The Living Scale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Racism and Stereotypes: Th Movies-A Special Reference to And

People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific ResearchResearch Larbi Ben M’h idi University-Oum El Bouaghi Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of English Racism and Stereotypes: The Image of the Other in Disney’s Movies-A Special Reference to Aladdin , Dumbo and The Lion King A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the D egree of Master of Arts in Anglo-American Studies By: Abed Khaoula Board of Examiners Supervisor: Hafsa Naima Examiner: Stiti Rinad 2015-2016 Dedication To the best parents on earth Ouiza and Mourad To the most adorable sisters Shayma, Imène, Kenza and Abir To my best friend Doudou with love i Acknowledgements First of all,I would like to thank ‘A llah’ who guides and gives me the courage and Patience for conducting this research.. I would like to express my deep appreciation to my supervisor Miss Hafsa Naima who traced the path for this dissertation. This work would have never existed without her guidance and help. Special thanks to my examiner Miss Stiti Rinad who accepted to evaluate my work. In a more personal vein I would like to thank my mother thousand and one thanks for her patience and unconditional support that facilitated the completion of my graduate work. Last but not least, I acknowledge the help of my generous teacher Mr. Bouri who believed in me and lifted up my spirits. Thank you for everyone who believed in me. ii ا ا أن اوات ا اد ر ر دة اطل , د ه اوات ا . -

Disney Syllabus 12

WS 325: Disney: Gender, Race, and Empire Women Studies Oregon State University Fall 2012 Thurs., 2:00-3:20 WLKN 231 (3 credits) Dr. Patti Duncan 266 Waldo Hall Office Hours: Mon., 2:00-3:30 and by appt email: [email protected] Graduate Teaching Assistant: Chelsea Whitlow [OFFICE LOCATION] Office Hours: Mon./Wed., 9:30-11:00 email: [email protected] __________________________________________________________________________________________________ CATALOGUE DESCRIPTION Introduces key themes and critical frameworks in feminist film theories and criticism, focused on recent animated Disney films. Explores constructions of gender, race, class, sexuality, and nation in these representations. (H) (Bacc Core Course) PREREQUISITES: None, but a previous WS course is helpful. COURSE DESCRIPTION In this discussion-oriented course, students will explore constructions of gender, race, class, sexuality, and nation in the recent animated films of Walt Disney. By examining the content of several Disney films created within particular historical and cultural contexts, we will develop and expand our understanding of the cultural productions, meanings, and 1 intersections of racism, sexism, classism, colonialism, and imperialism. We will explore these issues in relation to Disney’s representations of concepts such as love, sex, family, violence, money, individualism, and freedom. Also, students will be introduced to concepts in feminist film theory and criticism, and will develop analyses of the politics of representation. Hybrid Course This is a hybrid course, where approximately 50% of the course will take place in a traditional face-to-face classroom and 50% will be delivered via Blackboard, your online learning community, where you will interact with your classmates and with the instructor. -

The Lion King Audition Monologues

Audition Monologues Choose ONE of the monologues. This is a general call; the monologue you choose does not affect how you will be cast in the show. We are listening to the voice, character development, and delivery no matter what monologue you choose. SCAR Mufasa’s death was a terrible tragedy; but to lose Simba, who had barely begun to live... For me it is a deep personal loss. So, it is with a heavy heart that I assume the throne. Yet, out of the ashes of this tragedy, we shall rise to greet the dawning of a new era... in which lion and hyena come together, in a great and glorious future! MUFASA Look Simba. Everything the light touches is our kingdom. A king's time as ruler rises and falls like the sun. One day, Simba, the sun will set on my time here - and will rise with you as the new king. Everything exists in a delicate balance. As king, you need to understand that balance, and respect for all creatures-- Everything is connected in the great Circle of Life. YOUNG SIMBA Hey Uncle Scar, guess what! I'm going to be king of Pride Rock. My Dad just showed me the whole kingdom, and I'm going to rule it all. Heh heh. Hey, Uncle Scar? When I'm king, what will that make you? {beat} YOUNG NALA Simba, So, where is it? Better not be any place lame! The waterhole? What’s so great about the waterhole? Ohhhhh….. Uh, Mom, can I go with Simba? Pleeeez? Yay!!! So, where’re we really goin’? An elephant graveyard? Wow! So how’re we gonna ditch the dodo? ZAZU (to Simba) You can’t fire me. -

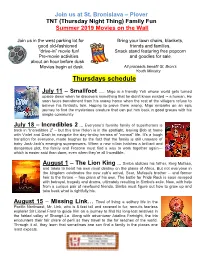

Thursdays Schedule

Join us at St. Bronislava – Plover TNT (Thursday Night Thing) Family Fun Summer 2019 Movies on the Wall Join us in the west parking lot for Bring your lawn chairs, blankets, good old-fashioned friends and families. “drive-in” movie fun! Snack stand featuring free popcorn Pre-movie activities and goodies for sale. about an hour before dusk. Movies begin at dusk. All proceeds benefit St. Bron’s Youth Ministry Thursdays schedule July 11 – Smallfoot … Migo is a friendly Yeti whose world gets turned upside down when he discovers something that he didn't know existed -- a human. He soon faces banishment from his snowy home when the rest of the villagers refuse to believe his fantastic tale. Hoping to prove them wrong, Migo embarks on an epic journey to find the mysterious creature that can put him back in good graces with his simple community July 18 – Incredibles 2 … Everyone’s favorite family of superheroes is back in “Incredibles 2” – but this time Helen is in the spotlight, leaving Bob at home with Violet and Dash to navigate the day-to-day heroics of “normal” life. It’s a tough transition for everyone, made tougher by the fact that the family is still unaware of baby Jack-Jack’s emerging superpowers. When a new villain hatches a brilliant and dangerous plot, the family and Frozone must find a way to work together again— which is easier said than done, even when they’re all Incredible. August 1 – The Lion King … Simba idolizes his father, King Mufasa, and takes to heart his own royal destiny on the plains of Africa. -

Animated Stereotypes –

Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Alexander Lindgren, 36761 Pro gradu-avhandling i engelska språket och litteraturen Handledare: Jason Finch Fakulteten för humaniora, psykologi och teologi Åbo Akademi 2020 ÅBO AKADEMI – FACULTY OF ARTS, PSYCHOLOGY AND THEOLOGY Abstract for Master’s Thesis Subject: English Language and Literature Author: Alexander Lindgren Title: Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Supervisor: Jason Finch Abstract: Walt Disney Animation Studios is currently one of the world’s largest producers of animated content aimed at children. However, while Disney often has been associated with themes such as childhood, magic, and innocence, many of the company’s animated films have simultaneously been criticized for their offensive and quite problematic take on race and ethnicity, as well their heavy reliance on cultural stereotypes. This study aims to evaluate Disney’s portrayals of racial and ethnic minorities, as well as determine whether or not the nature of the company’s portrayals have become more culturally sensitive with time. To accomplish this, seven animated feature films produced by Disney were analyzed. These analyses are of a qualitative nature, with a focus on imagology and postcolonial literary theory, and the results have simultaneously been compared to corresponding criticism and analyses by other authors and scholars. Based on the overall results of the analyses, it does seem as if Disney is becoming more progressive and culturally sensitive with time. However, while most of the recent films are free from the clearly racist elements found in the company’s earlier productions, it is quite evident that Disney still tends to rely heavily on certain cultural stereotypes. -

Historical Inaccuracies and a False Sense of Feminism in Disney’S Pocahontas

Cyrus 1 Lydia A. Cyrus Dr. Squire ENG 440 Film Analysis Revision Fabricated History and False Feminism: Historical Inaccuracies and a False Sense of Feminism in Disney’s Pocahontas In 1995, following the hugely financial success of The Lion King, which earned Disney close to one billion is revenue, Walt Disney Studios was slated to release a slightly more experimental story (The Lion King). Previously, many of the feature- length films had been based on fairy tales and other fictional stories and characters. However, over a Thanksgiving dinner in 1990 director Mike Gabriel began thinking about the story of Pocahontas (Rebello 15). As the legend goes, Pocahontas was the daughter of a highly respected chief and saved the life of an English settler, John Smith, when her father sought out to kill him. Gabriel began setting to work to create the stage for Disney’s first film featuring historical events and names and hoped to create a strong female lead in Pocahontas. The film would be the thirty-third feature length film from the studio and the first to feature a woman of color in the lead. The project had a lot of pressure to be a financial success after the booming success of The Lion King but also had the added pressure from director Gabriel to get the story right (Rebello 15). The film centers on Pocahontas, the daughter of the powerful Indian chief, Powhatan. When settlers from the Virginia Company arrive their leader John Smith sees it as an adventure and soon he finds himself in the wild and comes across Pocahontas. -

An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films Heidi Tilney Kramer University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2013 Monsters Under the Bed: An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films Heidi Tilney Kramer University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Kramer, Heidi Tilney, "Monsters Under the Bed: An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films" (2013). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4525 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Monsters Under the Bed: An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films by Heidi Tilney Kramer A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Women’s and Gender Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Elizabeth Bell, Ph.D. David Payne, Ph. D. Kim Golombisky, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 26, 2013 Keywords: children, animation, violence, nationalism, militarism Copyright © 2013, Heidi Tilney Kramer TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................................................................................ii Chapter One: Monsters Under -

How "The Lion King" Remake Is Different from the Animated Version by USA Today, Adapted by Newsela Staff on 07.29.19 Word Count 854 Level MAX

How "The Lion King" remake is different from the animated version By USA Today, adapted by Newsela staff on 07.29.19 Word Count 854 Level MAX Image 1. Mufasa (left) and Simba in a scene from Disney's animated "The Lion King" which was released in 1994. Photo by: Disney Studios How does Disney tell the story of a lion becoming king in 2019? Well, largely the same way it did in 1994. This time the movie studio is using photorealistic computer-generated imagery (CGI). Jon Favreau's remake of "The Lion King" (in theaters since July 19) brings Simba, Nala, Scar and the whole pride back to the big screen with new voice talent but much of the original plot intact. Fans of the animated classic get those moments they love: Simba's sneeze, the cub's presentation to the kingdom, Timon and Pumbaa's vulture-kicking entrance. Even much of the dialogue is identical to that of the 25-year-old movie. But there are some changes that add a half-hour of running time to the story. Here are a few notable updates, aside from the obvious fact that the animals no longer look like cartoons. Be prepared for a different version of Scar's sinister song, and for new Beyoncé music. This time, Scar (Chiwetel Ejiofor) doesn't so much croon "Be Prepared" as deliver his signature song like a dark, militaristic monologue. In place of a catchy chorus and humorous digs at hyenas This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. -

A Greener Disney Cidalia Pina

Undergraduate Review Volume 9 Article 35 2013 A Greener Disney Cidalia Pina Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/undergrad_rev Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Pina, Cidalia (2013). A Greener Disney. Undergraduate Review, 9, 177-181. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/undergrad_rev/vol9/iss1/35 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Copyright © 2013 Cidalia Pina A Greener Disney CIDALIA PINA Cidalia Pina is a isney brings nature and environmental issues to the forefront with its Geography major non-confrontational approach to programming meant for children. This opportunity raises awareness and is relevant to growing with a minor in environmental concerns. However this awareness is just a cursory Earth Sciences with Dstart, there is an imbalance in their message and effort with that of their carbon an Environmental footprint. The important eco-messages that Disney presents are buried in fantasy and unrealistic plots. As an entertainment giant with the world held magically concentration. This essay was captive, Disney can do more, both in filmmaking and as a corporation, to facilitate completed as the final paper for Dr. a greener planet. James Bohn’s seminar course: The “Disney is a market driven company whose animated films have dealt with nature Walt Disney Company and Music. in a variety of ways, but often reflect contemporary concerns, representations, and Cidalia learned an invaluable amount shifting consciousness about the environment and nature.” - Wynn Yarbrough, about the writing and research University of the District of Columbia process from Dr. -

ACCENTS and STEREOTYPES in ANIMATED FILMS the Case of Zootopia (2016)

Lingue e Linguaggi Lingue Linguaggi 40 (2020), 361-378 ISSN 2239-0367, e-ISSN 2239-0359 DOI 10.1285/i22390359v40p361 http://siba-ese.unisalento.it, © 2020 Università del Salento This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 ACCENTS AND STEREOTYPES IN ANIMATED FILMS The case of Zootopia (2016) LUCA VALLERIANI UNIVERSITÀ DI ROMA “LA SAPIENZA” Abstract – Language variation is an extremely useful tool to convey information about a character, even when this means playing with stereotypes, which are often associated to some dialects and sociolects (Lippi-Green 1997). Accents generally bear a specific social meaning within the cultural environment of the source text, this being the main reason why they are often particularly difficult to translate with varieties of the target language, even though there are several cases where this strategy proved to be a valid choice, especially in animation (Ranzato 2010). Building on previous research on the language of cartoons (Lippi-Green 1997, but also more recently Bruti 2009, Minutella 2016, Parini 2019), this study is aimed at exploring language variation and how this is deeply connected to cultural stereotypes in the animated Disney film Zootopia (Howard et al. 2016). After giving an outline of the social and regional varieties of American English found in the original version (Beaudine et al. 2017; Crewe 2017; Soares 2017) a special focus will be given to the Italian adaptation of the film through the analysis of the strategies chosen by adapters to render a similar varied sociolinguistic situation in Italian, with particular interest in the correspondence between language and stereotype. -

WHY NEMO MATTERS: ALTRUISM in AMERICAN ANIMATION by DAVID

WHY NEMO MATTERS: ALTRUISM IN AMERICAN ANIMATION by DAVID W. WESTFALL B.A., Pittsburg State University, 2007 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Social Work College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2009 Approved by: Major Professor Dr. L. Susan Williams Copyright DAVID W. WESTFALL 2009 Abstract This study builds on a small but growing field of scholarship, arguing that certain non- normative behavior is also non-negative, a concept referred to as positive deviance. This thesis examines positive behaviors, in the form of altruism, in the top 10 box-office animated movies of all time. Historically, studies focusing on negative, violent, and criminal behaviors garner much attention. Media violence is targeted as a cause for increasing violence, aggression, and antisocial behavior in youth; thousands of studies demonstrate that media violence especially influences children, a vulnerable group. Virtually no studies address the use of positive deviance in children’s movies. Using quantitative and ethnographic analysis, this paper yields three important findings. 1. Positive behaviors, in the form of altruism, are liberally displayed in children’s animated movies. 2. Altruism does not align perfectly with group loyalty. 3. Risk of life is used as a tool to portray altruism and is portrayed at critical, climactic, and memorable moments, specifically as movies draw to conclusion. Previous studies demonstrate that children are especially susceptible to both negativity and optimistic biases, underscoring the importance of messages portrayed in children’s movies. This study recommends that scholars and moviemakers consciously address the appearance and timing of positive deviance. -

Real Life Locations That Inspired the Lion King Rekero

The real landscapes that inspired the Lion King – and 10 amazing ways to see them 2019/08/04, 18*46 Telegraph Travel’s safari expert Brian Jackman on the Kenyan plains which inspired Disney’s writers, his own fascinating lion encounters, and ten of the best lodges in Africa to have yours Why should lions have held the world in thrall since the dawn of history? As long ago as the seventh century BC, the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal had his royal palace at Nineveh decorated with magnificent bas-reliefs of lion-hunting scenes. In Ancient Rome, the walls of the Colosseum resonated to the roars of lions as gladiators fought to the death with the king of beasts. Closer to our own time, Sir Edwin Landseer’s four bronze lions were set to guard the statue of Nelson, the nation’s hero in Trafalgar Square, and even in my lifetime I have watched spear-carrying Maasai warriors loping over the savannah to prove their manhood on a ceremonial lion hunt. Celebrated in literature by the likes of Ernest Hemingway and Karen Blixen, lions have maintained their enduring hold on the national psyche, appearing on the shirts of the England football team and even entering our living rooms thanks to the popularity of TV wildlife documentaries such as The Big Cat Diary and Sir David Attenborough’s Dynasties series. But not since Born Free, Joy Adamson’s true-life saga of Elsa – the lioness she raised and returned to the wild – has anything gripped the public imagination like The Lion King.