(Nagarahole) National Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6. the Indian Forest Service

6.1THE INDIAN FOREST SERVICE (APPOINTMENT BY PROMOTION) REGULATIONS, 1966 In pursuance of sub-rule (1) of rule 8 of the Indian Forest Service (Recruitment) Rules, 1966, the Central Government, in consultation with the State Governments and the Union Public Service Commission, hereby makes the following regulations namely: 1. Short title & commencement.- 1(1) These regulations may be called the Indian Forest Service (Appointment by promotion) Regulations 1966. 1(2) They shall be deemed to have come into force with effect from the 1st July 1966. 2. Definitions.- 2(1) In these regulations, unless the context otherwise requires : a) `Cadre Officer’ means a member of the Service; b) `Cadre Post’ means any of the posts specified as such in the regulations made under sub-rule (1) of rule 4 of the Cadre Rules; c) `Cadre Rules’ means the Indian Forest Service (Cadre) Rules, 1966; d) `Committee’ means the Committee set up in accordance with regulation 3; e) `Commission’ means the Union Public Service Commission; f) `Recruitment Rules’ means the Indian Forest Service (Recruitment) Rules, 1966; g) `State Government’ means: (i) in relation to a State in respect of which a separate cadre of the service exists, the Government of such State ; and 2(ii) in relation to a group of States in respect of which a Joint Cadre of the Service is constituted, the Joint Cadre Authority; (iii) in relation to a group of Union Territories , and in respect of which a joint cadre of the service is constituted, the Central Government. 3h) `Year’ means the period commencing of the first day of January and ending on 31st day of December of the same year. -

Unit 11 All India and Central Services

UNIT 11 ALL INDIA AND CENTRAL SERVICES Structure 1 1.0 Objectives 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Historical Development 1 1.3 Constitution of All India Services 1 1.3.1 Indian Administrative Service 1 1.3.2 Indian Police Service 1 1.3.3 Indian Forest Service 1 1.4 Importance of Indian Administrative Service 1 1.5 Recruitment of All India Services 1 1.5.1 Training of All India Services Personnel 1 1 5.2 Cadre Management 1 1.6 Need for All India Services 1 1.7 Central Services 1 1.7.1 Recwihent 1 1.7.2 Tra~ningand Cadre Management 1 1.7.3 Indian Foreign Service 1 1.8 Let Us Sum Up 1 1.9 Key Words 1 1.10 References and Further Readings 1 1.1 1 Answers to Check Your Progregs Exercises r 1.0 OBJECTIVES 'lfter studying this Unit you should be able to: Explain the historical development, importance and need of the All India Services; Discuss the recruitment and training methods of the All India Seryice; and Through light on the classification, recruitment and training of the Central Civil Services. 11.1 INTRODUCTION A unique feature of the Indian Administration system, is the creation of certain services common to both - the Centre and the States, namely, the All India Services. These are composed of officers who are in the exclusive employment of neither Centre nor the States, and may at any time be at the disposal of either. The officers of these Services are recruited on an all-India basis with common qualifications and uniform scales of pay, and notwithstanding their division among the States, each of them forms a single service with a common status and a common standard of rights and remuneration. -

Seed Leaflet

Pterocarpus marsupium Roxb Kundu, Maitreyee; Schmidt, Lars Holger Published in: Seed Leaflet Publication date: 2015 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Kundu, M., & Schmidt, L. H. (Ed.) (2015). Pterocarpus marsupium Roxb. Seed Leaflet, (163). Download date: 26. sep.. 2021 SEED LEAFLET No. 163 July 2015 . Pterocarpus marsupium Roxb Taxonomy and Nomenclature Species Name: Pterocarpus marsupium Roxb. Family: Fabaceae (Papilionaceae) Vernacular (Common name): Indian Kino tree or Ma- labar Kino tree (English), Bija sal, Venga (India) Distribution and habitat: The species is distributed in tropical moist and dry de- ciduous forests of most of the Indian peninsula includ- ing the states Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Orissa, West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh, Western Ghats, Kar- nataka, and Kerala of peninsular India, Sri Lanka and Nepal. It grows generally on hills or undulating lands or rocky grounds up to an altitude of 150 to 1100m. The average rainfall of its habitat ranges from 750 to 2000 mm even more in southern India. The maximum temperature ranges from 35oC to 48oC and the mini- mum 0oC to 18oC. It can thrive in wide variety of soils and geographical conditions such as, gneiss, quartzite, shale, conglomerates, sandstone and lateritic. It prefers well-drained alluvial and sandy loam to loamy soil. The species is moderate light demander and the young seed- lings are frost-tender. Uses The timber is moderately heavy, strong hard, durable crown. Bark is grey, rough 1.2-1.8cm thick, longitudi- and easy to saw. It is mostly used for constructional and nally fissured, scaly, blaze pink with whitish markings. -

Determinants and Consequences of Bureaucrat Effectiveness: Evidence

Determinants and Consequences of Bureaucrat Effectiveness: Evidence from the Indian Administrative Service∗ Marianne Bertrand, Robin Burgess, Arunish Chawla and Guo Xu† October 21, 2015 Abstract Do bureaucrats matter? This paper studies high ranking bureaucrats in India to examine what determines their effectiveness and whether effective- ness affects state-level outcomes. Combining rich administrative data from the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) with a unique stakeholder survey on the effectiveness of IAS officers, we (i) document correlates of individual bureaucrat effectiveness, (ii) identify the extent to which rigid seniority-based promotion and exit rules affect effectiveness, and (iii) quantify the impact of this rigidity on state-level performance. Our empirical strategy exploits variation in cohort sizes and age at entry induced by the rule-based assignment of IAS officers across states as a source of differential promotion incentives. JEL classifica- tion: H11, D73, J38, M1, O20 ∗This project represents a colloboration between the Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration (LBSNAA), the University of Chicago and London School of Economics. We are grateful to Padamvir Singh, the former Director of LBSNAA for his help with getting this project started. The paper has benefited from seminar/conference presentations at Berkeley, Bocconi, CEPR Public Economics Conference, IGC Political Economy Conference, LBSNAA, LSE, NBER India Conference, Stanford and Stockholm University. †Marianne Bertrand [University of Chicago Booth School of Business: Mari- [email protected]]; Robin Burgess [London School of Economics (LSE) and the International Growth Centre (IGC): [email protected]]; Arunish Chawla [Indian Administrative Service (IAS)]; Guo Xu [London School of Economics (LSE): [email protected]] 1 1 Introduction Bureaucrats are a core element of state capacity. -

Issn 0375-1511 Anuran Fauna of Rajiv Gandhi National Park, Nagarahole, Central Western Ghats, Karnataka, India

ISSN 0375-1511 Rec. zool. Surv. India: 112(part-l) : 57-69, 2012 ANURAN FAUNA OF RAJIV GANDHI NATIONAL PARK, NAGARAHOLE, CENTRAL WESTERN GHATS, KARNATAKA, INDIA. l 2 M.P. KRISHNA AND K.S. SREEPADA * 1 Department of Zoology, Field Marshal K.M.Cariappa Mangalore University College, Madikeri-571201, Karnataka, India. E.mail - [email protected] 2 Department ofApplied Zoology Mangalore University, Mangalagangothri 574199, Karnataka, India. E.mail- [email protected] (*Corresponding author) INTRODUCTION in the Nagarhole National Park is of southern tropical mixed deciduous both moist and dry with There are about 6780 species of amphibians in small patches of semi evergreen and evergreen the World (Frost,20ll). Approximately 314 species type (Lal Ranjit, 1994). Diversity, distribution are known to occur in India and about 154 from pattern, habitat specificity, abundance and global Western Ghats (Dinesh et al., 2009; Biju, 2010). threat status of the anurans recorded in the study However the precise number of species is not area are discussed. known since new frogs are being added to the checklist. Amphibian number has slowly started MATERIALS AND METHODS declining largely due to the anthropogenic activities. Anuran species diversity survey was under Habitat degradation and improper agricultural taken for the first time during January 2009 to activities are the major threats to amphibians. December 2009. The survey team comprised of a However, survey on amphibian diversity is limited group of 6-9 men including local people and forest to certain parts of Western Ghats in Karnataka department officials having thorough knowledge (Krishnamurthy and Hussain, 2000; Aravind et al., about the area. -

Updated Civil List of Indian Forest Service of West Bengal Cadre

INDIAN FOREST SERVICE (CIVIL LIST) AS ON 01.01.2021 (FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY) (THE CONTENTS OF THIS LIST SHOULD NOT BE DEEMED TO CONVEY ANY SANCTION OR AUTHORITY IN THE MATTER OF SENIORITY) Any error or suggestion for further improvement may kindly be informed at [email protected] DIRECTORATE OF FORESTS GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL GAZETTED CELL IFS Cadre of West Bengal as on 01.01.2021 Sl. Authorised Structure of the Cadre No of Present Srength No of No. vide G.O No. 16016/2(i)/2011-AIS- Post of Cadre as on Post (II)(A) dt.13.03.2012 01.01.2021 1 Senior Duty Post under the State Govt 78 Senior Duty Post 78* 2 Central Deputation Reserve @ 20% of 15 Central Deputation 7 (1) above 3 State Deputation Reserve @ 25% of (1) 19 State Deputation 20 above 4 Training Reserve @ 3.5% of (1) above 2 Training Reserve 8 5 Post to be filled by promotion in 38 Posts Filled by 33 accordance with Rule 8 of India Forest promotion from Service (Recruitment) Rules,1966 not WBFS exceeding 33.33% of items (1),(2),(3) & (4) above 6 Leave Reserve & Junior Posts Reserve 12 Leave Reserve & 1 @ 16.5% if item (1) above Junior Posts 7 Post to be filled by Direct Recruitment 88 Posts filled by 72 (1+2+3+4+6-5) Direct Recruitment 8 Total Authorised Strength 126 Total Present 105 Strength *Includes 12 IFS officers of Junior Time Scale holding Senior Duty Posts CIVIL LIST OF INDIAN FOREST SERVICE OF WEST BENGAL CADRE AS ON 01-01-2021 Sl No. -

Western Ghats & Sri Lanka Biodiversity Hotspot

Ecosystem Profile WESTERN GHATS & SRI LANKA BIODIVERSITY HOTSPOT WESTERN GHATS REGION FINAL VERSION MAY 2007 Prepared by: Kamal S. Bawa, Arundhati Das and Jagdish Krishnaswamy (Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology & the Environment - ATREE) K. Ullas Karanth, N. Samba Kumar and Madhu Rao (Wildlife Conservation Society) in collaboration with: Praveen Bhargav, Wildlife First K.N. Ganeshaiah, University of Agricultural Sciences Srinivas V., Foundation for Ecological Research, Advocacy and Learning incorporating contributions from: Narayani Barve, ATREE Sham Davande, ATREE Balanchandra Hegde, Sahyadri Wildlife and Forest Conservation Trust N.M. Ishwar, Wildlife Institute of India Zafar-ul Islam, Indian Bird Conservation Network Niren Jain, Kudremukh Wildlife Foundation Jayant Kulkarni, Envirosearch S. Lele, Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Environment & Development M.D. Madhusudan, Nature Conservation Foundation Nandita Mahadev, University of Agricultural Sciences Kiran M.C., ATREE Prachi Mehta, Envirosearch Divya Mudappa, Nature Conservation Foundation Seema Purshothaman, ATREE Roopali Raghavan, ATREE T. R. Shankar Raman, Nature Conservation Foundation Sharmishta Sarkar, ATREE Mohammed Irfan Ullah, ATREE and with the technical support of: Conservation International-Center for Applied Biodiversity Science Assisted by the following experts and contributors: Rauf Ali Gladwin Joseph Uma Shaanker Rene Borges R. Kannan B. Siddharthan Jake Brunner Ajith Kumar C.S. Silori ii Milind Bunyan M.S.R. Murthy Mewa Singh Ravi Chellam Venkat Narayana H. Sudarshan B.A. Daniel T.S. Nayar R. Sukumar Ranjit Daniels Rohan Pethiyagoda R. Vasudeva Soubadra Devy Narendra Prasad K. Vasudevan P. Dharma Rajan M.K. Prasad Muthu Velautham P.S. Easa Asad Rahmani Arun Venkatraman Madhav Gadgil S.N. Rai Siddharth Yadav T. Ganesh Pratim Roy Santosh George P.S. -

64Th ANNUAL REPORT

64th (2013-14) Annual Report UNION PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION Dholpur House, Shahjahan Road New Delhi – 110069 http: //www.upsc.gov.in The Union Public Service Commission have the privilege to present before the President their Sixty Fourth Report as required under Article 323(1) of the Constitution. This Report covers the period from April 1, 2013 (Chaitra 11, 1935 Saka) to March 31, 2014 (Chaitra 10, 1936 Saka). Annual Report 2013-14 Contents List of abbreviations ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- (ix) Composition of the Commission during the year 2013-14 ----------------------------- (xi) List of Chapters Chapter Heading Page No. 1 Highlights 1-3 2 Brief History and Workload over the years 5-10 3 Recruitment by Examinations 11-19 4 Direct Recruitment by Selection 21-27 5 Recruitment Rules, Service Rules and Mode of Recruitment 29-31 6 Promotions and Deputations 33-40 7 Representation of candidates belonging to Scheduled Castes, Scheduled 41-44 Tribes, Other Backward Classes and Persons with Disabilities 8 Disciplinary Cases 45-46 9 Delays in implementing advice of the Commission 47-48 10 Non-acceptance of the Advice of the Commission by the Government 49-70 11 Administration and Finance 71-72 12 Miscellaneous 73-77 Acknowledgement 79 List of Appendices Appendix Subject Page No. 1 Profiles of Hon’ble Chairman and Hon’ble Members of the Commission. 81-88 2 Recommendations made by the Commission – Relating to suitability of 89 candidates/officials. 3 Recommendations made by the Commission – Relating to Exemption 89 cases, Service matters, Seniority etc. 4 Recruitment by Examinations – Details of recommendations made during 90 the year 2013-14 for Civil Services/Posts. -

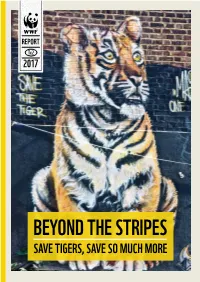

Beyond the Stripes: Save Tigers Save So

REPORT T2x 2017 BEYOND THE STRIPES SAVE TIGERS, SAVE SO MUCH MORE Front cover A street art painting of a tiger along Brick Lane, London by artist Louis Masai. © Stephanie Sadler FOREWORD: SEEING BEYOND THE STRIPES 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 INTRODUCTION 8 1. SAVING A BIODIVERSITY TREASURE TROVE 10 Tigers and biodiversity 12 Protecting flagship species 14 WWF Acknowledgements Connecting landscapes 16 WWF is one of the world’s largest and most experienced We would like to thank all the tiger-range governments, independent conservation organizations, with over partners and WWF Network offices for their support in the Driving political momentum 18 25 million followers and a global network active in more production of this report, as well as the following people in Return of the King – Cambodia and Kazakhstan 20 than 100 countries. particular: WWF’s mission is to stop the degradation of the planet’s Working Team natural environment and to build a future in which people 2. BENEFITING PEOPLE: CRITICAL ECOSYSTEM SERVICES 22 Michael Baltzer, Michael Belecky, Khalid Pasha, Jennifer live in harmony with nature, by conserving the world’s Safeguarding watersheds and water security 24 biological diversity, ensuring that the use of renewable Roberts, Yap Wei Lim, Lim Jia Ling, Ashleigh Wang, Aurelie natural resources is sustainable, and promoting the Shapiro, Birgit Zander, Caroline Snow, Olga Peredova. Tigers and clean water – India 26 reduction of pollution and wasteful consumption. Edits and Contributions: Sejal Worah, Vijay Moktan, Mitigating climate change 28 A WWF International production Thibault Ledecq, Denis Smirnov, Zhu Jiang, Liu Peiqi, Arnold Tigers, carbon and livelihoods – Russian Far East 30 Sitompul, Mark Rayan Darmaraj, Ghana S. -

Notes on Hawk Moths ( Lepidoptera — Sphingidae )

Colemania, Number 33, pp. 1-16 1 Published : 30 January 2013 ISSN 0970-3292 © Kumar Ghorpadé Notes on Hawk Moths (Lepidoptera—Sphingidae) in the Karwar-Dharwar transect, peninsular India: a tribute to T.R.D. Bell (1863-1948)1 KUMAR GHORPADÉ Post-Graduate Teacher and Research Associate in Systematic Entomology, University of Agricultural Sciences, P.O. Box 221, K.C. Park P.O., Dharwar 580 008, India. E-mail: [email protected] R.R. PATIL Professor and Head, Department of Agricultural Entomology, University of Agricultural Sciences, Krishi Nagar, Dharwar 580 005, India. E-mail: [email protected] MALLAPPA K. CHANDARAGI Doctoral student, Department of Agricultural Entomology, University of Agricultural Sciences, Krishi Nagar, Dharwar 580 005, India. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. This is an update of the Hawk-Moths flying in the transect between the cities of Karwar and Dharwar in northern Karnataka state, peninsular India, based on and following up on the previous fairly detailed study made by T.R.D. Bell around Karwar and summarized in the 1937 FAUNA OF BRITISH INDIA volume on Sphingidae. A total of 69 species of 27 genera are listed. The Western Ghats ‘Hot Spot’ separates these towns, one that lies on the coast of the Arabian Sea and the other further east, leeward of the ghats, on the Deccan Plateau. The intervening tract exhibits a wide range of habitats and altitudes, lying in the North Kanara and Dharwar districts of Karnataka. This paper is also an update and summary of Sphingidae flying in peninsular India. Limited field sampling was done; collections submitted by students of the Agricultural University at Dharwar were also examined and are cited here . -

Ethnobotanical Uses, Phytochemistry and Pharmacological Activities of Pterocarpus Marsupium: a Review

Pharmacogn J. 2018; 10(6)Suppl: s1-s8 A Multifaceted Journal in the field of Natural Products and Pharmacognosy Review Article www.phcogj.com | www.journalonweb.com/pj | www.phcog.net Ethnobotanical Uses, Phytochemistry and Pharmacological Activities of Pterocarpus marsupium: A Review Mohd Saidur Rahman, Md. Mujahid*, Mohd Aftab Siddiqui, Md. Azizur Rahman, Muhammad Arif, Shimaila Eram, Anayatullah Khan, Md Azeemuddin ABSTRACT Pterocarpus marsupium is an important therapeutic and medicinal plant belonging to fam- ily Fabaceae and commonly named as Indian Kino tree, Bijasal, Venga or Vijayasara. It is a huge deciduous plant and widely distributed in the Central, Western and Southern regions of India. Role of P. marsupium is found in Ayurveda, Homeopathic and Unani systems of medicine. It is a decent source of tannins and flavonoids hence, used as influential astringent, anodyne, cooling, regenerating agent and also used for the treatments of leprosy, leucoderma, toothache, fractures, diarrhea, passive hemorrhage, and dysentery, bruises and diabetes. It is also used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, gout, diabetic anemia, indigestion, asthma, cough, discoloration of hair, bronchitis, ophthalmic complications, elephantiasis and erysipelas. Re- searchers have been stated the presence of several phytoconstituents in P. marsupium and also their pharmacological activities. The current review aimed to define the phytochemical and pharmacological aspects of P. marsupium which will have been help in the researchers for further qualitative research. Mohd SaidurRahman, Key words: Pterocarpus marsupium, Indian Kino, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, Antidiabetic, Md. Mujahid*, Mohd Aftab Antioxidant, Tannin, Epicatechin. Siddiqui, Md. Azizur Rahman, Muhammad Arif, Shimaila INTRODUCTION Eram, Anayatullah Khan, Md Azeemuddin Plants are important to human being for his life. -

National Parks in India (State Wise)

National Parks in India (State Wise) Andaman and Nicobar Islands Rani Jhansi Marine National Park Campbell Bay National Park Galathea National Park Middle Button Island National Park Mount Harriet National Park South Button Island National Park Mahatma Gandhi Marine National Park North Button Island National ParkSaddle Peak National Park Andhra Pradesh Papikonda National Park Sri Venkateswara National Park Arunachal Pradesh Mouling National Park Namdapha National Park Assam Dibru-Saikhowa National Park Orang National Park Manas National Park (UNESCO World Heritage Centre) Nameri National Park Kaziranga National Park (Famous for Indian Rhinoceros, UNESCO World Heritage Centre) Bihar Valmiki National Park Chhattisgarh Kanger Ghati National Park Guru Ghasidas (Sanjay) National Park Indravati National Park Goa Mollem National Park Gujarat Marine National Park, Gulf of Kutch Vansda National Park Blackbuck National Park, Velavadar Gir Forest National Park Haryana WWW.BANKINGSHORTCUTS.COM WWW.FACEBOOK.COM/BANKINGSHORTCUTS 1 National Parks in India (State Wise) Kalesar National Park Sultanpur National Park Himachal Pradesh Inderkilla National Park Khirganga National Park Simbalbara National Park Pin Valley National Park Great Himalayan National Park Jammu and Kashmir Salim Ali National Park Dachigam National Park Hemis National Park Kishtwar National Park Jharkhand Hazaribagh National Park Karnataka Rajiv Gandhi (Rameswaram) National Park Nagarhole National Park Kudremukh National Park Bannerghatta National Park (Bannerghatta Biological Park)