Nailed to the Craton: Stratigraphic Continuity Across the Southeastern Canadian Cordillera with Tectonic Implications for Ribbon Continent Models M.E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Montana Forest Insect and Disease Conditions and Program Highlights

R1-16-17 03/20/2016 Forest Service Northern Region Montata Department of Natural Resources and Conservation Forestry Division In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your completed form or letter to USDA by: (1) mail: U.S. -

Harry Butler Has Been Taken Into Custody for Violation of Donlan Law

people,of Montana, out of the great hearted generosity that has ever char acterized them, respond as liberally as may be possible in this emergency for- the relief of suffering that is daily becoming more distressing. Contri The Scenic theater was practically butions may be made to any member packed to its doors last Friday night of the Montana state board of the at 7:30, one half hour before the amaHarry Butler Has Been Taken Dilloninto Leads with Thirty-twoAmerican Red Cross, said board1 be teur performance began. Twelve num ing composed of the followingProposed citizens to Extend the Great bers were presented to an appreciativeCustody for Violation of Names, Wisdom next of this state: Edward J. Bowman, audience, Edward Hoffman receiving Anaconda, treasurer; Henry W. Row-Northern from Moccasin first prize, Miss Belle Holmes second Donlan Law. with Seven ley, Billings, secretary; F. S. Lusk, to the Capital and Miss Ruth Stoller third. The Missoula; T. A. Marlow, Helena; Ken SPEECH OF PATTERSON LIKED winner sang a song, little Miss HolmesSECURES VICTIMS WITH NOTES FIRST RAILROAD CASE MONDAY neth McLean, Miles City; W. M recited a poem and Miss Stoller sang Thornton, Great Falls. All fundsGILMORE thus & PITTSBURG LIKELY a song and then gave a fair imitationLuring Missives Will Be Used as received will be promptly remitted to Gives His Views on Roadways and Isof the skirt dance. The latter’s act Considerable Interest Manifested in A Portland Dispatch Says the G. A Interested in Park-to-Park Evidence Against Him in Com- These Cases—Burglary Trial the national treasurer of the Red CrossP. -

1 OUTREACH Kootenai National Forest Supervisor's Office, Fire and Aviation Management Forestry Technician GS-0462-05 IA Di

OUTREACH Kootenai National Forest Supervisor’s Office, Fire and Aviation Management Forestry Technician GS‐0462‐05 IA Dispatcher The Northern Region (R1), Kootenai National Forest, Supervisor’s Office, Fire and Aviation Management, GS‐0462‐05, position. Duty station is Libby, MT. This is a permanent seasonal 13/13 position. The results of the outreach will help determine the area of consideration for the vacancy announcement. Interested applicants are requested to respond utilizing the Employee Outreach Database. For Forest Service applicants the database is located in ConnectHR. For external applicants this may be accessed by an internet search for FS Outreach or the following link https://fsoutreach.gdcii.com/Outreach. Duties This position serves as a Fire Dispatcher located in an interagency (Forest Service and Montana Department of Natural Resources dispatch center. The center is responsible primarily for wildland fire preparedness and suppression support activities and may assist with all‐risk incidents as needed or directed. Work schedule may include weekends with days off during the week. Incumbent serves as a dispatcher, receiving, filling, and tracking resources requests for fire and other emergency incidents. Follows established procedures to perform a variety of technical duties common to the dispatch of personnel, equipment, aircraft and/or supplies according to 1 pre‐defined plans or in a response to resource orders from the field. Incumbent initiates requests to higher organizational levels for additional resources as needed. Collects, processes, collates and submits incident information to support fire operations (e.g. fire reports smoke permits, spot weather forecasts, prescribed fire burn requests). Processes and interprets weather information (e.g. -

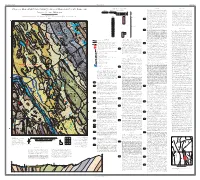

Geologic Map of the Line Point Quadrangle, Boundary County Idaho, and Lincoln County, Montana

IDAHO GEOLOGICAL SURVEY IDAHOGEOLOGY.ORG IGS DIGITAL WEB MAP 150 MONTANA BUREAU OF MINES AND GEOLOGY MBMG.MTECH.EDU MBMG OPEN FILE 623 white graded or nongraded argillite tops. Conspicuous bar code-like REFERENCES patterns in the middle, formed by alternating dark and light siltite, persist regionally (Huebschman, 1973) and have been used as markers for correla- GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE LINE POINT QUADRANGLE, BOUNDARY COUNTY, IDAHO, AND tion by Cominco (Hamilton and others, 2000). Siltite and argillite couplets, Anderson, H.E., and D.W. Davis, 1995, U-Pb geochronology of the Moyie sills, with dark, less commonly light tops, have even and parallel, uneven, wavy Purcell Supergroup, southeastern British Columbia: Implications for the or undulating lamination. Rusty nature of outcrop is due to weathering of Mesoproterozoic geological history of the Purcell (Belt) basin: Canadian CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS abundant sulfides, commonly pyrrhotite. Dominant lamination style and Journal of Earth Sciences, v. 32, no. 8, p. 1180-1193. LINCOLN COUNTY, MONTANA concentration of sulfides vary between members. Quartzite in 2-20 dm beds Anderson, H.E., and W.D. Goodfellow, 2000, Geochemistry and isotope chem- Alluvial and Colluvium and Glacial and Related Deposits is light weathering, averages about 60 percent quartz, 20 percent plagio- istry of the Moyie sills: Implications for the early tectonic setting of the Lacustrine Deposits Mass Wasting Deposits clase, with the rest mostly white micas and 5 percent biotite (Cressman, Mesoproterozoic Purcell basin, in J.W. Lydon, Trygve Höy, J.F. Slack, and 1989). Previous mapping in this area and to the east by Cressman and Harri- M.E. -

The Purcell Lava Glacier National Park, Montana

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The Purcell Lava Glacier National Park, Montana by Robert G. McGimsey 1 Open-File Report 85-0543 1985 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editoral standards and stratigraphic nomenclature Denver, Colorado CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES.......................................................... iii LIST OF TABLES........................................................... vii ABSTRACT................................................................. 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.......................................................... 2 CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION..................................................... 3 Purpose of Investigation....................................... 3 Location and Geologic Setting.................................. 3 Previous Work.................................................. 4 Field and Laboratory Methods................................... 5 II. DIVISION AND DESCRIPTION OF FACIES............................... 6 Introduction................................................... 6 Pillow Lava Facies............................................. 6 Two-Dimensional Pillow Exposures............................. 7 Three-Dimensional Pillow Exposures........................... 9 Isolated- and Broken-Pillow Breccia.......................... 9 Coalesced Pillows and the Upper Contact...................... 10 Hyaloclastite Breccia........................................ 10 Intercalated Sediment....................................... -

Squires Et Al 2012

Estimating detection probability for Canada lynx Lynx canadensis using snow-track surveys in the northern Rocky Mountains, Montana, USA Author(s): John R. Squires, Lucretia E. Olson, David L. Turner, Nicholas J. DeCesare & Jay A. Kolbe Source: Wildlife Biology, 18(2):215-224. Published By: Nordic Board for Wildlife Research DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2981/10-105 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.2981/10-105 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Wildl. Biol. 18: 215-224 (2012) Short communication DOI: 10.2981/10-105 Ó Wildlife Biology, NKV www.wildlifebiology.com Estimating detection probability for Canada lynx Lynx canadensis using snow-track surveys in the northern Rocky Mountains, Montana, USA John R. Squires, Lucretia E. Olson, David L. Turner, Nicholas J. DeCesare & Jay A. Kolbe We used snow-tracking surveys to determine the probability of detecting Canada lynx Lynx canadensis in known areas of lynx presence in the northern Rocky Mountains, Montana, USA during the winters of 2006 and 2007. -

Glacier National Park Geologic Resource Evaluation Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Geologic Resources Division Denver, Colorado Glacier National Park Geologic Resource Evaluation Report Glacier National Park Geologic Resource Evaluation Geologic Resources Division Denver, Colorado U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, DC Table of Contents List of Figures .............................................................................................................. iv Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 3 Purpose of the Geologic Resource Evaluation Program ............................................................................................3 Geologic Setting .........................................................................................................................................................3 Glacial Setting ............................................................................................................................................................4 Geologic Issues............................................................................................................. 9 Economic Resources..................................................................................................................................................9 Mining Issues..............................................................................................................................................................9 -

Geologic Map of the Curley Creek Quadrangle, Boundary County

IDAHO GEOLOGICAL SURVEY IDAHOGEOLOGY.ORG DIGITAL WEB MAP 148 MONTANA BUREAU OF MINES AND GEOLOGY MBMG.MTECH.EDU MBMG OPEN FILE 625 CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS Ravalli Group STRUCTURE GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE CURLEY CREEK QUADRANGLE, BOUNDARY COUNTY, IDAHO, AND The Ravalli Group that crosses the northeast quadrant of the map is only Alluvial and Colluvium and Glacial and Related Deposits slightly thicker than documented to the southeast (Cressman and Harrison, The major structure in this quadrangle is the Moyie fault. It is characterized Lacustrine Deposits Mass Wasting Deposits 1986) and south-southwest (Burmester and others, 2007). Although cosets regionally as an east-vergent thrust and juxtaposes older rocks on the west QalQQar lm Qt Qcg Qglc Holocene of thick sets of quartzite used to define the Revett elsewhere (Hayes, 1983; (hanging wall) against younger rocks on the east, consistent with this LINCOLN COUNTY, MONTANA Hayes and Einaudi, 1986) are rarely observed, Revett is mapped on the east interpretation. However, strata of the hanging and foot walls face each Quaternary side of the Sylvanite anticline, Fig. 1, (Cressman and Harrison, 1986) and Qgl Qgo Qg Qgt Qgk Pleistocene other, giving the impression that the fault occupies a syncline. Support for a correlated with the middle Creston north of the border where copper-silver- synclinal fold geometry comes from existence of a slightly east-verging, cobalt mineralization is similar to that in the Revett to the south (Hartlaub, southward-plunging syncline west of the Moyie fault south of the map, 1 1 1 1 2 Intrusive Rocks 2009). Revett mapped here as the swath of quartzite-rich strata below more Fig.1, (Miller and Burmester, 2004) and an open, northward-plunging Roy M. -

Cabinet-Yaak Grizzly Bear Recovery 2016 Research and Monitoring Progress Report

CABINET-YAAK GRIZZLY BEAR RECOVERY AREA 2016 RESEARCH AND MONITORING PROGRESS REPORT PREPARED BY WAYNE F. KASWORM, THOMAS G. RADANDT, JUSTIN E. TEISBERG, ALEX WELANDER, MICHAEL PROCTOR, AND HILARY COOLEY 2017 UNITED STATES FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE GRIZZLY BEAR RECOVERY COORDINATOR'S OFFICE UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA, MAIN HALL ROOM 309 MISSOULA, MONTANA 59812 (406) 243-4903 1 This annual report is cumulative and represents data collected since the inception of this monitoring program in 1983. New information collected or made available to this study is incorporated, reanalyzed, and summarized annually. Information in this report supersedes previous reports. Please obtain permission prior to citation. Cite this report as follows: Kasworm, W. F., T. G. Radandt, J.E. Teisberg, A. Welander, M. Proctor, and H. Cooley. 2017. Cabinet-Yaak grizzly bear recovery area 2016 research and monitoring progress report. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Missoula, Montana. 101 pp. ABSTRACT Sixteen grizzly bears were monitored with radio collars during portions of 2016. Research monitoring included seven females (three adults and four subadults) and nine males (five adults and four subadults) in the Cabinet-Yaak ecosystem (CYE). Two bears of these bears were from the Cabinet Mountains (1 subadult male and 1 subadult female) and part of the augmentation program. Grizzly bear monitoring and research has been ongoing in the Cabinet Mountains since 1988 and in the Yaak River since 1986. Sixty-eight resident bears have been captured and monitored through telemetry in the two areas from 1986-2016. Research in the Cabinet Mountains indicated that only a small population remained as of 1988. -

Mesoproterozoic–Early Cretaceous Provenance and Paleogeographic Evolution of the Northern Rocky Mountains

Mesoproterozoic–Early Cretaceous provenance and paleogeographic evolution of the Northern Rocky Mountains: Insights from the detrital zircon record of the Bridger Range, Montana, USA Chance B. Ronemus†, Devon A. Orme, Saré Campbell, Sophie R. Black, and John Cook Department of Earth Sciences, Montana State University, P.O. Box 173480, Bozeman, Montana 59717-3480, USA ABSTRACT Jurassic detritus into the foreland basin to rels et al., 1996, 2011; Gehrels and Ross, 1998; dominate by the Early Cretaceous. Park et al., 2010; Laskowski et al., 2013). These The Bridger Range of southwest Montana, ancient sources may consist of first-cycle grains USA, preserves one of the most temporally INTRODUCTION derived from Precambrian basement provinces extensive sedimentary sections in North or more recent magmatism. However, zircons America, with strata ranging from Meso- Sedimentary rocks in the Bridger Range of are more commonly sourced from erosion and proterozoic to Cretaceous in age. This study southwest Montana, USA, record the Mesopro- recycling of previously deposited sedimentary presents new detrital zircon geochronologic terozoic–Mesozoic history of sedimentation in rock (e.g., Schwartz et al., 2019). data from eight samples collected across this this region of North America, with Mesopro- The evolution of sedimentary provenance is mountain range. Multidimensional scaling terozoic to Cretaceous stratigraphy exposed as strongly influenced by tectonic factors (Gehrels, and non-negative matrix factorization sta- a generally eastward dipping homoclinal panel 2014). Tectonic events, such as rifting and moun- tistical analyses are used to quantitatively across the range (Fig. 1). The >8 km of stratig- tain building, trigger drainage reorganization unmix potential sediment sources from these raphy collectively record critical information and uplift new sediment sources. -

WEST KOOTENAY / REVELSTOKE DESTINATION DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY MONASHEE MOUNTAINS Photo: Ryan Creary

WEST KOOTENAY / REVELSTOKE DESTINATION DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY MONASHEE MOUNTAINS Photo: Ryan Creary DESTINATION BC Seppe Mommaerts MANAGER, DESTINATION DEVELOPMENT Jody Young SENIOR PROJECT ADVISOR, DESTINATION DEVELOPMENT [email protected] KOOTENAY ROCKIES TOURISM Emilie Cayer-Huard INDUSTRY & DESTINATION DEVELOPMENT SPECIALIST 250 427 4838 Ext.206 [email protected] MINISTRY OF TOURISM, ARTS AND CULTURE Amber Mattock DIRECTOR, LEGISLATION AND DESTINATION BC GOVERNANCE 250 356 1489 [email protected] INDIGENOUS TOURISM ASSOCIATION OF BC 604 921 1070 [email protected] WEST KOOTENAY/REVELSTOKE | 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .....................................................................1 7. STRATEGY AT A GLANCE ............................................................. 35 a. The West Kootenay/Revelstoke Area — A Distinctive Destination 8. STRATEGIC PRIORITIES ................................................................ 36 b. Destination Development in the West Kootenay/Revelstoke 8.1 Theme 1 — Improve Access, Signage and Infrastructure Area — A Distinctive Direction 8.1.1 Access 8.1.2 Signage II. ACRONYMS .........................................................................................7 8.1.3 Infrastructure 1. FOREWORD AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS...........................8 8.2 Theme 2 — Improve Business Operating Conditions 8.3 Theme 3 — Enhance Experiential Quality and Variety 2. INTRODUCING THE STRATEGY .................................................10 8.3.1 Experiential -

Wolverine Ecology and Conservation in the Western United States

Acta Universitatis Agriculturae Sueciae • 2013:4 No. Thesis Doctoral Doctoral Thesis No. 2013:4 This thesis focuses on wolverine ecology and conservation in the western Doctoral Thesis No. 2013:4 United States. The thesis covers the wolverine’s niche, scale of effective Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences management, and conservation priorities; it also examines the institutional system in place for delivering conservation actions for non-game species like wolverines. The analyses presented include home range size, movement Ecology and Conservation in the Western… Wolverine Wolverine Ecology and Conservation in rates, social organization, density, dispersal, reproductive chronology, habitat the Western United States selection, and connectivity. This thesis provides information that can facilitate recovery and management of this candidate endangered species. Robert Michael Inman Robert Michael Inman received his Master and Bachelor of Science degrees from the University of Tennessee, Department of Forestry, Wildlife and Fisheries. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae Sueciae presents doctoral theses from the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU). SLU generates knowledge for the sustainable use of biological natural • Robert Michael Inman • Robert Michael resources. Research, education, extension, as well as environmental monitoring and assessment are used to achieve this goal. Online publication of thesis summary: http://epsilon.slu.se/eindex.html ISSN 1652-6880 ISBN 978-91-576-7761-7 Wolverine Ecology and Conservation in the Western United States Robert Michael Inman Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Ecology Uppsala Doctoral Thesis Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Uppsala 2013 Acta Universitatis agriculturae Sueciae 2013:4 Cover: F121 and two cubs of the year in the Gravelly Range of Montana, USA.