Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reshaping a Tradition. Founding the Habsburg-Lorraine Dynastic State in the 18Th Century

Исторические исследования www.historystudies.msu.ru _____________________________________________________________________________ Лебо К. Reshaping a tradition. Founding the Habsburg-Lorraine dynastic state in the 18th century Аннотация: В статье исследуются компоненты власти в композитарной монархии Габсбургов и конструирование политической легитимности посредством управленческих практик, сочинений, речей и изображений. Монархия Габсбургов в XVIII в. не представляла собой однородного целого, объединяя территории с различной степенью интеграции. Выборность корон и их переходы от одной ветви рода к другой создавали сложную ситуацию, в которой Габсбургам удавалось утвердить свое господство, сочетая следование традиции и изменения. Административные реформы поддерживались символическим дискурсом. Династический дискурс пришел на смену истории правящего дома и стал способом утвердить принцип государственного интереса. Власть династии была основана на доминировании над территорией. Новые вертикальные связи исходили от Марии Терезии, распространяя ее господство за пределы владений Австрийского дома. На своих более чем двухстах портретах Мария Терезия всегда изображалась с регалиями, вид которых варьировался в зависимости от места, где картина должна была находиться, с тем, чтобы подчеркнуть своеобразие каждой территории и единство монархии, связь между правителем и подвластной территорией. Ключевые слова: династическое государство, дом Габсбургов, империя, институциональные реформы, композитарная монархия, наследственная монархия, символический -

Diplomatic Note to the Decleration of Sovereignty

REM PUBLICAM DECLARARE MEMORANDUM DILPOMATICAE October 2013 via Babenberg Diplomatic of Dynasty Babenberg Diplomatic Service a Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Government of the Sovereign Dynasty of Babenberg ratified by the CarlsRat WeisenRat published by the Department of Sovereignty Representation for the sovereigns Dynasty Babenberg The patriarch of Dynasty The General Ambassador of the Sovereign Dynasty Structure 1. History, Dynasty, Activities I. Remarks to archive II. Extrapolation to the Department of customary international law 2. Explicit the diplomatic note on the declaration 3. Legal situation results in I. Originary non-state subject of international law from customary international law including clause to declarative extension to originary subject of international law II. Establishment and extension of already existing diplomatic relations 4. Lex Vita Babenberg & Confederation of United Constitutions and Laws 5. Future orientation I. Actions and the duty of the Babenberg Dynasty, their value, experience, wisdom, knowledge, the well-being of the earth and humanity– People’s empathy II. Operations; Diplomacy, Peace Foundation, Peace maintenance, Peace keeping; Education; Family – children – youth; including foundations and companies of the Babenberg Dynasty III. Cultural maintenance and or restoration IV. International cooperation 6. Financial affairs of the Sovereign Babenberg Dynasty I. Financial concept/s, subsidy/s, donation/s, use of funds 7. Concluding information I. Documents and references II. Closing words 2 | S e i t e 1. History, Dynasty, Activities The Babenberg family has had a wide variety of names which have already been used in the past, as well as today. With the first document from the year AD 414, the roots of the entire family arise, internal records leading up to the year 69 BC. -

The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume IV - C

Cambridge University Press 0521414113 - The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume IV - c. 1024-c. 1198 Edited by David Luscombe and Jonathan Riley-Smith Index More information INDEX Aachen, 77, 396, 401, 402, 404, 405 Abul-Barakat al-Jarjara, 695, 700 Aaron, bishop of Cologne, 280 Acerra, counts of, 473 ‘Abbadids, kingdom of Seville, 157 Acre ‘Abbas ibn Tamim, 718 11th century, 702, 704, 705 ‘Abbasids 12th century Baghdad, 675, 685, 686, 687, 689, 702 1104 Latin conquest, 647 break-up of empire, 678, 680 1191 siege, 522, 663 and Byzantium, 696 and Ayyubids, 749 caliphate, before First Crusade, 1 fall to crusaders, 708 dynasty, 675, 677 fall to Saladin, 662, 663 response to Fatimid empire, 685–9 Fatimids, 728 abbeys, see monasteries and kingdom of Jerusalem, 654, 662, 664, abbots, 13, 530 667, 668, 669 ‘Abd Allah al-Ziri, king of Granada, 156, 169–70, Pisans, 664 180, 181, 183 trade, 727 ‘Abd al-Majid, 715 13th century, 749 ‘Abd al-Malik al-Muzaffar, 155, 158, 160, 163, 165 Adalasia of Sicily, 648 ‘Abd al-Mu’min, 487 Adalbero, bishop of Wurzburg,¨ 57 ‘Abd al-Rahman (Shanjul), 155, 156 Adalbero of Laon, 146, 151 ‘Abd al-Rahman III, 156, 159 Adalbert, archbishop of Mainz, 70, 71, 384–5, ‘Abd al-Rahman ibn Ilyas, 682 388, 400, 413, 414 Abelard of Conversano, 109, 110, 111, 115 Adalbert, bishop of Prague, 277, 279, 284, 288, Aberconwy, 599 312 Aberdeen, 590 Adalbert, bishop of Wolin, 283 Abergavenny, 205 Adalbert, king of Italy, 135 Abernethy agreement, 205 Adalgar, chancellor, 77 Aberteifi, 600 Adam of Bremen, 295 Abingdon, 201, 558 Adam of -

Meissen Masterpieces Exquisite and Rare Porcelain Models from the Royal House of Saxony to Be Offered at Christie’S London

For Immediate Release 30 October 2006 Contact: Christina Freyberg +44 20 7 752 3120 [email protected] Alexandra Kindermann +44 20 7 389 2289 [email protected] MEISSEN MASTERPIECES EXQUISITE AND RARE PORCELAIN MODELS FROM THE ROYAL HOUSE OF SAXONY TO BE OFFERED AT CHRISTIE’S LONDON British and Continental Ceramics Christie’s King Street Monday, 18 December 2006 London – A collection of four 18th century Meissen porcelain masterpieces are to be offered for sale in London on 18 December 2006 in the British and Continental Ceramics sale. This outstanding Meissen collection includes two white porcelain models of a lion and lioness (estimate: £3,000,000-5,000,000) and a white model of a fox and hen (estimate: £200,000-300,000) commissioned for the Japanese Palace in Dresden together with a white element vase in the form of a ewer (£10,000-15,000). “The porcelain menagerie was an ambitious and unparalleled project in the history of ceramics and the magnificent size of these models is a testament to the skill of the Meissen factory,” said Rodney Woolley, Director and Head of European Ceramics. “The sheer exuberance of these examples bears witness to the outstanding modelling of Kirchner and Kändler. The opportunity to acquire these Meissen masterpieces from the direct descendants of Augustus the Strong is unique and we are thrilled to have been entrusted with their sale,” he continued. The works of art have been recently restituted to the heirs of the Royal House of Saxony, the Wettin family. Commenting on the Meissen masterpieces, a spokesperson for the Royal House of Saxony said: “The Wettin family has worked closely, and over many years with the authorities to achieve a successful outcome of the restitution of many works of art among which are these four Meissen porcelain objects, commissioned by our forebear Augustus the Strong. -

Art & History of Vienna

Art & History of Vienna Satoko Friedl Outline History Architecture Museums Music Eat & Drink Satoko Friedl: Art & History of Vienna 26 September 2011 2 History Architecture Museums Music Eat & Drink Satoko Friedl: Art & History of Vienna 26 September 2011 3 "It all started with a big bang…" Satoko Friedl: Art & History of Vienna 26 September 2011 4 Prehistoric Vienna . Sporadic archeological finds from Paleolithic age . Evidence of continuous settlements from Neolithic age (~5000 BC) Venus of Willendorf (~25000 BC, Naturhistorisches Museum) Satoko Friedl: Art & History of Vienna 26 September 2011 5 Vindobona: The Roman Fortress . Founded ~20 AD (after today‘s Austria was conquered) . "Standard" layout Roman military camp (castrum) surrounded by civilian city . Several excavation sites and archeological finds Reconstruction of Vindobona Satoko Friedl: Art & History of Vienna 26 September 2011 6 Roman Excavations in Vienna (1) Roman floor heating (Excavations in Römermuseum, Hoher Markt) Roman stones from the thermae (Sterngasse/Herzlstiege) Satoko Friedl: Art & History of Vienna 26 September 2011 7 Roman Excavations in Vienna (2) Roman and medieval houses (Michaelerplatz) Satoko Friedl: Art & History of Vienna 26 September 2011 8 Location of the Roman Fortress (1) . Upper edge was washed away by a flood in 3rd century Satoko Friedl: Art & History of Vienna 26 September 2011 9 Location of the Roman Fortress (2) Street called "Tiefer Danube Graben" canal (deep moat) Rotenturm- strasse Place called "Graben" (moat) St. Stephen‘s Cathedral Tiefer Graben(modern city center) Satoko Friedl: Art & History of Vienna 26 September 2011 10 Old Friends… Is it worth the long travel? Obelix, shall we go to Vindobona? Satoko Friedl: Art & History of Vienna 26 September 2011 11 The Dark Ages . -

The Daughter of a Byzantine Emperor – the Wife of a GalicianVolhynian Prince

The daughter of a Byzantine Emperor – the wife of a GalicianVolhynian Prince «The daughter of a Byzantine Emperor – the wife of a GalicianVolhynian Prince» by Alexander V. Maiorov Source: Byzantinoslavica Revue internationale des Etudes Byzantines (Byzantinoslavica Revue internationale des Etudes Byzantines), issue: 12 / 2014, pages: 188233, on www.ceeol.com. The daughter of a Byzantine Emperor – the wife of a Galician-Volhynian Prince Alexander V. MAIOROV (Saint Petersburg) The Byzantine origin of Prince Roman’s second wife There is much literature on the subject of the second marriage of Roman Mstislavich owing to the disagreements between historians con- cerning the origin of the Princeís new wife. According to some she bore the name Anna or, according to others, that of Maria.1 The Russian chronicles give no clues in this respect. Indeed, a Galician chronicler takes pains to avoid calling the Princess by name, preferring to call her by her hus- band’s name – “âĺëčęŕ˙ ęí˙ăčí˙ Ðîěŕíîâŕ” (Roman’s Grand Princess).2 Although supported by the research of a number of recent investiga- tors, the hypothesis that she belonged to a Volhynian boyar family is not convincing. Their arguments generally conclude with the observation that by the early thirteenth century there were no more princes in Rusí to whom it would have been politically beneficial for Roman to be related.3 Even less convincing, in our opinion, is a recently expressed supposition that Romanís second wife was a woman of low birth and was not the princeís lawful wife at all.4 Alongside this, the theory of the Byzantine ori- gin of Romanís second wife has been significantly developed in the litera- ture on the subject. -

Module Hi1200 Europe, 1000-1250

MODULE HI1200 EUROPE, 1000-1250: WAR, GOVERNMENT AND SOCIETY IN THE AGE OF THE CRUSADES Michaelmas Term Professor Robinson ( 10 ECTS ) CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2 2. A Guide to Module HI1200 3 3. Lecture Topics 6 4. Essay Titles 6 5. Reading List 8 6. Tutorial Assignments 11 1 1. INTRODUCTION This module deals with social and political change in Europe during the two-and-a- half centuries of the development of the crusading movement. It focuses in particular on the internal development of France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Byzantium (the Eastern Christian empire based on Constantinople) and the crusading colonies in the Near East. The most important themes are the development of royal and imperial authority, the structure of aristocratic society, rebellion and the threat of political disintegration, warfare as a primary function of the secular ruling class and the impact of war on the development of European institutions. Module HI1200 is available as an option to Single Honors, Two-Subject Moderatorship and History and Political Science Junior Freshman students. This module is a compulsory element of the Junior Freshman course in Ancient and Medieval History and Culture. The module may also be taken by Socrates students and Visiting students with the permission of the Department of History. Module HI1200 consists of two lectures each week throughout Michaelmas Term, together with a series of six tutorials, for which written assignments are required. The assessment of this module will take the form of: (1) an essay, which accounts for 20% of the over-all assessment of this module and (2) a two-hour examination in Trinity Term, which accounts for 80% of the over-all assessment. -

The House of Coburg and Queen Victoria: a Study of Duty and Affection

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 6-1-1971 The House of Coburg and Queen Victoria: A study of duty and affection Terrence Shellard University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Shellard, Terrence, "The House of Coburg and Queen Victoria: A study of duty and affection" (1971). Student Work. 413. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/413 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HOUSE OF COBURG AND QUEEN VICTORIA A STORY OF DUTY AND AFFECTION A Thesis Presented to the Department of History and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska at Omaha In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Terrance She Ha r d June Ip71 UMI Number: EP73051 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Diss««4afor. R_bJ .stung UMI EP73051 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. -

Intro & Table of Contents

Intro & Table of Contents KNOW THYSELF Observe, Meditate, Contemplate, Synthesize, Repeat There is nothing more true or real than your own experience Strive For Gnosis, Live With Love, Expand Your Perception, Strengthen Your Will Are you the thought or the thinker, the dream or the dreamer, the creation or the creator, the music or the musician, the art or the artist; maybe a bit of each? “Write your own Gospel, live your own myth” Miguel Conner “There is only one way and that is your way. There is only one salvation and that is your salvation. Why are you looking for help? Do you believe it will come from outside? What is to come will be created in you and from you. Hence look into yourself. Do not compare, do not measure. No other way is like yours. All other ways deceive and tempt you. You must fulfill the way that is in you.” –The Red Book Table of Contents Chapter 1 - Why? Chapter 2 - What is True? Chapter 3- Consciousness Chapter 4- What is Reality? Chapter 5- Reality Theories Chapter 6- My Truth, Tenets and Gospel Chapter 7-Additional Life Practices Chapter 8-The Simplicity of Magick Chapter 9- Master of Manipulation: The Cult of Inversion Chapter 10- My Three Wise-Men Chapter 11- Focus on the Good Compiled/Manifested by LoKe~KeLo Chapter 1- Why? Why are we here? What are you? What is the purpose? Is there a purpose? What’s this all about? Every religion, philosophy, and esoteric system tries to answer this, most believing they have. -

De Kwartierstaat Van Adriana Lissina Holland

een genealogieonline publicatie De kwartierstaat van Adriana Lissina Holland door Hans M. Flipse 28 september 2021 De kwartierstaat van Adriana Lissina Holland Hans M. Flipse De kwartierstaat van Adriana Lissina Holland Generatie 1 1. Adriana Lissina Holland, dochter van Marinus Rudolf Holland (volg 2) en Jacoba van der Horst (volg 3), is geboren op 5 augustus 1900 in Amsterdam. Adriana Lissina is overleden op 88 jarige leeftijd op 14 augustus 1988 in Amsterdam. Generatie 2 2. Marinus Rudolf Holland, zoon van Willem Carel Holland (volg 4) en Adriana Lissina Strunk (volg 5), is geboren op 3 juni 1874 in Amsterdam. Marinus Rudolf is overleden op 76 jarige leeftijd op 16 juni 1950 in Amsterdam en is begraven in Vredenhof. 3. Jacoba van der Horst, dochter van Johannes van der Horst (volg 6) en Wilhelmina van Veldhuizen (volg 7), is geboren op 2 september 1879 in Nijkerk, Gelderland, Nederland. Jacoba is overleden op 63 jarige leeftijd op 6 maart 1943 in Amsterdam. Generatie 3 4. Willem Carel Holland, zoon van Willem Holland (volg 8) en Anna Maria Wilhelmina Bartels (volg 9), is geboren op 10 mei 1842 in Amsterdam. Willem Carel is overleden op 69 jarige leeftijd op 5 april 1912 in Amsterdam. 5. Adriana Lissina Strunk, dochter van Hermann Henrich Strunk (volg 10) en Adriana Lissina Vreede (volg 11), is geboren op 25 mei 1845 in Amsterdam. Adriana Lissina is overleden op 80 jarige leeftijd op 1 februari 1926 in Amsterdam. 6. Johannes van der Horst, zoon van Johannes van der Horst (volg 12) en Jacoba van den Bor (volg 13), is geboren op 30 september 1849 in Nijkerk, Gelderland, Nederland. -

Recommended Sights in and Around Dresden1

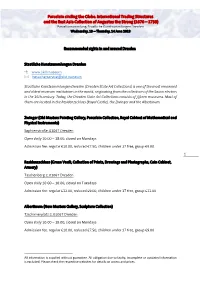

Porcelain circling the Globe. International Trading Structures and the East Asia Collection of Augustus the Strong (1670 – 1733) Porzellansammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden Wednesday, 13 – Thursday, 14 June 2018 Recommended sights in and around Dresden1 Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden www.skd.museum [email protected] Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (Dresden State Art Collections) is one of the most renowned and oldest museum institutions in the world, originating from the collections of the Saxon electors in the 16th century. Today, the Dresden State Art Collections consists of fifteen museums. Most of them are located in the Residenzschloss (Royal Castle), the Zwinger and the Albertinum. Zwinger (Old Masters Painting Gallery, Porcelain Collection, Royal Cabinet of Mathematical and Physical Instruments) Sophienstraße, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Mondays Admission fee: regular €10.00, reduced €7.50, children under 17 free, group €9.00 1 Residenzschloss (Green Vault, Collection of Prints, Drawings and Photographs, Coin Cabinet, Armory) Taschenberg 2, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Tuesdays Admission fee: regular €12.00, reduced €9.00, children under 17 free, group €11.00 Albertinum (New Masters Gallery, Sculpture Collection) Tzschirnerplatz 2, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Mondays Admission fee: regular €10.00, reduced €7.50, children under 17 free, group €9.00 All information is supplied without guarantee. All obligation due to faulty, incomplete or outdated -

King George and the Royal Family

ICO = 00 100 :LD = 00 CD "CO KING GEORGE AND THE ROYAL FAMILY KING GEORGK V Bust by Alfred Drury, K.A. &y permission of the sculptor KING GEORGE j* K AND THE ROYAL FAMILY y ;' ,* % j&i ?**? BY EDWARD LEGGE AUTHOR OF 'KING EDWARD IN HIS TRUE COLOURS' VOLUME I LONDON GRANT RICHARDS LTD. ST. MARTIN'S STREET MCMXVIII " . tjg. _^j_ $r .ffft* - i ' JO^ > ' < DA V.I PRINTED IN OBEAT BRITAIN AT THE COMPLETE PRESS WEST NORWOOD LONDON CONTENTS CHAP. PAQB I. THE KING'S CHARACTER AND ATTRIBUTES : HIS ACCESSION AND " DECLARATION " 9 II. THE QUEEN 55 " III. THE KING BETWEEN THE DEVIL AND THE DEEP SEA" 77 IV. THE INTENDED COERCION OF ULSTER 99 V. THE KING FALSELY ACCUSED OF " INTER- VENTION " 118 VI. THE MANTLE OF EDWARD VII INHERITED BY GEORGE V 122 VII. KING GEORGE AND QUEEN MARY IN PARIS (1914) 138 VIII. THE KING'S GREAT ADVENTURE (1914) 172 IX. THE MISHAP TO THE KING IN FRANCE, 1915 180 X. THE KING'S OWN WORDS 192 XI. WHY THE SOVEREIGNS ARE POPULAR 254 XII. THE KING ABOLISHES GERMAN TITLES, AND FOUNDS THE ROYAL HOUSE AND FAMILY OF WINDSOR 286 " XIII. " LE ROY LE VEULT 816 XIV. KING GEORGE, THE KAISER, HENRY THE SPY, AND MR. GERARD : THE KING'S TELE- GRAMS, AND OTHERS 827 f 6 CONTENTS CHAP. PAGE XV. KING GEORGE'S PARENTS IN PARIS 841 XVI. THE GREATEST OF THE GREAT GARDEN PARTIES 347 XVII. THE KING'S ACTIVITIES OUTLINED : 1910-1917 356 XVIII. THE CORONATION 372 ILLUSTRATIONS To face page KING GEORGE V Frontispiece His LATE MAJESTY KING EDWARD VII 40 PORTRAIT OF THE LATE PRINCESS MARY OF CAMBRIDGE 56 THE CHILDREN OF THE ROYAL FAMILY 74 THE KING AND QUEEN AT THE AMERICAN OFFICERS' CLUB, MAYFAIR 122 THE KING AND PRESIDENT POINCARE 138 THE QUEEN AND MADAME POINCARE 158 " HAPPY," THE KING'S DOG 176 A LUNCHEON PARTY AT SANDRINGHAM 190 His MAJESTY KING GEORGE V IN BRITISH FIELD-MARSHAL'S UNIFORM 226 FACSIMILES OF CHRISTMAS CARDS 268 H.R.H.