North Magnetic Dip Pole (NMDP)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix A. Survival Strategies of the Ecotonal Species

Appendix A. Survival Strategies of the Ecotonal Species With greater numbers of species found in relatively high abundance in communities of both the boreal zone and the arctic regions, with fewer in the forest-tundra ecotonal communities, the question arises as to the strategies involved that permit adaptations to disparate environments yet prohibit all but a few from surviving in the ecotone, at least in numbers sufficient so they are recorded in quadrats of the size employed in transects of this study. There is a depauperate zone in the forest-tundra ecotone marked by a paucity of species, a zone in which only a relatively few wide-ranging species are persistently dominant (see Tables 5.1-5.9). Plant communities in both the forests to the south and the tundra to the north possess more species of sufficient abundance to show up in the transects. In the depauperate zone, there is no lack of vegetational cover over the landscape, but fewer species in total dominate the communities. There are fewer species demonstrating intermediate abundance, fewer rare species. The obvious question is, "Why should this be so?" As yet, there is perhaps no fully satisfactory answer, but there have been studies that at least seem to point the way for an approach to the question. Studies of the survival and reproductive strategies oftundra plants, arctic and alpine, have a long history, and these are thoroughly discussed in classic papers and reviews by Britton (1957), Jeffree (1960), Warren Wilson (1957a,b, 1966a,b, 1967), Johnson et al. (1966), Johnson and Packer (1967), Billings and Mooney (1968), Bliss (1956, 1958, 1962, 1971), Billings (1974), and Wiclgolaski et al. -

An Arctic Engineer's Story 1971 to 2006

An Arctic Engineer’s Story 1971 to 2006 by Dan Masterson To my wife Ginny and my sons, Andrew, Greg, and Mark ii Preface In 1971, I just happened to be in the right place at the right time. I had just completed my PhD and was looking for work. I was told to contact Hans Kivisild who had just been given a contract from an oil company to investigate an engineering issue in the Arctic. This started my career in Arctic engineering, just when the second major exploration phase was beginning in the western Arctic, 123 years after Franklin started the first phase of exploration in the area. This recent phase was also filled with individuals who were going “where few had gone before,” but unlike the earlier explorers, these recent explorers were accompanied by regulators, scientists and engineers who wanted to ensure that the environment was protected and also to ensure that the operations were carried out in the safest and most cost- efficient manner. Between about 1970 to 1995, several oil companies and Arctic consulting companies turned Calgary into a world leader in Arctic technology. It was a time that one could have an idea, check it out in small scale, and within a year or so, use it in a full-scale operation. During the next 25 years, industry drilled many wells in the Arctic using the technologies described in this book. In 1995, the oil industry pulled out of the Arctic mainly due to lack of government incentives and poor drilling results. In 2016, both the Canadian and United States governments declared a moratorium on Arctic drilling. -

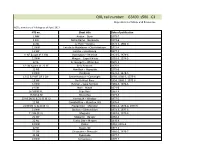

Canada Topographical

University of Waikato Library: Map Collection Canada: topographical maps 1: 250,000 The Map Collection of the University of Waikato Library contains a comprehensive collection of maps from around the world with detailed coverage of New Zealand and the Pacific : Editions are first unless stated. These maps are held in storage on Level 1 Please ask a librarian if you would like to use one: Coverage of Canadian Provinces Province Covered by sectors On pages Alberta 72-74 and 82-84 pp. 14, 16 British Columbia 82-83, 92-94, 102-104 and 114 pp. 16-20 Manitoba 52-54 and 62-64 pp. 10, 12 New Brunswick 21 and 22 p. 3 Newfoundland and Labrador 01-02, 11, 13-14 and 23-25) pp. 1-4 Northwest Territories 65-66, 75-79, 85-89, 95-99 and 105-107) pp. 12-21 Nova Scotia 11 and 20-210) pp. 2-3 Nunavut 15-16, 25-27, 29, 35-39, 45-49, 55-59, 65-69, 76-79, pp. 3-7, 9-13, 86-87, 120, 340 and 560 15, 21 Ontario 30-32, 40-44 and 52-54 pp. 5, 6, 8-10 Prince Edward Island 11 and 21 p. 2 Quebec 11-14, 21-25 and 31-35 pp. 2-7 Saskatchewan 62-63 and 72-74 pp. 12, 14 Yukon 95,105-106 and 115-117 pp. 18, 20-21 The sector numbers begin in the southeast of Canada: They proceed west and north. 001 Newfoundland 001K Trepassey 3rd ed. 1989 001L St: Lawrence 4th ed. 1989 001M Belleoram 3rd ed. -

High Arctic PEMT Layers

High Arctic PEMT Layers Table of Contents General Sensitivity Notes .............................................................................................................................. 3 Sensitivity Layers ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Grid Cell Sensitivity Rating ............................................................................................................................ 3 Polar Bear ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 Rationale for Selection .............................................................................................................................. 3 Key habitat ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Sustainability Factors ................................................................................................................................ 4 Susceptibility to Oil and Gas Activities ...................................................................................................... 5 Potential Effects of Climate Change ......................................................................................................... 5 Sensitivity Ranking ................................................................................................................................... -

Kivalliq Musk Ox Management Plan

Page 1 of 20 DRAFT MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR HIGH ARCTIC MUSKOXEN OF THE QIKIQTAALUK REGION 2012 – 2017 Prepared in collaboration with: NTI Wildlife, Resolute Bay HTO, Arctic Bay HTO, Grise Fiord HTO and the Qikiqtaaluk Wildlife Board Draft Management Plan for High Arctic Muskoxen of the Qikiqtaaluk Region Page 2 of 20 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 SUMMARY 2.0 THE QIKIQTAALUK MUSKOX POPULATION AND RANGE 2.1 Muskox Range 2.2 Communities that Harvest Muskoxen 3.0 THE NEED FOR A MUSKOX MANAGEMENT PLAN 4.0 ROLES OF CO-MANAGEMENT PARTNERS AND STAKEHOLDERS 4.1 Role of the Co-Management Partners 4.2 Role of the Communities 4.3 Inclusion of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit 5.0 QIQIKTAALUK MUSKOX MANAGEMENT PLAN 5.1 Goals of the Management Plan 5.2 Management Plan Priorities 5.3 Management Strategies 5.4 Herd Monitoring and Indicators 5.5 Muskox Management Units 6.0 Action Plans Appendix A - RECOMMENDATIONS Appendix B – ACTION PLAN Draft Management Plan for High Arctic Muskoxen of the Qikiqtaaluk Region Page 3 of 20 1.0 SUMMARY Prior to the enactment of protection in 1917 (Burch, 1977), muskox populations throughout the central Arctic were hunted to near extinction. Although limited information is available on the status of muskoxen in much of the eastern Mainland (Fournier and Gunn, 1998), populations throughout Nunavut are currently re-colonizing much of their historical range. Qikiqtaaluk harvesters have reported increased sightings of muskoxen in close proximity to their communities which indicates that the animals have expanded their ranges significantly over the last few decades. The Qikiqtaaluk Muskox Management Plan will serve as a tool to assist the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board (NWMB), the Qikiqtaaluk Wildlife Board (QWB), Government of Nunavut Department of Environment (DoE) and Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. -

Queen Elizabeth Islands Game Survey, 1961

•^i.ri.iri^VJU.HIJJ^^^iiH^ Queen Elizabeth Islands Game Survey, 1961 by JOHN S. TENER OCCASIONAL PAPERS No. 4 QUEEN ELIZABETH ISLANDS GAME SURVEY, 1961 by John S. Tener Canadian Wildlife Service Occasional Papers Number 4 National Parks Branch Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources Issued under the authority of the HONOURABLE ARTHUR LAING, P.C, M.P., B.S.A.. Minister of Northern Affairs and National Resources ROGER DUHAMEL, F.R.S.C. Queen's Printer and Controller oi Stationery, Ottawa, 1963 Cat. No. R 69-1/4 CONTENTS 5 ABSTRACT 6 INTRODUCTION 7 OBJECTIVE Personnel, 7 Itinerary, 7 8 METHOD Logistics, 8 Survey design, 8 Survey method, 9 Sources of error, 11 13 RESULTS Caribou and muskoxen on the Islands Devon, 14 Mackenzie King, 28 Cornwallis, 14 Brock, 29 Little Cornwallis, 15 Ellef Ringnes, 29 Bathurst, 15 Amund Ringnes, 30 Melville, 20 Lougheed, 31 Prince Patrick, 23 King Christian, 32 Eglinton, 26 Cornwall, 32 Emerald, 27 Axel Heiberg, 32 Borden, 27 Ellesmere, 33 38 SPECIES SUMMARY Avifauna American and Gyrfalcon, 40 black brant, 38 Peregrine falcon, 41 Snow geese, 39 Rock ptarmigan, 41 Old Squaw, 40 Snowy owl, 41 King eider, 40 Raven, 41 Mammalian fauna Polar bear, 42 Seals, 44 Arctic fox, 43 Peary caribou, 45 Arctic wolf, 44 Muskoxen, 47 49 SUMMARY 50 REFERENCES LIST OF TABLES I Survey intensity of the Islands, 13 II Calculations, estimated caribou population, Bathurst Island, 18 III Calculations, estimated muskox population, Bathurst Island, 19 IV Observations from the ground of four muskox herds, Bracebridge Inlet, -

Recent Trends in Abundance of Peary Caribou (Rangifer Tarandus Pearyi) and Muskoxen (Ovibos Moschatus) in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, Nunavut

Recent trends in abundance of Peary Caribou (Rangifer tarandus pearyi) and Muskoxen (Ovibos moschatus) in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, Nunavut Deborah A. Jenkins1 Mitch Campbell2 Grigor Hope 3 Jaylene Goorts1 Philip McLoughlin4 1Wildlife Research Section, Department of Environment, P.O. Box 400, Pond Inlet, NU X0A 0S0 2 Wildlife Research Section, Department of Environment, P.O. Box 400, Arviat NU X0A 0S0 3Department of Community and Government Services P.O. Box 379, Pond Inlet, NU X0A 0S0 4Department of Biology, University of Saskatchewan, 112 Science Place, Saskatoon, SK S7N 5E2 2011 Wildlife Report, No.1, Version 2 i Jenkins et al. 2011. Recent trends in abundance of Peary Caribou (Rangifer tarandus pearyi) and Muskoxen (Ovibos moschatus) in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, Nunavut. Department of Environment, Government of Nunavut, Wildlife Report No. 1, Pond Inlet, Nunavut. 184 pp. RECOMMENDATIONS TO GOVERNMENT i ABSTRACT Updated information on the distribution and abundance for Peary caribou on Nunavut’s High Arctic Islands estimates an across-island total of about 4,000 (aged 10 months or older) with variable trends in abundance between islands. The total abundance of muskoxen is estimated at 17,500 (aged one year or older). The estimates are from a multi-year survey program designed to address information gaps as previous information was up to 50 years old. Information from this study supports the development of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ)- and scientifically-based management and monitoring plans. It also contributes to recovery planning as required under the 2011 addition of Peary caribou to Schedule 1 of the federal Species At Risk Act based on the 2004 national assessment as Endangered. -

Submission to The

SUBMISSION TO THE NUNAVUT WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT BOARD FOR Information: Decision: X Issue: Management Plan for Peary Caribou in Nunavut Background: Peary caribou are currently listed as an endangered species under the Species at Risk Act. Regulations under the Wildlife Act are currently outstanding and there is no management regime in place for Peary caribou in Nunavut. The draft Management Plan for Peary Caribou in Nunavut (the plan, separate attachment) will serve as the basis for recommendations on new management units, Total Allowable Harvest (TAH), and future research and monitoring efforts. Previous attempts to determine appropriate management units and TAH for Peary caribou were unsuccessful. This effort is less prescriptive in terms of the size and number of proposed management units and the ability of Hunters and Trappers Organizations (HTOs) to have more involvement and say in the monitoring and management of Peary caribou. In addition to recommending management units and TAH levels the plan identifies a collaborative approach to long term monitoring. The Plan uses the information presented in the Department of Environment (DoE) report “Recent trends and abundance of Peary Caribou and Muskoxen in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, Nunavut,” (Jenkins et al., 2011) as a baseline to monitor future trends. Through community-based ground surveys that are conducted annually, but on a spatially cyclic basis, changes in herd status can be monitored. An annual meeting to discuss results and potential management recommendations will be used to target future survey efforts and in the event of observed declines or concerns of herd status, trigger further action which may include increased ground survey frequency or aerial surveys. -

Arctic Vol, 40, No, 4 (December 1987) P

ARCTIC VOL, 40, NO, 4 (DECEMBER 1987) P. 321-345 Forty Years of Arctic: The Journal of the Arctic Institute of North America ROMAN HARRISON’ and GORDON HODGSON’ (Received 6 August 1987; accepted in revised form 28August 1987) ABSTRACT. When the ArcticInstitute of North America was established in 1945as a membership institution, it was understood that the membership expected the Instituteto publish a journal. It appearedfor the first time in 1948, as Arctic, The Journal ofthedrcticlnstitute ofNorth America,and has been published continuouslyfor 40 years since then. It is now a leading academic journal publishing research papersfrom a variety of disciplines on a wide range ofsubjects dealing with theArctic. Over the 40 years it published40 volumes comprising123 1 research papers andother related material. The present study reports a content analysis of the 1231 papers revealing that trends over the last 40 years of research in the North were guided by the economic and academic pressuresof the dayfor northern research. The bulk of the papers in the 40 years involved three major areas: biologicalsciences, earth sciences and socialsciences. The proportion of research papers earthin sciences showed a decline, accompanied by a strong growth in biological science papers anda modest growth in social sciencepapers. Over the 40 years, subjects sited in the Canadian Arctic alwaysdominated, with a steady growth from 23% of thetotal papers per volume to 42%. In particular, significant increases in the numbers of papers in the last10 years came from resource-related work in the North, as well as from political, educational, cultural and sovereignty-relatedresearch. Research in the North leading to publication inArctic was conducted largelyby biologists andearth scientists. -

A.H. Joy (1887-1932)

558 ARCTIC PROFILES A.H. JOY (1887-1932) Inspector Alfred Herbert Joy of the Royal Canadian outcrops, archaeological sites, sites of historic interest, Mounted Police isbest known for a remarkable 1800-mile weather, and sea-ice conditions. His detailed remarks on (2900-km) patrol by dogsled across the heart of the Queen the numbers and migration of Peary caribou among the Elizabeth Islands in 1929. He had a keen interest in and Queen Elizabeth Islands and the long distances arctic extensive knowledge of the Arctic, its wildlife and people, hares can travel on their hind legs are of great biological and wasdedicated to upholding the law andjurisdiction of interest. He also foresaw new ways of patrolling the High Canada in isolated arctic regions. Arctic, stating:“It would be possible,if necessary, I believe, A.H. Joy was born in Maulden, eight miles south of to carry on an extensive survey of the islands west of Bedford, England on ,26 June 1887, where he attended Eureka sound by aeroplane.” He made important biologi- school, leaving the classroom in 1899 for work as a farm cal and archaeological collections for what is now the labourer. He then travelled to Canada, enlisting in the National Museumsof Canada. His collection of 700speci- Royal North-West Mounted Police on19 June 1909 after a mens froma Palaeo-Eskimo site was acknowledged by the short period of homesteading on the prairies. He rose Chief of the Division of Anthropology to be . “one of rapidly through the ranks: corporal in 1912, sergeant in the most valuableaccessions that the Division has received 1916, staff-sergeant in1921, and inspector in 1927. -

QUL Call Number: G3400 S500 .C3 Department of Mines and Resources

QUL call number: G3400 s500 .C3 Department of Mines and Resources NOTE: inventory of holdings as of April, 2013 NTS no. Sheet title Date of publication 1 NW Avalon – Burin 1978-7 2 SW Notre Dame – Bonavista 1972-6 11 NE La Poile – Burgeo 1973-3, 1980-4 11 NW Iles-de-la-Madeleine – Charlottetown 1973-4 11 SW Halifax – Louisbourg 1977-5 12 NE & part of 2 NW Harrington – Belle Isle 1973-5, 1979-6 12 NW Mingan – Cape Whittle 1953-3, 1974-5 12 SE St. George’s – White Bay 1976-5 12 SW & part of 22 SE Ile D’Anticosti 1975-3 13 NE Hamilton – Hopedale 1979-6 13 NW Naskaupi 1972-4, 1978-5 13 SE & PART OF 3 SW Battle Harbour – Cartwright 1958, 1968-5, 1975-6 13 SW North West River 1954, 1968-5, 1975-6 14 NW Hebron – Cape Territok 1969-5, 1974-6 14 SW Nain – Nutak 1974-6 16 NW & NE Cape Dyer 1967-4 16 SW & SE Hoare Bay 1977-5 20 NE (N ½) & 21 SE (S ½) Yarmouth – Windsor 1977-5 21 NE Campbellton – Moncton, NB 1976-4 21 NE (N ½) & 20 (S ½) Fredericton – Moncton 1961-3, 1973-4, 1977-5 21 NW Quebec – Edmundston 1973-3, 1977-6 21 SW (N ½) Megantic 1967-3, 1973-4 21 SW Megantic – Bangor 1950-2 22 NE Clarke City – Mingan 1978-9 22 NW Pletipi 1953, 1976-4 22 SE Gaspe, QC 1977-5 22 SW Chicoutimi – Rimouski 1966-5, 1976-7 23 NE Dyke Lake 1977-7 23 NW Caniapiscau 1979-7 23 NW Kaniapiskau 1958-5 23 SE Ashuanipi 1962-7, 1968-8, 1975-9 23 SW Nichicun 1958-4, 1975-6 24 NE George River 1960-5 24 NW Fort Chimo 1967-5, 1975-6 24 SE Indian House 1974-7 24 SW Fort McKenzie 1966-5, 1979-6 25 NW & NE Frobisher Bay 1971-5, 1979-6 25 SE Resolution Island 1968-4, 1979-5 -

Last Ice Area Greenland And

Last Ice Area Greenland and Canada Geoscience Resource Development Report Peter Adams, Consultant Prepared for WWF – Canada January, 2014 Melting sea ice near Axel Heiberg Island, Nunavut, July 2012. Source: Dr. Schroder-Adams, Carleton University. Report Last Ice Area Greenland and Canada – Geoscience Resource Development Report The report was prepared by Peter Adams, Consultant, for WWF. Published by WWF-Global Arctic Programme, 275 Slater Street, Suite 810, Ottawa, Ontario, K1P 5H9 Phone: +1 613 232 8706 The report can be downloaded from link ii Last Ice Area This is one of a series of research resources commissioned by WWF to help inform future management of the Area we call the Last Ice Area. We call it that because the title refers to the area of summer sea ice in the Arctic that is projected to last. As climate change eats away at the rest of the Arctic’s summer sea ice, climate and ice modellers believe that the ice will remain above Canada’s High Arctic Islands and above Northern Greenland for many more decades. Much life has evolved together with the ice. Creatures from tiny single celled organisms to seals and walrus, polar bears and whales, depend to some extent on the presence of ice. This means the areas where sea ice remains may become very important for ice-adapted life in future. One of my colleagues suggested we should have called the project the Lasting Ice Area. I agree, although it’s a bit late to change the name now, that name better conveys what we want to talk about.