Volumen 5, Número 1, Enero-Junio, 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baku News and Events May 2013

Baku News and Events May 2013 Hungarian WizzAir Company will launch Budapest-Baku-Budapest flights - Nijat Mustafayev - APA The Hungarian WizzAir Company will launch a Budapest-Baku-Budapest flight on June 17, 2013, said the WizzAir’s Director Gyorgy Abran. According to him, ticket sales have already begun: “The flights from Budapest to Baku will be implemented on Mondays and Fridays at 20:35 (local time) and from Baku to Budapest – on Tuesdays and Saturdays at 03:55.” Abran noted that the Air Company has 40 Airbus A-320 aircrafts and the company will increase the number of aircrafts to 45 this year. For the present, the company has flights on more than 270 routes (33 countries). It carried 12 million passengers last year and this year is expected to reach 13.5 million. It is well known for flying all over Europe to 89 destinations including Warsaw, Barcelona, Frankfurt, Riga, and London. The current price is 120-150 euro from Baku to Budapest. Baku Charity Triathlon The 9th annual Baku Charity Triathlon will take place on Saturday, June 8, 2013. The race is a sprint-distance triathlon: 500m swim, 20km bike, 5 km run. The swim will take place at the Hyatt Oasis Club indoor pool during the morning, while the afternoon bike and run will take place at Stonepay Royal Park. The categories are an Open Race (men and women), an over 40’s race (men and women), an over 50s race (men and women) and two team races – teams of two or teams of three (no gender difference here). -

Esi Document Id 128.Pdf

Generation Facebook in Baku Adnan, Emin and the Future of Dissent in Azerbaijan Berlin – Istanbul 15 March 2011 “... they know from their own experience in 1968, and from the Polish experience in 1980-1981, how suddenly a society that seems atomized, apathetic and broken can be transformed into an articulate, united civil society. How private opinion can become public opinion. How a nation can stand on its feet again. And for this they are working and waiting, under the ice.” Timothy Garton Ash about Charter 77 in communist Czechoslovakia, February 1984 “How come our nation has been able to transcend the dilemma so typical of defeated societies, the hopeless choice between servility and despair?” Adam Michnik, Letter from the Gdansk Prison, July 1985 Table of contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... I Cast of Characters .......................................................................................................................... II 1. BIRTHDAY FLOWERS ........................................................................................................ 1 2. A NEW GENERATION ......................................................................................................... 4 A. Birth of a nation .............................................................................................................. 4 B. How (not) to make a revolution ..................................................................................... -

3 0 J Une 2 0

BAKU - AZERBAIJAN GUIDE to CULTURAL ENTERTAINMENTS since 2007 BAKU - AZERBAIJAN GUIDE to CULTURAL ENTERTAINMENTS since 2007 What & Where 1 - 3 0 J u n e 2 0 1 3 BAKU - AZERBAIJAN GUIDE to CULTURAL ENTERTAINMENTS since 2007 Uzeyir Hajibeyli Home-Museum Museum of Modern Art 69/69, Shamil Azizbeyov str., Baku 5, Yusif Safarov str., Baku Tel: (99412) 595 25 58 Tel: (99412) 490 84 84 (99412) 595 25 34 Opening hours: Opening hours: Tuesday-Sunday 10:00 – 18:00 11:00-21:00 Monday www.mim.az Jalil Mammadguluzade Home-Museum “Gallery 1969” 56, S. Taghiade str., Baku 27, Uz.Hajibeyli str., Baku Tel: (99412) 492 24 09 Tel: (994 12) 493 28 36 Opening hours: (994 12) 493 28 41 10:00 – 18:00 Opening hours: Tuesday-Sunday 10:00-18:00 Monday-Friday Nariman Narimanov Memorial Museum 35, Istiglaliyyat str., Baku Vajiha Samadova Exhibition Centre Tel: (99412) 492 05 15 19, Khagani str., Baku Opening hours: Tel: (99412) 493 62 30 09:00-18:00 (99412) 493 65 01 Monday-Sunday (99412) 493 17 44 (99412) 498 69 26 Mammad Said Ordubadi Memorial Museum Opening hours: 19/19, Khagani str., Baku 11:00-17:00 Tel: (99412) 493 50 85 Monday-Sunday Opening hours: 13:00-18:00 Boyuk Gala 19 Art Gallery Monday-Friday 19, Boyuk Gala str., Icherisheher, Baku Tel: (99412) 492 05 78 Hasan bey Zardabi Natural History Museum (99412) 493 05 01 3, Lermontov str., Baku Opening hours: Tel: (99412) 492 06 67 10:00 – 18:00 Opening hours: Tuesday-Sunday 10:00-17:00 Tuesday-Saturday Center of Azerbaijan Miniature Art 15, Gasr str., Icherisheher, Baku Jafar Jabbarli Home-Museum Tel: (99412) 492 59 06 44, S. -

IAUP Baku 2018 Semi-Annual Meeting

IAUP Baku 2018 Semi-Annual Meeting “Globalization and New Dimensions in Higher Education” 18-20th April, 2018 Venue: Fairmont Baku, Flame Towers Website: https://iaupasoiu.meetinghand.com/en/#home CONFERENCE PROGRAMME WEDNESDAY 18th April 2018 Fairmont Baku, Flame Towers 18:30 Registration 1A, Mehdi Hüseyn Street Fairmont Baku, Flame Towers, 19:00-21:00 Opening Cocktail Party Uzeyir Hajibeyov Ballroom, 19:05 Welcome speech by IAUP President Mr. Kakha Shengelia 19:10 Welcome speech by Ministry of Education representative 19:30 Opening Speech by Rector of ASOIU Mustafa Babanli THURSDAY 19th April 2018 Visit to Alley of Honor, Martyrs' Lane Meeting Point: Foyer in Fairmont 09:00 - 09:45 Hotel 10:00 - 10:15 Mr. Kakha Shengelia Nizami Ganjavi A Grand Ballroom, IAUP President Fairmont Baku 10:15 - 10:30 Mr. Ceyhun Bayramov Deputy Minister of Education of the Republic of Azerbaijan 10:30-10:45 Mr. Mikheil Chkhenkeli Minister of Education and Science of Georgia 10:45 - 11:00 Prof. Mustafa Babanli Rector of Azerbaijan State Oil and Industry University 11:00 - 11:30 Coffee Break Keynote 1: Modern approach to knowledge transfer: interdisciplinary 11:30 - 12:00 studies and creative thinking Speaker: Prof. Philippe Turek University of Strasbourg 12:00 - 13:00 Panel discussion 1 13:00 - 14:00 Lunch 14:00 - 15:30 Networking meeting of rectors and presidents 14:00– 16:00 Floor Presentation of Azerbaijani Universities (parallel to the networking meeting) 18:30 - 19:00 Transfer from Farimont Hotel to Buta Palace Small Hall, Buta Palace 19:00 - 22:00 Gala -

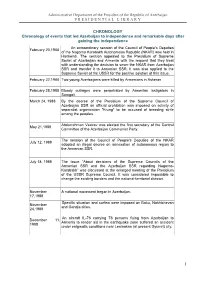

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I a L L I B R a R Y

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y CHRONOLOGY Chronology of events that led Azerbaijan to independence and remarkable days after gaining the independence An extraordinary session of the Council of People's Deputies February 20,1988 of the Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Republic (NKAR) was held in Hankendi. The session appealed to the Presidium of Supreme Soviet of Azerbaijan and Armenia with the request that they treat with understanding the decision to sever the NKAR from Azerbaijan SSR and transfer it to Armenian SSR. It was also applied to the Supreme Soviet of the USSR for the positive solution of this issue. February 22,1988 Two young Azerbaijanis were killed by Armenians in Askeran February 28,1988 Bloody outrages were perpetrated by Armenian instigators in Sumgait March 24, 1988 By the decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of Azerbaijan SSR an official prohibition was imposed on activity of separatist organization "Krung" to be accused of breeding strife among the peoples. Abdurrahman Vezirov was elected the first secretary of the Central May 21,1988 Committee of the Azerbaijan Communist Party. The session of the Council of People's Deputies of the NKAR July 12, 1988 adopted an illegal decree on annexation of autonomous region to the Armenian SSR. July 18, 1988 The issue “About decisions of the Supreme Councils of the Armenian SSR and the Azerbaijan SSR regarding Nagorno- Karabakh” was discussed at the enlarged meeting of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Council. -

Land of Music Festivals

Following tradition Azerbaijan – land of music festivals Lala HUSEYNOVA PhD in Arts THE LAND OF FIRE… AZERBAIJAN HAS BEEN KNOWN AS SUCH FROM TIME IMMEMORIAL, AND THERE ARE MANY REASONS FOR THAT. BUT WE WILL TALK ABOUT A COMPLETELY DIFFERENT FAME THAT THIS DEVELOPING AND FASCINATING LAND IS GRADUALLY EARNING ITSELF. THE LAND OF MUSIC FESTIVALS – tHIS IS HOW AZERBAIJAn’S CURRENT MUSICAL AND CUL- TURAL REALITIES CAN BE DESCRIBED IF WE WERE TO PARAPHRASE THE WELL-KNOWN PHRASE. least one traditional mu- sic festival is conducted in AtAzerbaijan every season. The participants and guests of the second “Space of Mugham” interna- tional festival, held over the spring holidays of Novruz (the first was held in 2009), are convinced that it was one of the most successful international projects on the traditional music of the East. This has largely been pos- sible thanks to the initiator and main sponsor of the festival, the Heydar Aliyev Foundation led by its President, the Goodwill Ambassador of UNESCO and ISESCO, Mehriban Aliyeva. As was the case during the first festival, the 34 www.irs-az.com Azerbaijan – land of music festivals capital Baku became a venue for a re- The festival was joined by vocalists the energy of life, but also the blos- cord number of music events for the and instrumentalists from Azerbaijan som of art and creative inspiration. eight days (14-21 March) of the festi- and foreign countries, including the The upcoming summer season is val. Art enthusiasts had the opportu- USA, Canada, France, Peru, Ecuador, promising to be no less interesting in nity to see the world’s first Mugham Turkey, Uzbekistan, Iran, Iraq, Egypt, terms of music events. -

Public Association for Assistance to Free Economy on Condition of Right

Public Association for Assistance to Free Economy On condition of right to property in 2011-2012 in Azerbaijan Authors: Ulviyya Asadzada Ziya Guliyev Editor: Zohrab Ismayil Corrector: Kamala Aghayeva Baku, Qanun Publication House, 2013 Funded by National Endowment for Democracy. CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS ECHR European Court of Human Rights PAAFE Public Union for Assistance to Free Economy OJSC Open Joint-Stock Company SOCAR State Oil Company of Azerbaijan Republic UN United Nations SSC State Statistics Committee SCPI State Committee on Property Issues PU Public Union EA Executive Authority PUHRE Public Union on Human Rights Education Ltd. Limited Liability Company HCPU Housing Communal Production Union Navy Naval Forces IPD Institute for Peace and Democracy Mass-media Mass-media 1. SUMMARY The research shows that the causes of the violations of property rights is not a sectoral. Such violations are due to many reasons. One of the main reasons behind the violation of the right to property is similar to other violations of law is itt’s inability to ensure rule of law, dependence of courts on executive structures, politically motivated decisions. İn this regard, attention is brought to the lack of independence of the judicial system of Azerbaijan, and the cases of corruption in the court system in a number of international reports. While analysing the cases of violation of the right to property, in 2011 it becomes evident that the courts have made decisions in favour of the executive authority structures instead of citizens. This decreases the belief of citizens toward the court, causes a situation as if they have “voluntarily” abandoned their properties and “gave up”. -

Privatization, State Militarization Through War, and Durable Social Exclusion in Post-Soviet Armenia Anna Martirosyan University of Missouri-St

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Dissertations UMSL Graduate Works 7-18-2014 Privatization, State Militarization through War, and Durable Social Exclusion in Post-Soviet Armenia Anna Martirosyan University of Missouri-St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Martirosyan, Anna, "Privatization, State Militarization through War, and Durable Social Exclusion in Post-Soviet Armenia" (2014). Dissertations. 234. https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation/234 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the UMSL Graduate Works at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Privatization, State Militarization through War, and Durable Social Exclusion in Post-Soviet Armenia Anna Martirosyan M.A., Political Science, University of Missouri - St. Louis, 2008 M.A., Public Policy Administration, University of Missouri - St. Louis, 2002 B.A., Teaching Foreign Languages, Vanadzor Teachers' Training Institute, Armenia, 1999 A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School at the University of Missouri - St. Louis in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science July 11, 2014 Advisory Committee David Robertson, Ph.D. (Chair) Eduardo Silva, Ph.D. Jean-Germain Gros, Ph.D. Kenneth Thomas, Ph.D. Gerard Libardian, Ph.D. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS i -

Institute for Reporters' Freedom and Safety Azerbaijan's Free

Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety Azerbaijan’s Free Expression Crackdown Intensifies in Run-up to Election 2013 Biannual Report on Freedom of Expression in Azerbaijan This report is made possible thanks to support from International Media Support (IMS). The opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the donor. IRFS is solely responsible for the analysis and recommendations contained herein. Cover photo: Obyektiv TV reporter, Rasim Aliyev was attacked by a police officer while filming a peaceful Baku protest in support of the Occupy Gezi protests in Turkey. June 03, Baku. © IRFS For more information visit: www.irfs.org or follow us on Twitter @IRFS_Azerbaijan 2 Contents 1. Introduction 1.1. Background 1.2. Objectives and focus 1.3. Methodology and structure 2. Recommendations 3. Chapter One: Violence, blackmail, and pressure against journalists 4. Chapter Two: Restrictions on privacy 5. Chapter Three: Legal repression of freedom of expression 6. Chapter Four: Detention of journalists, bloggers, and human rights defenders 7. Chapter Five: State control over the media 8. Chapter Six: Freedom of expression online 9. Conclusion 3 Introduction 1.1. Background This report is a publication of the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety (IRFS), an independent, non-profit organization dedicated to promoting freedom of expression in Azerbaijan. IRFS was founded on World Press Freedom Day in 2006 by two Azerbaijani journalists in response to growing restrictions by the government on freedom of expression and media freedom. The organization’s reporting has been instrumental in bringing freedom of expression issues in Azerbaijan to the attention of relevant organizations and officials in the United States and Europe. -

Dmitry Bertman Director

Dmitry Bertman Director Dmitry Bertman was born in Moscow and he graduated from the Russian Academy of Theatre Arts with a specialization in “Musical Theatre Stage Director” (training course of Professor G. Ansimov). Bertman is the People’s Artist of the Russian Federation (2005), three times winner of “Zolotaya Maska (Golden Mask)” National Theatre Award (1998, 1999, 2001), thrice winner of the Union of Theatre Workers’ Award “Gvozd Sezona” (2003, 2004, 2005), winner of Stanislavsky Prize (2005), Moscow City Government Prize (2007), State Prize of Estonia and the Prize of the Estonian Theatre Union (2008). He has been awarded the Order of Friendship, the Order of Academic Palms (Officer), the Maltese Cross, the Sovereign Military Order of Malta and the Order of the Cross of Terra Mariana. Being a student Dmitry Bertman put on a series of musical and drama performances plays in the theatres of Russia and Ukraine, and in 1990 he founded a musical theatre Helikon-Opera in Moscow, which was granted the status of a national theatre in 1993 and soon became one of the most famous Russian opera brands. The theatre is constantly on tour throughout Russia and abroad, cooperates with significant opera agencies and takes part in various festivals. Dmitry Bertman has staged over hundred performances, including a number of Russian and world premieres. Besides his persistent activities in Helikon-Opera, the theater director is also consistently involved in the work under the world opera projects. Bertman’s productions are on the stages of the Canadian -

101 26 January 2018

No. 101 26 January 2018 Abkhazia South Ossetia caucasus Adjara analytical digest Nagorno- Karabakh www.laender-analysen.de/cad www.css.ethz.ch/en/publications/cad.html URBANIZATION AND URBAN PUBLIC POLICY IN BAKU Special Editor: Farid Guliyev ■■Urban Planning in Baku: Who is Involved and How It Works 2 By Farid Guliyev, Baku ■■Baku’s Quest to Become a Major City: Did the Dubai Model Work? 9 By Anar Valiyev, Baku ■■A Clash of Cultures: How Rural Out-Migrants Adapt to Urban Life in Baku 11 By Turkhan Sadigov, Baku ■■Modernization of Baku’s Transport System: Infrastructure Development Issues 15 By Fuad Jafarli, Baku ■■Urban Redevelopment from the Bottom-Up: Strengths and Challenges of Grassroots Initiatives in Baku 19 By Nazaket Azimli, Baku Research Centre Center Center for Eastern European German Association for for East European Studies for Security Studies CRRC-Georgia East European Studies Studies University of Bremen ETH Zurich University of Zurich CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 101, 26 January 2018 2 Urban Planning in Baku: Who is Involved and How It Works By Farid Guliyev, Baku Abstract This article examines the urban governance system of Baku City with a focus on recent urban reconstruc- tion projects. First, I outline the mechanism of oil surplus recycling that underlies Baku’s recent construc- tion boom. Second, I explore the regulatory regime and the roles of different government agencies engaged in “implementation games”. City politics has thus turned into an arena for the neopatrimonial scramble for public resources. Baku’s urban policy decisions reflect the confluence of interests of bureaucratic patronage networks and oligarchic-business groups. -

City of Baku Goes Back to the Great Antiquity, Though the Exact Date of Its Rise Is Not Known up to Now

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y CAPITAL Contents General overview of Baku ...................................................................................................................... 2 Symbols of Baku city............................................................................................................................... 3 Flag of "Bacu" (Baku) in the Middle Ages .................................................................................................. 3 The emblem of Icheri sheher (the inner city) in the Middle ages .............................................................. 4 Baku’s first coats of arms .............................................................................................................................. 5 The emblem of Baku city at present ............................................................................................................. 6 History of Baku city Executive Power................................................................................................... 7 History of Baku ....................................................................................................................................... 8 On the etymology of the name “Baku” ........................................................................................................ 9 Antiquity ......................................................................................................................................................