Jogakusei: a Cultural Icon of Meiji Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapping the Interior Frontier of Japanese Settlers in Colonial Korea

The Journal of Asian Studies Vol. 70, No. 3 (August) 2011: 706–729. © The Association for Asian Studies, Inc., 2011 doi:10.1017/S0021911811000878 A Sentimental Journey: Mapping the Interior Frontier of Japanese Settlers in Colonial Korea JUN UCHIDA This article explores the role of affect and sentiment in shaping cross-cultural encounters in late colonial Korea, as seen and experienced through the eyes of Japanese men and women who grew up in Seoul. By interweaving the oral and written testimonies of former settlers who came of age on the peninsula between the late 1920s and the end of colonial rule in 1945, the paper attempts to reconstruct their emotional journey into adulthood as young offspring of empire: specifically, how they apprehended colonialism, what they felt when encountering different segments of the Korean population, and in what ways their understanding of the world and themselves changed as a result of these interactions. Focusing on the intimate and everyday zones of contact in family and school life, this study more broadly offers a way to understand colonialism without reducing complex local interactions to abstract mechanisms of capital and bureaucratic rule. N WHAT WAYS CAN we talk about colonialism without reducing complex local Ihuman interactions to relations of power, dominance, and hegemony? In pro- posing emotion (see Reddy 2001; Haiyan Lee 2007) or “sensibility” (Wickberg 2007) as a lens through which to investigate the past, a number of studies have implicitly posed a new challenge for scholars of empire. Paying attention to senti- ment and sensibility, they suggest, gets us beyond an analytical grid of race, gender, and class that has dominated cultural history—where colonial studies have reigned and thrived—and allows us to probe more subtle and sensory layers of experience (Wickberg 2007, 673–74). -

Vii. Teaching Staff 2009-2010

113 FCC Curriculum Teaching Staff 114 VII. TEACHING STAFF 2009-2010 Mari Boyd Professor, Literature B.A., Japan Women’s University M.A., Mount Holyoke College Ph.D., University of Hawaii Emmanuel Chéron Professor, Business D.E.S.C.A.F. Ecole Supérieure de Commerce M.B.A., Queen’s University Ph.D., Laval University Richard A. Gardner Professor, Religion B.A., Miami University M.A., Ohio State University M.A., Ph.D., University of Chicago Linda Grove Professor, History B.S., Northwestern University M.A., Ph.D., University of California, Berkeley Michio Hayashi Professor, Art History B.A., University of Tokyo M.A., Ph.D., Columbia University Bruce Hird Professor, English B.A., M.A., University of Hawaii Noriko Hirota Professor, Japanese and Linguistics B.A., Wells College M.A., University of Washington 115 Teaching Staff Teaching Staff 116 Hiromitsu Kobayashi David L. Wank Professor, Art History Professor, Sociology B.A., Meiji University B.A., Oberlin College M.A., Ph.D., University of California, Berkeley M.A., Ph.D., Harvard University Mark R. Mullins Rolf-Harald Wippich Professor, Religion Professor, History B.A., University of Alabama First Staatsexamen M.A., Regent College Dr.Phil., University of Cologne Ph.D., McMaster University Angela Yiu Kate Wildman Nakai Professor, Literature Professor, History B.A., Cornell University B.A., M.A., Stanford University M.A., Ph.D., Yale University Ph.D., Harvard University Michio Yonekura Yoshitaka Okada Professor, Art History Professor, International Business B.A., International Christian University B.A., Seattle University M.A., Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music M.S., Ph.D., University of Wisconsin-Madison Tadashi Anno Valerie Ozaki Associate Professor, Political Science Professor, Mathematics and Statistics B.A., University of Tokyo B.Sc., University of Leeds M.A., Ph.D., University of California, Berkeley M.Sc., Ph.D., University of Manchester James C. -

Hitotsubashi University All Rights Reserved

GNAM | Global Network for Advanced Management GNW | Global Network Week Tokyo Program | March 11-15, 2019 INNOVATION X GLOBALIZATION | JAPAN STYLE Program Outline November 22, 2018 ©2018 Graduate School of International Corporate Strategy Hitotsubashi University All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS The School P3 The Program P9 Maps and Directions P15 Course Platform, Assignments, Details P21 Appendix Hotel Information p29 Contact Information p31 2 AN INTRODUCTION TO HITOTSUBASHI ICS 3 WEB: HITOTSUBASHI UNIVERSITY http://www.hit-u.ac.jp/eng/ Founded in 1875 The first and only university in Japan specializing exclusively in the social sciences Located in Kunitachi City (a suburb of Tokyo) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TMAXYVbKHhc ©2018 Hitotsubashi University Business School, School of International Corporate Strategy. All Rights Reserved. 4 WEB: HITOTSUBASHI ICS http://www.ics.hub.hit-u.ac.jp/ Founded in 2000 Japan’s first national university business school, providing a 100%-English, full-time MBA program The only member of the GNAM* network from Japan, Hitotsubashi ICS offers an intensive program for MBA students visiting from member WEB: businesshttp://www.ibs.ics.hit schools-u.ac.jp/ around the world. Since its launch by GNAM, Hitotsubashi ICS Global Network Week programs has been consistently the second most popular program after Yale. Located in central Tokyo, at Hitotsubashi, the university’s original site. *GNAM (Global Network for Advanced Management ) member schools ©2018 Hitotsubashi University Business School, School of International Corporate Strategy. All Rights Reserved. 5 HITOTSUBASHI ICS | Our Mission, Vision and Values MISSION Achieving “The Best of Two Worlds” by acting as a bridge linking Japan to Asia and the globe, and as an international center of excellence for the creation, management and dissemination of knowledge. -

A Student Study Abroad Survival Guide University of Rhode Island Japanese International Engineering Program

A Student Study Abroad Survival Guide University of Rhode Island Japanese International Engineering Program Table of Contents Pre-Departure Preparation……………………………………………………………2-6 Academic Year …………………………………………………………………. 2 Course Requirements………………………………………………………….. 2 Timeline for Preparing for your Year Abroad ……………………………… 2 Scholarships ………………………………………………………………….... 2 Additional Japanese Language Study Opportunities………..……………… 3 Visa Process……………………………………………….…………………….3 Summer ………………………………………………………………………...4 Travel……………….………………………………………………….. 4 Packing ………………………………………………………………… 5 Banking and Money ………………………………………………….. 6 Year Abroad …………………………………………………………………………... 7 Things to do upon arrival …………………………………………………….. 7 Leaving the Airport ………………………………………………….. 7 Establish Residency …………………………………………………… 8 Housing............………………………………………………………… 8 Communication and Cell Phones ……………………………………. 8 Banking ………………………………………………………………... 8 Orientation …………………………………………………………………….. 9 Life in Tokyo ………………………………………………………………….. 9 Transportation ……………………………………………………….. 10 Groceries ……………………………………………………………… 10 Nightlife ………………………………………………………………. 11 Day Trips ……………………………………………………………… 11 Cultural Integration ………………………………………………… 11 Health and Safety Tips…………………………………………... …………...12 Academics ……………………………………………………………………... 12 Internships ...…………………………………………………………………... 13 After Returning ……………………………………………………………………….. 14 Sharing Your Experiences! …………………………………………………... 14 Pre-departure Preparation This Survival Guide has been developed and maintained by students -

Application Package for MEXT-PGP Scholarship Asian Public Policy

Application Package For MEXT-PGP Scholarship Asian Public Policy Program for Master in Public Policy (Public Economics) Academic Year 2018/19 School of International and Public Policy Hitotsubashi University 2018 Master’s Program Asian Public Policy Program School of International and Public Policy Hitotsubashi University The MEXT-PGP 2018/19 Program Application and Admissions Procedures IMPORTANT NOTICE: The procedure described herein applies to applications under the MEXT-PGP Scholarship. Those applicants applying under the ADB-JSP Scholarship, or are applying independently or under other schemes should use the respective application packages. This program is conducted in English at the Chiyoda campus at National Center of Sciences (Hitotsubashi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo) 1. The Program For the academic year 2018/19, the Asian Public Policy Program (APPP) offers up to three Japanese Government International Priority Graduate Program Scholarship (MEXT-PGP) positions to qualified applicants. The scholarship covers tuition and settlement/resettlement air fare, and provides a monthly stipend for the duration of the two-year Master’s course. The terms and benefits of the scholarship are comparable to those provided under the Japanese Government MEXT Scholarship for Research Students. (Please refer to the relevant webpage of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Sciences and Technology of Japan (MEXT) for details.) 2. Qualifications The qualifications for the scholarship are the same as those for the APPP itself shown below. However, the MEXT-PGP places emphasis on attracting young officials from central banks, financial supervisory agencies, economics related ministries (Finance, Planning, etc.) and policy research institutions from middle- and high-income Asian countries with strong economic and policy ties with Japan, including but not restricted to Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines and Thailand, as well as Korea and Singapore, who have strong academic background and research interest. -

SGH Summary Report 2014-2015

SGH Summary Report 2014-2015 Saitama Prefectural Urawa High School Saitama Prefectural Urawa High School Designated Year 2014 SGH Summary Report (2014 - 2015) Printed: March, 2016 Editor: the Research and Development committee of SGH at Urawa High School Cooperation: Scott Aikin, Kai Osawa Publisher: Saitama Prefectural Urawa High School Principal: Takeshi Sugiyama Address: Ryoke 5 - 3 - 3, Urawa-ku, Saitama City, Saitama, 330 - 9330, Japan Tel: 048 (886) 3000 Fax: 048 (885) 4647 Preface Urawa Prefectural High School was designated as a Super Global High school in 2014. In this report, we have put together a record of activities from the past two years. We applied for SGH for the following reasons. First, we aim to equip Urawa High School students to become global leaders. Students should always try to overcome the difficulties they face. With this in mind I want our students, who are expected to play an important role in the world, to strengthen themselves by nurturing more global views and interacting with various kinds of people. Second, we want to share our approach to education with the world. There are 56 high schools designated as SGHs in Japan, and we want to share our approach with these other schools. Also, the designation as an SGH has increased the number of visitors to our school. I believe transmitting the approach of our school’s all-around education to others will have a positive effect on the future direction of education in Japan. Third, I think being an SGH will augment the education of our school. If you already think that your education is satisfactory, there is little room for improvement. -

Curriculum Vitae

HIROMU NAGAHARA Massachusetts Institute of Technology, History Faculty 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Building E51-255, Cambridge, MA 02139 [email protected], 617-324-4977 EDUCATION Harvard University Ph.D. in History, 2011 Gordon College B.A., with Honors, 2003 EMPLOYMENT Massachusetts Institute of Technology Associate Professor of History 2015-present Assistant Professor of History 2011-2015 Gordon College Adjunct Professor, Department of History 2010-2011 PUBLICATIONS Book Tokyo Boogie-Woogie: Japan’s Pop Era and Its Discontents (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, April 2017). Chapters in Books “Shopan to ryūkōka: ongaku hyōronka sonobe saburō no katsudō ni miru kindai nihon ongaku bunka no chiseigaku” [Chopin and popular songs: the geopolitics of modern Japanese musical culture as seen in the activities of the music critic Sonobe Saburō], in in Tōya Mamoru, et al., Popyurā ongaku saikō: gurōbaru kara rōkaru aidentitī e [Reconsidering popular music: from global to local identities] (Tokyo: Serika Shobō, 2020) 41-73. “Senzen nihon no ongaku bunka ni miru hierarukī to demokurashī” [Hierarchy and democracy in prewar Japan’s musical culture], in Tōya Mamoru, et al., Nihon bunka ni nani wo miru? Popyurā karuchā to no taiwa [What does one see in Japanese culture? Dialogue with popular culture] (Tokyo: Kyōwakoku Press, 2016) pp. 110-134. “Tokyo kōshinkyoku to ankūru na nihon no saihakken” [“Tokyo March” and the Rediscovery of an Uncool Japan], in Tōya Mamoru, ed., Popyurā ongaku kara miru nihon bunka [Examining Japanese Culture from the Perspective of Popular Music] (Tokyo: Serika Shobō, 2014) pp. 182- 206. “The censor as critic: Ogawa Chikagorō and popular music censorship in imperial Japan,” in Rachael Hutchinson, ed., Negotiating Censorship in Modern Japan (Routledge, 2013) 58-73. -

Application Package

Application Package Asian Public Policy Program for Master in Public Policy (Public Economics) Academic Year 2019/20 School of International and Public Policy Hitotsubashi University 2019 Master’s Program Asian Public Policy Program (APPP) School of International and Public Policy Hitotsubashi University The 2019/20 Program Application and Admissions Procedures This program is conducted in English, primarily at the Chiyoda campus located inside the National Center of Sciences building (Hitotsubashi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo). 1. The Program For the academic year 2019/20, the program offers a total of 15 positions to qualified applicants, primarily Asian students. 2. Qualifications Those who have or will have a minimum of two years’ full-time working experience as of March 31, 2019, preferably in economic or other public policy areas of government or central banks, and who hold a Bachelor’s degree or its equivalent that meets any one of the following qualifications: (1) Those who have graduated from universities or colleges which are stipulated in Article 83 of the School Education Law of Japan. (2) Those who have received a Bachelor’s degree under Article 104 of the School Education Law of Japan. (3) Those who have completed at least 16 years of education with a Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) or Bachelor of Science (B.Sc.) degree from accredited universities or colleges in countries other than Japan. (4) Those who are residing in Japan and those who have completed at least 16 years of education by taking courses offered by accredited universities or colleges outside of Japan through correspondence. (5) Those who have completed at least 16 years of education outside of Japan and university’s course in educational institutions accredited by the country authorities. -

Hitotsubashi University

R1-3 Captains of Industry Captains of Industry are the true Fighters, henceforth recognisable as the only true ones: Fighters against Chaos, Necessity and the Devils and Jӧtuns; and lead on Mankind in that great, and alone true, and universal warfare _ Thomas Carlyle, Past and Present, 1843 3 HU at a Glance (As of 2019) (since 1902) Inbound Outbound 6332 (as of 2019) (as of 2018) 1920 1949 Students 92501 14.5% 12.3% 45.0% the Tokyo Hitotsubashi Alumni International Students joining Students joining long 1875 University of University students long-term study or short term study Founded as the Commercial Commerce Active members of Training School the Josuikai Alumni on campus abroad programs abroad programs Association:Around 35,000 4 6 3 Undergraduates Graduate Campuses Schools 4380 Undergraduate Over 2 million 308 7.7 62.7% Number of books Full-time s/t ratio classes 1952 academic staff at seminars /w < 20 students Graduate 130 150 Student exchange Academic exchange 918 agreements agreements International 4 5 Community Distinctive Features of HU During the course of its long history, HU has developed into a leading research university in Japan specializing in the social sciences. In Japan and around the world, HU has demonstrated its particular strength in academic research that makes practical contributions to improving society. For example, HU has been a leader in research on systemic reforms in public policy, the economy, and law, as well as in business management innovation. HU places equal importance on basic and applied research, aiming to establish a suitable theoretical foundation that leads to effective problem resolution. -

GPGS Students by Region

Eric Hurlburt (M.A. & Ph.D in Global Studies Area) I graduated from the GPGS Master's program in 2016 and tunity to pursue research that was from the Doctorate program in 2020. I chose Sophia and the closely tailored to my academic inter- GPGS for several reasons. There are of course several small ests. I wrote my M.A. thesis on the perks: the campus is conveniently located in central Tokyo American occupation of Japan and the (which allowed me easy access to resources such as the propaganda produced during that National Diet Library), the facilities are up-to-date, excellent period. I wrote my Ph.D. dissertation on library, etc. But the reason I first became interested in Sophia American wartime propaganda in the was my desire to have a western style curriculum while study- 20th century. Both topics are interdisci- ing in Japan. Classes in the GPGS are organized and taught plinary in nature and the GPGS not much like their counterparts in western universities and being only provided several avenues to approach these topics but from the United States, it is the type of learning environment I also allowed me to benefit from the varied expertise of the am used to. The class sizes are small which allows for much professors who were of tremendous help in each step of writing more interaction with the professors which greatly helps when process. Additionally, the GPGS staff were key in navigating the tackling more difficult texts or concepts. submission processes and university deadlines. The program faculty was another reason that I chose the My time with Sophia and the GPGS was one of both GPGS program. -

Price Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price Follow Us on Twitter

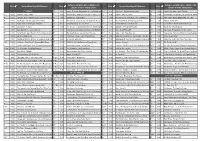

Follow us on twitter @PiccadillyRecs for Follow us on twitter @PiccadillyRecs for Price ✓ Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price ✓ Price ✓ Record Store Day 2019 Releases Price ✓ updates on items selling out etc. updates on items selling out etc. 7" SINGLES 7" 14.99 Queen : Bohemian Rhapsody/I'm In Love With My Car 12" 22.99 John Grant : Remixes Are Also Magic 12" 9.99 Lonnie Liston Smith : Space Princess 7" 12.99 Anderson .Paak : Bubblin' 7" 13.99 Sharon Ridley : Where Did You Learn To Make Love The 12" Way You 11.99Do Hipnotic : Are You Lonely? 12" 10.99 Soul Mekanik : Go Upstairs/Echo Beach (feat. Isabelle Antena) 7" 16.99 Azymuth : Demos 1973-75: Castelo (Version 1)/Juntos Mais 7" Uma Vez9.99 Saint Etienne : Saturday Boy 12" 9.99 Honeyblood : The Third Degree/She's A Nightmare 12" 11.99 Spirit : Spirit - Original Mix/Zaf & Phil Asher Edit 7" 10.99 Bad Religion : My Sanity/Chaos From Within 7" 12.99 Shit Girlfriend : Dress Like Cher/Socks On The Beach 12" 13.99 Hot 8 Brass Band : Working Together E.P. 12" 9.99 Stalawa : In East Africa 7" 9.99 Erykah Badu & Jame Poyser : Tempted 7" 10.99 Smiles/Astronauts, etc : Just A Star 12" 9.99 Freddie Hubbard : Little Sunflower 12" 10.99 Joe Strummer : The Rockfield Studio Tracks 7" 6.99 Julien Baker : Red Door 7" 15.99 The Specials : 10 Commandments/You're Wondering Now 12" 15.99 iDKHOW : 1981 Extended Play EP 12" 19.99 Suicide : Dream Baby Dream 7" 6.99 Bang Bang Romeo : Cemetry/Creep 7" 10.99 Vivian Stanshall & Gargantuan Chums (John Entwistle & Keith12" Moon)14.99 : SuspicionIdles : Meat EP/Meta EP 10" 13.99 Supergrass : Pumping On Your Stereo/Mary 7" 12.99 Darrell Banks : Open The Door To Your Heart (Vocal & Instrumental) 7" 8.99 The Straight Arrows : Another Day In The City 10" 15.99 Japan : Life In Tokyo/Quiet Life 12" 17.99 Swervedriver : Reflections/Think I'm Gonna Feel Better 7" 8.99 Big Stick : Drag Racing 7" 10.99 Tindersticks : Willow (Feat. -

Cultural History of Postwar Japan: Shunsuke Tsurumi Beyond Computopia: Tessa Morris-Suzuki Constructs for Understanding Japan: Yoshio Sugimoto and Ross E

A CULTURAL HISTORY OF POSTWAR JAR\N 1945-1980 Japanese Studies General Editor: Yoshio Sugimoto Images of Japanese Society: Ross E. Mouer and Yoshio Sugimoto An Intellectual History of Wartime Japan: Shunsuke Tsurumi A Cultural History of Postwar Japan: Shunsuke Tsurumi Beyond Computopia: Tessa Morris-Suzuki Constructs for Understanding Japan: Yoshio Sugimoto and Ross E. Mouer Japanese Models of Conflict Resolution: S. N. Eisenstadt and Eyal Ben-Ari The Rise of the Japanese Corporate System: Koji Matsumoto Changing Japanese Suburbia: Eyal Ben-Ari Science, Technology and Society in Postwar Japan: Shigeru Nakayama Group Psychology of the Japanese in Wartime: Toshio Iritani Enterprise Unionism in Japan: Hirosuke Kawanishi Social Psychology of Modern Japan: Munesuke Mita The Origin of Ethnography in Japan: Minoru Kawada Social Stratification in Contemporary Japan: Kenji Kosaka A CULTURAL HISTORY OF POSTWAR JAPAN 1945-1980 Shunsuke Tsurumi ROUTLEDG Routledge E Taylor & Francis Group LONDON AND NEW YORK First published in Japanese in 1984 by Iwanami Shoten, Tokyo This edition published in 1987, reprinted 1990, 1994 by Kegan Paul International Limited This edition first published in 2009 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX 14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © This translation kegan Paul International Limited 1987 Transferred to Digital Printing 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.