Marylebone Cricket Club

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Impact 2018/2019

OUR IMPACT 2018/2019 ENHANCING LIVES THROUGH CRICKET Thank You From Our Chairman The last eighteen months – from April 2018 when we launched our Friends fundraising scheme, to the summer of 2019 when we saw, for the first time, Hub cricketers take on MCC teams across the UK – have been momentous for the MCC Foundation. We ran 50 Hubs over 2018/19 and will expand to 54 in 2019/20; we held our first Activation Day during a Test Match at Lord’s, raising our profile amongst English and Irish fans; we broke the world record for the longest indoor cricket match; and we funded a totally new cricket league for state- educated secondary school students in Westminster. This year has also seen more people than ever before join our community of supporters. Your generosity and enthusiasm has enabled us to be more ambitious in our remit, and build sustainable plans for the future. I would particularly like to thank our Benefactors, whose generosity has totally transformed the impact we are able to make. Looking to the future, we will focus on ensuring our Hubs target areas of greatest need and, in addition to continuing to provide opportunities for people across the UK, we want to deliver projects overseas. I hope that, in reading this, you will be proud of the good work we have achieved together. With best wishes, Phillip Hodson The Hubs provided 2,6002,600 HOURSHOURS of coaching & match play The MCC Foundation Cricket Hubs 2018/19 has been another successful year for our cricket 81% of participants said the Hub Hubs, and we are delighted to be in a position to expand improved their tactical and enhance the programme next year. -

E Calendar Spread 2 Col.Eng.Ps

16: FA Cup fifth round. England (Hamilton). FOOTBALL 15-18: Irish Open (Limerick). 16-22: Nottingham Open CRICKET GOLF J A N U A R Y 19-20: Champions League second 13-17: Second Test – New Zealand v 1-2: Champions League quarter-final 22-25: BMW PGA Championship (Nottingham). 7-11: Fourth npower Test: England v 4-7: Omega European Masters round first legs. England (Wellington). first legs. (Wentworth). 16-22: International Open South Africa (Brit Oval). (Crans-sur-Sierre). A v i n t a g e 21: UEFA Cup third round second legs. 22-26: Third Test – New Zealand v 3: UEFA Cup quarter-final first legs. 29-Jun 1: Celtic Manor Wales Open (Eastbourne). 16: Friends Provident Trophy final 19-21: Ryder Cup (Kentucky). W h o w i l l ATHLETICS 24: Carling Cup final (Wembley). England (Napier). 5-6: FA Cup semi-finals. (Newport). 23-Jul 6: Wimbledon. (Lord’s). 25-28: Quinn Direct British Masters 5: International Cross-Country (Belfast). 8-9: Champions League quarter-final 20: NatWest International Twenty20: (The Belfry). 12: Great Edinburgh International GOLF FOOTBALL MOTORCYCLING second legs. England v South Africa (Riverside). Cross-Country. 7-10: AT&T Pebble Beach Pro-Am 4-5: Champions League second round 4: MotoGP (China). y e a r f o r 10: UEFA Cup quarter-final second 22: NatWest Series: England v South MOTORCYCLING b e o n t h e 26: Norwich Union International (California). second legs. 18: MotoGP (France). J U L Y legs. Africa (Headingley Carnegie). 14: MotoGP (USA). -

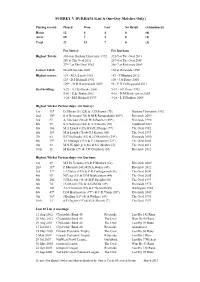

SURREY V SUSSEX (List a One-Day Matches Only)

SURREY V SUSSEX (List A One-Day Matches Only) Playing record: Played Won Lost Tied No Result (Abandoned) Home 29 13 14 0 2 (2) Away 37 14 20 1 2 (1) Total 66 27 34 1 4 (3) For Surrey For Sussex Highest Totals: 346-3 at Hove 2008 323-8 at Hove 2002 337-3 at Hove 2002 313-7 at Hove 2009 311-6 at Hove 2009 310-9 at Hove 1993 Lowest Total: 125 at Hove 1964 95 at The Oval 1970 125 at Hove 1972 Highest scores: 142* - M.R.Ramprakash 2007 144 - M.W.Goodwin 2009 130 - S.A.Newman 2009 117 - R.D.V.Knight 1977 126* - U.Afzaal 2008 117 - M.P.Speight 1996 Best bowling: 5-20 - E.S.H.Giddins 2002 5-15 - J.A.Snow 1972 5-31 - C.P.Schofield 2009 5-28 - A.C.S.Pigott 1982 5-44 - A.J.Hollioake 1996 4-23 - B.V.Taylor 2002 Highest Wicket Partnerships - for Surrey: 1st 154 S.A.Newman (130) & M.J.Brown (66) Hove 2009 2nd 151* A.D.Brown (117*) & A.J.Stewart (61*) Hove 1996 3rd 153 M.R.Ramprakash (63) & U.Afzaal (126*) Hove 2008 4th 148* M.R.Ramprakash (107*) & A.J.Hollioake (117*) Hove 2002 5th 89 G.P.Thorpe (53) & A.J.Hollioake (36) Horsham 1995 6th 75 Intikhab Alam (32) & A.Long (43) The Oval 1970 7th 63 A.J.Stewart (36) & G.Monkhouse (27) Hove 1983 8th 44* D.M.Ward (60*) & R.W.Nowell (15*) The Oval 1995 44 J.N.Batty (23*) & I.D.K.Salisbury (22) The Oval 1998 9th 32 G.Monkhouse (24*) & P.I.Pocock (14) Hove 1985 10th 26 A.C.S.Pigott (19*) & C.G.Rackemann (12) Horsham 1995 Highest Wicket Partnerships - for Sussex: 1st 162 D.M.Smith (52) & F.D.Stephenson (103) Hove 1993 2nd 117 M.A.Buss (63) & R.M.Prideaux (72) Hove 1973 117 C.W.J.Athey (97) & N.J.Lenham (73*) The -

Issue 40: Summer 2009/10

Journal of the Melbourne Cricket Club Library Issue 40, Summer 2009 This Issue From our Summer 2009/10 edition Ken Williams looks at the fi rst Pakistan tour of Australia, 45 years ago. We also pay tribute to Richie Benaud's role in cricket, as he undertakes his last Test series of ball-by-ball commentary and wish him luck in his future endeavours in the cricket media. Ross Perry presents an analysis of Australia's fi rst 16-Test winning streak from October 1999 to March 2001. A future issue of The Yorker will cover their second run of 16 Test victories. We note that part two of Trevor Ruddell's article detailing the development of the rules of Australian football has been delayed until our next issue, which is due around Easter 2010. THE EDITORS Treasures from the Collections The day Don Bradman met his match in Frank Thorn On Saturday, February 25, 1939 a large crowd gathered in the Melbourne District competition throughout the at the Adelaide Oval for the second day’s play in the fi nal 1930s, during which time he captured 266 wickets at 20.20. Sheffi eld Shield match of the season, between South Despite his impressive club record, he played only seven Australia and Victoria. The fans came more in anticipation games for Victoria, in which he captured 24 wickets at an of witnessing the setting of a world record than in support average of 26.83. Remarkably, the two matches in which of the home side, which began the game one point ahead he dismissed Bradman were his only Shield appearances, of its opponent on the Shield table. -

Race and Cricket: the West Indies and England At

RACE AND CRICKET: THE WEST INDIES AND ENGLAND AT LORD’S, 1963 by HAROLD RICHARD HERBERT HARRIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON August 2011 Copyright © by Harold Harris 2011 All Rights Reserved To Romelee, Chamie and Audie ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My journey began in Antigua, West Indies where I played cricket as a boy on the small acreage owned by my family. I played the game in Elementary and Secondary School, and represented The Leeward Islands’ Teachers’ Training College on its cricket team in contests against various clubs from 1964 to 1966. My playing days ended after I moved away from St Catharines, Ontario, Canada, where I represented Ridley Cricket Club against teams as distant as 100 miles away. The faculty at the University of Texas at Arlington has been a source of inspiration to me during my tenure there. Alusine Jalloh, my Dissertation Committee Chairman, challenged me to look beyond my pre-set Master’s Degree horizon during our initial conversation in 2000. He has been inspirational, conscientious and instructive; qualities that helped set a pattern for my own discipline. I am particularly indebted to him for his unwavering support which was indispensable to the inclusion of a chapter, which I authored, in The United States and West Africa: Interactions and Relations , which was published in 2008; and I am very grateful to Stephen Reinhardt for suggesting the sport of cricket as an area of study for my dissertation. -

Yorkshire County Cricket Club Annual Report and Accounts 2008

ANNUAL REPORT & ACCOUNTS 2008 BK0147 YCCC ANNUAL REPORTS 2009_V12.indd 1 10/2/09 16:26:47 CONTENTS NOTICE OF AGM AND AGENDA Notice of AGM and Agenda .....................................................3 Dear Member, Chairman’s Report ................................................................ 4-5 The Annual General Meeting of Members will be held in the East Stand Chief Executive’s Report ........................................................ 6-9 Long Room, Headingley Carnegie Cricket Ground on Saturday 14th March 2009 at 10:00 am for the purpose of transacting the following business: Director of Professional Cricket’s Report ........................... 10-11 President, Board Members, Staff and Players ....................... 12 Corporate Governance ........................................................... 13 AGENDA Income and Expenditure Account .......................................... 14 1. To receive apologies for absence. It would be appreciated if advance notice 9. (a) To elect Mr Robin Smith as a could be given of any questions which Vice President. Balance Sheet ......................................................................... 15 2. To confi rm the Minutes of the Annual might require some research in order to General Meeting held on Saturday 15th (b) To elect Mr Ken Taylor as a save time at the meeting. Cash Flow Statement/Analysis of Net Debt ........................... 16 March 2008. Vice President. 5. To receive a report from the Director Notes to the Accounts ....................................................... 17-23 If any Member has a query as to the 10. To update the members on progress in of Professional Cricket and to discuss accuracy of the Minutes then it would be developing the Headingley Carnegie Independent Auditor’s Report ................................................ 24 cricket matters. appreciated if this could be raised with Cricket Ground. 25 the Secretariat in advance in order to 6. To re-elect as President, Mr Brian Member’s Committee Report ................................................ -

Lord's Cricket Ground Case Study

LORD'S CRICKET GROUND SEES 70% IMPROVEMENT IN DISPATCH TIMES USING 24/7 SOFTWARE Je� Cards is Ground Superintendent for Lord’s Cricket Ground, owned by Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC). Before using 24/7 Software, Lord’s was utilizing outdated tools to communicate and respond to incidents, leading to delays and poor response times to customer needs. Lord’s recognized the need to change to a web-based software solution because their current processes did not meet their new About Lord’s Cricket Ground requirements, they wanted all stakeholders to use one software solution, and customer expectations Lord's Cricket Ground, commonly known as Lord's, is a changed. They needed software that would be cricket venue in St John's Wood, London. Named after accessible by all users, improve their response times to its founder, Thomas Lord, it is owned by Marylebone incidents and issues, allow monitoring of life-safety Cricket Club (MCC) and is the home of Middlesex County equipment throughout Lord’s Cricket Ground. These Cricket Club, the England and Wales Cricket Board (ECB), requirements led to Lord’s implementing 24/7 the European Cricket Council (ECC) and, until August Software’s Incident Management System. 2005, the International Cricket Council (ICC). Lord's is widely referred to as the Home of Cricket and is home to After deployment of 24/7 Software’s platform, Lord’s the world's oldest sporting museum. had a web-based software solution for all their stakeholders to use, a tool to learn about their Lord's today is not on its original site, being the third of operation’s performance and identify areas for three grounds that Lord established between 1787 and improvement & optimization, and access to �rst-class 1814. -

Marylebone Cricket Club (“MCC”) JOB PROFILE APPRENTICESHIP

Marylebone Cricket Club (“MCC”) JOB PROFILE APPRENTICESHIP Job Title Tennis & Squash Apprentice Department Tennis and Squash Reporting to Head Professional Tennis & Squash Dimensions of Role Hours: 40 working and study hours per week (five days out of seven) plus one unpaid lunch hour on each day worked. The court is open from 8 a.m. until 10 p.m. most weekdays and you will therefore be asked to work late and early hours as necessary, but no more than 40 hours per week. Key Purpose of Role To learn the role of a Club real tennis and squash professional, with the emphasis being on tennis. To work with and under the tutelage of the Club’s Head and Senior Professionals with the twin aims of delivering excellent services to Members and completing the basic training to become a real tennis professional. Actively contributing to the Department and taking on specific areas of responsibility, as defined. In addition, the role requires the undertaking of CPD (Club Professional Development) workshops and assessment sessions run by the Tennis and Rackets Association, with the aim of achieving level 1 CPD passes across all modules. Key Tasks and Accountabilities . Learning the Laws of Real Tennis and the Rules of Squash. Supporting the Professionals with induction sessions Members’ competitions, inter-club matches etc., Including developing new activities and tournaments where appropriate and promoting all events to Members. Helping to generate court bookings by improving communication with Members and other players. Playing tennis and squash with Members and receiving coaching sessions . Learning to coach and mark matches and, once trained, giving lessons, including introductory lessons and to Members. -

Class, Gender and the Context of Early Cricket

Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies Vol. 35 No. 2 (2012) View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE ‘Scorn Eunuch Sports’: Class, Gender and theprovided Context by MURAL - Maynooth University Research Archive Library of Early Cricketjecs_498 223..237 CONRAD BRUNSTRÖM andTANYA M. CASSIDY Abstract: The under-theorised eighteenth-century game of cricket represents a far more fluid and paradoxical site of enquiry than the exhaustively politicised discussions of the nineteenth- and twentieth-century versions of the sport. Eighteenth-century cricket represents a way of describing the performance of gender within a context of patriotic self-imagining. Poems and paintings describing cricketers of both sexes illustrate how ideas of masculinity and femininity can be celebrated and challenged at the same time. The extent to which cricket (as it is steadily organised and coded) functions as a ‘heroic’ pastime says much about the centrality of sport in general within the national consciousness. Keywords: cricket, sociology, gender, class, mock-heroic, leisure, consumption, identity Cricket’s early institutionalisation is contemporary with celebratory affirmations of its status as both a peculiarly English game and as a peculiarly masculinised one, a game to be contrasted with the more sedentary feminised pursuits of a continental (specifically French) aristocracy. Political analyses of sport are generally configured by describing the dynamics of class, race and gender which define the culture and assumptions of sporting endeavour. At the same time, gentility, ethnicity, masculinity and femininity are all variously staged, promoted and threatened by the celebration of sport. The assertive masculinity of the game of cricket coincides, meanwhile, with its popularity among women, both as a polite pastime and as a popular spectacle. -

Bowling Changes the Hambledon Club

No-Balls and Googlies A Cricket Companion THE HAMBLEDON CLUB Although historical evidence suggests that the game was first played in the BOWLING CHANGES Weald around Kent and Sussex, it is the Hambeldon Club of Hampshire that is generally perceived as cricket’s spiritual home. Founded around 1767, By the start of the nineteenth century the finest batsmen had mastered Hambledon was the leading club in England for some 30 years, regularly under-arm bowling. Lord Frederick Beauclerk, whose confidence was drawing crowds of 20,000 to its matches on Broad Halfpenny Down. An such that he used to hang his gold watch from the bails, averaged 61 in indication of its might was that in 1777 Hambledon scored 403 against All 1803. It was time for the country’s bowlers to try something new. Around England. Key players included the captain Richard Nyren, bowler David 1790 Hambledon’s Thomas Walker had attempted to bowl round-arm (his Harris, and master batsman John Small, reputedly the first man to abandon bowling arm level with his shoulder) but had been verbally abused for the old curved bat in favour of a straight blade. Hambledon’s influence was doing so and quickly returned to more conventional methods. Over in ended by the formation of the Marylebone Cricket Club, which attracted Kent John Willes was enjoying batting practice with his sister Christina in major players to London. a barn near their Canterbury home. Struggling to deliver the ball under- arm owing to the voluminous skirt she was wearing, she instead began Here lies, bowl’d out by Death’s unerring ball, bowling round-arm to him. -

SURREY V DURHAM (List a One-Day Matches Only)

SURREY V DURHAM (List A One-Day Matches Only) Playing record: Played Won Lost No Result (Abandoned) Home 12 8 4 0 (0) Away 10 7 3 0 (1) Total 22 15 7 0 (1) For Surrey For Durham Highest Totals: 330-6 at Durham University 1992 325-9 at The Oval 2011 289 at The Oval 2011 287-4 at The Oval 2009 279-7 at The Oval 1982 266-7 at Riverside 2009 Lowest Total: 86 at Riverside 2005 136 at Riverside 1998 Highest scores: 129 - M.A.Lynch 1982 143 - P.Mustard 2012 125 - D.J.Bicknell 1992 105 - J.A.Daley 2000 109* - M.R.Ramprakash 2009 96 - P.D.Collingwood 2011 Best bowling: 5-29 - A.J.Hollioake 2000 5-51 - S.P.Davis 1982 5-46 - Z.de Bruyn 2012 4-16 - D.M.Benkenstein 2005 4-28 - M.P.Bicknell 1997 4-28 - L.E.Plunkett 2005 Highest Wicket Partnerships - for Surrey: 1st 117 D.J.Bicknell (125) & A.D.Brown (75) Durham University 1992 2nd 109 S.A.Newman (70) & M.R.Ramprakash (109*) Riverside 2009 3rd 97 A.J.Stewart (58) & M.A.Butcher (85*) Riverside 1998 4th 99 S.A.Newman (84) & A.D.Brown (59) Guildford 2007 5th 166 M.A.Lynch (129) & G.R.J.Roope (77) The Oval 1982 6th 119 M.A.Lynch (78) & G.J.Kersey (50) The Oval 1993 7th 62 B.C.Hollioake (42) & J.D.Ratcliffe (25*) Riverside 2000 8th 39* T.J.Murtagh (31*) & P.J.Sampson (12*) The Oval 2005 9th 33 M.N.W.Spriegel (86) & S.C.Meaker (5) The Oval 2011 10th 11 M.Kartik (2*) & J.W.Dernbach (10) Riverside 2012 Highest Wicket Partnerships - for Durham: 1st 89 M.J.Di Venuto (29) & P.Mustard (61) Riverside 2009 2nd 119 P.Mustard (143) & B.A.Stokes (45) Riverside 2012 3rd 177 J.A.Daley (105) & P.D.Collingwood (86) The -

County Match Day Hospitality Packages Terms & Conditions

COUNTY MATCH DAY HOSPITALITY PACKAGES 2019 • 2020 • TERMS AND CONDITIONS • OCTOBER 2019 COUNTY MATCH DAY HOSPITALITY PACKAGES TERMS & CONDITIONS OCTOBER 2019 INFORMATION For all enquiries, please contact the Lord’s Operations Team on 01 020 7616 8563 or via email at [email protected]. Customers may book County Match Day Hospitality Packages (“Packages”) directly here (lords.org/cmdh) or they may purchase a County Match Day Hospitality Voucher (“Voucher”) online here (lords.org/cmdh). Early bookings are recommended to avoid disappointment. GENERAL 2.1 All bookings are subject to availability. 02 2.2 All bookings must be placed through lords.org/cmdh. Full payment is required to secure any booking. 2.3 Packages may be purchased on days one (1) to three (3) of any County Championship match. Please note that Packages are not available to be purchased for any Twenty20 matches, The Hundred matches, One-Day Internationals or Test Matches. 2.4 Any changes to a booking must be made at least 14 calendar days prior to the scheduled commencement of any Match, irrespective of the day for which the booking has been made. For example, if a booking is made for day three (3) of a Match, any changes to a booking must be made at least 14 calendar days prior day one of that Match. 2.5 If a booking is cancelled more than 14 calendar days prior to the scheduled commencement of any Match, a full refund will be issued less a £5 per person administrative charge. If a booking is cancelled 14 calendar days or less before the scheduled commencement of a Match, no refund will be issued.