Monitoring and Evaluation Indicators of the HIV & AIDS Programme In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Professions Act: List of Approved Facilities for the Purposes

STAATSKOERANT, 16 OKTOBER 2013 No. 36936 39 No. 791 16 October 2013 HEALTH PROFESSIONS ACT, 1974 (ACT NO. 56 OF 1974) LIST OF APPROVED FACILITIES FOR THE PURPOSES OF PERFORMING COMMUNITY SERVICE BY MEDICAL PRACTITIONERS IN THE YEAR 2014 The Minister of Health has, in terms of regulation 5.1 of the Regulations relating to Performance of Community Service by Persons Registering in terms of the Health Professions Act, 1974 (Act No. 56 of 1974), listed the following approved facilities for purposes of the profession of medicine. PROVINCE REGION/DISTRICT FACILITY EASTERN CAPE Alfred Nzo Khotsong Hospital* Madzikane kaZulu Hospital ** Umzimvubu Cluster Mt Ayliff Hospital** Taylor Bequest Hospital* (Matatiele) Amathole Bhisho CHH Cathcart Hospital * Amahlathi/Buffalo City Cecilia Makiwane Hospital Cluster Dimbaza CHC Duncan Village Day Hospital Empilweni Gompo CHC Fort Grey TB Hospital Frere Hospital Grey Hospital * Komga Hospital Nkqubela TB Hospital Nompumelelo Hospital* SS Gida Hospital* Stutterheim FPA Hospital* Mnquma Sub-District Butterworth Hospital* Nqgamakwe CHC* Nkonkobe Sub-District Adelaide FPA Hospital Tower Hospital* Victoria Hospital * Mbashe /KSD District Elliotdale CHC* Idutywa CHC* Madwaleni Hospital* Chris Hani All Saints Hospital** Engcobo/IntsikaYethu Cofimvaba Hospital** Martjie Venter FPA Hospital This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za 40 No. 36936 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 16 OCTOBER 2013 Sub-District Mjanyana Hospital * InxubaYethembaSub-Cradock Hospital** Wilhelm Stahl Hospital** District Inkwanca -

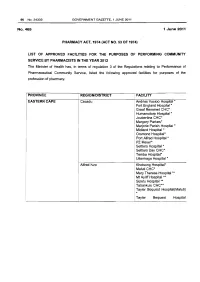

Health Professions Act: List of Approved Facilities for Community Service by Pharmacists in 2012

96 No.34332 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 1 JUNE 2011 No.465 1 June 2011 PHARMACY ACT, 1974 (ACT NO. 53 OF 1974} LIST OF APPROVED FACILITIES FOR THE PURPOSES OF PERFORMING COMMUNITY SERVICE BY PHARMACISTS IN THE YEAR 2012 The Minister of Health has, in terms of regulation 3 of the Regulations relating to Performance of Pharmaceutical Community Service, listed the following approved facilities for purposes of the profession of pharmacy. PROVINCE REGION/DISTRICT FACILITY EASTERN CAPE Cacadu Andries Vosloo Hospital * Fort England Hospital* Graaf Reneinet CHC* Humansdorp Hospital * Joubertina CHC* Margery Parkes* Marjorie Parish Hospital* Midland Hospital * Orsmond Hospital* Port Alfred Hospital * PZ Meyer* Settlers Hospital * Settlers Day CHC* Temba Hospital• Uitenhage Hospital * Alfred Nzo Khotsong Hospital• Maluti CHC* Mary Theresa Hospital .... ! Mt Ayliff Hospital ** · Sipetu Hospital •• Tabankulu CHC*• Tayler Bequest Hospitai(Maluti) * Tayler Bequest Hospital STAATSKOERANT, 1 JUNIE 2011 No. 34332 97 (Matatiele )"' Chris Hani All Saints Hospital ..... Cala Hospital ** Cofimvaba Hospital ** Cradock Hospital ** Elliot Hospital ... Frontier Hospital * Glen Grey Hospital * Mjanyana Hospital ** NgcoboCHC* Ngonyama CHC* Nomzamo CHC* Sada CHC* Thornhill CHC* Wilhelm Stahl Hospital ..... ZwelakheDalasile CHC* Nelson Mandala Dora Nginza Hospital Elizabeth Donkin Hospital Jose Pearson Santa Hospital Kwazakhele Day Clinic Laetitia Bam CH C Livingstone Hospital Motherwell CHC New Brighton CHC PE Pharmaceutical Depot PE Provincial Hospital Amathole Bedford Hospital Bhisho Hospital Butterworth Hospital Cecilia Makiwane Hospital Cathcart Hospital Dimbaza CHC Duncan Village Day CHC Dutywa CHC Empilweni Gompo CHC Fort Beauford Hospital Fort Grey Hospital Frere Hospital Grey Hospital Middledrift CHC Nontyatyambo CHC Nompomelelo Hospital Ngqamakwe CHC SS Gida Hospita Tafalofefe Hospital Tower Hospital Victoria Hospital Winterberg Hospital Willowvale CHC 98 No. -

Accredited COVID-19 Vaccination Sites Eastern Cape

Accredited COVID-19 Vaccination Sites Eastern Cape Permit Primary Name Address Number 202103960 Fonteine Park Apteek 115 Da Gama Rd, Ferreira Town, Jeffreys Bay Sarah Baartman DM Eastern Cape 202103949 Mqhele Clinic Mpakama, Mqhele Location Elliotdale Amathole DM Eastern Cape 202103754 Masincedane Clinic Lukhanyisweni Location Amathole DM Eastern Cape 202103840 ISUZU STRUANWAY OCCUPATIONAL N Mandela Bay MM CLINIC Eastern Cape 202103753 Glenmore Clinic Glenmore Clinic Glenmore Location Peddie Amathole DM Eastern Cape 202103725 Pricesdale Clinic Mbekweni Village Whittlesea C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103724 Lubisi Clinic Po Southeville A/A Lubisi C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103721 Eureka Clinic 1228 Angelier Street 9744 Joe Gqabi DM Eastern Cape 202103586 Bengu Clinic Bengu Lady Frere (Emalahleni) C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103588 ISUZU PENSIONERS KEMPSTON ROAD N Mandela Bay MM Eastern Cape 202103584 Mhlanga Clinic Mlhaya Cliwe St Augustine Jss C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103658 Westering Medicross 541 Cape Road, Linton Grange, Port Elizabeth N Mandela Bay MM Eastern Cape Updated: 30/06/2021 202103581 Tsengiwe Clinic Next To Tsengiwe J.P.S C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103571 Askeaton Clinic Next To B.B. Mdledle J.S.School Askeaton C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103433 Qitsi Clinic Mdibaniso Aa, Qitsi Cofimvaba C Hani DM Eastern Cape 202103227 Punzana Clinic Tildin Lp School Tildin Location Peddie Amathole DM Eastern Cape 202103186 Nkanga Clinic Nkanga Clinic Nkanga Aa Libode O Tambo DM Eastern Cape 202103214 Lotana Clinic Next To Lotana Clinic Lotana -

Pediatric Palliative Care: Global Perspectives

Pediatric Palliative Care: Global Perspectives Caprice Knapp · Vanessa Madden · Susan Fowler-Kerry Editors Pediatric Palliative Care: Global Perspectives Foreword by Dr. Kathleen M. Foley 123 Editors Dr. Caprice Knapp Dr. Vanessa Madden University of Florida University of Florida Department of Health Outcomes Department of Health Outcomes and Policy and Policy SW 16th Street 1329 SW 16th Street 1329 32610 Gainesville Florida 32610 Gainesville Florida Institute for Child Health Policy Institute for Child Health Policy USA USA [email protected]fl.edu [email protected]fl.edu Dr. Susan Fowler-Kerry University of Saskatchewan College of Nursing College Drive 1121 S7N 0W3 Saskatoon Saskatchewan 306 St Andrew’s College Canada [email protected] ISBN 978-94-007-2569-0 e-ISBN 978-94-007-2570-6 DOI 10.1007/978-94-007-2570-6 Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg London New York Library of Congress Control Number: 2011942747 © Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2012 No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the Publisher, with the exception of any material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com) Foreword Much progress has occurred in the development of pediatric palliative care globally over the last 15 years. Yet, much more needs to be done to address the growing number of children who could benefit from such care. -

Cohsasa News Sept 06

CohsasaThe Newsletter The Council for Health Service Accreditation of Southern Africa TECHNOLOGY UPDATE OCTOBER 2006 New information system is a treasure map COHSASA – in partnership with Xylaco Software – has developed a unique application, which will provide a 360-degree view of strengths, weaknesses and Ten South African urgent improvements needed in health facilities enrolled in COHSASA’s quality hospices accredited improvement and accreditation programmes. Ten hospices in the country, all members of the Hospice Palliative Care Association of Examining 37 areas of operation and measuring both clinical and non- South Africa, have been accredited clinical performance indicators, the new database, migrated from for two years, having met the COHSASA’s multiple legacy databases, will be able to provide professional quality standards clients with quick and easy access to a treasure trove of of COHSASA. information about their hospitals. A total of 47 members of Want to know how your hospital shapes up with regard to the Association entered the infection control? Get your access code, connect on-line and accreditation programme. the COHSASA information system will tell you exactly how Grahamstown Hospice you stand against professional standards, how various was the first to be departments associated with infection control are managing, accredited, followed by what criteria they are meeting and urgent deficiencies that nine others, which have met must be promptly addressed. stringent requirements for Moreover, if you are in the COHSASA Facilitated REWARDING QUALITY: Chairman of COHSASA, the provision of palliative care. Accreditation Programme, you can monitor staff progress and Albert Ramukumba, hands over the accreditation award to the Nursing Services Director of St Francis They were rated on standards pinpoint the bottlenecks and delays. -

COVID-19 Sentinel Hospital Surveillance Weekly Update on Hospitalized Hcws

COVID-19 Sentinel Hospital Surveillance Weekly Update on Hospitalized HCWs Update: Week 36, 2020 Compiled by: Epidemiology and Surveillance Division National Institute for Occupational Health 25 Hospital Street, Constitution Hill, Johannesburg This report summarises data of COVID-19 cases admitted to sentinel hospital surveillance sites in all 1 provinces. The report is based on data collected from 5 March to 5 September 2020 on the DATCOV platform. HIGHLIGHTS As of 5 September 2020, 2 686 (4.2%) of the 64 705 COVID-19 hospital admissions recorded on the DATCOV surveillance database, were health care workers (HCWs), reported from 247 facilities (81 public-sector and 166 private-sector) in all nine provinces of South Africa. Among 801/2686 (29.8%) HCWs with available data on type of work, 391/801 (48.8%) were nurses, 168/801 (21.0%) were categorized as other HCWs, 111/801 (13.9%) porters or administrators, 57/801 (7.1%) allied HCWs, 52/801 (6.5%) doctors, 15/801 (1.9%) paramedics, and 7/801 (0.9%) laboratory scientists. There was an increase of 157 new HCW admissions since week 35. There were 360 (13.4%) and 2326 (86.6%) admissions reported in the public and private sector, respectively. The majority of HCW admissions were reported in Gauteng (834, 31.1%), KwaZulu-Natal (656, 24.4%), Eastern Cape (465, 17.3%) and Western Cape (281, 10.5%). The median age of COVID-19 HCW admissions was 49 years, there were 482 (17.9%) admissions in HCWs aged 60 years and older. A total of 1912 (71.2%) were female. -

District Hospital Performance Assessment Report E

District Hospital Performance Assessment Eastern Cape 2008-2010 [Part 1: Cacadu (DC10), Amatole (DC12) and Chris Hani (DC13) Districts] Sizulu Moyo, Thokozani Mbatha, Catherine Ogunmefun, Peter Bock, Rene English District Hospital Performance Assessment Eastern Cape 2008-2010 [Part 1: Cacadu (DC10), Amatole (DC12) and Chris Hani (DC13) Districts] Sizulu Moyo, Thokozani Mbatha, Catherine Ogunmefun, Peter Bock, Rene English Published by Health Systems Trust 34 Essex Terrace Tel: +27 (0)31 266 9090 Westville Fax: +27 (0)31 266 9199 3630 Email: [email protected] South Africa http://www.hst.org.za Published: November 2011 Suggested citation: Moyo S, Mbatha T, Ogunmefun C, Bock P, English R. District Hospital Performance Assessment: Eastern Cape Province 2008-1010 Part 1. Health Systems Trust; Durban, 2012 The information contained in this publication may be freely distributed and reproduced, as long as the source is acknowledged, and it is used for non-commercial purposes. Acknowledgements We would like to thank the National Department of Health for providing the data for the report. We are also grateful to Candy Day for assistance with the data. We thank Dr Peter Barron for input and guidance in writing the final report. District Hospital Performance Assessment: Eastern Cape Province 2008-2010 [Part 1] i Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 1 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................ -

2016 Province District List of Facilities Number of Posts 1. Eastern

Available funded posts for Pharmacist Community Service -2016 Number Province District List of facilities of posts 1. Eastern Cape Amathole Adelaide Hospital (1) Komga Hospital (1) Stutterheim Hospital (1) Bedford Hospital (1) Madwaleni Hospital (1) Tafalofefe Hospital (1) Butterworth Hospital (1) Nompumelelo Hospital (1) Tower TB Hospital (1) Carthcart Hospital (1) Nqamakhwe CHC (1) Victoria Hospital (1) 14 Fort Beaufort Hospital (1) SS Gida Hospital (1) Alfred Nzo Maluti CHC (1) Mount Ayliff Hospital (1) Taylor Bequest Hospital (1) 03 Buffalo City Bhisho (1) Empilweni Gompo Day Grey Hospital (1) Dimbaza CHC (1) Hospital (1) Nkqubela TB Hospital (1) Duncan Village Day Fort Grey (1) 07 Hospital (1) Cacadu Andries Vosloo (1) Midlands Hospital (1) Settlers CHC (1) Fort England Hospital (1) Port Alfred Hospital (1) Temba TB Hospital (1) Humansdorp Hospital (1) PZ Meyer TB Hospital (1) Wilhelm Stahl Hospital (1) 12 Margery Parkes (1) Settlers Hospital (1) Willowmore Hospital (1) Chris Hani All Saints Hospital (1) Dordrecht Hospital (1) Indwe Hospital (1) Cala Hospital (1) Elliot Hospital (1) Komani Hospital (1) Cofimvaba Hospital (1) Frontier Hospital (1) Maclear Hospital (1) 12 Cradock Hospital (1) Clen Grey Hospital (1) Moltena Hospital (1) Joe Gqabi Aliwal North Hospital (1) Empilisweni Hospital (1) Tayler Bequest Hospital (1) Burgersdorp Hospital (1) Lady Grey Hospital (1) Umlamli Hospital (1) 07 Cloete Jourbet Hospital (1) Nelson Mandela PE Pharmaceutical Depot (1) Kwa Zwakhele CHC (1) Orsmond TB Hospital (1) Metro Empilweni Hospital -

Public-Private Partnerships' Contribution to Quality Healthcare- A

PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS’ CONTRIBUTION TO QUALITY HEALTHCARE: A CASE STUDY FOR SOUTH AFRICA AFTER 1994 by MONGI JAMES JOKOZELA submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree Magister Commercii in Economics in the Faculty of Economic and Financial Sciences at the University of Johannesburg Supervisor: Professor Ronald Mears May 2012 Johannesburg ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to a number of people for the success of this study. I would like to acknowledge the support, guidance and encouragement of my Supervisor, Professor Ronald Mears of the Department of Economics and Econometrics at the University of Johannesburg. I thank you for your thoughtful advice and direction in my studies. My sincere thanks and love to my wife, Lindiwe Jokozela for believing in me and always supporting me in my studies. To my kids who missed the love and attention of their father during my studies. A special thanks to my parents for bringing me up to be the person I am today and the community of Hillside village in whose environment I grew up. Lastly, I thank my work and student colleagues, friends and family for their encouragement and support throughout my studies. Opinions expressed and conclusions derived, are those of the author and not necessarily to be attributed to the University of Johannesburg. ii DECLARATION I, declare that Public-Private Partnerships’ contribution to quality healthcare: a case study of South Africa after 1994 is my own work, that all the sources used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references, and that the research was not previously submitted by me for a degree at another University. -

Health Professions Act (56/1974): List of Approved Facilities for the Purposes of Performing Community Service by Physiotherapists in the Year 2016 39070

STAATSKOERANT, 6 AUGUSTUS 2015 No. 39070 31 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH NO. 684 06 AUGUST 2015 684 Health Professions Act (56/1974): List Of Approved Facilities For The Purposes Of Performing Community Service By Physiotherapists In The Year 2016 39070 HEALTH PROFESSIONS ACT, 1974 (ACT NO. 56 OF 1974) LIST OF APPROVED FACILITIES FOR THE PURPOSES OF PERFORMING COMMUNITY SERVICE BY PHYSIOTHERAPISTS IN THE YEAR 2016 The Minister of Health has, in terms of regulation 5.1 of the Regulations relating to Performance of Community Service by Persons Registering in terms of the Health Professions Act, 1974 (Act No. 56 of 1974), listed the following approved facilities for purposes of the profession of physiotherapy PROVINCE REGION /DISTRICT FACILITY EASTERN Amatole Mbhashe Sub -District CAPE o Idut a CHH * Madwaleni Hospital * e Tafalofefe Hospital Mnquma Sub -District Butterworth Hospital e Ngqamakhwe CHH Nkonkobe Sub -District e Adelaide FPAH * Bedford CHH Fort Beaufort CHH * Tower Psychiatric Hospital Victoria Hospital * This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za 32 No. 39070 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 6 AUGUST 2015 Alfred Nzo Green Ville CHH Madzikane ka Zulu Hospital Mt AyI iff CHH * St Patricks Hospital * Taylor Bequest Hospital (Matatiele) * Buffalo City Metro Bisho Hospital * Cathcart CHH * ® Cecilia Makiwane Hospital ® Empilweni Gompo CHC Frere Hospital Fort Grey TB Hospital Grey Hospital Komgha FPAH Nompumelelo Hospital S.S.Gida CHH * Stuttherheim CHH * Cacadu Camdeboo Sub -District Andries Vosloo Hospital ® Abardeen FPAH Midlands Hospital * Sawas FPAH Kouga Sub -District BJ Forster FPAH Humansdorp Hospital * e Joubertina CHC * Makana Sub -District s Fort England Psychaitric Hospital * e Majorie Parish TB Hospital * o Port Alfred Hospital * This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za STAATSKOERANT, 6 AUGUSTUS 2015 No. -

Sentinel Hospital Surveillance Week 34

COVID-19 SENTINEL HOSPITAL SURVEILLANCE UPDATE SOUTH AFRICA WEEK 34 2020 OVERVIEW This report summarises data of COVID-19 cases admitted to sentinel hospital surveillance sites in all provinces. The report is based on data collected from 5 March to 22 August 2020. HIGHLIGHTS discharged), the case fatality ratio (CFR) ∙ As of 22 August, 58 594 COVID-19 admissions was 19%. On multivariable analysis, factors were reported from 414 facilities (173 public- associated with in-hospital mortality were sector and 241 private-sector) in all nine older age groups; male sex; Black African, provinces of South Africa. There was an Coloured and Indian race; admission in increase of 9 466 admissions reported since the public sector; and having comorbid the last report, and 34 additional hospitals (29 hypertension, diabetes, chronic cardiac public-sector and 5 private-sector) reporting disease, chronic renal disease, malignancy, COVID-19 admissions. There were 19 247 HIV, current tuberculosis alone or both (33%) and 39 347 (67%) admissions reported current and past tuberculosis, and obesity. in public and private sector respectively. Compared to the Western Cape province, The majority of COVID-19 admissions were individuals hospitalised in Eastern Cape, reported from four provinces, 16 983 (29%) Free State, Gauteng, Limpopo and North in Western Cape, 16 090 (28%) in Gauteng, West provinces were more likely to die in- 9 347 (16%) in KwaZulu-Natal and 6 937 hospital. (12%) in Eastern Cape. Admissions in the Western Cape, Eastern Cape and Gauteng have decreased and there are indications of slowing of the rate of increase in admissions in the other provinces over the past three weeks. -

Eastern Cape Department of Health Applications

ANNEXURE R PROVINCIAL ADMINISTRATION: EASTERN CAPE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH APPLICATIONS : Applications directed to the addresses as indicated below or Hand Delivery as indicated below: Cecilla Makiwane Hospital - Post to: Cecilia Makiwane Hospital: Private Bag X 001, Mdantsane, 5225 Or Hand Deliver to Human Resource Office, Cecelia Makiwane Hospital, and Billie Road, Mdantsane: Enquiries: Ms N. Matshaya Tel No: (043) 708 2121. Nkqubela Hospital - Post to: HR Office, Nkqubela Hospital, PO Box x9047 Cambridge East London 5206 or hand deliver to: HR Office, Nkqubela Hospital, Billie Road, Mdantsane Township. Enquires: Ms Langeni Tel No: (043) 761 2131 Buffalo City Metro District Office - Post to: HR Office, Buffalo City Metro District Office, Private Bag X9015, East London, 5200 or hand Deliver to: HR Office, Buffalo City Metro District Office, 18 Sheffield Road Woodbrook West Bank East London 5200. Enquires: Ms H Hlulani Tel. No: (043) 7433 006/057 Bhisho Hospital: - Post to: HR Office, Bhisho Hospital, Bhisho 5605 or hand delivery: Human Resource Office, Bhisho Hospital Komga Road. Enquiries: Mrs T. Awlyn – Qegu Tel No: (040) 635 2950/5. Uitenhage Provincial Hospital - Post to: HR Office, Private Bag X36, Uitenhage, 6230 or hand deliver to: HR Office, Uitenhage Provincial Hospital, 36 Channer Street, Levyvale, Uitenhage 6229. Enquiries: Mr P Oosthuizen Tel No: (041) 995 1129. Madzikane Ka Zulu Hospital - Post to: HR Office Madzikane ka Zulu Hospital Private Bag x9003 Mt Frere 5900 Enquiries Mr Sigola Tel No: 039 255 8200/11/12. Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital - Post to: Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital, Private Bag x5014 Mthatha 5099. Hand Deliver to: Human Resource Office, Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital, Nelson Mandela Drive, Mthatha 5099.