Can a Tiger Change Its Stripes? the Politics of Conservation As Translated in Mudumalai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issn 0375-1511 Anuran Fauna of Rajiv Gandhi National Park, Nagarahole, Central Western Ghats, Karnataka, India

ISSN 0375-1511 Rec. zool. Surv. India: 112(part-l) : 57-69, 2012 ANURAN FAUNA OF RAJIV GANDHI NATIONAL PARK, NAGARAHOLE, CENTRAL WESTERN GHATS, KARNATAKA, INDIA. l 2 M.P. KRISHNA AND K.S. SREEPADA * 1 Department of Zoology, Field Marshal K.M.Cariappa Mangalore University College, Madikeri-571201, Karnataka, India. E.mail - [email protected] 2 Department ofApplied Zoology Mangalore University, Mangalagangothri 574199, Karnataka, India. E.mail- [email protected] (*Corresponding author) INTRODUCTION in the Nagarhole National Park is of southern tropical mixed deciduous both moist and dry with There are about 6780 species of amphibians in small patches of semi evergreen and evergreen the World (Frost,20ll). Approximately 314 species type (Lal Ranjit, 1994). Diversity, distribution are known to occur in India and about 154 from pattern, habitat specificity, abundance and global Western Ghats (Dinesh et al., 2009; Biju, 2010). threat status of the anurans recorded in the study However the precise number of species is not area are discussed. known since new frogs are being added to the checklist. Amphibian number has slowly started MATERIALS AND METHODS declining largely due to the anthropogenic activities. Anuran species diversity survey was under Habitat degradation and improper agricultural taken for the first time during January 2009 to activities are the major threats to amphibians. December 2009. The survey team comprised of a However, survey on amphibian diversity is limited group of 6-9 men including local people and forest to certain parts of Western Ghats in Karnataka department officials having thorough knowledge (Krishnamurthy and Hussain, 2000; Aravind et al., about the area. -

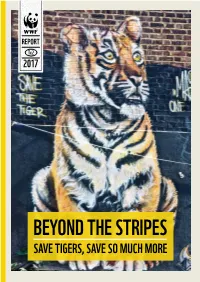

Beyond the Stripes: Save Tigers Save So

REPORT T2x 2017 BEYOND THE STRIPES SAVE TIGERS, SAVE SO MUCH MORE Front cover A street art painting of a tiger along Brick Lane, London by artist Louis Masai. © Stephanie Sadler FOREWORD: SEEING BEYOND THE STRIPES 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 INTRODUCTION 8 1. SAVING A BIODIVERSITY TREASURE TROVE 10 Tigers and biodiversity 12 Protecting flagship species 14 WWF Acknowledgements Connecting landscapes 16 WWF is one of the world’s largest and most experienced We would like to thank all the tiger-range governments, independent conservation organizations, with over partners and WWF Network offices for their support in the Driving political momentum 18 25 million followers and a global network active in more production of this report, as well as the following people in Return of the King – Cambodia and Kazakhstan 20 than 100 countries. particular: WWF’s mission is to stop the degradation of the planet’s Working Team natural environment and to build a future in which people 2. BENEFITING PEOPLE: CRITICAL ECOSYSTEM SERVICES 22 Michael Baltzer, Michael Belecky, Khalid Pasha, Jennifer live in harmony with nature, by conserving the world’s Safeguarding watersheds and water security 24 biological diversity, ensuring that the use of renewable Roberts, Yap Wei Lim, Lim Jia Ling, Ashleigh Wang, Aurelie natural resources is sustainable, and promoting the Shapiro, Birgit Zander, Caroline Snow, Olga Peredova. Tigers and clean water – India 26 reduction of pollution and wasteful consumption. Edits and Contributions: Sejal Worah, Vijay Moktan, Mitigating climate change 28 A WWF International production Thibault Ledecq, Denis Smirnov, Zhu Jiang, Liu Peiqi, Arnold Tigers, carbon and livelihoods – Russian Far East 30 Sitompul, Mark Rayan Darmaraj, Ghana S. -

National Parks in India (State Wise)

National Parks in India (State Wise) Andaman and Nicobar Islands Rani Jhansi Marine National Park Campbell Bay National Park Galathea National Park Middle Button Island National Park Mount Harriet National Park South Button Island National Park Mahatma Gandhi Marine National Park North Button Island National ParkSaddle Peak National Park Andhra Pradesh Papikonda National Park Sri Venkateswara National Park Arunachal Pradesh Mouling National Park Namdapha National Park Assam Dibru-Saikhowa National Park Orang National Park Manas National Park (UNESCO World Heritage Centre) Nameri National Park Kaziranga National Park (Famous for Indian Rhinoceros, UNESCO World Heritage Centre) Bihar Valmiki National Park Chhattisgarh Kanger Ghati National Park Guru Ghasidas (Sanjay) National Park Indravati National Park Goa Mollem National Park Gujarat Marine National Park, Gulf of Kutch Vansda National Park Blackbuck National Park, Velavadar Gir Forest National Park Haryana WWW.BANKINGSHORTCUTS.COM WWW.FACEBOOK.COM/BANKINGSHORTCUTS 1 National Parks in India (State Wise) Kalesar National Park Sultanpur National Park Himachal Pradesh Inderkilla National Park Khirganga National Park Simbalbara National Park Pin Valley National Park Great Himalayan National Park Jammu and Kashmir Salim Ali National Park Dachigam National Park Hemis National Park Kishtwar National Park Jharkhand Hazaribagh National Park Karnataka Rajiv Gandhi (Rameswaram) National Park Nagarhole National Park Kudremukh National Park Bannerghatta National Park (Bannerghatta Biological Park) -

Lllk Sabriel ~ Tl"L?BATES (English V (.Rsijn)

'~ries, Vol. XIV, No. IS Tuesday, July 28, 1992 Sravana 6, 1914./f-· , L-o -1' e-r£} LllK SABriel ~ Tl"l?BATES (English V (.rsiJn) Fourth Session (Tenth Lok Sabha) (Vol. XIV contains Nos. 11 to 20) LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI Price: Rs. 6.00 [OIuolNAJ. ENousH PR()CI!EDINOS INCLUDED IN ENousH VERSION AND ORJ PROCEI!DJNGS INCi:.tmeD IN HINDI VElISlON WIlL BE TREATI!D AS AtTL .... 1lJE.REOF.) CONTENTS [Tenth Series, Vol. XIV, Fourth Session, 199211914 (Saka)] No. 15, Tuesday, July 28, 19921Sravana 6,1914 (Saka) Cot.INNS swers to Ouestions: 1-31 . ·Starred Questions Nos. 285, 286, 289, 290 Answers to Ouestions: 32·345 Starred Questions Nos. 287, 288, 291-304 32-71 Unsbrred Questions Nos. 2977·3016. 71-345 3018·3061, 3063·3064, 3066·3119 Petition Re. Problems and Demands of Workers 347 of P-ilway Shramik Sangharsh Samiti. Moradabad "1c lion Re. Joint Committee on Offices of Profit 348 i:1usir.ass Advisory Committee Seventeenth Report - adopted 349-350 Matters under Rule 377 350-354 (i) Need to set up a Central University .in Mizoram 350 Dr. C. Silvera 350 (ii) Need 0 take steps to stop further deterioration of NTC mills 350-351 Shri Sharad Dighe 350-351 (iii) Need to clear all pending power projects of Karnataka 351 Shri V. Dhananjaya Kumar 351 . '!!gn +marked above the name of a Member indicates that the question was actually r\§,,,ijO on the floor of the House by that Member. COllA1NS (iv) Need for early approval to the construction 351-352 of bridge on the rivur Ujhar on Highway No. -

Protected Areas in News

Protected Areas in News National Parks in News ................................................................Shoolpaneswar................................ (Dhum- khal)................................ Wildlife Sanctuary .................................... 3 ................................................................... 11 About ................................................................................................Point ................................Calimere Wildlife Sanctuary................................ ...................................... 3 ......................................................................................... 11 Kudremukh National Park ................................................................Tiger Reserves................................ in News................................ ....................................................................... 3 ................................................................... 13 Nagarhole National Park ................................................................About................................ ......................................................................................................................................... 3 .................................................................... 14 Rajaji National Park ................................................................................................Pakke tiger reserve................................................................................. 3 ............................................................................... -

Download Download

PLATINUM The Journal of Threatened Taxa (JoTT) is dedicated to building evidence for conservaton globally by publishing peer-reviewed artcles online OPEN ACCESS every month at a reasonably rapid rate at www.threatenedtaxa.org. All artcles published in JoTT are registered under Creatve Commons Atributon 4.0 Internatonal License unless otherwise mentoned. JoTT allows allows unrestricted use, reproducton, and distributon of artcles in any medium by providing adequate credit to the author(s) and the source of publicaton. Journal of Threatened Taxa Building evidence for conservaton globally www.threatenedtaxa.org ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) | ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Communication Colour aberration in Indian mammals: a review from 1886 to 2017 Anil Mahabal, Radheshyam Murlidhar Sharma, Rajgopal Narsinha Patl & Shrikant Jadhav 26 April 2019 | Vol. 11 | No. 6 | Pages: 13690–13719 DOI: 10.11609/jot.3843.11.6.13690-13719 For Focus, Scope, Aims, Policies, and Guidelines visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/editorialPolicies#custom-0 For Artcle Submission Guidelines, visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/submissions#onlineSubmissions For Policies against Scientfc Misconduct, visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/editorialPolicies#custom-2 For reprints, contact <[email protected]> The opinions expressed by the authors do not refect the views of the Journal of Threatened Taxa, Wildlife Informaton Liaison Development Society, Zoo Outreach Organizaton, or any of the partners. The journal, the publisher, -

List of National Parks in India

www.gradeup.co List of National Parks in India Protected areas of India • These are defined according to the guidelines prescribed by IUCN (The International Union for Conservation of Nature). • There are mainly four types of protected areas which are- (a) National Park (b) Wildlife Sanctuaries (c) Conservation reserves (d) Community reserves (a) National Park • Classified as IUCN category II • Any area notified by state govt to be constituted as a National Park • There are 104 national parks in India. • First national park in India- Jim Corbett National Park (previously known as Hailey National Park) • No human activity/ rights allowed except for the ones permitted by the Chief Wildlife Warden of the state. • It covered 1.23 Percent geographical area of India (b) Wildlife Sanctuaries • Classified as IUCN category II • Any area notified by state govt to be constituted as a wildlife sanctuary. • Certain rights are available to the people. Example- grazing etc. • There are 543 wildlife sanctuaries in India. • It covered 3.62 Percent geographical area of India (c) Conservation reserves • These categories added in Wildlife (Protection) Amendment Act of 2002. • Buffer zones between established national parks, wildlife sanctuaries and reserved and protected forests of India. • Uninhabited and completely owned by the Government. • It covered 0.08 Percent geographical area of India (d) Community reserves • These categories added in Wildlife (Protection) Amendment Act of 2002. • Buffer zones between established national parks, wildlife sanctuaries and reserved and protected forests of India. • Used for subsistence by communities and community areas because part of the land is privately owned. • It covered 0.002 Percent geographical area of India Act related to wildlife 1 www.gradeup.co • Wildlife Protection Act 1972 • It is applicable to whole India except Jammu and Kashmir which have their own law for wildlife protection. -

80 Spotlight Karnataka

SPOTLIGHT KARNATAKAFESTIVALS ON THE WILD SIDE The flora and fauna of Karnataka is diverse and with forests covering around 20 per cent of the state’s geographic area, there are many secrets to uncover. BY BINDU GOPAL RAO o you know that Karnataka has BANDIPUR NATIONAL PARK one of the highest populations Among one of the most well-known national of tigers in the country? Well it parks in the state, the Bandipur National is not just tigers but a variety of Park is located in Chamarajanagar district Danimals and birds that you can see in this adjoining the Mudumalai National Park in state. With a plethora of wildlife sanctuaries, Tamil Nadu, Wayanad Wildlife Sanctuary in national parks, forest reserves, bird Kerala and the Nagarhole National Park in sanctuaries and conservation centres, Karnataka. Located about 60 km from Karnataka is a potpourri of experiences Mysore, this park was set up by the Mysore when it comes to experiencing all things in Maharaja in 1931. Located at the foot of the the wild. We list the places that you must Nilgiri Hills, this place is home to many definitely see if you are a lover of wildlife. tigers, Asian elephants, leopards, dhole, gaur and sloth bears. Being part of the Nilgiri ANSHI NATIONAL PARK Biosphere Reserve, the topography is a mix Extending about 340 sq km, the Anshi of tropical mixed deciduous forests that National Park is 60 km from Karwar in support a large diversity of animal and bird Uttara Karnataka and is adjoining the life. There are close to 350 species of birds Dandeli Wildlife Sanctuary. -

UNIT 11 WILDLIFE SANCTUARIES and NATIONAL PARK Structure 11.0 Objectives 11.1 Introduction 11.2 Wildlife Reserves, Wildlife Sanc

UNIT 11 WILDLIFE SANCTUARIES AND NATIONAL PARK Structure 11.0 Objectives 11.1 Introduction 11.2 Wildlife Reserves, Wildlife Sanctuaries and National Parks: Concept and Meaning 11.3 Tiger Reserves 11.4 Project Elephant 11.5 Indian Wildlife Sanctuaries and National Parks and their specialties 11.6 Wildlife National Parks Circuits of India 11.7 Jeep Safari and Wildlife Tourism 11.8 Let us sum up 11.9 Keywords 11.10 Some Useful books 11.11 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 11.12 Reference and bibliography 11.13 Terminal Questions 11.0 OBJECTIVES After studying this unit, learners should be able to: understand about Wildlife Reserves, National Parks and Sanctuaries differentiate between National Parks and Sanctuaries learn about various famous National Parks and Sanctuaries and their main attractions understand about Wildlife Protection Act of India explore Tiger Reserves and Elephant Reserves explain Wildlife Tourism 11.1 INTRODUCTION Wildlife of India is important natural heritage and tourism attraction. National Parks, Biosphere Reserves and Wildlife Sanctuaries which are important parts of tourism attraction protect the unique wildlife by acting as reserve areas for threatened species. Wildlife tourism means human activity undertaken to view wild animals in a natural setting. All the above areas are exclusively used for the benefit of the wildlife and maintaining biodiversity. “Wildlife watching” is simply an activity that involves watching wildlife. It is normally used to refer to watching animals, and this distinguishes wildlife watching from other forms of wildlife-based activities, such as hunting. Watching wildlife is essentially an observational activity, although it can sometimes involve interactions with the animals being watched, such as touching or feeding them. -

Jungle Trails

India Wildlife Exploration – Jungle Trails Itinerary India • Jungle Trails of South India Bangalore – Nagarhole National Park – Bandipur National Park – 14 Days • 13 Nights Mudumalei National Park – Munnar – Eravikulam National Park – Periyar National Park – Kumarakom Bird Sanctuary – Alappuzha – Kochi TOUR ESSENTIALS HIGHLIGHTS Bandipur and Periyar National Parks Tour Style Wildlife Exploration Elephants of Nagarahole Tour Start Bangalore Mudumalai, the Wildlife Corridor Tour End Bangalore Kerala's tea city - Munnar Niligiri Tahrs of Eravikulam Accommodation Hotel Included Meals 13 Breakfasts, 12 lunches, 12 Dinners Difficulty Level Medium Jungle Trails Discover the unique beauty of South India! Explore Mudumalai and Bandipur, go boating in Periyar, look out for the rare Nilgiri Tahr in Eravikulam, see the Elephants of Nagarahole and marvel at the birds of Kumarakom. Round off your adventure with a Houseboat cruise down the scenic backwaters of Kerala! This trip offers a complete wildlife experience not generally explored by the traveller to India. As well as the majestic tiger, India is also home to striped hyena, red panda, one horned rhino’s as well as a huge offering of other animals, birds and flora. Ina01 Pioneer Expeditions ● 4 Minster Chambers● 43 High Street● Wimborne ● Dorset ● BH21 1HR t 01202 798922 ● e [email protected] India, an overview Tourism in India has significant potential considering the rich cultural and historical heritage, variety in ecology, terrains and places of natural beauty spread across the country. The amount of tourists visiting India is increasing as India’s economy is growing fast. India has the second largest population in the world, the capital of India is New Delhi. -

LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version)

Tenth Series, Vol. XL, No. 28 Tuesday, May 16, 1995 Vaisakba 26, 1917 (Saka) LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version) Thirteenth Session (Tenth Lok Sabha) (Vol. XL contains Nos. 21 to 30) LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI Price,' Rs. 50.00 [ORIGINAL ENGLISH PIlOCEEDINGS INCLUDW IN ENGLlStl VERSION AND ORIGINAL HINDI PROCEEDINOS INCLUDED IN HINDI VERSION WILL BE TREATED AS AUTHORITATIVE AND NOT THE TRANSLATION TlfEREOF} CONTENTS [Tenth Series, Vol. XL, Thirteenth Session, 199511917 (Saka)] No. 28, Tuesday, May 16, 1995Naisakha 26, 1917 (Saka) COLUMNS ORAL ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS 'Starred Questions Nos. 562 and 563 1-19 WRIDEN ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS 'Starred Questions Nos. 561 and 564-580 19-35 Unstarred Questions Nos. 5729 to 5958 35-237 PAPERS LAID ON THE TABLE 259-261 COMMITTEE ON AGRICULTURE Twenty-fourth, Twenty-fifth, Twenty-sixth Twenty-seventh and Twenty-eighth Reports - Presented 262 STATEMENT BY MINISTER Accident involving 6019 Madras-Kanya Kumari Express and Empty Goods train Shri C.K. Jaffer Sharief 243-244 STATEMENT CORRECTING REPL~ TO STARRED QUESTION NO. 397 DT. 2.5.95 RE : ISSUE PRICE OF FOOD GRAINS 262-263 MAnERS UNDER RULE 377 (i) Need for construction of a bye-pass on National Highway No. 52 at North Lakhimpur, Assam Shri Balin Kuli 263-264 (ii) Need to give clearance to the pending irrigation projects of Vldarbha region of Maharashtra Shri Shantaram Potdukhe 264 (iii) Need to stop shifting of Research and Development wing of the Government gun carriage factory, Jabalpur to Pune Shri Shravan Kumar Patel 264-265 (iv) Need to grant statehood to Vidarbha Shri Uttamrao Deorao Patil 265 (v) Need to set up L.P.G. -

(Nagarahole) National Park

Insights from a Cultural Landscape: Lessons from Landscape History for the Management of Rajiv Gandhi (Nagarahole) National Park Sanghamitra Mahanty National Parks like the Rajiv Gandhi (Nagarahole) National Park can be seen as cultural landscapes that embody and reflect the historical, social and economic relationships between people and place. This article highlights that complex social relationships and processes of change underlie contemporary park management issues, such as conflict over the future of forest dwelling communities, resource dependent populations on the forest fringe and crop raiding by wildlife from the park. The article suggests that a cultural landscape framework, based on recog- nition of historical, social and economic relationships in the landscape, can provide a deeper understanding of these issues and needs to inform discussion on future management directions. Specifically, a historical approach highlights the changing situation of tribal communities in the context of changing management paradigms, and the need for management approaches to go beyond highly localised actions to work with wider government policies and processes that influence land use and markets outside the park. INTRODUCTION PARKS LIKE THE Rajiv Gandhi (Nagarahole) National Park1 in Karnataka, southern India have a long history of human interaction. Yet, the historical dimensions of peoplelandscape ties, in and around parks, are not often recognised in contem- porary management approaches. This article considers how a historical under- standing of interactions between society and the physical landscape, can contribute Acknowledgements: This article is based on doctoral research undertaken at the National Centre for Development Studies, Australian National University. I am grateful to the Karnataka Forest Department for permission to undertake the research.