Cassandra, Duchess of Chandos, As an Authority for Royal Progresses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Summer Events Broadmarsh Update And

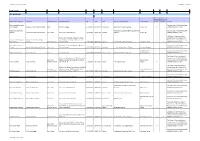

Paper Height 628.0mm Height Paper Y M C Y M C BB Y M C Y M C B YY M C B 20 B 40 B 80 B Y 13.0mm 13.0mm M −− 29 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−− 30 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−− 31 32 C B M Y M C B Y Y 20 Y 40 Y 80 M C 148.0 x 210.0mm x 148.0 210.0mm x 148.0 210.0mm x 148.0 B 210.0mm x 148.0 C Y M C B 12.0mm 12.0mm 12.0mm M 20 M 40 M 80 Y M C B Y M C B 6.0mm 6.0mm C 20 C 40 C 80 Y M C B Y M C B Y M C Y M C Y M −−−− 22 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−− 23 24 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−− 25 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−− 26 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−− 27 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−− 28 −−−−−−−−−−−−− Y M C BB Y M 148.0 x 210.0mm x 148.0 210.0mm x 148.0 210.0mm x 148.0 210.0mm x 148.0 C B 20 B 40 B 80 B Y M C 12.0mm 12.0mm 12.0mm B Lin+ Process YY M C B Y 80 12.0mm 12.0mm Paper Width 890.0mm 0/100% 1% 2% 3% 5% 10% 20% 25% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 75% 80% 90% 95% 97% 98% 99% Prinect CS−4i Format 102/105 Dipco 16.0d (pdf) © 2013 Heidelberger Druckmaschinen AG 0.5P 1P Times 2P Times 4P Times Times M 20 Times 4 P Times 2 P Times 1 P Times 0.5 P Y M −−−− 15 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−− 16 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−− 17 18 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−− 19 20 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−− 21 −−−−−−−−−−− C B C Y M C B 1/15 C 20 C 40 C 80 Y 148.0 x 210.0mm 148.0 x 210.0mm M 148.0 x 210.0mm 148.0 x 210.0mm C BB Y M 12.0mm 12.0mm 12.0mm C B Y M C Y M C V15.0i (pdf) Fujifilm Suprasetter Y Brillia LH−PJE C Plate Control Strip © Heidelberger Druckmaschinen AG 2013 Y M C B YY 6.0mm 6.0mm M C Summer 2019 DPI Acrobat Distiller 9.0.0 B 20 B 40 B 80 B Nottingham /mynottingham @mynottingham Y M C User: Heidelberg Druckmaschinen AG Liz.: 6EU240708 B Y Copyright Fogra 2008 Res.: 2400 M C B Y Y 20 Y 40 Y 80 −−−−−−−− 8 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−− -

Accreditation Scheme for Museums and Galleries in the United Kingdom: Collections Development Policy

Accreditation Scheme for Museums and Galleries in the United Kingdom: Collections development policy 1 Collections development policy Name of museum: Doncaster Museum Service Name of governing body: Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council Date on which this policy was approved by governing body: January 24th 2013 Date at which this policy is due for review: January 2018 1. Museum’s statement of purpose The Museum Service primarily serves those living in the Doncaster Metropolitan Borough area and those connected to the King‟s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry* and believes that its purpose can by summed up in four words : Engage, Preserve, Inspire, Communicate * The King‟s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry Museum has its own Collections Development Policy, but is included in the 2013-16 Forward Plan and therefore the Museum Service‟s statement of purpose. 2. An overview of current collections. Existing collections, including the subjects or themes and the periods of time and /or geographic areas to which the collections relate 2.0 At present (2012) the following collections have a member of staff with expertise in that particular field. Social History (including costume and photographs) Archaeology (Including Antiquities) World Cultures Fine and Decorative Arts Other collections are not supported by in-house expertise. For these we would actively look to recruit volunteers or honorary curators with knowledge relevant to these collections. We would also look to apply for grants to take on a temporary staff member to facilitate the curation of these collections. We would also look at accessing external expertise and working in partnership with other organisations and individuals. -

Cassandra Willoughby's Visits to Country Houses

Elizabeth Hagglund, ‘Cassandra Willoughby’s visits to country houses’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XI, 2001, pp. 185–202 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2001 CASSANDRA WILLOUGHBY’S VISITS TO COUNTRY HOUSES ELIZABETH HAGGLUND n , Cassandra Willoughby, a young woman of father and her late marriage, enabling her to travel I , began a series of journeys with her younger more widely than the majority of her contemporaries. brother Thomas. She recorded the details of her travels in a small notebook and continued to do so until , although after her marriage in her diary entries were largely restricted to a record of EARLY LIFE AND FAMILY moves between her husband’s estate in Edgware and Cassandra Willoughby was born at Middleton, their home in London. Warwickshire on April , the second child and The keeping of diaries and travel journals was only daughter of Francis Willoughby, by his wife, becoming fashionable at the time, and it was common formerly Emma Barnard. Her elder brother, Francis, for anyone travelling to record their impressions, had been born in ; her younger brother, even if they did so only for their own future Thomas, was born in . Middleton is near recollection. Books of instruction to travellers Tamworth, and the manor of Middleton had been in emphasised the importance of keeping records. The the family since . Middleton Hall, ‘a delicate and traveller ‘must alwayes have a Diary about him,’ wrote a delightful house’, according to Dugdale, is a James Howell, ‘when he is in motion of Iourneys ... medieval house, thinly classicised, and was the For the Penne maketh the deepest furrowes, and doth Willoughbys’ principal seat, although considerably fertilize, and enrich the memory more than anything less imposing than their secondary seat at Wollaton. -

Wollaton Hall I Jego Twórca Wollaton Hall and Its Creator

NAUKA SCIENCE Bartłomiej Gloger* Wollaton Hall i jego twórca Wollaton Hall and its creator Słowa kluczowe: Wollaton Hall, Robert Smythson, Key words: Wollaton Hall, Robert Smythson, Sir Francis Willoughby, angielski renesans, Sir Francis Willoughby, English Renaissance, architektura elżbietańska, Nottingham Elizabethan architecture, Nottingham LOKALIZACJA ZESPOŁU LOCATION PAŁACOWEGO OF THE PALACE Wollaton Hall leży na rozległej posesji otoczonej Wollaton Hall lies on a vast estate surrounded by niską zabudową mieszkaniową, która obecnie znajduje dwellings in a now suburban area 5 km west from the się w podmiejskiej strefi e miasta położonej 5 km na centre of Nottingham. The historic park was once con- zachód od centrum Nottingham. Zabytkowy park był nected to ancient village of Wollaton, sited at the foot niegdyś połączony z historyczną osadą Wollaton Village of a knoll on its north-west border. It is believed that leżącą na jego północno-zachodnim obrzeżu, u stóp at the end of 15th or early 16th century this area could dominującego wzgórza. Przypuszcza się, że pierwotnie have served as a common ground for the village. The teren ten, pod koniec XV w. lub na początku XVI w., historic sources, however rather unreliable, suggest that mógł służyć jako obszar wspólnoty gruntowej (common between 1492 and 1510 Sir Henry Willoughby fenced off grounds) należący do tej osady. Nieudokumentowane these grounds and attached them to his residence, most źródła sugerują, iż pomiędzy 1492 i 1510 r. Sir Hen- probably set nearby St. Leonard church. The park at that ry Willoughby przyłączył te tereny do siedziby rodu time could have been used to stock deer and to organise zlokalizowanej najprawdopodobniej w pobliżu kościoła hunting events. -

Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007

Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007 K - Z Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 A complete listing of all Fellows and Foreign Members since the foundation of the Society K - Z July 2007 List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 The list contains the name, dates of birth and death (where known), membership type and date of election for all Fellows of the Royal Society since 1660, including the most recently elected Fellows (details correct at July 2007) and provides a quick reference to around 8,000 Fellows. It is produced from the Sackler Archive Resource, a biographical database of Fellows of the Royal Society since its foundation in 1660. Generously funded by Dr Raymond R Sackler, Hon KBE, and Mrs Beverly Sackler, the Resource offers access to information on all Fellows of the Royal Society since the seventeenth century, from key characters in the evolution of science to fascinating lesser- known figures. In addition to the information presented in this list, records include details of a Fellow’s education, career, participation in the Royal Society and membership of other societies. Citations and proposers have been transcribed from election certificates and added to the online archive catalogue and digital images of the certificates have been attached to the catalogue records. This list is also available in electronic form via the Library pages of the Royal Society web site: www.royalsoc.ac.uk/library Contributions of biographical details on any Fellow would be most welcome. -

Huguenot Merchants Settled in England 1644 Who Purchased Lincolnshire Estates in the 18Th Century, and Acquired Ayscough Estates by Marriage

List of Parliamentary Families 51 Boucherett Origins: Huguenot merchants settled in England 1644 who purchased Lincolnshire estates in the 18th century, and acquired Ayscough estates by marriage. 1. Ayscough Boucherett – Great Grimsby 1796-1803 Seats: Stallingborough Hall, Lincolnshire (acq. by mar. c. 1700, sales from 1789, demolished first half 19th c.); Willingham Hall (House), Lincolnshire (acq. 18th c., built 1790, demolished c. 1962) Estates: Bateman 5834 (E) 7823; wealth in 1905 £38,500. Notes: Family extinct 1905 upon the death of Jessie Boucherett (in ODNB). BABINGTON Origins: Landowners at Bavington, Northumberland by 1274. William Babington had a spectacular legal career, Chief Justice of Common Pleas 1423-36. (Payling, Political Society in Lancastrian England, 36-39) Five MPs between 1399 and 1536, several kts of the shire. 1. Matthew Babington – Leicestershire 1660 2. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1685-87 1689-90 3. Philip Babington – Berwick-on-Tweed 1689-90 4. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1800-18 Seat: Rothley Temple (Temple Hall), Leicestershire (medieval, purch. c. 1550 and add. 1565, sold 1845, remod. later 19th c., hotel) Estates: Worth £2,000 pa in 1776. Notes: Four members of the family in ODNB. BACON [Frank] Bacon Origins: The first Bacon of note was son of a sheepreeve, although ancestors were recorded as early as 1286. He was a lawyer, MP 1542, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal 1558. Estates were purchased at the Dissolution. His brother was a London merchant. Eldest son created the first baronet 1611. Younger son Lord Chancellor 1618, created a viscount 1621. Eight further MPs in the 16th and 17th centuries, including kts of the shire for Norfolk and Suffolk. -

Collections for a History of Staffordshire, 1920-22

COLLECTIONS FOR A Staffordshire HISTORY OF STAFFORDSHIRE EDITED BY SampleCounty 1920 Studies “ Ana in thin undertaking, the Header m ay see what Furniture itlioag.i it I ,< disperst) nur Publick K»co. A. will afford for H i* try: nd how plentifully our own m ay be !u p p i« d an d l*p rw ^ tf p .ins rer t .aen thereir : t r w „at is W thert> made pub.m k, bath been coll“ “ “i;ih)e l{h° "‘ °i® ~ \nnals and they filled with few things but such as were very obvious, nay the Annalists them selves ( b ? & S S r^ d in e in Monasteries) too often,id byasstf wttr Interest and A ff.caon ^ T im ee and Persons * But on the contrary in our publick Records lye m atter of tact, in ful! Truth, an therewith the Chronological part, carried on, even to days of the M onth. So that an industnons Se art nr. m ay thenci ollect considerable m atter lor new H istory. rectiliem M y m istakes in our old and in both gratifie the world with unshadowed verity. — (ABHstoLES Hisstory of the Gm ter.) L O N D O N : HARRISON AND SONS, LTD., ST. MARTIN’S LANE. 1920. Staffordshire19SO. PRESIDENT. Thb Right Hon. t h e EARL OF DARTMOUTH, P.O., K.C.B., V.D. COUNCIL. Nominated by the Trustees of the William Salt Library. T h e R t. H o n . t h e LORD HATHERTON, C.M.G. S i r REGINALD HARDY, B a r t . -

L2 PDF Timetable

d A R R a LA L H D NE U 53 C S ad K o R N A The Vale . y Highbury L L e d L ll Phoenix Park R City A a Vale V R Hospital N O y N k A E a ut l r hall l at D W B i a e h y-p H f as h Cinderhill P ie N s r ld R . O d TT e V e I d e s NG d n u H n a A i DoubleTree o F t D o M R n A ROA C e RO h D n o d Nuthall Hotel ld t r EY o o o R LL o n n VA dtho V r is oo r W Ba W gn E A R e Get in touch... a R d Assarts ll . us N R N irc U oa O Farm C T d N H ad A Ro n y LocallinkDavid Lane L2 Morningto Cr E L NCN Basford e r y s L R le u l Woodthorpe . N a d b (Basford O V Roa s R y A O err Court e A A P L D m Hall) D For journey planning visit... A Lane Dulverton ill L2/X2 kh P S c gton Cres. to e in Vale S Changes to L2 timetable from 7th June 2021 include Nottingham Business Park, Glaisdale rn rc Sherwood W o S M N y in L c www.robinhoodnetwork.co.uk U AD hes L e Basford t t. -

Ncc Event Safety Risk Assessment

NCC EVENT SAFETY RISK ASSESSMENT WOLLATON PARK SITE OVERVIEW Wollaton Hall and Deer Park is located to the west of Nottingham City Centre within a designated conservation area. At the Centre of the Park is Wollaton Hall a Grade 1 listed building built in 1588, now containing a Natural History Museum. The adjacent stable block houses the Industrial Museum and public facilities including café, shop and toilet facilities. To the rear of the Hall is the formal gardens area featuring the Glass and Cast Iron Camelia House all the significant buildings with the estate are listed. The Park is a Wildlife haven with Red and Fallow Deer, various protected species including bats and badgers both in and around the stable block and the woodland areas. The historic parkland features tree avenues , paddocks and wetland areas, lake, golf course and areas of amenity grassland. The park also features a Ha Ha essentially an open ditch sites as to restrict access by the deer to certain areas including the formal gardens. The main entrance and exit to the park are off Wollaton Road with the Lime Tree Avenue entrance off the Ring Road used for vehicle access during large events. The day to day car park is of hard standing construction and is pay and display, with overspill parking adjacent to main drive and grassland areas used for major events. Entry to the park is over cattle grids and there is pedestrian access at numerous locations around the boundary. C:\Users\bwacb\Dropbox\AoC Sport Nat Champs 2017\Planning and preparation\Venues\Venue 1 Risk Assessments\Risk Assessment for Wollaton Park.docx SITE PLAN Car park Main Car Lime Tree Event/Area Showground park 1 Avenue area 2 The Lake Secondary Formal The Ha Ha Ha Ha showground Gardens C:\Users\bwacb\Dropbox\AoC Sport Nat Champs 2017\Planning and preparation\Venues\Venue 2 Risk Assessments\Risk Assessment for Wollaton Park.docx TYPES OF EVENTS HELD ON THIS SITE Pop concerts Static vehicles rallies Craft, flowers , dog shows Steam rallies Cross country runs / fun runs Commemorative / celebrity event e.g. -

ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Name (As On

Houses of Parliament War Memorials Royal Gallery, First World War ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Also in Also in Westmins Commons Name (as on memorial) Full Name MP/Peer/Son of... Constituency/Title Birth Death Rank Regiment/Squadron/Ship Place of Death ter Hall Chamber Sources Shelley Leopold Laurence House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Baron Abinger Shelley Leopold Laurence Scarlett Peer 5th Baron Abinger 01/04/1872 23/05/1917 Commander Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve London, UK X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Humphrey James Arden 5th Battalion, London Regiment (London Rifle House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Adderley Humphrey James Arden Adderley Son of Peer 3rd son of 2nd Baron Norton 16/10/1882 17/06/1917 Rifleman Brigade) Lincoln, UK MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) The House of Commons Book of Bodmin 1906, St Austell 1908-1915 / Eldest Remembrance 1914-1918 (1931); Thomas Charles Reginald Thomas Charles Reginald Agar- son of Thomas Charles Agar-Robartes, 6th House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Agar-Robartes Robartes MP / Son of Peer Viscount Clifden 22/05/1880 30/09/1915 Captain 1st Battalion, Coldstream Guards Lapugnoy, France X X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Horace Michael Hynman Only son of 1st Viscount Allenby of Meggido House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Allenby Horace Michael Hynman Allenby Son of Peer and of Felixstowe 11/01/1898 29/07/1917 Lieutenant 'T' Battery, Royal Horse Artillery Oosthoek, Belgium MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Aeroplane over House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Francis Earl Annesley Francis Annesley Peer 6th Earl Annesley 25/02/1884 05/11/1914 -

List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007

Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007 A - J Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 A complete listing of all Fellows and Foreign Members since the foundation of the Society A - J July 2007 List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 The list contains the name, dates of birth and death (where known), membership type and date of election for all Fellows of the Royal Society since 1660, including the most recently elected Fellows (details correct at July 2007) and provides a quick reference to around 8,000 Fellows. It is produced from the Sackler Archive Resource, a biographical database of Fellows of the Royal Society since its foundation in 1660. Generously funded by Dr Raymond R Sackler, Hon KBE, and Mrs Beverly Sackler, the Resource offers access to information on all Fellows of the Royal Society since the seventeenth century, from key characters in the evolution of science to fascinating lesser- known figures. In addition to the information presented in this list, records include details of a Fellow’s education, career, participation in the Royal Society and membership of other societies. Citations and proposers have been transcribed from election certificates and added to the online archive catalogue and digital images of the certificates have been attached to the catalogue records. This list is also available in electronic form via the Library pages of the Royal Society web site: www.royalsoc.ac.uk/library Contributions of biographical details on any Fellow would be most welcome. -

Enjoy Nottingham This Christmas!

Winter 2017/18 /mynottingham @mynottingham /mynottingham Enjoy Nottingham this Christmas! Ice rink, pantos and lots of festive family events Welcome to the latest issue of the Arrow, To comment, the City Council’s magazine for residents. compliment As the cold winter nights draw in, or complain: “it’s more important than ever that no one in Nottingham is without a Go online: proper place to sleep. www.nottinghamcity.gov.uk/hys That’s why we continue to fund our ‘No Second Textphone or minicom: 18001, then 0115 915 5555 Night Out’ policy which is helping to ensure that no one need sleep rough in Nottingham this winter. To do this, we fund and work with charities, churches Phone us on: 0115 915 5555 and other agencies to make sure there are enough beds for anyone who would otherwise be sleeping Visit us: on the streets. at any Council reception point or office You can find more information on page three Write to: Have Your Say, opposite about the support being provided in Nottingham City Council, Loxley House, Working together Nottingham to tackle homelessness and also Station Street, Nottingham NG2 3NG a phone number to contact the city’s Street The music community of Outreach team if you see someone who appears on rough sleeping Nottingham is coming together to present a one-day charity to be sleeping rough and might need help finding Arrowonline The City Council is once again working together with partners festival to raise vital funds to accommodation and support with any other needs If you’d rather read the Arrow support homeless people in online, scan the QR code on the across the city to provide support for rough sleepers this winter.