Evaluation of Phase 1 City Strategy Anne E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Wednesday Volume 583 2 July 2014 No. 17 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Wednesday 2 July 2014 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2014 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 873 2 JULY 2014 874 Scotland’s economy, and jobs for the people of Scotland House of Commons that come from inward investment—instead of a referendum distraction. Wednesday 2 July 2014 John Thurso (Caithness, Sutherland and Easter Ross) (LD): My right hon. Friend will be well aware that marine renewable energy presents a considerable The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock opportunity for inward international investment as well as for export, based on the knowledge we have acquired. In that regard, it is vital that MeyGen’s project goes PRAYERS ahead. What discussions has he had with either the Department of Energy and Climate Change or the Crown Estate to enable that to happen? [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] Mr Carmichael: I have had a number of discussions, as I think my hon. Friend is aware, involving my colleagues in DECC and in the Crown Estate. I am very keen to Oral Answers to Questions ensure that no procedural difficulties will stand in the way of the development from MeyGen, which, as he and I both know, is a very exciting and potentially lucrative development for his area. SCOTLAND Angus Robertson (Moray) (SNP): Inward investment The Secretary of State was asked— into Scotland is at a 16-year high under a Scottish International Inward Investment National party Government and in the run-up to an independence referendum. -

Queens Market: Rhyl Transport Statement September 2020

Queens Market: Rhyl Transport Statement September 2020 Mott MacDonald Ground floor Royal Liver Building Pier Head Liverpool L3 1JH United Kingdom T +44 (0)151 482 9910 mottmac.com Ion Developments Queens Market: Rhyl Transport Statement September 2020 Mott MacDonald Limited. Registered in England and Wales no. 1243967. Registered office: Mott MacDonald House, 8-10 Sydenham Road, Croydon CR0 2EE, United Kingdom Mott MacDonald | Queens Market: Rhyl Transport Statement Issue and Revision Record Revision Date Originator Checker Approver Description A 3rd August 2020 JMc KB DC DRAFT B 10th September 2020 JMc KB DC FINAL C 11th September 2020 JMc KB DC FINAL Document reference: 399989 | 001 | C Information class: Standard This document is issued for the party which commissioned it and for specific purposes connected with the above- captioned project only. It should not be relied upon by any other party or used for any other purpose. We accept no responsibility for the consequences of this document being relied upon by any other party, or being used for any other purpose, or containing any error or omission which is due to an error or omission in data supplied to us by other parties. This document contains confidential information and proprietary intellectual property. It should not be shown to other parties without consent from us and from the party which commissioned it. This r epo rt h as b een pre par ed s olely fo r us e by the par ty which co mmissio ned i t (t he ‘Clien t’) in conn ectio n with t he c aptio ned pr oject. -

At a Meeting of the FINANCE and GENERAL

At a Meeting of the FINANCE AND GENERAL PURPOSES COMMITTEE held on Wednesday 4th December 2013, at the Civic Offices, Wellington Road Community Centre, Rhyl commencing at 6.00pm. PRESENT Councillor P. Prendergast (Chair) Councillors B. Blakeley, Mrs J. Chamberlain-Jones, Mrs E. M. Chard, Ms J. Hughes, A. R. James, Mrs M. McCarroll, Mrs W. M. Mullen-James, S. H. Ratcliffe, A. J. Rutherford, D. Simmons and Miss C. L. Williams. Mr G. J. Nickels - Town Clerk Mr R. A. Hughes – Finance Officer Miss H. J. Windus - Personal Assistant & Secretary 100. APOLOGIES Apologies for non-attendance were received on behalf of Councillors Mrs J. Butterfield MBE (other commitment), Mrs P. M. Jones (family commitment), B. Mellor (indisposed) and Miss R. Siddall (family commitment). 101. RHYL AND PRESTATYN FUNTIME BROCHURE – NORTH EAST WALES BRAND The Mayor and the Town Clerk presented their report (circulated with Agenda) following their meeting with Denbighshire County Council officers in respect of the discontinuation of the above publication along with the Borderlands brochure, and advised that they both raised objections to the move and to the newly designated ‘North East Wales’ tourism area and publication, which would replace both. The Town Clerk added that the decision had been taken by the North Wales Tourism Partnership and not Denbighshire County Council. The Mayor felt that the move would leave Denbighshire’s main tourist spots, including Rhyl and Prestatyn lost amid the larger catchment area, which might have a detrimental effect on the number of visitors attracted to the towns. On behalf of a Member not present, the Town Clerk sought Members’ views on inviting an organisation called ‘British Destinations’ to give a presentation to a future Council meeting to explore any possibilities for Rhyl and Prestatyn with them. -

Contract Leads Powered by EARLY PLANNING Projects in Planning up to Detailed Plans Submitted

Contract Leads Powered by EARLY PLANNING Projects in planning up to detailed plans submitted. PLANS APPROVED Projects where the detailed plans have been approved but are still at pre-tender stage. TENDERS Projects that are at the tender stage CONTRACTS Approved projects at main contract awarded stage. Plans Submitted for solar farm Client: Yard, Wolverton Mill, Milton Keynes, Detail Plans Granted for supermarket/ Homes Ltd Agent: Jackson Design Detail Plans Granted for 6 offices/shops/ SETTLE £0.75M Plans Granted for waste transfer station Burnthouse Solar Limited Agent: The Abbey Buckinghamshire, MK12 5NW Tel: 01908 restaurant/take away Client: St Modwen Associates, Latimer House, Latimer Way, restaurants/cafes/pubs/takeaways units Land Off, 10 Lords Close Giggleswick building (extension) Client: Roy Hatfield Ltd MIDLANDS/ Group (Cambridgeshire) Ltd, Nene Lodge, 305246 Developments Ltd Developer: Stephen Sherwood Energy Village, Ollerton, Newark, Client: Neptune Developments Ltd Agent: Planning authority: Craven Job: Approval Of Developer: Thinking Buildings Limited, Funthams Lane, Whittlesey, Peterborough, COVENTRY £1.3M George & Partners, 170 London Road, Nottinghamshire, NG22 9QW Contractor: Austin-Smith:Lord, Port of Liverpool Building, Reserved Matters for 10 houses Client: R N Water Lane, Wirksworth, Matlock, Derbyshire, EAST ANGLIA Cambridgeshire, PE7 2PB Tel: 01733 200908 Batleys Plc, Gielgud Way Cross Point Leicester, LE2 1ND Tel: 0116 247 0557 Radleigh Homes Ltd, Pride Park, 5 Riverside Pier Head, Liverpool, Merseyside, L3 1BY -

The Record of Proceedings

Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru The National Assembly for Wales Cofnod y Trafodion The Record of Proceedings Dydd Mercher, 21 Medi 2011 Wednesday, 21 September 2011 21/09/2011 Cynnwys Contents 3 Cwestiynau Cyllid i’r Gweinidog Cyllid ac Arweinydd y Tŷ Finance Questions to the Minister for Finance and Leader of the House 24 Cwestiynau i’r Gweinidog Busnes, Menter, Technoleg a Gwyddoniaeth Questions to the Minister for Business, Enterprise, Technology and Science 46 Cynigion i Ethol Aelodau i Bwyllgorau Motions to Elect Members to Committees 48 Dadl y Ceidwadwyr Cymreig: Hygyrchedd Trafnidiaeth Gyhoeddus Welsh Conservatives Debate: The Accessibility of Public Transport 78 Dadl Plaid Cymru: Cyllid Plaid Cymru Debate: Funding 109 Dadl y Ceidwadwyr Cymreig: Llywodraeth Leol Welsh Conservatives Debate: Local Government 139 Cyfnod Pleidleisio Voting Time 154 Dadl Fer: Yr Asiantaeth Cynnal Plant—Yr Angen am Newid Short Debate: The Child Support Agency—The Need for Change Yn y golofn chwith, cofnodwyd y trafodion yn yr iaith y llefarwyd hwy ynddi yn y Siambr. Yn ogystal, cynhwysir cyfieithiad Saesneg o gyfraniadau yn y Gymraeg. In the left-hand column, the proceedings are recorded in the language in which they were spoken in the Chamber. In addition, an English translation of Welsh speeches is included. 2 21/09/2011 Cyfarfu’r Cynulliad am 1.30 p.m.gyda’r Llywydd (Rosemary Butler) yn y Gadair. The Assembly met at 1.30 p.m.with the Presiding Officer (Rosemary Butler) in the Chair. The Presiding Officer: Good afternoon. Y Llywydd: Prynhawn da. Cwestiynau Cyllid i’r Gweinidog Cyllid ac Arweinydd y Tŷ Finance Questions to the Minister for Finance and Leader of the House Amgylchedd a Datblygu Cynaliadwy Environment and Sustainable Development 1. -

Word 1 Introduction 2 Understanding the Improvement Plan 3

AGENDA ITEM NO. 2 [CABINET 2003 - 46] CABINET Minutes of the Cabinet meeting held in the Sculpture Gallery, Bodelwyddan Castle, Bodelwyddan on Tuesday 29 April 2003 at 10.00 a.m. PRESENT Councillors E C Edwards, Lead Member for Safeguarding our Communities; R W Hughes, Lead Member for Lifelong Learning; G M Kensler, Lead Member for Promoting Denbighshire; D M Morris, Lead Member for Communications; E A Owens, Lead Member for Finance; J A Smith, Lead Member for Social Inclusion; W R Webb, Lead Member for Property and Asset Management and E W Williams, Leader and Member for Economic Wellbeing. Observers: Councillors S Drew; M M Jones; R E Jones and N Hugh Jones. ALSO PRESENT Chief Executive; Deputy Chief Executive / Corporate Director: Resources; Financial Controller and the County Clerk. APOLOGIES Councillors P A Dobb, Lead Member for Health and Wellbeing and Councillor M A German, Lead Member for Sustainable Development and Environment. ANNOUNCEMENT The Deputy Leader welcomed to the meeting Andrea Garcia Balda, a Spanish student on the Leonardo da Vinci programme working in the Resources Directorate for two months. 1 URGENT MATTERS Item 9 Brondyffryn Trust, Denbigh - to be considered in Part II. Item 15A Community Fund Capital Bid. 1 2 MINUTES OF THE CABINET [CABINET 2003 - 46] The Minutes of the Cabinet meeting held on 25 March 2003 were submitted. Item 4 Best Value Review of Residential Homes: Councillor E A Owens asked that her concerns regarding releasing the requisite £1m be included as part of the penultimate paragraph. Councillor G M Kensler asked that the TUPE regulations being likely to change be added to her comments in the third paragraph. -

A Brand New Retail & Leisure Development

A BRAND NEW RETAIL & LEISURE DEVELOPMENT RAILWAY STATION RHYL E AV NE UR BO ST A548 WE VE MARINE LAKE A W AM EL NH LIN DE GT SY ON RO AD AN EXCITING RETAIL & W EST PAR LEISURE DEVELOPMENT ADE ET RE ST Y UA Q Marina Quay is a highly desirable new retail and leisure development located at the heart of the Rhyl, which benefits from: A548 A highly prominent location on the main arterial gateway into Rhyl 15 minute walk from Rhyl Railway Station 700 car parking spaces with excellent vehicular access from the A548, Quay Street and West Parade Local catchment of 150,801 within a 20km radius (focus, 1994) Attractive outlook over Marina Lake and the sea front in a popular tourist town Flexible opportunities to fit occupiers specific requirements. PLANNING Outline planning permission has been secured for: sq ft Food Store (A1) 74,822 sq ft Retail/Leisure (A1,A3,D2) 39,097 sq ft Drive Thru 3,272 sq ft Coffee Unit 2,002 sq ft Hotel 62 Bed Public House 7,470 sq ft PROJECT DRAWN BY DATE DRAWN Ocean Plaza Rhyl RS 31-10-13 Tower Works · Globe Road · Leeds · LS11 5QG [email protected] · Tel: 0113 880 0510 · Fax: 0113 880 0511 DRAWING TITLE DRAWING NUMBER Image 1 08215 - P280 This drawing is indicative only. This drawing is copyright and must not be reproduced without consent of NW Architects Limited. M57 LOCATION Rhyl is a popular North Wales M62 LIVERPOOL seaside resort town with a resident WIRRAL population of 25,000 and is located M53 11 miles East of Colwyn Bay and A548 PRESTATYN RIVER DEE 7 miles West or Prestatyn. -

High Street Rhyl LL18 1TR

High Street Rhyl LL18 1TR High Yielding Retail Investment High Street Investment Summary Rhyl, LL18 1TR • Let to the strong covenant of British Heart Foundation • Current Rental Income £45,000 per annum • Newly Fitted • Seeking offers in excess of £430,000, an attractive net initial • Prime Prominent Building in the Centre of Rhyl yield of 10%, assuming purchasers costs of 4.96%. High Yielding Retail Investment High Street Rhyl, LL18 1TR High Yielding Retail Investment 5 2 5 A 3 4 11 1 2 5 6 10 9 8 1 White Rose Shopping Centre 7 2 High Street 3 Matalan 4 Bus Station 5 Rhyl Railway Station 6 Morrisons 7 Drift Park Water Play Area 8 VUE Cinemas 9 Childrens Vilage Fairground 10 SeaQuarium Rhyl 11 Rhyl Events Area High Street Location Rhyl, LL18 1TR Rhyl is a popular seaside town and tourist centre and is the largest town in Denbighshire. It is situated on the North Wales coast some 40 miles north west of Wrexham, 34 miles west of Chester and 12 miles east of Colwyn Bay. The town has a population is 25,149 with some 76,150 living within 6 miles and 150,800 within 12 miles. The town has good communications with the A55 North Wales Expressway providing direct access to North West Wales, Chester and the national motorway network. There are regular direct train services to Holyhead (with links to Ireland), Chester, Manchester and London Euston. Rhyl is an established holiday destination and attracts some 3 High Yielding Retail Investment million visitors annually. Rhyl is currently undergoing significand redevelopment and investment. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Communities Scrutiny Committee, 25/10/2018 10:00

Public Document Pack To: Members of the Communities Date: 19 October 2018 Scrutiny Committee Direct Dial: 01824 712554 e-mail: [email protected] Dear Councillor You are invited to attend a meeting of the COMMUNITIES SCRUTINY COMMITTEE to be held at 10.00 am on THURSDAY, 25 OCTOBER 2018 in the COUNCIL CHAMBER, COUNTY HALL, RUTHIN. Yours sincerely G. Williams Head of Legal, HR and Democratic Services AGENDA PART 1 - THE PRESS AND PUBLIC ARE INVITED TO ATTEND THIS PART OF THE MEETING 1 APOLOGIES 2 DECLARATION OF INTERESTS Members to declare any personal or prejudicial interests in any business identified to be considered at this meeting. 3 URGENT MATTERS AS AGREED BY THE CHAIR Notice of items which, in the opinion of the Chair, should be considered at the meeting as a matter of urgency pursuant to Section 100B(4) of the Local Government Act 1972. 4 MINUTES (Pages 7 - 14) To receive the minutes of the Communities Scrutiny Committee held on 6 September 2018 (copy attached). 5 PROPOSED NEW WASTE AND RECYCLING SERVICE DESIGN (Pages 15 - 110) To consider a joint report by the Head of Highways & Environment and Waste and Recycling Manager (copy attached) on the proposed new Waste and Recycling Service together with feedback and engagement activity undertaken to inform the proposal. 10.10 a.m. – 11.00 a.m. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ BREAK ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ 6 TOURISM PROGRESS REPORT (Pages 111 - 178) To consider a report by the Team Leader: Tourism, Marketing and Events (copy attached) detailing progress achieved to date with various tourism initiatives and their contribution towards delivering the Council’s overall ambition in relation to economic development and seeking members’ views thereon. -

CYNGOR Sir Ddinbych Denbighshire COUNTY COUNCIL

CYNGOR Sir Ddinbych Denbighshire COUNTY COUNCIL _______________________________________________ MINUTES of Council and Committee Proceedings for the period 16 January 2001 - 27 March 2001 _______________________________________________ THE MINUTES VOLUME This volume contains the minutes of the following Committees and Sub-Committees:- Page Nos. Joint Agricultural Board of Denbighshire and Flintshire ... 23 October 2000 .......... 443 - 445 Joint Agricultural Board of Denbighshire and Flintshire ... 20 November 2000 .......... 446 - 447 Childrens and Residential Care Homes Panel ................. 4 January 2001 .......... 448 - 450 Corporate Health Safety and Welfare Panel ................... 9 January 2001 .......... 451 - 456 Cabinet ............................................................................. 9 January 2001 .......... 457 - 460 Special Resources Scrutiny Committee ........................... 12 January 2001 .......... 461 - 462 *Council ............................................................................ 16 January 2001 .......... 463 - 469 Audit ................................................................................. 17 January 2001 .......... 470 - 471 Cabinet ............................................................................. 23 January 2001 .......... 472 - 479 Lifelong Learning Scrutiny Committee .............................. 23 January 2001 .......... 480 - 484 Environment Scrutiny Committee .................................... 24 January 2001 .......... 485 - 489 Personal Services -

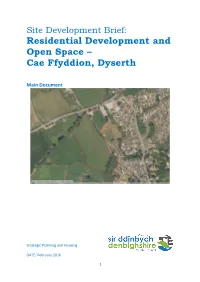

Residential Development and Open Space Cae Ffyddion Dyserth

Site Development Brief: Residential Development and Open Space – Cae Ffyddion, Dyserth Main Document Strategic Planning and Housing DATE: February 2016 1 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Document Status and Stages in Preparation 3. Site Location and Description 4. Planning Policies 5. Site Appraisal and Requirements 6. Design Principles 7. Contacts 8. Sources Appendices 1 Highway Access Design 2 Education Contributions Formula Fig 1 Site Location Fig 2 Relevant LDP Policies Fig 3 Flood Map Cover Photo: ‘Dyserth’ (Aerial View, 2009) 2 Figure 1: Location of Cae Ffyddion, Dyserth Development Site 3 1. Introduction 1.1 This site development brief is one of a series of Supplementary Planning Guidance notes amplifying Denbighshire Local Development Plan 2006 – 2021 (LDP) policies or principles of development for individual site allocations in a format which aims to guide the process, design and quality of new development. These notes are intended to offer detailed guidance to assist members of the public, Members of the Council, potential developers and Officers in discussions prior to the submission of and, consequently, in determination of future planning applications. 2. Document Status and Stages in Preparation 2.1 This site development brief was formally adopted by Denbighshire County Council’s Planning Committee on 17th February 2016. 2.2 The Council’s Supplementary Planning Guidance notes (SPGs) are not part of the adopted local development plan. The Welsh Government (WG) has confirmed that following public consultation and subsequent Local Planning Authority (LPA) approval, SPGs can be treated as a material planning consideration when LPAs, Planning Inspectors and the Welsh Government determine planning applications and appeals. -

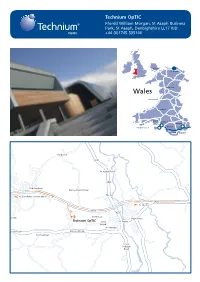

Technium Optic Map.Pdf

Technium OpTIC Ffordd William Morgan, St Asaph Business Park, St Asaph, Denbighshire LL17 0JD +44 (0)1745 535100 Bangor St. Asaph Dolgellau Wales Aberystwyth Lampeter Llanelli Swansea Cwmbran Baglan Pembroke Dock M4 Pencoed Cardiff Pengwern A525 St. Asaph Road A525 Bodelwyddan Nant-y-Faenol Road (A55) 25 ➣ The Roe to Llandudno / North Wales (A55) 26 to Chester 27 ➣ (A55) A525 Cwttir Lane Engine Hill High Street Technium OpTIC Heol St. Asaph Esgob Bro Havard Glascoed Road Glascoed Road Pentre-Mawr Lower Denbigh Road Technium OpTIC Ffordd William Morgan, St Asaph Business Park, St Asaph, Denbighshire LL17 0JD +44 (0)1745 535100 By Car By Rail From the West Train tickets can be purchased online at From the A55, exit at junction 26 to St www.thetrainline.com Asaph Business Park (Parc Busnes Llanelwy). For train info and journey planning visit At the first roundabout, c 400m take the www.nationalrail.co.uk or call National Rail 3rd exit. Enquiries: 08457 48 49 50 Technium OpTIC is on your left. From Rhyl Railway Station, take a taxi from outside to the office. Journey time is From the East / England approximately 10 minutes. From M53 or M56 join the A55. By Air Exit the A55 at junction 26 to St Asaph Business Park (Parc Busnes Llanelwy). From Manchester International Airport, Technium OpTIC is approximately 1 hours At the first roundabout c 400m take the drive away. 3rd exit. From Liverpool John Lennon International Technium OpTIC is on you left. Airport, Technium OpTIC is approximately From the South 1 hours drive away. From the Midlands and South Wales, continue on the A5.