Pediatric Palliative Care: Global Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tech Giant Everyone Is Watching

Inside Assad’s new Syria The Supreme Court swings right Cutting out medical mistakes How to make meetings less dreadful JUNE 30TH–JULY 6TH 2018 Thetechgiant everyone is watching “I keep pursuing new HIV/AIDS treatments which is why 29 years later, I’m still here.” Brian / HIV/AIDS Researcher James/HIV/AIDSPatient In the unrelenting push to defeat HIV/AIDS, scientists’ groundbreaking research with brave patients in trials has produced powerful combination antiretroviral treatments, reducing the death rate by 87% since they were introduced. Welcome to the future of medicine. For all of us. GoBoldly.com Contents The Economist June 30th 2018 5 7 The world this week Asia 32 Politics in the Philippines Leaders Rebel with a cause 11 Netflixonomics 33 Elections in Indonesia The tech giant everyone A 175m-man rehearsal is watching 33 South Korea’s baby bust 12 America’s Supreme Court Procreative struggle After Kennedy 34 Virginity tests in 12 The war in Syria South Asia The new Palestinians Legal assault US Supreme Court Justice 13 Railways 35 Banyan Anthony Kennedy’s retirement Free the rails Asia braces for a trade war comes at a worrying time: 14 China’s university- leader, page12. The 2017-18 On the cover entrance exam China term was a triumph for Netflix has transformed Gaokao gruel 36 Community management conservatives, page 21 television. It is beloved by Beefing up neighbourhood investors, consumers and Letters watch politicians. Can that last? 15 On trade, surveillance 37 University admissions Leader, page11. The technology, Xinjiang, The gaokao goes global entertainment industry is football, Brexit scrabbling to catch up with a disrupter, page18. -

Digital Migration in Africa

CHALLENGES AND PERSPECTIVES OF DIGITAL MIGRATION FOR AFRICAN MEDIA By Guy Berger CONTENTS CHALLENGES AND PERSPECTIVES OF DIGITAL MIGRATION FOR AFRICAN MEDIA 3 Contents 4 Preface 6 Executive Summary 8 Introduction ISBN 978086104621 11 Digital migration – definitions and issues First Edition Title: Challenges and Perspectives of Digital Migration for African Media 60 Author: Guy Berger Radio 2010 71 Television Panos Institute of West Africa Dakar, Senegal. www.panos-ao.org. 74 Awareness and preparation in Africa 6 rue Calmette, BP 21132 Dakar (Senegal) Tel: (221) 33. 849.16.66 Fax: (221) 33.822.17.61 81 Strategies in operation Highway Africa, African Media Matrix, Upper Prince Alfred Street Rhodes University Grahamstown, 6410 87 Recommendations to stakeholders South Africa Design and layout: Kaitlin Keet 92 Bibliography, Panos Institute West Africa [email protected] terms of reference for this study, List of Text editing and proofreading: Danika Marquis acronyms PREFACE Panos Institute West Africa (PIWA) has pleasure in welcoming this assist civil society and good governance. What will make such a booklet. It is work commissioned by PIWA in collaboration with positive difference is the way that law, policy and practice evolves. Rhodes University as a knowledge resource especially for those On the other side, uninformed policy, law and practice will reduce, working in community radio in Africa. rather than expand, the role of African media in informing the The publication takes a complex subject, digital migration, and peoples of the continent. seeks to explain it in language that non-experts can understand. This booklet aims to contribute to awareness-raising in West This accords with PIWA’s interests in spreading knowledge to Africa (and beyond), of the importance of digital migration and make a difference to media in West Africa as well as more broadly the need to create appropriate strategies in order to maximize around the continent. -

Community Television in Thailand

Community Television in Thailand Overview of ITU work 12 December 2017 Peter Walop International Telecommunication Union Agenda 1. Introduction to CTV 2. Country Case Studies Topics 3. Regulatory Framework for CTV 4. Trial for CTV services 2 1. Introduction to CTV • What is CTV and reports by ITU • CTV Value Chain • DTTB Distribution 3 1. Introduction CTV reports • Essential elements of CTV: 1. Community owned and controlled 2. Not‐for‐profit enterprise 3. Local or regional 4. Operated by volunteers • NBTC/ITU Project on “Development of a Framework for Deploying Community TV Broadcasting Services in Thailand” produced 3 reports: 1. Country Case Studies 2. Regulatory Framework for CTV services 3. Practical Guidelines for CTV Trail 4 1. Introduction to CTV Value chain • Content production (studio), contribution and distribution (delivery) • Different distribution platforms available: o Internet (including IPTV and OTT) o Cable (& Satellite DTH) o Digital Terrestrial Television Broadcasting (DTTB) • Sharing of facilities throughout the value chain Production Delivery Reception Presentation Acquisition Compression or Demodulation Display Post production Encoding Demultiplexing Quality Assessment Recording Assembling Disassembling Transmission Decompression Multiplexing Emission (modulation, frequency planning, service area) CTV broadcaster Network Operator At home/reception location 5 1. Introduction to CTV DTTB distribution • 5 multiplexes deployed (95% pop. coverage) • 6th multiplex designed for CTV in 39 Local Areas • In each Local Area: o Several sites (ranging from 2 to 12) o Up to 12 services • Total capacity of 6 th multiplex: 12 x 39 = 468 CTV services each DTTB site Mux 6 12SD 6 2. Country Case Studies • 8 countries: o Australia o Canada o France o Indonesia o South Africa o Netherlands o UK o USA 7 2. -

Sophie Toupin

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Paolo Bory, Gianluigi Negro, Gabriele Balbi u.a. (Hg.) Computer Network Histories. Hidden Streams from the Internet Past 2019 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/13576 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Teil eines Periodikums / periodical part Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Bory, Paolo; Negro, Gianluigi; Balbi, Gabriele (Hg.): Computer Network Histories. Hidden Streams from the Internet Past, Jg. 21 (2019). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/13576. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://doi.org/10.33057/chronos.1539 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0/ Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0/ License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ PAOLO BORY, GIANLUIGI NEGRO, GABRIELE BALBI (EDS.) COMPUTER NETWORK HISTORIES COMPUTER NETWORK HISTORIES HIDDEN STREAMS FROM THE INTERNET PAST Geschichte und Informatik / Histoire et Informatique Computer Network Histories Hidden Streams from the Internet Past EDS. Paolo Bory, Gianluigi Negro, Gabriele Balbi Revue Histoire et Informatique / Zeitschrift Geschichte und Informatik Volume / Band 21 2019 La revue Histoire et Informatique / Geschichte und Informatik est éditée depuis 1990 par l’Association Histoire et Informatique et publiée aux Editions Chronos. La revue édite des recueils d’articles sur les thèmes de recherche de l’association, souvent en relation directe avec des manifestations scientifiques. La coordination des publications et des articles est sous la responsabilité du comité de l’association. -

Health Professions Act: List of Approved Facilities for the Purposes

STAATSKOERANT, 16 OKTOBER 2013 No. 36936 39 No. 791 16 October 2013 HEALTH PROFESSIONS ACT, 1974 (ACT NO. 56 OF 1974) LIST OF APPROVED FACILITIES FOR THE PURPOSES OF PERFORMING COMMUNITY SERVICE BY MEDICAL PRACTITIONERS IN THE YEAR 2014 The Minister of Health has, in terms of regulation 5.1 of the Regulations relating to Performance of Community Service by Persons Registering in terms of the Health Professions Act, 1974 (Act No. 56 of 1974), listed the following approved facilities for purposes of the profession of medicine. PROVINCE REGION/DISTRICT FACILITY EASTERN CAPE Alfred Nzo Khotsong Hospital* Madzikane kaZulu Hospital ** Umzimvubu Cluster Mt Ayliff Hospital** Taylor Bequest Hospital* (Matatiele) Amathole Bhisho CHH Cathcart Hospital * Amahlathi/Buffalo City Cecilia Makiwane Hospital Cluster Dimbaza CHC Duncan Village Day Hospital Empilweni Gompo CHC Fort Grey TB Hospital Frere Hospital Grey Hospital * Komga Hospital Nkqubela TB Hospital Nompumelelo Hospital* SS Gida Hospital* Stutterheim FPA Hospital* Mnquma Sub-District Butterworth Hospital* Nqgamakwe CHC* Nkonkobe Sub-District Adelaide FPA Hospital Tower Hospital* Victoria Hospital * Mbashe /KSD District Elliotdale CHC* Idutywa CHC* Madwaleni Hospital* Chris Hani All Saints Hospital** Engcobo/IntsikaYethu Cofimvaba Hospital** Martjie Venter FPA Hospital This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za 40 No. 36936 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 16 OCTOBER 2013 Sub-District Mjanyana Hospital * InxubaYethembaSub-Cradock Hospital** Wilhelm Stahl Hospital** District Inkwanca -

March of Mobile Money: the Future of Lifestyle Management

The March of Mobile Money THE FUTURE OF LIFESTYLE MANAGEMENT SAM PITRODA & MEHUL DESAI The March of Mobile Money THE FUTURE OF LIFESTYLE MANAGEMENT SAM PITRODA & MEHUL DESAI First published in India in 2010 by Collins Business An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers a joint venture with The India Today Group Copyright © Sam Pitroda and Mehul Desai 2010 ISBN: 978-81-7223-865-0 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 Sam Pitroda and Mehul Desai assert the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. HarperCollins Publishers A-53, Sector 57, Noida 201301, India 77-85 Fulham Palace Road, London W6 8JB, United Kingdom Hazelton Lanes, 55 Avenue Road, Suite 2900, Toronto, Ontario M5R 3L2 and 1995 Markham Road, Scarborough, Ontario M1B 5M8, Canada 25 Ryde Road, Pymble, Sydney, NSW 2073, Australia 31 View Road, Glenfield, Auckland 10, New Zealand 10 East 53rd Street, New York NY 10022, USA Typeset in 12/18.3 Dante MT Std InoSoft Systems Printed and bound at Thomson Press (India) Ltd We would like to thank the entire C-SAM family and its well-wishers, without whom this journey would not be as enriching. We would like to thank Mayank Chhaya, without whom we would not have been able to complete this book. We would like to thank our better halves, Anu and Malavika, without whose companionship this journey and book would not be as meaningful. -

Presidency Expresses Shock As Police Move to Stop Judicial Inquiries

Excitement as New Diaspora Remittances Policy takes Effect Today Annual inflows put at $24bn CBN, NSIA, AFC to float N15tn infrastructure fund Ndubuisi Francis and James unhindered access to Diaspora take effect today. banks and the International He stated that as a result of become effective from Friday, Emejo in Abuja remittances takes effect today. He said following the Money Transfer Operators the CBN's engagements with December 4, 2020." The CBN Governor, Mr. announcement of the new (IMTOs) to ensure that major IMTOs and the DMBs Emefiele told journalists There is palpable excitement Godwin Emefiele, spoke policy measures, the apex recipients of remittance inflows yesterday, the stakeholders had in Abuja that the new policy among Forex users as the yesterday at a press conference bank, in an effort to enable are able to receive their funds committed that they would would help in providing a Central Bank of Nigeria’s in Abuja and said the policy smooth implementation had in the designated foreign deploy all the necessary tools (CBN) new policy that allows released last Monday would engaged with the commercial currency of their choice. to "ensure that these measures Continued on page 9 $21bn Legally Withdrawn from NLNG Dividends Account, Says Kyari... Page 8 Friday 4 December, 2020 Vol 25. No 9370. Price: N250 www.thisdaylive.com T RU N TH & REASO FG Dismisses Calls for Buhari’s Resignation as Cheap Politicking Insists president will serve out tenure Peter Uzoho Muhammadu Buhari to resign claims that Boko Haram The minister, at a security. members that the federal every time there is a setback fighters are collecting taxes meeting yesterday with the The meeting, which was government has been meeting The Minister of Information in the war against terror as a from the people, adding that Newspapers’ Proprietors convened at the instance with different stakeholders and Culture, Alhaji needless distraction and cheap the occupation of territories Association of Nigeria (NPAN) of the minister, was held at nationwide in the wake of Lai Mohammed, has politicking. -

Independent Communications Authority of South Africa Act: Inquiry

4 No. 41070 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 25 AUGUST 2017 GENERAL NOTICES • ALGEMENE KENNISGEWINGS Independent Communications Authority of South Africa/ Onafhanklike Kommunikasie-owerheid van Suid-Afrika INDEPENDENT COMMUNICATIONS AUTHORITY OF SOUTH AFRICA NOTICE 642 OF 2017 642 Independent Communications Authority of South Africa (13/2000): Invitation for written representations 41070 (r) O z 00 c oI-I n cn rn(f) zi-i -1 This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za STAATSKOERANT, 25 AUGUSTUS 2017 No. 41070 5 INVITATION INVITATION WRITTEN WRITTEN REPRESENTATIONS REPRESENTATIONS FOR FOR Authority Authority of terms terms of of of the the Independent Communications In In Section Section South South 4B 4B (Act (Act Africa Africa submit submit of of 2000), 2000), interested invited invited Act Act hereby hereby No No 13 to to persons persons are their their written written the the the the representations representations Document Document regarding Discussion Discussion Inquiry Inquiry on on Subscription Subscription Television herewith into into Broadcasting Broadcasting published the the Services Services by by Authority. Authority. of the the Document Document will available available made made Discussion Discussion A A be be the the copy copy on on Authority's Authority's the Authority's website website and and at at at Library Library in in Street, Street, Katherine Katherine (Ground (Ground 164 164 Pinmill Pinmill Floor Floor Block Farm, Farm, D), No. No. at at Sandton Sandton 16h00, 16h00, between between 09h00 Monday Monday Friday. and and to to Written Written representations with the the regard regard Document Document must to to Discussion Discussion be be Authority Authority submitted submitted later the the than than by by 16h00 16h00 October October 2017 31 31 to to post, post, by by on on no no delivery delivery electronically marked marked specifically Microsoft Microsoft Word) (in (in hand hand and and for for or or Refilwe Refilwe Pinmill Ramatlo. -

Monitoring and Evaluation Indicators of the HIV & AIDS Programme In

Monitoring and Evaluation Indicators of the HIV & AIDS programme in Grahamstown‘s public sector health care system A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF PHARMACY IN PHARMACY PRACTICE of RHODES UNIVERSITY by PHEHELLO ANTHONY MAHASELE January 2011 DEDICATION To the loving Memory of my Grandmother Makolone Masefora Augostina Mahasele 01 January 1919 – 22 May 2008 ii Abstract South Africa is one of the countries hardest hit with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Acquired Immuno Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) epidemic. In response to the epidemic, the South African government adopted the Comprehensive HIV & AIDS Care, Management and Treatment programme strategic plan (CCMT) in 2000 (1) and developed the Operational Plan for CCMT for antiretroviral therapy roll- out in 2003 (2). In order to monitor the progress of the implementation of CCMT, the National Department of Health (NDOH) adopted the Monitoring and Evaluation (M & E) framework in 2004 (3). The aim of this study was to assess the HIV & AIDS programme in Grahamstown‘s public sector health care system by using the national M & E indicators of the HIV & AIDS programme. The national M & E framework was used as the data collection tool and available information was collected from various sources such as the District Health Office (DHO), Primary Health Care (PHC) office, accredited antiretroviral sites and the provincial pharmaceutical depot. Group interviews were conducted with key stakeholder health care professionals at the District Health Office, Primary Health Care office, Settlers Hospital and the provincial Department of Health personnel. A one-on- one interview was conducted with the Deputy Director of HIV & AIDS Directorate, monitoring and evaluation in the National Department of Health. -

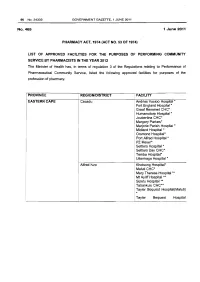

Health Professions Act: List of Approved Facilities for Community Service by Pharmacists in 2012

96 No.34332 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 1 JUNE 2011 No.465 1 June 2011 PHARMACY ACT, 1974 (ACT NO. 53 OF 1974} LIST OF APPROVED FACILITIES FOR THE PURPOSES OF PERFORMING COMMUNITY SERVICE BY PHARMACISTS IN THE YEAR 2012 The Minister of Health has, in terms of regulation 3 of the Regulations relating to Performance of Pharmaceutical Community Service, listed the following approved facilities for purposes of the profession of pharmacy. PROVINCE REGION/DISTRICT FACILITY EASTERN CAPE Cacadu Andries Vosloo Hospital * Fort England Hospital* Graaf Reneinet CHC* Humansdorp Hospital * Joubertina CHC* Margery Parkes* Marjorie Parish Hospital* Midland Hospital * Orsmond Hospital* Port Alfred Hospital * PZ Meyer* Settlers Hospital * Settlers Day CHC* Temba Hospital• Uitenhage Hospital * Alfred Nzo Khotsong Hospital• Maluti CHC* Mary Theresa Hospital .... ! Mt Ayliff Hospital ** · Sipetu Hospital •• Tabankulu CHC*• Tayler Bequest Hospitai(Maluti) * Tayler Bequest Hospital STAATSKOERANT, 1 JUNIE 2011 No. 34332 97 (Matatiele )"' Chris Hani All Saints Hospital ..... Cala Hospital ** Cofimvaba Hospital ** Cradock Hospital ** Elliot Hospital ... Frontier Hospital * Glen Grey Hospital * Mjanyana Hospital ** NgcoboCHC* Ngonyama CHC* Nomzamo CHC* Sada CHC* Thornhill CHC* Wilhelm Stahl Hospital ..... ZwelakheDalasile CHC* Nelson Mandala Dora Nginza Hospital Elizabeth Donkin Hospital Jose Pearson Santa Hospital Kwazakhele Day Clinic Laetitia Bam CH C Livingstone Hospital Motherwell CHC New Brighton CHC PE Pharmaceutical Depot PE Provincial Hospital Amathole Bedford Hospital Bhisho Hospital Butterworth Hospital Cecilia Makiwane Hospital Cathcart Hospital Dimbaza CHC Duncan Village Day CHC Dutywa CHC Empilweni Gompo CHC Fort Beauford Hospital Fort Grey Hospital Frere Hospital Grey Hospital Middledrift CHC Nontyatyambo CHC Nompomelelo Hospital Ngqamakwe CHC SS Gida Hospita Tafalofefe Hospital Tower Hospital Victoria Hospital Winterberg Hospital Willowvale CHC 98 No. -

Annual Report 2016

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 - 2017 This annual report of the Media Development and Diversity Agency (MDDA) describes and details the activities of the Agency for the period 1 April 2016 to 31 March 2017. This report has been prepared for submission to the Executive Authority and the Parliament of South Africa in line with the requirements of the Public Finance Management Act (No 1 of 1999) and the MDDA Act (No 14 of 2002). The Media Development and Diversity Agency (MDDA) is a statutory development agency for promoting and ensuring media development and diversity, set up as a partnership between the South African Government and major print and broadcasting companies to assist in (amongst others) developing community and small commercial media in South Africa. It was established in 2003, in terms of the MDDA Act No. 14 of 2002, and started providing grant funding to projects on 29 January 2004. MDDA ANNUAL REPORT 2016 - 2017 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Vision 4 PART ONE: INTRODUCTION 5 Mission 4 1.1 Minister of Communications Foreword 6 1.2 Chairperson’s Statement and Foreword 7 Values 4 1.3 Chief Executive Officer’s Executive Summary and Overview 2016/2017 10 MDDA Value Proposition 4 1.4 MDDA Board 15 Overall Objective 4 1.5 Mandate of the MDDA 18 Mandate 4 PART TWO: PERFORMANCE FOR 2016/2017 20 2.1 Service Delivery Environment 21 2.2 Performance Against Objectives 23 2.3 Summary of Projects Supported for the Financial Year 34 PART THREE: ENVIRONMENTAL LANDSCAPE AND FUNDING 61 3.1 Growth and Development of Local Media 62 3.2 Advertising Revenue 62 3.3 -

00 Evaluation of BDM Communication Strategy

Evaluation of Broadcasting Digital Migration Communication Strategy (Public Awareness Campaign and Consumer Support) Final Report Prepared for DoC by Pan Africa TMT Group 23 October 2017 Evaluation of BDM Communication Strategy This report has been independently prepared by Pan Africa TMT Group. The Evaluation Steering Committee comprises the Department of Communications and Department of Performance Monitoring and Evaluation in the Presidency. The Steering Committee oversaw the operation of the evaluation, commented and approved the reports. Submitted by: Submitted to: Pan Africa TMT Group Directorate: Strategic Planning and Performance Monitoring Technology | Media | Telecommunications The Department of Communications Tel: 011 886 0138 | Mobile: 061 499 3134 Tel: 012 473 0309 Tshedimosetso House, 1035 cnr Frances Baard 104 Atrium Terraces | 272 Oak Ave | Randburg and Festival streets, Hatfield, Pretoria E-Mail: [email protected] [email protected] Web: www.panafricatmt.com www.doc.gov.za DOCUMENT CONTROL SHEET CLIENT DoC Project Implementation Evaluation of the Broadcasting Digital Migration Communication Strategy (Public Awareness Campaign and Consumer Support) Document type Implementation Evaluation Report Title Evaluation of the Broadcasting Digital Migration Communication Strategy (Public Awareness Campaign and Consumer Support) Author(s) Khathu Netshisaulu, Hubert Matlou, Moloko Masipa, Malesela Kekana. Edited by Nomonde Gongxeka Seopa Document numBer DOC_EBDMCS_PATMT_2017 No Version Date Reviewed By 0.1 First Draft (content review) 2017-08-30 PATMT 0.2 Final Draft (for editing) 2017-09-15 PATMT & DOC (Steering Committee) 1.0 Final Report ( for Presentation) 2017-09-29 PATMT & Steering Committee & MANCO 1.1 Final Report ( for Submission) 2017-10-23 PATMT 2 Evaluation of BDM Communication Strategy Table of Contents Index of Figures ....................................................................................................................................