Mount Kenya National Park CHALLENGES in PROTECTION and MANAGEMENT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pending World Record Waterbuck Wins Top Honor SC Life Member Susan Stout Has in THIS ISSUE Dbeen Awarded the President’S Cup Letter from the President

DSC NEWSLETTER VOLUME 32,Camp ISSUE 5 TalkJUNE 2019 Pending World Record Waterbuck Wins Top Honor SC Life Member Susan Stout has IN THIS ISSUE Dbeen awarded the President’s Cup Letter from the President .....................1 for her pending world record East African DSC Foundation .....................................2 Defassa Waterbuck. Awards Night Results ...........................4 DSC’s April Monthly Meeting brings Industry News ........................................8 members together to celebrate the annual Chapter News .........................................9 Trophy and Photo Award presentation. Capstick Award ....................................10 This year, there were over 150 entries for Dove Hunt ..............................................12 the Trophy Awards, spanning 22 countries Obituary ..................................................14 and almost 100 different species. Membership Drive ...............................14 As photos of all the entries played Kid Fish ....................................................16 during cocktail hour, the room was Wine Pairing Dinner ............................16 abuzz with stories of all the incredible Traveler’s Advisory ..............................17 adventures experienced – ibex in Spain, Hotel Block for Heritage ....................19 scenic helicopter rides over the Northwest Big Bore Shoot .....................................20 Territories, puku in Zambia. CIC International Conference ..........22 In determining the winners, the judges DSC Publications Update -

The Eastern Cape –

The Eastern Cape – Revisited By Jeff Belongia A return to South Africa’s Eastern Cape was inevitable – the idea already firmly planted in my mind since my first visit in 1985. Africa, in general, has a wonderful yet strange control over the soul, and many writers have tried to express the reasoning behind it. I note this captivation and recognize the allure, and am too weak to resist. For me, Africa is what dreams are made of – and I dream of it daily. Dr. Martin Luther King was wise when he chose the phrase, “I have a dream.” He could have said, “I have a strategic plan.” Not quite the same effect! People follow their dreams. As parents we should spend more time teaching our children to dream, and to dream big. There is no Standard Operating Procedure to get through the tough times in life. Strength and discipline are measured by the depth and breadth of our dreams and not by strategic planning! The Catholic nuns at Saint Peter’s grade school first noted my talents. And they all told me to stop daydreaming. But I’ve never been able to totally conquer that urge – I dream continually of the romance of Africa, including the Eastern Cape. The Eastern Cape is a special place with a wide variety of antelope – especially those ‘pygmy’ species found nowhere else on the continent: Cape grysbok, blue duiker, Vaal rhebok, steenbok, grey duiker, suni, and oribi. Still not impressed? Add Cape bushbuck, mountain reedbuck, blesbok, nyala, bontebok, three colour phases of the Cape springbok, and great hunting for small cats such as caracal and serval. -

Wildlife and Wild Places in Mozambique K

Wildlife and Wild Places in Mozambique K. L Tinley, A. J. Rosinha, Jose L. P. Lobao Tello and T. P. Dutton This account of the national parks, reserves and other places worthy of pro- tection in Mozambique gives some idea of the wealth of wildlife in this newly independent country. One special reserve has 25,000 buffaloes—the largest concentration in the world. Protected conservation areas in Mozambique fall into six categories: 1. Parques nacionais - national parks; 2. Reservas especiais - special game reserves; 3. Reservas parciais - partial reserves; 4. Regimen de vigilancia - fauna protection zones; 5. Coutadas - hunting and photographic safari areas, normally run on a private concession basis; 6. Reservas florestais - forest reserves. Some unique areas are still outside this system but have been recommended for inclusion, together with other ecosystems worthy of inclusion in the future. Game farming or ranching is attracting considerable interest; one private and one government scheme have been proposed. NATIONAL PARKS 1.* Parque Nacional da Gorongosa (c. 3770 sq km). Situated at the southern limit of the great rift valley with an extensive flood plain and associated lakes, this park includes Brachystegia woodland Acacia and Combretum savanna. Sharply rising inselbergs (volcanic protrusions) are also a feature. The ungulates are typical floodplain species, including elephant (abundant), buffalo, wildebeest, waterbuck, zebra, reedbuck, impala and oribi; on the elevated woodland and savanna habitat there are black rhino, eland, Lichten- stein's hartebeest, sable, kudu, nyala, Sharpe's grysbok, suni, blue and grey duiker, and klipspringer are common on rock outcrops; lion, leopard and hippopotamus are abundant. Both land and water birds are prolific and diverse, and crocodiles are very common. -

Caracal Feeding Behaviour

Series: 2_003/2 less than 25% of the diet, less than 15% in the Karoo, Sandveld and Bedford area, FEEDING ECOLOGY OF THE 10% in the southern Free State, and less CARACAL than 7% in Namaqualand. A study in Namibia found that less than 12% of the Although the caracal is an opportunistic caracals that were tracked with radio predator like the black-backed jackal, it collars predated on livestock, and in these feeds mostly on small- to medium-sized cases, livestock made up only 2% of those mammals. caracals’ diets • Caracals do scavenge at times, especially Diet when resources are low. In areas where • Over 90% of the diet consists of mammals. caracals are persecuted, however, Rodents (e.g. rats, mice and springhare), caracals are rarely observed to return to a rabbits and hares, and rock hyrax (dassie) kill. are the most common prey items in caracal diet. In areas where small- and The occurrence of specific prey items in the medium-sized antelope are abundant, they diet fluctuates seasonally, which means that also form a major part of the diet caracals eat the most abundant prey • Birds constitute a small percentage of the available at the time. diet (generally less than 5% of the diet). The diet of caracals does not differ much between protected areas (such as game • Reptiles are only eaten occasionally (less reserves) and farmland if the same types of than 1% of the diet). prey are available on farms as in the • Other carnivores (smaller species) are neighbouring protected area. preyed on opportunistically. In Namibia, the most common carnivore species found Feeding behaviour in caracal diet were black-backed jackal Caracals hunt daily and are capable of and African wild cat. -

Animals of Africa

Silver 49 Bronze 26 Gold 59 Copper 17 Animals of Africa _______________________________________________Diamond 80 PYGMY ANTELOPES Klipspringer Common oribi Haggard oribi Gold 59 Bronze 26 Silver 49 Copper 17 Bronze 26 Silver 49 Gold 61 Copper 17 Diamond 80 Diamond 80 Steenbok 1 234 5 _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ Cape grysbok BIG CATS LECHWE, KOB, PUKU Sharpe grysbok African lion 1 2 2 2 Common lechwe Livingstone suni African leopard***** Kafue Flats lechwe East African suni African cheetah***** _______________________________________________ Red lechwe Royal antelope SMALL CATS & AFRICAN CIVET Black lechwe Bates pygmy antelope Serval Nile lechwe 1 1 2 2 4 _______________________________________________ Caracal 2 White-eared kob DIK-DIKS African wild cat Uganda kob Salt dik-dik African golden cat CentralAfrican kob Harar dik-dik 1 2 2 African civet _______________________________________________ Western kob (Buffon) Guenther dik-dik HYENAS Puku Kirk dik-dik Spotted hyena 1 1 1 _______________________________________________ Damara dik-dik REEDBUCKS & RHEBOK Brown hyena Phillips dik-dik Common reedbuck _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________African striped hyena Eastern bohor reedbuck BUSH DUIKERS THICK-SKINNED GAME Abyssinian bohor reedbuck Southern bush duiker _______________________________________________African elephant 1 1 1 Sudan bohor reedbuck Angolan bush duiker (closed) 1 122 2 Black rhinoceros** *** Nigerian -

A Scoping Review of Viral Diseases in African Ungulates

veterinary sciences Review A Scoping Review of Viral Diseases in African Ungulates Hendrik Swanepoel 1,2, Jan Crafford 1 and Melvyn Quan 1,* 1 Vectors and Vector-Borne Diseases Research Programme, Department of Veterinary Tropical Disease, Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0110, South Africa; [email protected] (H.S.); [email protected] (J.C.) 2 Department of Biomedical Sciences, Institute of Tropical Medicine, 2000 Antwerp, Belgium * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +27-12-529-8142 Abstract: (1) Background: Viral diseases are important as they can cause significant clinical disease in both wild and domestic animals, as well as in humans. They also make up a large proportion of emerging infectious diseases. (2) Methods: A scoping review of peer-reviewed publications was performed and based on the guidelines set out in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews. (3) Results: The final set of publications consisted of 145 publications. Thirty-two viruses were identified in the publications and 50 African ungulates were reported/diagnosed with viral infections. Eighteen countries had viruses diagnosed in wild ungulates reported in the literature. (4) Conclusions: A comprehensive review identified several areas where little information was available and recommendations were made. It is recommended that governments and research institutions offer more funding to investigate and report viral diseases of greater clinical and zoonotic significance. A further recommendation is for appropriate One Health approaches to be adopted for investigating, controlling, managing and preventing diseases. Diseases which may threaten the conservation of certain wildlife species also require focused attention. -

Samburu National Reserve Lake Nakuru National Park

EAST AFRICAN BIRDING EAST AFRICAN BIRDING Herds of zebras and wildebeest grazing endless grasslands studded with flat- Samburu NR Shaba NR SOMALIA topped acacia trees, dramatic volcanic UGANDA Buffalo Springs NR calderas brimming with big game and Kakamega Forest predators, red-robed Maasai herding Mt Kenya NP eastern Mt Kenya skinny cattle – these are well-known images of quintessential Africa, and Lake Victoria Lake Nakuru NP they can all be discovered in Kenya and KENYA Tanzania. Less well known is that each Nairobi Masai Mara NR country hosts more than 1 000 bird species. This diversity, combined with a superb network of protected areas, ex- Serengeti NP PROMISE Amboseli NR cellent lodges and friendly people, prompts Adam Riley to recommend them as top birding destinations. Although there are many excellent locations within each nation – think Masai Mara, Amboseli and Kakamega in Kenya and Ngorongoro Mt Kilimanjaro Crater Selous, the Eastern Arc Mountains and Zanzibar in Tanzania – he describes here just six that shouldn’t be missed. • Arusha They can all be visited in one two-week trip, starting in Nairobi and ending in Arusha. Any time of year is good, even TANZANIA the April–May rainy season when the scenery is lush and there is less dust, and when there are fewer tourists and • Mombasa N Tarangire NP rates are lower. Expect to net about 450 bird and more than 50 mammal species on an adventure to these parks. U TEXT & PHOTOGRAPHS BY ADAM RILEY INDIAN 200 km OCEAN The arid, acacia-studded savanna of Samburu, Shaba and Buffalo Springs national reserves are SAMBURU NATIONAL interspersed with rugged hill ranges. -

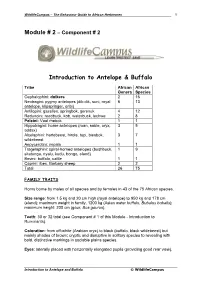

Introduction to Antelope & Buffalo

WildlifeCampus – The Behaviour Guide to African Herbivores 1 Module # 2 – Component # 2 Introduction to Antelope & Buffalo Tribe African African Genera Species Cephalophini: duikers 2 16 Neotragini: pygmy antelopes (dik-dik, suni, royal 6 13 antelope, klipspringer, oribi) Antilopini: gazelles, springbok, gerenuk 4 12 Reduncini: reedbuck, kob, waterbuck, lechwe 2 8 Peleini: Vaal rhebok 1 1 Hippotragini: horse antelopes (roan, sable, oryx, 3 5 addax) Alcelaphini: hartebeest, hirola, topi, biesbok, 3 7 wildebeest Aepycerotini: impala 1 1 Tragelaphini: spiral-horned antelopes (bushbuck, 1 9 sitatunga, nyalu, kudu, bongo, eland) Bovini: buffalo, cattle 1 1 Caprini: ibex, Barbary sheep 2 2 Total 26 75 FAMILY TRAITS Horns borne by males of all species and by females in 43 of the 75 African species. Size range: from 1.5 kg and 20 cm high (royal antelope) to 950 kg and 178 cm (eland); maximum weight in family, 1200 kg (Asian water buffalo, Bubalus bubalis); maximum height: 200 cm (gaur, Bos gaurus). Teeth: 30 or 32 total (see Component # 1 of this Module - Introduction to Ruminants). Coloration: from off-white (Arabian oryx) to black (buffalo, black wildebeest) but mainly shades of brown; cryptic and disruptive in solitary species to revealing with bold, distinctive markings in sociable plains species. Eyes: laterally placed with horizontally elongated pupils (providing good rear view). Introduction to Antelope and Buffalo © WildlifeCampus WildlifeCampus – The Behaviour Guide to African Herbivores 2 Scent glands: developed (at least in males) in most species, diffuse or absent in a few (kob, waterbuck, bovines). Mammae: 1 or 2 pairs. Horns. True horns consist of an outer sheath composed mainly of keratin over a bony core of the same shape which grows from the frontal bones. -

The Social and Spatial Organisation of the Beira Antelope (): a Relic from the Past? Nina Giotto, Jean-François Gérard

The social and spatial organisation of the beira antelope (): a relic from the past? Nina Giotto, Jean-François Gérard To cite this version: Nina Giotto, Jean-François Gérard. The social and spatial organisation of the beira antelope (): a relic from the past?. European Journal of Wildlife Research, Springer Verlag, 2009, 56 (4), pp.481-491. 10.1007/s10344-009-0326-8. hal-00535255 HAL Id: hal-00535255 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00535255 Submitted on 11 Nov 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Eur J Wildl Res (2010) 56:481–491 DOI 10.1007/s10344-009-0326-8 ORIGINAL PAPER The social and spatial organisation of the beira antelope (Dorcatragus megalotis): a relic from the past? Nina Giotto & Jean-François Gerard Received: 16 March 2009 /Revised: 1 September 2009 /Accepted: 17 September 2009 /Published online: 29 October 2009 # Springer-Verlag 2009 Abstract We studied the social and spatial organisation of Keywords Dwarf antelope . Group dynamics . Grouping the beira (Dorcatragus megalotis) in arid low mountains in pattern . Phylogeny. Territory the South of the Republic of Djibouti. Beira was found to live in socio-spatial units whose ranges were almost non- overlapping, with a surface area of about 0.7 km2. -

Africa Maximum Safaris Specials 2020

AFRICA MAXIMUM SAFARIS SPECIALS 2020 South Africa North West Province Experience South Africa Package For the first time hunter to Africa we have the best package at the best price. Come experience the South African rich wildlife on a hunting safari with Africa Maximum Safaris. This is an 8-day hunt. 6 hunting days and arrival and departure day. Daily rate for 1 hunter: Cost $1600.00 Species included: Blue/Black Wildebeest or Zebra $1200 Impala $450 Springbuck $500 $450 Blesbuck Total cost $ 4200 Classic South Africa Plaines game safari 10-Day safari: 10 hunting days and arrival and departure day. Daily rates for 1 hunter and 1 observer included. Cost $ 2000.00. Species included: Kudu under 55 $2900 Gemsbuck $1,500 Blue or Black Wildebeest $1200 Impala or Blesbuck $450 Springbuck $500 Total cost $ 8550 Premier South African plainesgame safari 12 Day safaris: 10 hunting days and arrival and departure day. Daily rate for 1 hunter and 1 observer included. Cost $ 2200.00. Species Included: Greater Kudu under 55 $2,900 Cape Eland $2,900 Nyala $2,600 Kalahari Gemsbuck $1,500 Burchell Zebra $1200 Southern Impala $450 South Africa Springbuck $500 Total cost $ 14250.00 Super saver safari package 2019 Come experience a safari in South Africa at a very affordable rate. 7 Day safaris for 1 hunter and 1 observer; includes 5 hunting days and arrival and departure days. Species included in the package: Impala, Blesbuck and Blue Wildebeest. Terms and conditions: availability limited to certain months, no exchange of species or days from this package, Limited availability of packages. -

Aspects of the Conservation of Oribi (Ourebia Ourebi) in Kwazulu-Natal

Aspects ofthe conservation oforibi (Ourebia ourebi) in KwaZulu-Natal Rebecca Victoria Grey Submitted in partial fulfilment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master ofScience In the School ofBiological and Conservation Sciences At the University ofKwaZulu-Natal Pietermaritzburg November 2006 Abstract The oribi Ourebia ourebi is probably South Africa's most endangered antelope. As a specialist grazer, it is extremely susceptible to habitat loss and the transformation of habitat by development. Another major threat to this species is illegal hunting. Although protected and listed as an endangered species in South Africa, illegal poaching is widespread and a major contributor to decreasing oribi populations. This study investigated methods of increasing oribi populations by using translocations and reintroductions to boost oribi numbers and by addressing over hunting. Captive breeding has been used as a conservation tool as a useful way of keeping individuals of a species in captivity as a backup for declining wild populations. In addition, most captive breeding programmes are aimed at eventually being able to reintroduce certain captive-bred individuals back into the wild to supplement wild populations. This can be a very costly exercise and often results in failure. However, captive breeding is a good way to educate the public and create awareness for the species and its threats. Captive breeding of oribi has only been attempted a few times in South Africa, with varied results. A private breeding programme in Wartburg, KwaZulu-Natal was quite successful with the breeding of oribi. A reintroduction programme for these captive-bred oribi was monitored using radio telemetry to assess the efficacy ofsuch a programme for the oribi. -

The Distribution of Some Large Mammals in Kenya Staff, White Hunters, Foresters, Agricultural and Veterinary Officers, Farmers and Many Others

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The publication of this paper would not have been possible without the generous support of the following: The International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. The World Wildlife Fund. Monsieur Charles Vander Elst. J.E.Afr.Nat.Hist.Soc. Vol.XXIV No.3 (107) June 1963 Introduction Detailed distribution maps of wild animals play a useful part in the study of the ecology and status of the species concerned, and form a basis for comparison in future years. They are also a valu• able aid to the sound planning of conservation and exploitation measures affecting wild life. The distribution maps of large mammals presented in this paper have been prepared as part of the programme of the Fauna Research Unit of the Kenya Game Department. They refer only to the distribution of the species within Kenya, although it would be desirable when possible to extend the work beyond this biologically meaningless boundary. We have dealt only with the pachyderms and the larger carnivores and antelopes; we have omitted some of the smaller members of the last two groups because we have as yet been unable to obtain sufficiently detailed informa• tion about their distribution. A complete list of the larger Carnivora (i.e. excluding the Mustelidae and Viverridae), the Proboscidea, Perissodactyla and Artiodactyla occurring in Kenya appears at the end of this paper. Those species appearing in brackets have not been dealt with in this paper. The distribution maps are accompanied by four others showing:• (2)(1) altitude;physical features,(3) rainfall;place names,and (4)andvegetation.conservationTheseareas;are drawn from maps in the Atlas of Kenya (1959), with the gratefully acknowledged permission of the Director of Surveys, Kenya.