master Program in Transportation and Leisure Service Management, National Kaohsiung University of Hospitality and Tourism, Kaohsiung, Taiwan. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: The global visibility of Kaohsiung City, Taiwan is expecting by publishing international version of Kaohsiung publications, and expanding to the international channels. In 2010, Kaohsiung City’s territory was re-planned, which was an important milestone to establish a metropolise by county/city merger. Align with the county/city merging, the publication of original Kaohsiung County, namely “Kaohsiung County Today” was discontinued, and that of original Kaohsiung City, namely “Kaohsiung Pictorial” was also integrated into the publication of the new Kaohsiung County administrative region. Besides, the layout design of such publication was turned into the layout with a standard specification and a uniform style. In 2015, the existing publication was integrated and revised into “KH STYLE”. Therefore, this study attempts to understand the difference in the layout designs between the republished “Kaohsiung Pictorial” and the current “KH STYLE ", as well as summarize their style evolution before and after the merger of Kaohsiung County/City. This study used the content analysis to explore the elements included in the layout design as the manifestation and classified samples in the classification table. -

Study on the Shoot Characteristic and Madetea Quality of Rare Local

Study on the Shoot Characteristic and MadeTea Quality of Rare Local Cultivars Hun-Yuan Cheng Horng-Jey Fan1,* The purpose of this experiment was to understand the tea shoot characteristic, made tea quality and chemical composition of rare local cultivars, for the establishment of the production and manufacture technology achieve to develop special tea production. Experimental cultivars were including eleven local cultivars and two control cultivars for the shoot characteristics, made tea quality, chemical composition analysis. The experimental result showed that the catechin contents of Dah Nan Wan Bair Mau Hour and Bair Mau Hour were higher than other local cultivars. The EGCG content of Bair Mau Hour cultivar series was up to 80 mg/g. Heh Mau Hour and Bair Mau Hour cultivar series had more higher tea quality, Bian Joong Oolong also had best tea quality, Jy Lan cultivar series, Shiang Yuan, Gau Lu had slightly lower quality. Key words: Tea tree, Local cultivar, Made tea quality Resource and Utilization of Taiwan Wild Tea Tree Hun-Yuan Cheng Horng-Jey Fan1,* Taiwan wild tea trees were distributed in Nantou, Chiayi, Kaohsiung, Taitung county and were located in east and west side of the central mountains at 800-1,600 meters above sea level. The relatively completed distribution areas were Dongshin Forest District Office of Mei-Yuan mountain in Nantou city, Liouguei Research Center, Taiwan Forestry Research Institute in Kaohsiung county, Nan-fong and Min-ghai mountain of Maolin district, due to mainly had set up protected areas in the early stage. In addition to distributed area, the Fanlu township, Chiayi county, Yushan forest district office, Shuei-jing and Cao mountain. -

Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia

PROTEST AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS Chiavacci, (eds) Grano & Obinger Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia East Democratic in State the and Society Civil Edited by David Chiavacci, Simona Grano, and Julia Obinger Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia Between Entanglement and Contention in Post High Growth Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia Protest and Social Movements Recent years have seen an explosion of protest movements around the world, and academic theories are racing to catch up with them. This series aims to further our understanding of the origins, dealings, decisions, and outcomes of social movements by fostering dialogue among many traditions of thought, across European nations and across continents. All theoretical perspectives are welcome. Books in the series typically combine theory with empirical research, dealing with various types of mobilization, from neighborhood groups to revolutions. We especially welcome work that synthesizes or compares different approaches to social movements, such as cultural and structural traditions, micro- and macro-social, economic and ideal, or qualitative and quantitative. Books in the series will be published in English. One goal is to encourage non- native speakers to introduce their work to Anglophone audiences. Another is to maximize accessibility: all books will be available in open access within a year after printed publication. Series Editors Jan Willem Duyvendak is professor of Sociology at the University of Amsterdam. James M. Jasper teaches at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Civil Society and the State in Democratic East Asia Between Entanglement and Contention in Post High Growth Edited by David Chiavacci, Simona Grano, and Julia Obinger Amsterdam University Press Published with the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation. -

Taiwan's 2014 Nine-In-One Election

TAIWAN’S 2014 NINE-IN-ONE ELECTION: GAUGING POLITICS, THE PARTIES, AND FUTURE LEADERS By John F. Copper* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................. 2 II. PAN-GREEN’S HANDICAPS ...................... 6 III. PAN-BLUE’S TRAVAILS ........................... 17 IV. PRE-ELECTION POLITICS ........................ 28 A. State of the Economy ............................ 28 B. Sunflower Student Movement ................... 31 C. Gas Explosion in Kaohsiung and Bad Cooking Oil Incidents ..................................... 36 V. THE CANDIDATES AND THE CAMPAIGN ..... 39 A. Taipei Mayor Race: Sean Lien v. KO Wen-je .... 44 B. Taichung Mayor Race: Jason Hu v. LIN Chia- Lung . ............................................ 48 C. Predictions of Other Elections ................... 50 D. How Different Factors May Have Influenced Voting ........................................... 50 VI. THE ELECTION RESULTS ........................ 51 A. Taipei City Mayoral Election Results ............ 53 B. Taichung Mayoral Election Results .............. 55 C. New Taipei Mayoral, Taoyuan Mayoral and Other Election Results ................................. 56 D. Main Reasons Cited Locally for the DPP Win and KMT Defeat ................................ 59 E. Reaction and Interpretation of the Election by the Media and Officialdom in Other Countries . 61 VII. CONCLUSIONS ......... ........................... 64 A. Consequences of This Election in Terms of Its Impact on Taiwan’s Future ...................... 70 * John F. Copper is the Stanley J. Buckman Professor of International Studies (emeritus) at Rhodes College in Memphis, Tennessee. He is the author of a number of books on Taiwan, including Taiwan’s Democracy on Trial in 2010, Taiwan: Nation-State or Province? Sixth edition in 2013 and The KMT Returns to Power: Elections in Taiwan 2008 to 2012 (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2013). He has written on Taiwan’s elections since 1980. (1) 2 CONTEMPORARY ASIAN STUDIES SERIES B. -

The Handy Guide for Foreigners in Taiwan

The Handy Guide for Foreigners in Taiwan Research, Development and Evaluation Commission, Executive Yuan November 2010 A Note from the Editor Following centuries of ethnic cultural assimilation and development, today Taiwan has a population of about 23 million and an unique culture that is both rich and diverse. This is the only green island lying on the Tropic of Cancer, with a plethora of natural landscapes that includes mountains, hot springs, lakes, seas, as well as a richness of biological diversity that encompasses VSHFLHVRIEXWWHUÀLHVELUGVDQGRWKHUSODQWDQGDQLPDOOLIH$TXDUWHU of these are endemic species, such as the Formosan Landlocked Salmon (櫻 花鉤吻鮭), Formosan Black Bear (台灣黑熊), Swinhoe’s Pheasant (藍腹鷴), and Black-faced Spoonbill (黑面琵鷺), making Taiwan an important base for nature conservation. In addition to its cultural and ecological riches, Taiwan also enjoys comprehensive educational, medical, and transportation systems, along with a complete national infrastructure, advanced information technology and communication networks, and an electronics industry and related subcontracting industries that are among the cutting edge in the world. Taiwan is in the process of carrying out its first major county and city reorganization since 1949. This process encompasses changes in DGPLQLVWUDWLYHDUHDV$OORIWKHVHFKDQJHVZKLFKZLOOFUHDWHFLWLHVXQGHUWKH direct administration of the central government, will take effect on Dec. 25, 7RDYRLGFDXVLQJGLI¿FXOW\IRULWVUHDGHUVWKLV+DQGERRNFRQWDLQVERWK the pre- and post-reorganization maps. City and County Reorganization Old Name New Name (from Dec. 25, 2010) Taipei County Xinbei City Taichung County, Taichung City Taichung City Tainan County, Tainan City Tainan City Kaohsiung County, Kaohsiung City Kaohsiung City Essential Facts About Taiwan $UHD 36,000 square kilometers 3RSXODWLRQ $SSUR[LPDWHO\PLOOLRQ &DSLWDO Taipei City &XUUHQF\ New Taiwan Dollar (Yuan) /NT$ 1DWLRQDO'D\ Oct. -

Taiwan Cooperative Bank, Thanks to the Use of Its Branch Network and Its Advantage As a Local Operator, Again Created Brilliant Operating Results for the Year

Stock No: 5854 TAIWAN COOPERATIVE BANK SINCE 1946 77, KUANCHIEN ROAD, TAIPEI TAIWAN TAIWAN, REPUBLIC OF CHINA COOPERATIVE TEL: +886-2-2311-8811 FAX: +886-2-2375-2954 BANK http://www.tcb-bank.com.tw WorldReginfo - bbad3649-de89-4d06-a01a-7307238a7c2b Spokesperson: Tien Lin / Kuan-Young Huang Executive Vice President / Senior Vice President & General Manager TEL : +886-2-23118811 Ext.210 / +886-2-23118811 Ext.216 E-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] WorldReginfo - bbad3649-de89-4d06-a01a-7307238a7c2b CONTENTS 02 Message to Our Shareholders 06 Financial Highlights 09 Organization Chart 10 Board of Directors & Supervisors & Executive Officers 12 Bank Profile 14 Main Business Plans for 2008 16 Market Analysis 20 Risk Management 25 Statement of Internal Control 28 Supervisors’ Report 29 Independent Auditors’ Report 31 Financial Statement 37 Designated Foreign Exchange Banks 41 Service Network WorldReginfo - bbad3649-de89-4d06-a01a-7307238a7c2b Message to Our Shareholders Message to Our Shareholders Global financial markets were characterized by relative instability in 2007 because of the impact of the continuing high level of oil prices and the subprime crisis in the United States. Figures released by Global Insight Inc. indicate that global economic performance nevertheless remained stable during the year, with the rate of economic growth reaching 3.8%--only marginally lower than the 3.9% recorded in 2006. Following its outbreak last August, the negative influence of the subprime housing loan crisis in the U.S. spread rapidly throughout the world and, despite the threat of inflation, the U.S. Federal Reserve lowered interest rates three times before the end of 2007, bringing the federal funds rate down from 5.25% to 4.25%, in an attempt to avoid a slowdown in economic growth and alleviate the credit crunch. -

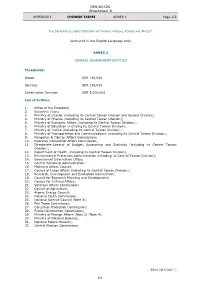

GPA/W/326 Attachment K K1

GPA/W/326 Attachment K APPENDIX I CHINESE TAIPEI ANNEX 1 Page 1/2 THE SEPARATE CUSTOMS TERRITORY OF TAIWAN, PENGHU, KINMEN AND MATSU* (Authentic in the English Language only) ANNEX 1 CENTRAL GOVERNMENT ENTITIES Thresholds: Goods SDR 130,000 Services SDR 130,000 Construction Services SDR 5,000,000 List of Entities: 1. Office of the President; 2. Executive Yuan; 3. Ministry of Interior (including its Central Taiwan Division and Second Division); 4. Ministry of Finance (including its Central Taiwan Division); 5. Ministry of Economic Affairs (including its Central Taiwan Division); 6. Ministry of Education (including its Central Taiwan Division); 7. Ministry of Justice (including its Central Taiwan Division); 8. Ministry of Transportation and Communications (including its Central Taiwan Division); 9. Mongolian & Tibetan Affairs Commission; 10. Overseas Compatriot Affairs Commission; 11. Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (including its Central Taiwan Division); 12. Department of Health (including its Central Taiwan Division); 13. Environmental Protection Administration (including its Central Taiwan Division); 14. Government Information Office; 15. Central Personnel Administration; 16. Mainland Affairs Council; 17. Council of Labor Affairs (including its Central Taiwan Division); 18. Research, Development and Evaluation Commission; 19. Council for Economic Planning and Development; 20. Council for Cultural Affairs; 21. Veterans Affairs Commission; 22. Council of Agriculture; 23. Atomic Energy Council; 24. National Youth Commission; 25. National Science Council (Note 3); 26. Fair Trade Commission; 27. Consumer Protection Commission; 28. Public Construction Commission; 29. Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Note 2) (Note 4); 30. Ministry of National Defense; 31. National Palace Museum; 32. Central Election Commission. … 2014 (WT/Let/…) K1 GPA/W/326 Attachment K APPENDIX I CHINESE TAIPEI ANNEX 1 Page 2/2 * In English only. -

Directory of Head Office and Branches

Directory of Head Office and Branches 106 I. Domestic Business Units 120 Sec 1, Chongcing South Road, Jhongjheng District, Taipei City 10007, Taiwan (R.O.C.) P.O. Box 5 or 305 SWIFT: BKTWTWTP http://www.bot.com.tw TELEX 11201 TAIWANBK CODE OFFICE ADDRESS TELEPHONE FAX 0037 Department of 120 Sec 1, Chongcing South Road, Jhongjheng District, 02-23493399 02-23759708 Business ( I ) Taipei City 0059 Department of 120 Sec 1, Gueiyang Street, Jhongjheng District, 02-23615421 02-23751125 Public Treasury Taipei City 0071 Department of 49 Guancian Road, Jhongjheng District, Taipei City 02-23812949 02-23753800 Business ( II ) 0082 Department of 58 Sec 1, Chongcing South Road, Jhongjheng District, 02-23618030 02-23821846 Trusts Taipei City 0691 Offshore Banking 1F, 3 Baocing Road, Jhongjheng District, Taipei City 02-23493456 02-23894500 Branch 1850 Department of 4F, 120 Sec 1, Gueiyang Street, Jhongjheng District, 02-23494567 02-23893999 Electronic Banking Taipei City 1698 Department of 2F, 58 Sec 1, Chongcing South Road, Jhongjheng 02-23882188 02-23716159 Securities District, Taipei City 0093 Tainan Branch 155 Sec 1, Fucian Road, Central District, Tainan City 06-2160168 06-2160188 0107 Taichung Branch 140 Sec 1, Zihyou Road, West District, Taichung City 04-22224001 04-22224274 0118 Kaohsiung Branch 264 Jhongjheng 4th Road, Cianjin District, 07-2515131 07-2211257 Kaohsiung City 0129 Keelung Branch 16, YiYi Road, Jhongjheng District, Keelung City 02-24247113 02-24220436 0130 Chunghsin New 11 Guanghua Road, Jhongsing Village, Nantou City, 049-2332101 -

An Assessment of Water Resources in the Taiwan Strait Island Using the Water Poverty Index

sustainability Article An Assessment of Water Resources in the Taiwan Strait Island Using the Water Poverty Index Tung-Tsan Chen 1,*, Wei-Ling Hsu 2,* and Wen-Kuang Chen 1 1 Department of Civil Engineering and Engineering Management, National Quemoy University, Kinmen County 89250, Taiwan; [email protected] 2 School of Urban and Environmental Science, Huaiyin Normal University, Huai’an 223300, Jiangsu, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (T.-T.C.); [email protected] (W.-L.H.); Tel.: +886-931445596 (T.-T.C.); +86-15751385380 (W.-L.H.) Received: 31 January 2020; Accepted: 14 March 2020; Published: 17 March 2020 Abstract: Water resources are a very important issue in the Global Risk 2015 published by the World Economic Forum. The research objective of this study was to construct a Water Poverty Index (WPI) for islands. The empirical scope of this study was based on Kinmen Island in the Taiwan Strait, which has very scarce water resources. Kinmen has a dry climate with low rainfall and high evaporation. Therefore, the Kinmen area is long-term dependent on groundwater resources and faces serious water resource problems. This study used the WPI to examine various issues related to water resources. In addition, this study selected several main indicators and performed time series calculations to examine the future trends of water resources in Kinmen. The results show that the overall water resources of Kinmen are scarce. To ensure sustainable development of water resources in Kinmen, policies to improve water scarcity, such as water resource development, water storage improvement, and groundwater control, should be researched. -

Merger and Takeover Attempts in Taiwanese Party Politics

This is the author’s accepted version of a forthcoming article in Issues and Studies that will be published by National ChengChi University: http://issues.nccu.edu.tw/ Accepted version downloaded from SOAS Research Online: http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/24849/ Merger and Takeover Attempts in Taiwanese Party Politics Dafydd Fell, Department of Politics and International Studies, SOAS University of London Introduction It is often assumed that in mature democracies party mergers are rare. Mair’s study of Western European parties found only 18 cases between 1945 and 1987, with almost half of them taking place in just two countries, Italy and Finland.1 Since the Second World War the only merger of relevant political parties in the United Kingdom was between the Social Democratic Party and Liberal Party in 1988. Unsurprisingly the literature on party merging was until recently quite limited. However, party mergers in consolidated democracies such as in Canada, the Netherlands and Germany in the post Cold War period has led to a renewed interest in the phenomenon.2 In fact a recent study that found 94 European party 3 merger cases in the post-war period suggests mergers are becoming more common. Party mergers are more frequent in new democracies where the party system is not yet fully institutionalised. Since the early 1990s the South Korean party system has featured a seemingly endless pattern of party splits and mergers.4 In another Asian democracy, Japan, party mergers have played a critical role in the development of its party system. For instance, after a period of extensive party splinters and new party start-ups, a major party merger between 1997 and 1998 allowed the Democratic Party of Japan to become a viable 5 challenger to the Liberal Democratic Party for government. -

Taking Kaohsiung City Green Building Autonomy Act for Example

ISBN: 978-84-697-1815-5 An Exploration of Law Instruments in Kaohsiung Sustainable Actions: Taking Kaohsiung City Green Building Autonomy Act for example Speakers: Tseng, Pin-Chieh1; Huang, Chin-Ming2; Chou, I-Shin3; Hsieh, Chih-Chang4 1 Kaohsiung City Government, Kaohsiung, Taiwan 2 Kaohsiung City Government, Kaohsiung, Taiwan 3 Kaohsiung City Government, Kaohsiung, Taiwan 4 Kaohsiung City Government, Kaohsiung, Taiwan Abstract: After Kaohsiung City merging with surrounding Kaohsiung County and thus expanding in scale in 2010, Kaohsiung city has the characteristics of multi-ethnic, diverse landscape, and distinctive cultures. The promotion of the action plan for Kaohsiung building environment transformation is based on the planning of the residential and commercial sector. A periodical approach was used for plan promotion according to various topographical and cultural environments, stressing local culture, green buildings, and citizen participation. Relevant laws were established to ensure the practical implementation of the transformation plan. This plan enables a reconsideration of cultural positioning and corrects the development of built environments. By adopting a core positioning of water and greenery, the concepts of ecology, economy, livability, creativity, and internationality are used to remold the living environment of Greater Kaohsiung. Thus, along with the citizens of Kaohsiung City, we participated in the action plan for sustainable building environment transformation. "Kaohsiung City Green Building Autonomy Act" is the National Capital Act to make the green building standard higher than the central ones. By stipulating the green building design of equipment and facilities, the act laid the technique foundation of environment control for the meaning of Kaohsiung citizen’s green life. -

Timrex Booklet

NCAR/ EOL Project Information For TIMREX Terrain-influenced Monsoon Rainfall Experiment Field Program – 15 May to 30 June 2008 Field work – 15 April to 15 July 2008 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PROJECT INFORMATION ...................................................................................................................... 4 PROJECT OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................................... 4 PROJECT GOAL............................................................................................................................................ 4 PROJECT SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... 4 GENERAL INFORMATION...................................................................................................................... 5 COUNTRY OVERVIEW.................................................................................................................................. 5 CLIMATE ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 MAP ............................................................................................................................................................ 5 LANGUAGE.................................................................................................................................................. 6 Interpreters............................................................................................................................................