The Emergence and Transformation of Tigrayan Nationalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Abstract of the Thesis Of

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Micknai Arefaine for the degree of Master of Arts in Applied Anthropology presented on June 6, 2019. Title: Injera in the Kapitalocene: Understanding Women’s Perceptions of Change in Mekelle, Ethiopia Abstract approved: ______________________________________________________ Kenneth Maes Women’s lives in one of the oldest neighborhoods in Mekele, Ethiopia are very organized, systematic, and sophisticated. The women in this study model, express, and reflect the values of community, trust, care, stability, and futurity through their perceptions and sentiments regarding social and political change. I document how these values are reflected in their social reproduction and protection of injera as a staple of Ethiopian cuisine. The preparation of injera occurs in a sacred and gendered spatio-temporal location that is only accessible to women and children, and hopefully, in some small way, the readers of this thesis. This research serves to examine the micropolitics of everyday life as it occurs between women. Injera Epistemology is an emergent theoretical framework inspired in part by the work of Meredith Abarca, Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney, and Shawn Wilson. I use this framework to situate three women’s stories within the grander narrative of women’s empowerment in Ethiopia and beyond. ©Copyright by Micknai Arefaine June 6, 2019 All Rights Reserved Injera in the Kapitalocene: Understanding Women’s Perceptions of Change in Mekelle, Ethiopia by Micknai Arefaine A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Presented June 6, 2019 Commencement June 2020 Master of Arts thesis of Micknai Arefaine presented on June 6, 2019. -

20210714 Access Snapshot- Tigray Region June 2021 V2

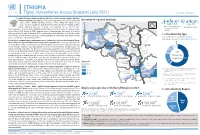

ETHIOPIA Tigray: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (July 2021) As of 31 July 2021 The conflict in Tigray continues despite the unilateral ceasefire announced by the Ethiopian Federal Government on 28 June, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Ethiopian National Overview of reported incidents July Since Nov July Since Nov Defense Forces (ENDF) and Eritrea’s Defense Forces (ErDF) from Tigray. In July, Tigray forces (TF) engaged in a military offensive in boundary areas of Amhara and Afar ERITREA 13 153 2 14 regions, displacing thousands of people and impacting access into the area. #Incidents impacting Aid workers killed Federal authorities announced the mobilization of armed forces from other regions. The Amhara region the security of aid Tahtay North workers Special Forces (ASF), backed by ENDF, maintain control of Western zone, with reports of a military Adiyabo Setit Humera Western build-up on both sides of the Tekezi river. ErDF are reportedly positioned in border areas of Eritrea and in SUDAN Kafta Humera Indasilassie % of incidents by type some kebeles in North-Western and Eastern zones. Thousands of people have been displaced from town Central Eastern these areas into Shire city, North-Western zone. In line with the Access Monitoring and Western Korarit https://bit.ly/3vcab7e May Reporting Framework: Electricity, telecommunications, and banking services continue to be disconnected throughout Tigray, Gaba Wukro Welkait TIGRAY 2% while commercial cargo and flights into the region remain suspended. This is having a major impact on Tselemti Abi Adi town May Tsebri relief operations. Partners are having to scale down operations and reduce movements due to the lack Dansha town town Mekelle AFAR 4% of fuel. -

519 Ethiopia Report With

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R Ethiopia: A New Start? T • ETHIOPIA: A NEW START? AN MRG INTERNATIONAL REPORT AN MRG INTERNATIONAL BY KJETIL TRONVOLL ETHIOPIA: A NEW START? Acknowledgements Minority Rights Group International (MRG) gratefully © Minority Rights Group 2000 acknowledges the support of Bilance, Community Aid All rights reserved Abroad, Dan Church Aid, Government of Norway, ICCO Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non- and all other organizations and individuals who gave commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for com- financial and other assistance for this Report. mercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. For further information please contact MRG. This Report has been commissioned and is published by A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the ISBN 1 897 693 33 8 issue which forms its subject. The text and views of the ISSN 0305 6252 author do not necessarily represent, in every detail and in Published April 2000 all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. Typset by Texture Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. MRG is grateful to all the staff and independent expert readers who contributed to this Report, in particular Tadesse Tafesse (Programme Coordinator) and Katrina Payne (Reports Editor). THE AUTHOR KJETIL TRONVOLL is a Research Fellow and Horn of Ethiopian elections for the Constituent Assembly in 1994, Africa Programme Director at the Norwegian Institute of and the Federal and Regional Assemblies in 1995. -

0150600020 ^S^R

Représentât! 0150600020 Reçu CLT CIH ITH ICH-02 - Form Le ' 2 1 SEP. United Nations . Intangible Educational, Scientific and . Cultural Cultural Organization . Héritage N0........... ^<-.. REPRESENTATIVE LIST 0F THE TANGIBLE CULTURAL HERITAGE 0F HUMA ITY Deadline 31 March 2020 for possible inscription in 2021 Instructions for completing thé nomination form are available at: htt s://ich. unesco. or /en/forms Nominations not complying with those instructions and those found below will be considered incomplète and cannot be accepted. A. State(s) Party(ies) For multinational nominations, States Parties should be listed in thé order on which they hâve mutually agreed. Ethiopia B. Name of thé élément B.1. Name of thé élément in English or French Indicatethé officiai name of thé élémentthat will appearin published matehal. Not to exceed 200 characters Ashenda, Ashendye, Aynewari, Maria, Shadey, Solel - Ethiopian Girls' Festival B.2. Name of thé élément in thé language and script of thé community concerned, if applicable Indicate thé officiai name of thé élément in thé vernacular language corresponding to thé officiai name in English or French (point B. 1). Not to exceed 200 characters l\m^. hî^^^!\^ïcPôs-a1Cf^S. y.^^-<!h.:t-^f 6^^^f- h-fl^ na,A B.3. Other name(s) of thé élément, if any In addition to thé officiai name(s) of thé élément(point B.1), mention alternate name(s), if any, by which thé élémentis known. In addition to thé officiai name of thé élément mentioned at point B2, thé festival is known by other alternate names among différent towns, cities, nations and nationalities of Northern Ethiopia. -

Modeling Malaria Cases Associated with Environmental Risk Factors in Ethiopia Using Geographically Weighted Regression

MODELING MALARIA CASES ASSOCIATED WITH ENVIRONMENTAL RISK FACTORS IN ETHIOPIA USING GEOGRAPHICALLY WEIGHTED REGRESSION Berhanu Berga Dadi i MODELING MALARIA CASES ASSOCIATED WITH ENVIRONMENTAL RISK FACTORS IN ETHIOPIA USING THE GEOGRAPHICALLY WEIGHTED REGRESSION MODEL, 2015-2016 Dissertation supervised by Dr.Jorge Mateu Mahiques,PhD Professor, Department of Mathematics University of Jaume I Castellon, Spain Ana Cristina Costa, PhD Professor, Nova Information Management School University of Nova Lisbon, Portugal Pablo Juan Verdoy, PhD Professor, Department of Mathematics University of Jaume I Castellon, Spain March 2020 ii DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I declare that the work described in this document is my own and not from someone else. All the assistance I have received from other people is duly acknowledged, and all the sources (published or not published) referenced. This work has not been previously evaluated or submitted to the University of Jaume I Castellon, Spain, or elsewhere. Castellon, 30th Feburaury 2020 Berhanu Berga Dadi iii Acknowledgments Before and above anything, I want to thank our Lord Jesus Christ, Son of GOD, for his blessing and protection to all of us to live. I want to thank also all consortium of Erasmus Mundus Master's program in Geospatial Technologies for their financial and material support during all period of my study. Grateful acknowledgment expressed to Supervisors: Prof.Dr.Jorge Mateu Mahiques, Universitat Jaume I(UJI), Prof.Dr.Ana Cristina Costa, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa, and Prof.Dr.Pablo Juan Verdoy, Universitat Jaume I(UJI) for their immense support, outstanding guidance, encouragement and helpful comments throughout my thesis work. Finally, but not least, I would like to thank my lovely wife, Workababa Bekele, and beloved daughter Loise Berhanu and son Nethan Berhanu for their patience, inspiration, and understanding during the entire period of my study. -

Amhara Claim of Western and Southern Parts of Tigray

AMHARA CLAIM OF WESTERN AND SOUTHERN PARTS OF TIGRAY By Mathza 11-26-20 We have been hearing and reading about the Amhara Regional State claim of ownership of the Welqayit, Tsegede, Qafta-Humera and Tselemti weredas (hereafter refereed to Welqayit Group) and Raya, and Amhara Regional State threats of war against TPLF/Tigray. One of the threats states “some of the Amhara elite politicians continue to beat drums, as summons to war” (watch/listen) DW TV (Amharic) - July 30, 2020. THE WELQAYIT GROUP Welkayit Amhara Identity Committee (WAIC) was formed in Gonder to return the Welqayit Group from Tigray Regional State to Amhara Regional State. The Welqayit Group was transferred to Tigray during the 1984 reconfiguration of the administrative structure of the country based on ethno-linguistical regional states (kililoch) after the Derg was defeated. It seems that the government of Eritrea has contributed to the Welqayit Group problem. According to ህግደፍንኣሸበርቲ ጉጅለታትን ብአንደበት…ቀዳማይ ክፋል (watch) the Eritrean government had trained Ethiopian oppositions and inculcated opposing views between ethnic groups in Ethiopia, particularly between Amhara and Tigray Regional States, wherever it viewed appropriate for its devilish objective of dismantling Ethiopia. The Committee recruited Tigrayans from Tigray Regional State to do its dirty work. An example is presented in a video, Tigrai Tv:መድረኽተሃድሶ ወረዳ ቃፍታ- ሑመራህዝቢ ጣብያ ዓዲ-ሕርዲ - YouTube (watch) aired on Feb 01, 2017. It shows confessions by a number of Tigrayans from Qafta-Humera who were lured and bribed by the Committee to serve its objectives. Each of them gave details of activities they participated in and carried out against their own people. -

Ethiopia: Ethnic Federalism and Its Discontents

ETHIOPIA: ETHNIC FEDERALISM AND ITS DISCONTENTS Africa Report N°153 – 4 September 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. FEDERALISING THE POLITY..................................................................................... 2 A. THE IMPERIAL PERIOD (-1974) ....................................................................................................2 B. THE DERG (1974-1991)...............................................................................................................3 C. FROM THE TRANSITIONAL GOVERNMENT TO THE FEDERAL DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC (1991-1994)...............................................................................................................4 III. STATE-LED DEMOCRATISATION............................................................................. 5 A. AUTHORITARIAN LEGACIES .........................................................................................................6 B. EVOLUTION OF MULTIPARTY POLITICS ........................................................................................7 1. Elections without competition .....................................................................................................7 2. The 2005 elections .......................................................................................................................8 -

Ethiopia COI Compilation

BEREICH | EVENTL. ABTEILUNG | WWW.ROTESKREUZ.AT ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation Ethiopia: COI Compilation November 2019 This report serves the specific purpose of collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. It is not intended to be a general report on human rights conditions. The report is prepared within a specified time frame on the basis of publicly available documents as well as information provided by experts. All sources are cited and fully referenced. This report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Every effort has been made to compile information from reliable sources; users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. © Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD An electronic version of this report is available on www.ecoi.net. Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD Wiedner Hauptstraße 32 A- 1040 Vienna, Austria Phone: +43 1 58 900 – 582 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.redcross.at/accord This report was commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 4 1 Background information ......................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Geographical information .................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1 Map of Ethiopia ........................................................................................................... -

Report on the Nexus Humera Case Study in Ethiopia

Report on the Nexus Humera case study in Ethiopia Dutch Climate Solutions research programme ECN-E--18-020 - March 2018 www.ecn.nl Report on the Nexus Humera case study in Ethiopia Author(s) Disclaimer Arend Jan van Bodegom - Wageningen Centre for Although the information contained in this document is derived from Development Innovation, Wageningen University & Research reliable sources and reasonable care has been taken in the compiling of Eskedar Gebremedhin - Deltares this document, ECN cannot be held responsible by the user for any errors, inaccuracies and/or omissions contained therein, regardless of the cause, Nico van der Linden - Energy research Centre of the nor can ECN be held responsible for any damages that may result Netherlands (ECN) therefrom. Any use that is made of the information contained in this Nico Rozemeijer - Wageningen Centre for Development document and decisions made by the user on the basis of this information Innovation, Wageningen University & Research are for the account and risk of the user. In no event shall ECN, its managers, directors and/or employees have any liability for indirect, non- Jan Verhagen - Wageningen University & Research material or consequential damages, including loss of profit or revenue and loss of contracts or orders. In co-operation with Page 2 of 67 ECN-E--18-020 Preface This report is deliverable D26 of the Dutch Climate Solutions research programme. The programme acts as a platform for the Energy research Centre of the Netherlands (ECN) to support the Netherlands Directorate-General for International Cooperation (DGIS) in the realisation of Dutch policy objectives concerning poverty reduction and sustainable development. -

Assessment of Promotional Mixes Practice of Tigray Tourism Industry, Ethiopia

GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites Year XIV, vol. 36, no. 2spl, 2021, p.597-602 ISSN 2065-1198, E-ISSN 2065-0817 DOI 10.30892/gtg.362spl06-688 ASSESSMENT OF PROMOTIONAL MIXES PRACTICE OF TIGRAY TOURISM INDUSTRY, ETHIOPIA Demoz AREFAYNE* Aksum University, Department of Management, Ethiopia, e-mail: [email protected] Leake LEGESSE Aksum University, Department of Marketing Management, Ethiopia, e-mail: [email protected] Daniel ALEMSHET Aksum University, Department of Tourism Management, Ethiopia, e-mail: daniofaxum@gmail. com Citation: Arefayne, D., Legesse, L., & Alemshet, D. (2021). ASSESSMENT OF PROMOTIONAL MIXES PRACTICE OF TIGRAY TOURISM INDUSTRY, ETHIOPIA. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 36(2spl), 597–602. https://doi.org/10.30892/gtg.362spl06-688 Abstract: Tigray Regional State has significant tourism potentials. However, it is unable to exploit the existing tourism products using a promotional strategy. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to assess the promotional practice of the Tourism industry. This study applied a quantitative study design. The data was collected from 180 foreign and domestic tourists. The findings of the study indicated that Tigray tourism office frequently used television and radio promotional Media which are the most traditional, but infrequently used modern promotional tools (Websites, Short Mobile Messages (SMS), word of mouth, public relation). Sales Promotion and Public Relations mixes are mostly applied promotional elements in Tigray tourism sites. Key words: Tourism, Promotional mix, Marketing mixes, Tigray, Ethiopia * * * * * * INTRODUCTION Tourism is an ever expanding service industry with latent vast growth potential and has become one of the largest and dynamically developing sectors of nations (Nurhssen, 2016). Therefore, observably in most developed countries, the smokeless industry has the lion's share in the overall economic growth and development of a country. -

Eastern Sudan Border

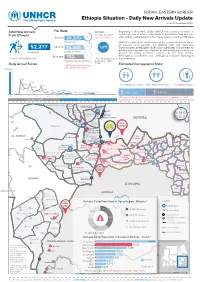

SUDAN: EASTERN BORDER Ethiopia Situation - Daily New Arrivals Update as of 20 December 2020 Total New Arrivals Per State Arrivals Beginning of November 2020, UNHCR has recorded an influx of From Ethiopia average per day asylum seekers at border entry points in East Sudan from Ethiopia, Kassala 36,370 70% (since 10th Nov) after military confrontations in the Tigray region in northern Ethiopia. (Hamdayet) UNHCR's teams at the border areas of the eastern Sudanese states 29% of Kassala and Gedaref are working with the Sudanese 52,277 Gedaref 15,205 1,271 Commissioner of Refugees (CoR), local authorities and partners to (Ludgi, Abdera) monitor and respond to the situation, as well mobilizing resources to Individuals provide life-saving assistance services to the new arrivals. Blue Nile 1% Inter-agency coordination and contingency response planning is Since 7th of November 2020. 702 2 Arrivals average since well underway. (Algazira, Yagolo, Yabisher) beginning of Nov 1,188. Daily Arrival Trends 20,572 Arrivals have been Estimated Demographic Data relocated to Um Rakuba . 45,689 6,815 5,228 4,394 3,813 31% Children (0 - 17 yrs) 64% Adults (18-59 yrs) 5% Elderly (+60 yrs) 2,976 3,094 1,640 2,683 2,253 740 844 439 1,144410 122 166 167 256 326 439 444 36% Female 64% Male 4 5 146 1,315 Nov 10 15 20 30 05 10 15 20 30 2020 25 25 Population distribution statistics are based on the ongoing household November | 2020 December | 2020 registration (11,000 HH) conducted by UNHCR and COR at registration centers. -

List of Panels for ICES20

List of Panels for ICES20 01 Archaeology, Paleoanthropology & Heritage 0101 Inter-Disciplinary Interconnections for the Scientific Growth of Ethiopian Archaeology 0102 Practices of Archaeological Researches and Conservation of Archaeological Sites in Ethiopia 0103 The Aksumite Ceramics to Reconstruct Social and Trade Intra-Interconnections The Foreign Projects Meet the Ethiopian Universities. Several Cases of Studies in Ethnology, 0104 Ethnography, Linguistics, Archaeology, and Experimental Researches. 0199 Archaeology, Paleoanthropology & Heritage – General Panel 02 Arts & Architecture Contemporary Ethiopian Art Scene: Drawing Heritages from the Past, and (Being Engaged in) New 0201 Aspects in Art 0202 Ethiopian Christian Art: Defining Styles, Defying Definitions 0203 Ethiopia's ecclesiastical painting traditions: influences, development, technology, and conservation 0204 Ethnomusicology Studies in Ethiopia 0205 Multifaceted Customs and Cultures of Ashenda, Ayniwari, Shadey, Solel 0206 Museums and Development in Ethiopia 0207 Music and the Dynamics of Contact in Ethiopia 0208 Musical Instruments and Performance of Peripheral Societies of Ethiopia Personal Adornment in Ethiopia: Regional and Global Influences on Local, Regional and National 0209 Dress, Jewelry and Tattoo/Body Painting. 0210 The New Rock-Hewn Churches of Ethiopia: Continuity or Revival? 0211 Traditional Building Technology and Comparison with Abroad 0212 Transnational Entanglements of Cultural Festivals in Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa “Art History, Church Architecture, Liturgical Development and Historical Issues in Tigray”: Inter- 0213 Disciplinary Researches 0299 Arts & Architecture – General Panel 03 Economics & Development Studies 0301 Ch’at in Ethiopia 0302 Development and Aid: From Conceptualisation to Implementation. 0303 Development and Labour on the Horn: Outlining the Contours of a Key Relationship 0304 Enabling Infrastructures, Redefining Territories: Ethiopia’s Regions Beyond Rural or Urban Bias Lands of the Future.