Also by Leo F. Goodstadt China's Search for Plenty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Record of Proceedings

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 3 November 2010 1399 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 3 November 2010 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. 1400 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 3 November 2010 THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TIMOTHY FOK TSUN-TING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. -

The RTHK Coverage of the 2004 Legislative Council Election Compared with the Commercial Broadcaster

Mainstream or Alternative? The RTHK Coverage of the 2004 Legislative Council Election Compared with the Commercial Broadcaster so Ming Hang A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Government and Public Administration © The Chinese University of Hong Kong June 2005 The Chinese University of Hong Kong holds the copyright of this thesis. Any person(s) intending to use a part or whole of the materials in the thesis in a proposed publication must seek copyright release from the Dean of the Graduate School. 卜二,A館書圆^^ m 18 1 KK j|| Abstract Theoretically, public broadcaster and commercial broadcaster are set up and run by two different mechanisms. Commercial broadcaster, as a proprietary organization, is believed to emphasize on maximizing the profit while the public broadcaster, without commercial considerations, is usually expected to achieve some objectives or goals instead of making profits. Therefore, the contribution by public broadcaster to the society is usually expected to be different from those by commercial broadcaster. However, the public broadcasters are in crisis around the world because of their unclear role in actual practice. Many politicians claim that they cannot find any difference between the public broadcasters and the commercial broadcasters and thus they asserted to cut the budget of public broadcasters or even privatize all public broadcasters. Having this unstable situation of the public broadcasting, the role or performance of the public broadcasters in actual practice has drawn much attention from both policy-makers and scholars. Empirical studies are divergent on whether there is difference between public and commercial broadcaster in actual practice. -

RTHK UNDER SIEGE Hong Kong Government Takes on the Public Broadcaster

RTHK UNDER SIEGE Hong Kong Government Takes on the Public Broadcaster 2006 ANNUAL REPORT REPORT OF THE HONG KONG JOURNALISTS ASSOCIATION JULY 2006 Hong Kong Government Takes on the Public Broadcaster: 2006 Annual Report 1 Contents Introduction and recommendations ................................................................................................................2 Section 1 GOVERNMENT TARGETS PUBLIC BROADCASTING ............................5 A chequered history................................................................................6 Beijing thwarts formal independence ....................................................6 Pro-Beijing voices of disapproval ...........................................................7 At last, the review goes forward .............................................................8 So far so good, but where are the critics?...............................................8 RTHK faces pressure on other fronts ....................................................10 Public access becomes an issue.............................................................11 Section 2 PROJECTING A FUTURE FOR RTHK ....................................................12 RTHK’s role...........................................................................................12 RTHK and public...................................................................................12 Programme producer............................................................................12 Public connector...................................................................................13 -

Basic Law and Hong Kong's Bilateral Relations

External Relations of Hong Kong: The Most Neglected Subject in International Relations? Colonial Law: Promulgated by the UK Basic Law: As Authorized by the NPC of PRC › No Nullifying Power › Full Sovereignty from PRC The Central People's Government shall be responsible for the foreign affairs relating to the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China shall establish an office in Hong Kong to deal with foreign affairs. The Central People's Government authorizes the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region to conduct relevant external affairs on its own in accordance with this Law. Representatives of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region may, as members of delegations of the Government of the People's Republic of China, participate in negotiations at the diplomatic level directly affecting the Region conducted by the Central People's Government. The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region may on its own, using the name ""Hong Kong, China "", maintain and develop relations and conclude and implement agreements with foreign states and regions and relevant international organizations in the appropriate fields, including the economic, trade, financial and monetary, shipping, communications, tourism, cultural and sports fields. WTO: “Tariff” APEC: “Economy” FIFA: “Domestic League” The application to the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of international agreements to which the People's Republic of China is or becomes a party shall be decided by the Central People's Government, in accordance with the circumstances and needs of the Region, and after seeking the views of the government of the Region. -

Hansard of the Former Legislative Council Then, I Note the Request Made by Many Honourable Members That Direct Elections Be Held for ADC Members

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 25 May 2011 10789 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 25 May 2011 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. 10790 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 25 May 2011 THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TIMOTHY FOK TSUN-TING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE AUDREY EU YUET-MEE, S.C., J.P. -

Negotiating Positive Non-Interventionism: Regulating Hong Kong’S Finance Companies, 1976-86.China Quarterly, 230, Pp

Schenk, C. R. (2017) Negotiating positive non-interventionism: regulating Hong Kong’s finance companies, 1976-86.China Quarterly, 230, pp. 348- 370. (doi:10.1017/S0305741017000637) This is the author’s final accepted version. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/120818/ Deposited on: 08 July 2016 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk33640 Negotiating Positive Non-Interventionism: Regulating Hong Kong’s Finance Companies 1976-861 Catherine R. Schenk Accepted for publication in China Quarterly (2017) The principle of Positive Non-Interventionism coined by Hong Kong’s Financial Secretary Sir Philip Haddon-Cave in the 1970s has come to dominate perceptions of Hong Kong’s successful post-war economic development. The deliberate effort by the state not to intervene in the allocation of productive resources, but instead to rely on market forces drew plaudits from free-market enthusiasts such as Milton Friedman in the 1980s and was a marked contrast to the ‘governed market’ that prevailed in other East Asian newly industrialising economies such as South Korea and Taiwan.2 The death of positive non- interventionism has been announced several times: as early as 1992 by Financial Secretary Hamish Macleod, then by Chief Executive Donald Tsang in September 2006 and again in August 2015 by his successor Leung Chun-ying. 3 The slogan has persisted despite a turn to ‘big market-small government’ in the mid-2000s. -

Minutes Have Been Seen by the Administration)

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(1)2299/04-05 (These minutes have been seen by the Administration) Ref : CB1/PL/ITB/1 Panel on Information Technology and Broadcasting Minutes of special meeting held on Thursday, 21 July 2005, at 4:30 pm in the Chamber of the Legislative Council Building Members present : Hon SIN Chung-kai, JP (Chairman) Hon Albert Jinghan CHENG (Deputy Chairman) Dr Hon LUI Ming-wah, SBS, JP Hon Jasper TSANG Yok-sing, GBS, JP Hon Timothy FOK Tsun-ting, GBS, JP Members attending : Hon Albert HO Chun-yan Hon Martin LEE Chu-ming, SC, JP Hon Fred LI Wah-ming, JP Hon Mrs Selina CHOW LIANG Shuk-yee, GBS, JP Hon Emily LAU Wai-hing, JP Hon Andrew CHENG Kar-foo Hon Abraham SHEK Lai-him, JP Hon Tommy CHEUNG Yu-yan, JP Hon Audrey EU Yuet-mee, SC, JP Hon LEUNG Kwok-hung Dr Hon KWOK Ka-ki Hon Ronny TONG Ka-wah, SC Member absent : Hon Howard YOUNG, SBS, JP Public officers : Agenda Item I attending Mr John C TSANG, JP Secretary for Commerce, Industry and Technology - 2 - Mrs Marion LAI, JP Deputy Secretary for Commerce, Industry and Technology (Communications and Technology) Mr CHU Pui-hing, JP Director of Broadcasting Agenda Item II Mrs Marion LAI, JP Deputy Secretary for Commerce, Industry and Technology (Communications and Technology) Ms Lorna WONG Commissioner for Television and Entertainment Licensing Mr PO Pui-leong Assistant Commissioner for Television and Entertainment Licensing (Broadcasting) Attendance by : Agenda Item I invitation Radio Television Hong Kong Programme Staff Union Ms Janet MAK Lai-ching Chairperson Ms Echo WAI Pui-man Exco Member Clerk in attendance : Miss Polly YEUNG Chief Council Secretary (1)3 Staff in attendance : Ms Connie FUNG Assistant Legal Adviser 3 Ms Debbie YAU Senior Council Secretary (1)1 Ms Sharon CHAN Legislative Assistant (1)6 _________________________________________________________________ Action - 3 - I Broadcasting services of Radio Television Hong Kong LC Paper No. -

Six-Monthly Report on Hong Kong July-December 2005

Six-monthly Report on Hong Kong July-December 2005 Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs by Command of Her Majesty March 2006 Cm 6751 £ 6.00 © Crown copyright 2006 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and departmental logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified. Any enquiries relating to the copyright in this document should be addressed to the Licensing Division, HMSO, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ. Fax 010603 723000 or e-mail: [email protected] FOREWORD This is the eighteenth in a series of reports to Parliament on the implementation of the Sino-British Joint Declaration on the Question of Hong Kong. It covers the period from 1 July to 31 December 2005. During the reporting period, constitutional reform and progress towards full universal suffrage once again dominated the political debate in Hong Kong. The SAR Government put forward proposals to reform the methods to elect the Chief Executive in 2007 and Legislative Council in 2008. We considered these proposals offered an incremental step in the right direction. However, the Legislative Council rejected the proposals on 21 December. Nevertheless, the British Government remains firmly committed to democratisation in Hong Kong. We believe that Hong Kong should advance to a system of universal suffrage, as envisaged by the Basic Law, as soon as possible. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ EVERYDAY IMAGININGS UNDER the LION ROCK: an ANALYSIS of IDENTITY FORMATION in HONG KONG a Di

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ EVERYDAY IMAGININGS UNDER THE LION ROCK: AN ANALYSIS OF IDENTITY FORMATION IN HONG KONG A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in POLITICS by Sarah Y.T. Mak March 2013 The Dissertation of Sarah Y.T. Mak is approved: _______________________________ Professor Megan Thomas, Chair ________________________________ Professor Ben Read ________________________________ Professor Michael Urban ________________________________ Professor Lisa Rofel ______________________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Sarah Y.T. Mak 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ..................................................................................................................... v Abstract ...............................................................................................................................vi Acknowledgments.........................................................................................................viii CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................1 I. SETTING THE SCENE .......................................................................................................1 II. THE HONG KONG CASE ............................................................................................. 15 III. THEORETICAL STARTING POINTS ........................................................................... -

Prospects for Democracy in Hong Kong: China's December 2007

Order Code RS22787 January 10, 2008 Prospects for Democracy in Hong Kong: China’s December 2007 Decision Michael F. Martin Analyst in Asian Trade and Finance Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Summary The prospects for democratization in Hong Kong became clearer following a decision of the Standing Committee of China’s National People’s Congress (NPCSC) on December 29, 2007. The NPCSC’s decision effectively set the year 2017 as the earliest date for the direct election of Hong Kong’s Chief Executive and the year 2020 as the earliest date for the direct election of all members of Hong Kong’s Legislative Council (Legco). However, ambiguities in the language used by the NPCSC have contributed to differences in interpretation of its decision. According to Hong Kong’s current Chief Executive, Donald Tsang Yam-kuen, the decision sets a clear timetable for democracy in Hong Kong. However, representatives of Hong Kong’s “pro- democracy” parties believe the decision includes no solid commitment to democratization in Hong Kong. The NPCSC’s decision also established some guidelines for the process of election reform in Hong Kong, including what can and cannot be altered in the 2012 elections. Since China established the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) on July 1, 1997, there have been questions about when and how the democratization of Hong Kong will take place.1 At present, Hong Kong’s Chief Executive is selected by an “Election Committee” of 800 largely appointed people, and its Legislative Council (Legco) consists of 30 members elected by universal suffrage in five geographic districts and 30 members selected by 28 “functional constituencies” representing various important sectors. -

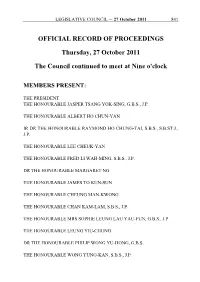

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 27

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 27 October 2011 841 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 27 October 2011 The Council continued to meet at Nine o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. 842 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 27 October 2011 THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE TIMOTHY FOK TSUN-TING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE AUDREY EU YUET-MEE, S.C., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, M.H. THE HONOURABLE LEE WING-TAT DR THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P. -

Key Events in 2009

20 KEY EVENTS IN 2009 May The Company was ranked first among the January benchmarked Hong Kong companies and March second among 50 listed companies in Asia The Company entered into a Principle in Environmental, Social Responsibility and Agreement for a Public-Private Partnership Governance by Responsible Research, an (PPP) project with Hangzhou Municipal independent research company. Government and Hangzhou Metro Group Pre-sales of the 2,169 units of Lake Silver, a Company Limited for the investment, property development in Wu Kai Sha, were construction and operations of Hangzhou launched in late May and over 90% of the Metro Line 1. units were sold. The Company signed a Concession Agreement with Shenyang Metro Group Company Limited and Shenyang Municipal Government for the operation and The Chief Executive of Hong Kong SAR, maintenance of Shenyang Metro Lines 1 Mr Donald Tsang, visited Majiapu Depot of Beijing and 2 for a term of 30 years. Metro Line 4 and officiated at the inaugural ceremony of the train integration test together with Mr Huang Wei, the Vice-Mayor of Beijing. The Company’s wholly-owned subsidiary, MTR The Company was awarded the concession Corporation (Shenzhen) Limited, formally signed rights to operate Sweden’s Stockholm the Concession Agreement with the Shenzhen Metro for eight years from November 2009 Municipal Government for the Build-Operate- with a possible six year extension. Transfer (BOT) Shenzhen Metro Line 4 project. Athletes of the Company won the The Hong Kong Management Championship in two Corporation Association awarded the Company Cups in the Green Power Hike, a Gold Prize in recognition of its which was held to promote a excellence and best practices in greener environment and staff training in the HKMA “Award healthy living.