Business Accountability for Human Rights Violations in the Assam Tea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lot 1 Collection of Decorative Glassware Including Uranium Glass (1 Tray) Estimate: 0 - 0 Fees: 21% Inc VAT

Byrne's Auctioneers - General & Collectors Auction - Starts 04 Sep 2019 Lot 1 Collection of decorative glassware including uranium glass (1 tray) Estimate: 0 - 0 Fees: 21% inc VAT Lot 2 Masonic regalia, leather bag, glassware, ceramics etc (1 tray) Estimate: 0 - 0 Fees: 21% inc VAT Lot 3 Gilt framed Baxter print; also further gilt framed prints and framed telegram (6) Estimate: 0 - 0 Fees: 21% inc VAT Lot 4 Mason's Ironstone Mandalay pattern jug and pedestal bowl; also pair of silver plated candlesticks, silver plated figures, further ceramics (1 tray) Estimate: 0 - 0 Fees: 21% inc VAT Lot 5 Vintage treen including butter pats; also pewter tankards etc (1 tray) Estimate: 0 - 0 Fees: 21% inc VAT Lot 6 Andrew Hutchinson, framed limited edition print; also an unframed print (2) Estimate: 0 - 0 Fees: 21% inc VAT Lot 7 Victorian Staffordshire spaniel; also Belleek porcelain tea wares, blue and white printware, other decorative ceramics and glass (3 trays) Estimate: 0 - 0 Fees: 21% inc VAT Lot 8 Chinese blue and white Prunus pattern ginger jar with printed Kangxi mark, 19th Century Spode china, saucers, further decorative china including jugs (2 trays) Estimate: 0 - 0 Fees: 21% inc VAT Lot 8a Watercolour landscape painting, further framed landscape prints and a framed Michael Bell pastel (5) Estimate: 0 - 0 Fees: 21% inc VAT Lot 9 Victorian Staffordshire spaniel, further decorative china including Pendelfin figures, Crested ware battleship, majolica dishes Estimate: 0 - 0 Fees: 21% inc VAT Lot 10 W Watson & Sons Ltd London, 1917 binoculars with -

Participant List

PARTICIPANT LIST Please find below a list of current participants in the Quarterly Salary Review. For a complete list by super sector, sector and segment refer to Mercer WIN®. 3M Australia API 7-Eleven Stores API Management A Menarini Australia APL Co. (Aus) - BR A.P.Moller-Maersk AS (AU) Apotex Abbott Australasia APT Management Services (APA Group) AbbVie Aquila Resources Actelion Pharmaceuticals Australia Arrium Mining & Materials Adama Australia Arrow Electronics Australia Adelaide Brighton Asahi Beverages Australia Adelaide Football Club Asaleo Care Australia adidas Australia Ascendas Hospitality Australia Fund Management Adventist Healthcare Aspen Australia AECOM Astrazeneca Afton Chemical Asia Pacific LLC AT & T Global Network Services Australia Aggreko Australia ATCO Australia AIA Australia Atlas Iron Aimia Proprietary Loyalty Australia Ausenco Air New Zealand – Australia AusGroup Akzo Nobel Australia Australia Post Alcatel-Lucent Australia Australian Catholic University Alcon (Novartis) Laboratories Australia Australian Computer Society Alexion Australasia Australian Fashion Labels Allergan Australian Red Cross Blood Service Alphapharm Avaloq Australia Alstom Transport Australia Aveo Group Amadeus IT Pacific Aviall Australia American Express Global Business Travel Australia AVJennings Holdings Amgen Australia Avon Products AMT Group BaptistCare NSW & ACT Amway of Australia Barminco Apex Tool Group BASF Australia © March 2017 Mercer Consulting (Australia) Pty Ltd Quarterly Salary Review 4.1 PARTICIPANT LIST Beam Global Australia -

CONTACT US Call Your Local Depot, Or Register Online with Our Easy to Use Website That Works Perfectly on Whatever Device You Use

CONTACT US Call your local depot, or register online with our easy to use website that works perfectly on whatever device you use. Basingstoke 0370 3663 800 Nottingham 0370 3663 420 Battersea 0370 3663 500 Oban 0163 1569 100 Bicester 0370 3663 285 Paddock Wood 0370 3663 670 Birmingham 0370 3663 460 Salisbury 0370 3663 650 Chepstow 0370 3663 295 Slough 0370 3663 250 Edinburgh 0370 3663 480 Stowmarket 0370 3663 360 Gateshead 0370 3663 450 Swansea 0370 3663 230 Harlow 0370 3663 520 Wakefield 0370 3663 400 Lee Mill 0370 3663 600 Worthing 0370 3663 580 Manchester 0370 3663 400 Bidvest Foodservice 814 Leigh Road Slough SL1 4BD Tel: +44 (0)370 3663 100 http://www.bidvest.co.uk www.bidvest.co.uk Bidvest Foodservice is a trading name of BFS Group Limited (registered number 239718) whose registered office is at 814 Leigh Road, Slough SL1 4BD. The little book of TEA 3 Contents It’s Tea Time! With a profit margin of around 90%*, tea is big business. We have created this guide to tea so help you make the most of this exciting opportunity. Tea Varieties .............................. 4 Tea Formats ............................... 6 With new blends and infusions such as Chai and Which Tea Is Right For You? .... 8 Matcha as well as traditional classics such as Earl Profit Opportunity ....................10 Grey and English Breakfast, we have something for Maximise Your Tea Sales .......12 all, helping to ensure your customers’ tea experience The Perfect Serve ....................15 The Perfect Display .................16 will be a talking point! The Perfect Pairing ..................18 Tea & Biscuit Pairing ...............20 Tea Geekery ............................21 Recipes .....................................22 Tea Listing ................................28 4 People’s passion for tea All about tea has been re-ignited. -

Empire of Tea

Empire of Tea Empire of Tea The Asian Leaf that Conquered the Wor ld Markman Ellis, Richard Coulton, Matthew Mauger reaktion books For Ceri, Bey, Chelle Published by Reaktion Books Ltd 33 Great Sutton Street London ec1v 0dx, uk www.reaktionbooks.co.uk First published 2015 Copyright © Markman Ellis, Richard Coulton, Matthew Mauger 2015 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers Printed and bound in China by 1010 Printing International Ltd A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library isbn 978 1 78023 440 3 Contents Introduction 7 one: Early European Encounters with Tea 14 two: Establishing the Taste for Tea in Britain 31 three: The Tea Trade with China 53 four: The Elevation of Tea 73 five: The Natural Philosophy of Tea 93 six: The Market for Tea in Britain 115 seven: The British Way of Tea 139 eight: Smuggling and Taxation 161 nine: The Democratization of Tea Drinking 179 ten: Tea in the Politics of Empire 202 eleven: The National Drink of Victorian Britain 221 twelve: Twentieth-century Tea 247 Epilogue: Global Tea 267 References 277 Bibliography 307 Acknowledgements 315 Photo Acknowledgements 317 Index 319 ‘A Sort of Tea from China’, c. 1700, a material survival of Britain’s encounter with tea in the late seventeenth century. e specimen was acquired by James Cuninghame, a physician and ship’s surgeon who visited Amoy (Xiamen) in 1698–9 and Chusan (Zhoushan) in 1700–1703. -

Litchat 2009 10 5-7 Inspirational Lit.Xlsx

LitChat October 5 ‐ 7, 2009 Topic of the Week: CONTEMPORARY INSPIRATIONAL LITERATURE Open chat MONDAY, October 5, 2009 LitChat Welcome to a new week and a new topic in #litchat. We're discussing CONTEMPORARY INSPIRATIONAL LITERATURE all week. LitChat begins now. ‐12:58 PM Oct 5th, 2009 LexxClarke @rebeccawoodhead evening Randomer ;o) #litchat ‐12:59 PM Oct 5th, 2009 GLeeHancock @rebeccawoodhead @writeranonymous Welcome! What time is it on your side of the pond? I'm in CA, so it's just 1 P.M. or pippa emma #litchat ‐12:59 PM Oct 5th, 2009 LexxClarke @llunalila ello :O) #litchat ‐12:59 PM Oct 5th, 2009 LexxClarke @writeranonymous welcome to #litchat ‐1:00 PM Oct 5th, 2009 rebeccawoodhead @thenewauthor ‐ are you on #litchat ? Inspirational literature tonight ‐ bet you've got lots of good stuff to say ‐1:00 PM Oct 5th, 2009 writeranonymous @GLeeHancock Just gone 9pm =] #litchat ‐1:01 PM Oct 5th, 2009 rebeccawoodhead @LexxClarke randomer..randomer.. lol...lol... good times.times. #litchat ‐1:01 PM Oct 5th,5th, 2009 writeranonymous @LexxClarke Many thanks! I feel so intimidated by this already! #litchat ‐1:01 PM Oct 5th, 2009 LitChat I see some new names this week. Welcome everyone. I hope @ampersandagency doesn't get barraged with pitches. #litchat ‐1:01 PM Oct 5th, 2009 rebeccawoodhead @GLeeHancock it's 9pm here. Am hoping @thejohnkeenan from The Guardian will be here tonight. He keeps missing it #litchat ‐1:01 PM Oct 5th, 2009 BenRubinstein @rebeccawoodhead Hello! See, I said I'd be here, and here I am :) Although I have no business being here withih thishi topiic :‐p #li#litchat h ‐1011:01 PM OOct 5h5th, 2009 LexxClarke @rebeccawoodhead hehe #litchat ‐1:02 PM Oct 5th, 2009 ficwriter Rt @LitChat Welcome to a new week and new topic in #litchat. -

The Annual Report on the Most Valuable British Brands April 2017

United Kingdom 150 2017 The annual report on the most valuable British brands April 2017 Foreword. Contents steady downward spiral of poor communication, Foreword 2 wasted resources and a negative impact on the bottom line. Definitions 4 Methodology 6 Brand Finance bridges the gap between the marketing and financial worlds. Our teams have Excecutive Summary 8 experience across a wide range of disciplines from market research and visual identity to tax and Full Tables (GPBm & USDm) 14 accounting. We understand the importance of design, advertising and marketing, but we also Understand Your Brand’s Value 20 believe that the ultimate and overriding purpose of How We Can Help 22 brands is to make money. That is why we connect brands to the bottom line. Contact Details 23 By valuing brands, we provide a mutually intelligible language for marketers and finance teams. David Haigh, CEO, Brand Finance Marketers then have the ability to communicate the significance of what they do and boards can use What is the purpose of a strong brand; to attract the information to chart a course that maximises customers, to build loyalty, to motivate staff? All profits. true, but for a commercial brand at least, the first Without knowing the precise, financial value of an answer must always be ‘to make money’. asset, how can you know if you are maximising your returns? If you are intending to license a brand, how Huge investments are made in the design, launch can you know you are getting a fair price? If you are and ongoing promotion of brands. -

Members' Directory

ROYAL WARRANT HOLDERS ASSOCIATION MEMBERS’ DIRECTORY 2019–2020 SECRETARY’S FOREWORD 3 WELCOME Dear Reader, The Royal Warrant Holders Association represents one of the most diverse groups of companies in the world in terms of size and sector, from traditional craftspeople to global multinationals operating at the cutting edge of technology. The Members’ Directory lists companies by broad categories that further underline the range of skills, products and services that exist within the membership. Also included is a section dedicated to our principal charitable arm, the Queen Elizabeth Scholarship Trust (QEST), of which HRH The Prince of Wales is Patron. The section profiles the most recent alumni of scholars and apprentices to have benefited from funding, who have each developed their skills and promoted excellence in British craftsmanship. As ever, Royal Warrant holders and QEST are united in our dedication to service, quality and excellence as symbolised by the Royal Warrant of Appointment. We hope you find this printed directory of use when thinking of manufacturers and suppliers of products and services. An online version – which is regularly updated with company information and has enhanced search facilities – can be viewed on our website, www.royalwarrant.org “UNITED IN OUR DEDICATION TO Richard Peck SERVICE, QUALITY CEO & Secretary AND EXCELLENCE” The Royal Warrant Holders Association CONTENTS Directory of members Agriculture & Animal Welfare ...............................................................................................5 -

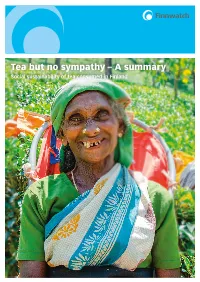

Tea but No Sympathy – a Summary

Tea but no sympathy – A summary Social sustainability of tea consumed in Finland Supported by crowdfunding organised on the People´s Cultural Foundation’s Kulttuurilahja -plat- form and by the Finnwatch Decent Work Research Programme. The Programme is supported by: An abbreviated and translated version of the original Finnish report. In the event of interpretation disputes the Finnish text applies. The original is available at www.fi nnwatch.org. Finnwatch is a non-profi t organisation that investigates the global impacts of Finnish business en- terprises. Finnwatch is supported by 11 development, environmental and consumer organisations and trade unions: The International Solidarity Foundation ISF, Finnish Development NGOs – Fingo, The Finnish Evangelical Lutheran Mission Felm, Pro Ethical Trade Finland, The Trade Union Solidarity Centre of Finland SASK, Attac, Finn Church Aid, The Dalit Solidarity Network in Finland, Friends of the Earth Finland, KIOS Foundation and The Consumers’ Union of Finland. Layout: Petri Clusius/Amfi bi ky Publication date: October 2019 Cover photo: A worker on a tea plantation in the Nuwara Eliya district in Sri Lanka. The person in the photo is not connected to Finnwatch’s investigation. Finnwatch will not publish pictures of the individuals who were intervie- wed for this report due to consideration for their safety. Contents 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. 4 2. INDIA: THE NILGIRIS ..................................................................................................................... -

The Full Agenda

TUESDAY MAY 25TH 2021 This could be titled “How To Be Human When Doing Business” and has been two decades in the making. Enjoy learning our Super Seven and getting plenty time to practise them too, with a few hundred others. 9.00am to 9.30am: ARRIVE EARLY, REGISTER, TWEAK YOUR TECH, GIVE THE CAT A BONE Half an hour to settle you down, get you chatting, look for the fire exits (patio doors?) and quiz the techies. (three warm mini cinnamon swirls, flat white with an extra shot) 9.30am to 9.35am: WELCOME Managing Director Sharon McLellan: hot buttery croissant, blackcurrant jam, large mug of strong coffee. YOUR CONFERENCE SPEAKERS: Nicky Denegri: American pancakes, maple syrup, blueberries, double expresso Michael Fleming: Scots’ porridge oats, banana, honey, latte. Russell Wardrop: warm almond croissant, toasted shards on top, cortado. 9.35am to 10.45am: Session One (a pyramid of pain au raisins, crunchy on the outside, minty tea.) 1) SELF-AWARENESS IS YOUR TOUCHSTONE: Key traits, from the Cocktail Bar to the Boardroom, that the best rainmakers have (whisper it: they learned them.). 2) ACCENTUATE THE POSITIVE: Four brilliant ways to be optimistic, starting today at noon. Nobody likes a miserable bar-steward. 3) BE A CHAMELEON: Flex your style and adapt seamlessly to your environment; versatility is a high-level skill, you need to be on it. 10.45 to 11am: Break for fifteen (Mr. Kipling Cherry Bakewells, milky Yorkshire tea.) 11.00am to 12.15pm: Session Two (Home-made, gooey, double choc-chip cookies, Masala Chai) 4) BE APPROPRIATELY MEMORABLE: If you are not visible you are invisible; four ways to be remembered after you’ve gone home (I know you may be mostly home, but still). -

Corporate Responsibility for Human Rights in Assam Tea Plantations: a Business and Human Rights Approach

sustainability Article Corporate Responsibility for Human Rights in Assam Tea Plantations: A Business and Human Rights Approach Madhura Rao 1 and Nadia Bernaz 2,* 1 Food Claims Centre Venlo, Maastricht University, 5911 BV Venlo, The Netherlands; [email protected] 2 Law Group, Wageningen University, 6708 PB Wageningen, The Netherlands * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 16 July 2020; Accepted: 7 September 2020; Published: 9 September 2020 Abstract: This paper explores how UK-based companies deal with their responsibility to respect the human rights of Assam (India) tea plantation workers. Through qualitative content analysis of publicly available corporate reports and other documents, it investigates how companies approach and communicate their potential human rights impacts. It highlights the gap between well-documented human rights issues on the ground and corporate reports on these issues. It aims to answer the following research question: in a context where the existence of human rights violations at the end of the supply chain is well-documented, how do companies reconcile their possible connection with those violations and the corporate responsibility to respect human rights under the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights? This paper reveals the weakness of the current corporate social responsibility (CSR) approach from the perspective of rights-holders. It supports a business and human rights approach, one that places the protection of human rights at its core. Keywords: tea plantations; Assam; business and human rights; corporate social responsibility; UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights; UK Modern Slavery Act 1. Introduction This paper explores how UK-based tea companies deal with their responsibility to respect the human rights of Assam tea plantation workers. -

LUNCH V3 SUMMER Reopening 2021

Please order at the counter (don't forget your table number) Any allergies in your party? Please notify us when placing your order. SUMMER LUNCH Lunch orders taken from 12.00pm to 3.00pm LARGER BITES spicy meat balls 7.49 with sourdough bread & mixed leaves homemade sausage roll 8.99 seasoned with apricot and fennel seeds, mixed vegan pasty 5.99 leaves & potato salad chickpea, onion & cauliflower & mixed leaves (Ve) quiche - lorraine 8.99 welsh rarebit 5.99 cheese and bacon, mixed leaves & potato salad toasted sourdough, mature cheddar, mustard, mayonnaise & watercress leaves (V) quiche - roasted vegetable & cheese 8.99 mixed leaves & potato salad (V) roasted vegetable pasta bake 7.49 tomato sauce & vegan cheese, mixed leaves (Ve) LIGHTER BITES / SALADS SANDWICH / JACKET POTATO with mixed leaves soup - tomato & basil or leek & potato 5.49 served with bread rolls (Ve) tuna & sweetcorn mayo 6.49/7.49 citrus cured salmon salad 8.99 cheddar cheese & coleslaw (V) 5.49/6.49 artichoke & orange segments, rocket & watercress leaves coronation chicken 6.49/7.49 roasted vegetable salad 7.99 cheese & crispy bacon 5.99/6.99 with new potatoes, mixed leaves (Ve) breakfast sandwich 5.99 chicken & avocado salad 8.99 bacon, sausage, or vegetarian sausage (V), white or new potatoes, mixed leaves topped with crispy bacon multigrain bloomer toasted tea bread 3.99 with butter & jam (V) KIDS* waffles with maple syrup & bacon 4.49 creamy tomato pasta (v) 3.99 with berry compote (V) 3.99 with nutella & banana (V) 3.99 bacon or sausage sandwich 2.99 baked beans on toast (V) 2.99 EXTRAS 1/2 jacket potato with cheese (V) 3.99 potato salad (V) 2.49 sandwich - cheese 3.99 mixed salad (Ve) 2.49 white or multigrain bloomer (V) coleslaw (V) 1.99 kids waffles 3.49 bread rolls (v) 1.49 with nutella (V) Please don't forget our usual range of exquisite patisserie, cakes, scones and treats. -

Cuisine ⁞ Culture ⁞ Connoisseur ⁞ Connections

CUISINE ⁞ CULTURE ⁞ CONNOISSEUR ⁞ CONNECTIONS TheTeaHouseTimes.com | January/February 2018 ADVERTISING Connecting Businesses & Consumers Since 2003 TEA www.BigelowTea.com MISCELLANEOUS Family Tea Blenders Since 1945 www.KyuemonFilter.com/index_en.html The Pinnacle of Pour-Over Evolution! www.CaliforniaTeaHouse.com Gourmet Loose Leaf Tea www.TeaFoodHistory.com Tea & Food Programs and Workshops www.DoehiTea.com Delivering the finest teas from around the world. www.TeaRoomChocolates.com An International Journey of Culture & Taste www.FergiesFCC.com Image: Madlen/Shutterstock.com Fergie’s Flying Culinary Circus TEA READING ASSOCIATIONS www.GoldenTLeaf.com www.Tea.ca www.EarleneGrey.com Award Winning Tea Estate and Company Tea Association of Canada Tea Poetry and presentations. Unexpected fun! www.GreenhalghTea.com www.TeaUSA.org www.JamesNorwoodPratt.com Select single estate tea & blends, accessories. Tea Association of the USA James Norwood Pratt - tea expertise and books. www.SerendipiTea.com www.TheLeaseCoach.com Highest quality loose leaf teas & tisanes CONNECTIONS Help for Signing a Commercial Lease/Renewal. www.TeaBureau.com www.SolleInfusions.com Tea Business Directory, News, Speakers Bureau SHOWS/EVENTS Healthy, tasty fruit, tea & herbal infusions. www.TeaSpeakersBureau.com www.CoffeeFest.com www.SVTea.com Trade show: find coffee, tea, and education Find Speakers and Tea Specialists or Get Listed Quality Teas and Tisanes Since 1929 www.TheTeaHouseTimes.com www.CoffeeAndTeaFestival.com www.Tea-For-All.com Publication - News - Education Open to the public! Shop, taste, learn. Explore Tea-For-All™ & discover your “TEA” www.WorldTeaExpo.com www.TeaNTeas.com EDUCATION Trade show: tea, accessories, and education Teas-Tisanes-Herbs-Spices-direct from source www.CharlestonSchoolofProtocol.com Seminars, consulting services, etiquette, protocol Find a calendar of events and programs via www.TheCozyTeaCart.com TheTeaHouseTimes.com website Quality teas, accoutrements, specialty gifts www.CulinaryTeaCourse.com Tea Education with a Culinary Focus.