Macquarie Law Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Macquarie a Smart Investment

Macquarie a smart investment Macquarie is Australia’s best modern university, so you’ll graduate with an internationally respected degree We adopt a real-world approach to learning, so our graduates are highly sought-after. CEOs worldwide rank Macquarie among the world’s top 100 universities for graduate recruitment Our campus is surrounded by leading multinational companies, giving you unparalleled access to internships and greater exposure to the Australian job market You will love the park-like campus for quiet study or catching up with friends among the lush green surrounds Investments of more than AU$1 billion in facilities and infrastructure ensure you have access to the best technology and facilities Our friendly, welcoming campus community is home to students from over 100 countries 2 MacquarIE UNIVERSIty Contents FACULTY OF ARTS 5 Media and creative arts 6 Security and intelligence 8 Society, history and culture 10 Macquarie Law School 14 FACULTY OF BUSINESS AND EcoNOMIcs 17 Business 18 MACQUARIE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT 22 FACULTY OF HumaN SCIENCEs 23 Education and teaching 24 Health sciences 29 Linguistics, translating and interpreting 32 Psychology 35 MEDICINE AND SURGERY 38 FACULTY OF SCIENCE 39 Engineering and information technology 40 Environment 42 Science 47 Higher degree research at Macquarie 50 How to apply: your future starts here 52 English language requirements 54 This is just the beginning: discover more 55 This document has been prepared by the The University reserves the right to vary Marketing Unit, Macquarie University. The or withdraw any general information; any information in this document is correct at course(s) and/or unit(s); its fees and/or time of publication (July 2013) but may the mode or time of offering its course(s) no longer be current at the time you refer and unit(s) without notice. -

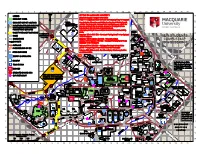

Campus Map New Students 2016 Session 1

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 A A B B C C D D NEW STUDENTS E CAMPUS MAP E 2016 SESSION 1 F F G G H H J J BIKE K HUB K L L BIKE HUB M M N N O O P BIKE P HUB Q Q R R S S T T U U V V W W 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 LOCATION GUIDE Telephone Switchboard: +61 2 9850 7111 General Email: [email protected] Web Site: mq.edu.au LOCATION BUILDING REF Cognitive Science S2.6 T14 ART GALLERY & MUSEUMS Graduation Unit C8A L3 N18 Emergency & First C1A S17 Institute of Early Childhood X5B L3 N10 Art Gallery E11A L1 H20 Higher Degree Research C5C L3 O17 Aid 9850 9999 Office Linguistics C5A L5 P16 Australian History Museum W6A 126 O12 Security & C1A S17 Hospital & Allied Health F8A L27 Psychology C3A L5 Q16 Biological Sciences Museum E8B L23 services Information Learning & Teaching Centre C3B P17 Student Connect C7A N15 School of Education C3A L8 Q16 Herbarium E8C L1 M23 Library C3C Q17 Macquarie E-Learning W6B 152 N12 IEC Art Collection X5B N10 Centre of Excellence Macquarie International E3A Q20 FACULTY OF ARTS W6A L1 O12 Lachlan Macquarie Room C3C Q17 Macquarie ICT C5B L0 O16 Arts Student Centre W6A L1 O12 Medical Centre & Clinic F10A L3 K26 Innovations Centre Museum of Ancient Cultures X5B 331 N10 Macquarie University X5A O9 METS (Macquarie F9B K24 Sporting Hall of Fame W10A J12 Engineering Technical Ancient History W6A 540 O12 Special Education Museum Services) Anthropology W6A 615 O12 MUSRA C10A L1 K17 FACULTY OF MEDICINE & HEALTH SCIENCES English -

Undergraduate Courses2020

Undergraduate courses 2020 When your potential is multiplied by a university built for collaboration, anything can be achieved. That’s YOU to the power of us At Macquarie, we have discovered the human equation for success. By knocking down the walls between departments, and uniting the powerhouses of research and industry, human collaboration can flourish. This is the exponential power of our collective, where potential is multiplied by a campus and curriculum designed to foster collaboration for the benefit of everyone. Because we believe when we all work together, we multiply our ability to achieve remarkable things. That’s YOU to the power of us 4 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE COURSES 2020 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE COURSES 2020 5 Contents MACQUARIE AT A GLANCE 6 MAKE YOUR DREAM CAREER A REALITY 10 PACE (PROFESSIONAL AND 12 COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT) GLOBAL LEADERSHIP PROGRAM 14 STUDENT EXCHANGE PROGRAM 16 GLOBAL LEADERS ON THE DOORSTEP 20 OUR CAMPUS 22 SUPPORT, SERVICES AND FLEXIBILITY 24 STUDENT ACCOMMODATION 26 MACQUARIE ENTRY 30 ADJUSTMENT FACTORS 32 CASH IN WITH A SCHOLARSHIP 34 WHAT CAN I STUDY? 36 FEES AND OTHER COSTS 40 HOW TO APPLY 41 LEARN THE LINGO 42 COURSES MADE BY (YOU)us 44 2019 CALENDAR OF EVENTS 106 Questions? Ask us anything … FUTURE STUDENTS Degrees, entry requirements, fees and general enquiries: • chat live by clicking on the chat icon on any degree page • ask us a question at [email protected] • call us on (02) 9850 6767. 6 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE COURSES 2020 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE -

Macquarie University at a Glance

Macquarie University at a glance CRICOS Number 00002J Macquarie at a glance • Established in 1964 • 1300 academic staff • 39,600 students • 9,000 international students • Top 2 per cent of universities globally • 156,000 alumni in more than 140 countries • Among the top 10 universities in Australia • Among the top 40 universities in Asia-Pacific CEOs worldwide rank Macquarie among the world’s top 100 universities for their graduate recruitment 2012 Global Employability Survey CEOs worldwide rank Macquarie among the world’s top 100 universities for their graduate recruitment 2012 Global Employability Survey Located 15 kms from the Sydney CBD Located 15 kms from the Sydney CBD Sydney is one of the 10 best cities in the world to live in The Economist Global Liveability Report, 2012 Living in Sydney MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY Find out why Enjoy Sydney’s the koalas and fantastic kangaroos at shopping, some Taronga Zoo of which is located have some right next to the of the most University in the amazing views Macquarie Centre in the world shopping complex Take a day trip Relax and to the world unwind on one heritage listed of Sydney’s Blue Mountains, 100 beaches, only 90 minutes including the away from world-famous Macquarie Bondi Beach Rankings and ratings MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY • has 5 QS stars in teaching, employability, research, internationalisation, facilities, innovation, access and specialist subjects • is ranked in the top 2% of universities globally • is among the top 10 universities in Australia • is among the top 40 universities in Asia-Pacific -

Undergraduate Courses2022

Undergraduate courses 2022 When your potential is multiplied by a university built for collaboration, anything can be achieved. That’s YOU to the power of us 2 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE COURSES 2022 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE COURSES 2022 3 At Macquarie, we have discovered the human equation for success. By knocking down the walls between departments, and uniting the powerhouses of research and industry, human collaboration can flourish. This is the exponential power of our collective, where potential is multiplied by a campus and curriculum designed to foster collaboration for the benefit of everyone. Because we believe when we all work together, we multiply our ability to achieve remarkable things. That’s YOU to the power of us Why Macquarie? DEGREES CO-DESIGNED WITH INDUSTRY Many of our degrees are co-designed with industry. This means they’re shaped by the latest industry trends and adjusted to respond to the real-time needs of industry. DEGREES WITH IN-BUILT INTERNSHIPS Practical experience is built into all of our degrees. So when you graduate, you’ll have the knowledge and skills you’ll need to meet the current and future challenges of your chosen profession. PERSONALISED DEGREES All universities offer double degrees, but we let you personalise your double degree by choosing the combination you consider will best kick-start your career. CAREER AND EMPLOYMENT SERVICE We can help you prepare a résumé, identify job opportunities, and connect you with employers and industry partners through our unique recruitment service. MULTIMODE STUDY As a Macquarie student, you have the option to undertake your degree on campus or online – or a combination of both. -

Volume 40, Number 1 the ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW Law.Adelaide.Edu.Au Adelaide Law Review ADVISORY BOARD

Volume 40, Number 1 THE ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW law.adelaide.edu.au Adelaide Law Review ADVISORY BOARD The Honourable Professor Catherine Branson AC QC Deputy Chancellor, The University of Adelaide; Former President, Australian Human Rights Commission; Former Justice, Federal Court of Australia Emeritus Professor William R Cornish CMG QC Emeritus Herchel Smith Professor of Intellectual Property Law, University of Cambridge His Excellency Judge James R Crawford AC SC International Court of Justice The Honourable Professor John J Doyle AC QC Former Chief Justice, Supreme Court of South Australia Professor John V Orth William Rand Kenan Jr Professor of Law, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Professor Emerita Rosemary J Owens AO Former Dean, Adelaide Law School The Honourable Justice Melissa Perry Federal Court of Australia Emeritus Professor Ivan Shearer AM RFD Sydney Law School The Honourable Margaret White AO Former Justice, Supreme Court of Queensland Professor John M Williams Dame Roma Mitchell Chair of Law and Former Dean, Adelaide Law School ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW Editors Associate Professor Matthew Stubbs and Dr Michelle Lim Book Review and Comment Editor Dr Stacey Henderson Associate Editors Charles Hamra, Kyriaco Nikias and Azaara Perakath Student Editors Joshua Aikens Christian Andreotti Mitchell Brunker Peter Dalrymple Henry Materne-Smith Holly Nicholls Clare Nolan Eleanor Nolan Vincent Rocca India Short Christine Vu Kate Walsh Noel Williams Publications Officer Panita Hirunboot Volume 40 Issue 1 2019 The Adelaide Law Review is a double-blind peer reviewed journal that is published twice a year by the Adelaide Law School, The University of Adelaide. A guide for the submission of manuscripts is set out at the back of this issue. -

Undergraduate Scholarships 20111 Letter from the Vice-Chancellor

Undergraduate Scholarships 20111 Letter from the Vice-Chancellor Access to good education can make a huge difference to your life and the life of your family and wider community. Being the first person in your family to go to university is possible — I know, I was that person in my family. Education provided me with many opportunities as I’m sure it has for many others. Opportunity and support make all the difference. Students from a variety of backgrounds continue to be under-represented in universities because circumstances work to deprive them of that opportunity and support. Through our exciting scholarship program, Macquarie University wants to ensure that equality of opportunity extends to everyone with the ability to benefit from higher education. If you think you can’t afford to study at Macquarie, come and talk to us. We have a strong commitment to supporting students who need financial assistance and have dedicated services to support you during your study. Professor Steven Schwartz Vice-Chancellor Macquarie University 2 Macquarie University Undergraduate Scholarships 2011 Merit, Education Costs and Accommodation Scholarships Macquarie University Merit Value: $12,000 per year for up to Letter from the Scholar Program – Aspiring five years. Professionals Program How to apply online: Vice-Chancellor Applications are open now at Aspiring Professionals Program, www.mq.edu.au/scholarships a new initiative for Merit Scholars, has been successfully launched in 2010. Closing Date: Applications close on Macquarie’s Merit Scholars are selected 30 November 2010. based on their academic achievements Notification Date: Applicants will and an ATAR of 98.5 or above at the HSC be advised of the outcome of their level (from 2010 HSC only). -

Free Speech 2014 Symposium Thursday, 7 August 2014 Aerial Function Centre, Sydney

Free Speech 2014 symposium Thursday, 7 August 2014 Aerial Function Centre, Sydney Starts Ends Theme Format Topic Speakers 08.00 08.50 Registrations 08.50 09.00 Speech Attendees asked to be seated Conference Chair: Jana Wendt 09.00 09.10 Presentation Welcome to country Aunty Norma Ingram - Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council 09.10 09.20 Speech Introductory remarks Professor Gillian Triggs - President, Australian Human Rights Commission Opening session 09.20 09.50 Keynote address Free speech reflections Senator the Hon George Brandis QC - Attorney-General 09.50 10.10 Speech Free speech stocktake Tim Wilson - Australian Human Rights Commissioner 10.10 10.30 Speech ALRC Inquiry into Freedoms Professor Rosalind Croucher - President, Australian Law Reform Commission 10.30 10.50 Morning tea Free speech in a liberal democracy Chris Berg - Director of Policy, Institute of Public Affairs Accommodating rights Speeches & Does defamation law deserve ridicule? Dr Roy Baker - Macquarie School of Law 10.50 11.55 (Session 1) questions Vilification laws Dr Augusto Zimmermann - School of Law, Murdoch University The commercial environment Dr Kesten Green - University of South Australia Business School Combating online harassment Dr Monika Bickert - Head of Global Content Policy, Facebook Free speech in the digital Speeches & 11.55 12.50 Reforming intellectual property Trish Hepworth - Australian Digital Alliance age questions Free speech & the internet Professor Julian Thomas - Swinburne Institute for Social Research 12.50 13.30 Lunch Dr Gary Johns -

Free Speech 2014

Free Speech 2014 SYMPOSIUM PAPERS Supporting sponsors Major sponsors The Australian Human Rights Commission encourages the dissemination and exchange of information provided in this publication. All material presented in this publication is provided under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia, with the exception of: • the Australian Human Rights Commission logo • photographs and images • any content or material provided by third parties. The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on the Creative Commons website, as is the full legal code for the CC BY 3.0 AU licence. Attribution Material obtained from this publication is to be attributed to the Australian Human Rights Commission with the following copyright notice: © Australian Human Rights Commission 2014. ISBN 978-1-921449-66-6 Free Speech 2014 • Symposium Papers Design and layout Dancingirl Designs Electronic format This publication can be found in electronic format on the website of the Australian Human Rights Commission: http://www.humanrights.gov.au/free-speech-2014 SYMPOSIUM PAPERS Australian Human Rights Commission 2014 everyone, everywhere, everyday Contents everyone, everywhere, everyday iii Message from the Commissioner 1 1 Opening session 2 1.1 Emeritus Professor Gillian Triggs 2 Topic: Free speech and human rights in Australia 2 1.2 Tim Wilson 4 Topic: Free speech stocktake 4 1.3 Professor Rosalind Croucher 6 Topic: ALRC Inquiry into Freedoms 6 1.4 Andrew Greste 10 Topic: The human cost of restricting free speech 10 2 Accommodating Rights (Session 1) 13 2.1 Chris Berg 13 Topic: Free speech in a liberal democracy 13 2.2 Dr Roy Baker 15 Topic: Does defamation law deserve ridicule? 15 2.3 Dr Augusto Zimmermann 17 Topic: Why free speech protects the weak, not the strong (and why the government’s backtrack on RDA section 18C compromises our ‘national unity’) 17 2.4 Dr Kesten C. -

Download PDF Read More

ALRC 2009–10 R E P O R T 113 ANNUAL REPORT Requests and inquiries regarding this report should be addressed to: The Executive Director Australian Law Reform Commission GPO Box 3708 Sydney NSW 2001 Telephone: (02) 8238 6333 Fax: (02) 8238 6363 Email: [email protected] This report is also accessible online at: www.alrc.gov.au ISBN 978-0-9807194-3-7 Print Post Approval Number: PP255003/02228 © Commonwealth of Australia 2010 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in whole or part, subject to acknowledgement of the source, for your personal, non- commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), all other rights are reserved. Requests for further authorisation should be directed to the Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Copyright Law Branch, Attorney-General’s Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Barton ACT 2600. Alternatively, an online request form is available at <www. ag.gov.au/cca>. Printed by Union Offset Printers ii Professor David Weisbrot AM ProfessorProfessor Rosalind David WeisbrotF Croucher AM PresPresidentident President The Honourable Robert McClelland MP The Honourable Philip Ruddock MP TheAttorney-General Honourable Philip Ruddock MP Attorney-General Attorney-GeneralParliament House Parliament House Parliament House CanberraCanberra ACT ACT 2600 2600 Canberra ACT 2600 2219 OctoberSeptember 2007 2010 19 October 2007 Dear Attorney-General Dear Attorney-General Dear Attorney-General On behalf of the members of the Australian Law Reform Commission, I am pleased to present the On behalf of the members of the Australian Law Reform Commission, I am pleased to present the Annual Report of the Australian Law Reform Commission for the period 1 July 2006 to 30 June Annual Report of the Australian Law Reform Commission for the period 1 July 2006 to 30 June 2007. -

Workplace Law Special Edition

LAW INSTITUTE JOURNAL INSTITUTE LAW OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH AND SAFETY | LEGAL FIRMS | EMPLOYMENT STATUS | WAGES | FAIR WORK ACT | EMPLOYEE PROTECTION MAY 2021 MAY 2021 WORKPLACE LAW SPECIAL EDITION WHY THE LAW SHOULD ALLOW FOR COMPULSORY TESTING IN A PANDEMIC WORKPLACE LAW SPECIAL EDITION • VACCINATION GUIDE • LEGAL FIRMS • EMPLOYMENT STATUS • WAGES • FAIR WORK ACT • EMPLOYMENT PROTECTION COVID-19 • BUSINESS POST-LOCKDOWN www.liv.asn.au/LIJ www.liv.asn.au/LIJ • ZOOMING INTO NEW JOBS HEALTH AND WELLBEING PP100007900 ISSN 0023-9267 PP100007900 ISSN 0023-9267 ACCENTUATE THE POSITIVE RRP $20 95.5 Successful law firms are agile Whether you’re at home or back in the office, LEAP lets you work with flexibility. On the go In the office In court At home leap.com.au/agile-law-firms Contents May 2021 WORKPLACE LAW SPECIAL EDITION FROM PAGE 22 Vaccination guide Legal firms Employment status Wages Fair Work Act Employment protection Law firms after COVID-19 How firms have adapted By Karin Derkley PAGE 11 Zooming into new jobs The challenge of starting a new role during the pandemic By Karin Derkley PAGE 15 Health and wellbeing Accentuate the positive By Megan Fulford PAGE 87 ADOBE STOCK MAY 2021 LAW INSTITUTE JOURNAL 1 Contents May 2021 workplace law special edition Protect the best interests FEATURES NEWS EVERY ISSUE 4 Contributors OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH AND SAFETY FIRMS 6 From the president Law firms after COVID-19 of your clients with 22 A shot in the arm 11 8 Unsolicited A COVID-19 vaccine has arrived but the The pandemic dealt an initial blow COURTS & PARLIAMENT pandemic's twists and turns are not over yet. -

Chapter 2 Freedom of Speech and Part IIA of the Racial

Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights Inquiry report Freedom of speech in Australia Inquiry into the operation of Part IIA of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) and related procedures under the Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986 (Cth) 28 February 2017 © Commonwealth of Australia 2017 ISBN 978-1-76010-526-6 PO Box 6100 Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Phone: 02 6277 3823 Fax: 02 6277 5767 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.aph.gov.au/joint_humanrights/ This document was prepared by the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights and printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Department of the Senate, Parliament House, Canberra. ii Membership of the committee Members Mr Ian Goodenough MP, Chair Moore, Western Australia, LP Mr Graham Perrett MP, Deputy Chair Moreton, Queensland, ALP Mr Russell Broadbent MP McMillan, Victoria, LP Senator Carol Brown Tasmania, ALP Senator Richard Di Natale (12.12.16) Victoria, AG Senator Sarah Hanson-Young (2.2.17) South Australia, AG Ms Madeleine King MP Brand, Western Australia, ALP Mr Julian Leeser MP Berowra, New South Wales, LP Senator Nick McKim Tasmania, AG Senator Claire Moore Queensland, ALP Senator James Paterson Victoria, LP Senator Linda Reynolds CSC Western Australia, LP Senator Rachel Siewert (3.2.17) Western Australia, AG Secretariat Ms Toni Dawes, Committee Secretary Ms Zoe Hutchinson, Principal Research Officer Ms Nicola Knackstredt, Principal Research Officer Mr Tasman Larnach, Principal Research Officer Mr Glenn Ryall, Principal Research Officer Ms Jessica Strout, Principal Research Officer Ms Eloise Menzies, Senior Research Officer Mr Josh See, Senior Research Officer Ms Morana Kavgic, Legislative Research Officer Ms Alice Petrie, Legislative Research Officer iii Table of contents Membership of the committee ......................................................................