Some Australian Literary Myths from the Boer War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bruce Beresford's Breaker Morant Re-Viewed

FILMHISTORIA Online Vol. 30, núm. 1 (2020) · ISSN: 2014-668X The Boers and the Breaker: Bruce Beresford’s Breaker Morant Re-Viewed ROBERT J. CARDULLO University of Michigan Abstract This essay is a re-viewing of Breaker Morant in the contexts of New Australian Cinema, the Boer War, Australian Federation, the genre of the military courtroom drama, and the directing career of Bruce Beresford. The author argues that the film is no simple platitudinous melodrama about military injustice—as it is still widely regarded by many—but instead a sterling dramatization of one of the most controversial episodes in Australian colonial history. The author argues, further, that Breaker Morant is also a sterling instance of “telescoping,” in which the film’s action, set in the past, is intended as a comment upon the world of the present—the present in this case being that of a twentieth-century guerrilla war known as the Vietnam “conflict.” Keywords: Breaker Morant; Bruce Beresford; New Australian Cinema; Boer War; Australian Federation; military courtroom drama. Resumen Este ensayo es una revisión del film Consejo de guerra (Breaker Morant, 1980) desde perspectivas como la del Nuevo Cine Australiano, la guerra de los boers, la Federación Australiana, el género del drama en una corte marcial y la trayectoria del realizador Bruce Beresford. El autor argumenta que la película no es un simple melodrama sobre la injusticia militar, como todavía es ampliamente considerado por muchos, sino una dramatización excelente de uno de los episodios más controvertidos en la historia colonial australiana. El director afirma, además, que Breaker Morant es también una excelente instancia de "telescopio", en el que la acción de la película, ambientada en el pasado, pretende ser una referencia al mundo del presente, en este caso es el de una guerra de guerrillas del siglo XX conocida como el "conflicto" de Vietnam. -

A Study Guide by Robert Lewis

© ATOM 2014 A STUDY GUIDE BY ROBERT LEWIS http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-450-9 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au OVERVIEW In 1902 two Australian soldiers were CURRICULUM arrested for killing prisoners, held in APPLICABILITY prison, allowed access to a lawyer to but his trial and hasty execution was Breaker Morant: The Retrial prepare their defence only one day a cover up for commanding officers is a resource that be used by before the trial started, denied access who issued orders to take no prison- middle and upper secondary to a key witness during the trial, found ers which they later denied. The high students in guilty, and sentenced to death. They command was imposing a program were executed one day after they were of murder and near genocide in a History: told they had been found guilty. campaign to subjugate the local Boer - The development of population in South Africa all for the Australian national identity Could this be a fair trial? purpose of controlling the newly dis- - Federation and the Early covered goldfields. Commonwealth Should an injustice be righted even - Australia and the Boer War after more than 100 years? This was the first war to be filmed by Legal Studies: the newly invented movie camera and - Law and Justice The two soldiers who were treated this the international telegraph meant that way were Lt Harry ‘Breaker’ Morant for the first time events across the Film Studies: and Lt Peter Handcock. world could be on the front page the - Documentary Film next day. The film Breaker Morant The Retrial (Gregory Miller And Nick Bleszynski, In this film fully dramatised scenes 2013, 2 x 52 minute episodes) expos- illustrate the complex story. -

The British Concentration Camp Policy During the Anglo-Boer War

Barbaric methods in the Anglo-Boer War Using Barbaric Methods in South Africa: The British Concentration Camp Policy during the Anglo-Boer War James Robbins Jewell. The Boer War, which is frequently referred to as Britain's Vietnam or Afghanistan, was marked by gross miscalculations on the part of both British military and political leaders. In their efforts to subdue the Boers, Britain used more troops, spent more money, and buried more soldiers than anytime between the Napoleonic wars and World War I - a century during which it had been busy expanding its empire. Despite the miscalculations, lapses in judgement, and blatant stupidity demonstrated throughout the war by the British leaders, historically speaking, one policy remains far more notorious than any other. Unable to bring the war to a conclusion through traditional fighting, the British military, and in particular the two men who were in command, Frederick, Baron Roberts and Herbert, Baron Kitchener, responded to the Boer use of guerilla warfare by instituting a scorched earth combined with a concentration camp policy.! Nearly forty years later, Lord Kitchener's decision to institute a full-scale concentration camp strategy came back to haunt the British. On the eve of the Second World War, when a British ambassador to Gernlany protested Nazi camps, Herman Goering rebuffed the criticism by pulling out an encyclopedia and looking up the entry for concentration camps, which credited the British with being the first to use them in the Boer War.2 Under the scrutiny that comes with the passage of time, the concentration camp policy has rightfully been viewed as not only inhumane, but hopelessly flawed. -

Games and Amusements of Australian Aboriginal Peoples As Outlined in the ‘Papers of Daisy Bates’: Principally Dealing with the South West Region of Western Australia

+ Games and Amusements of Australian Aboriginal peoples as outlined in the ‘Papers of Daisy Bates’: principally dealing with the south west region of Western Australia. Daisy M. Bates Ken Edwards (compiler and transcriber) CISER Ken Edwards is an Associate Professor in Sport, Health and Physical Education at USQ . Ken has compiled and transcribed the information by Daisy M. Bates presented in this publication. [email protected] Games and Amusements of Australian Aboriginal peoples as outlined in the ‘Papers of Daisy Bates’: principally dealing with the south west region of Western Australia. Bates, Daisy May Compiled and transcribed by Associate Professor Ken Edwards of the University of Southern Queensland (USQ). [email protected] Released through the College for Indigenous Studies, Education and Research (CISER) at USQ and with the support and approval of Professor Tracey Bunda. Produced with approval of the copyright holder for the writings of Daisy Bates (with the exception of the book, ‘The Passing of the Aborigines’): The University of Adelaide, Adelaide. The Bates authorised typescripts and other papers have been digitised by the Barr Smith Library, The University of Adelaide https://digital.library.adelaide.edu.au/dspace/handle/2440/69252 2017 For biographical information on Daisy May Bates (1863-1951) refer to the Australian Dictionary of Biography (online): http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/bates-daisy-may-83 Citation details for ADB entry: R. V. S. Wright, 'Bates, Daisy May (1863–1951)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/bates-daisy-may-83/text8643, published first in hardcopy 1979, accessed online. -

Download This PDF File

Illustrating Mobility: Networks of Visual Print Culture and the Periodical Contexts of Modern Australian Writing VICTORIA KUTTAINEN James Cook University The history of periodical illustration offers a rich example of the dynamic web of exchange in which local and globally distributed agents operated in partnership and competition. These relationships form the sort of print network Paul Eggert has characterised as being shaped by everyday exigencies and ‘practical workaday’ strategies to secure readerships and markets (19). In focussing on the history of periodical illustration in Australia, this essay seeks to show the operation of these localised and international links with reference to four case studies from the early twentieth century, to argue that illustrations offer significant but overlooked contexts for understanding the production and consumption of Australian texts.1 The illustration of works published in Australia occurred within a busy print culture that connected local readers to modern innovations and technology through transnational networks of literary and artistic mobility in the years also defined by the rise of cultural nationalism. The nationalist Bulletin (1880–1984) benefited from a newly restricted copyright scene, while also relying on imported technology and overseas talent. Despite attempts to extend the illustrated material of the Bulletin, the Lone Hand (1907–1921) could not keep pace with technologically superior productions arriving from overseas. The most graphically impressive modern Australian magazines, the Home (1920–1942) and the BP Magazine (1928–1942), invested significant energy and capital into placing illustrated Australian stories alongside commercial material and travel content in ways that complicate our understanding of the interwar period. One of the workaday practicalities of the global book trade which most influenced local Australian producers and consumers prior to the twentieth century was the lack of protection for international copyright. -

RECONNAISSANCE Autumn 2021 Final

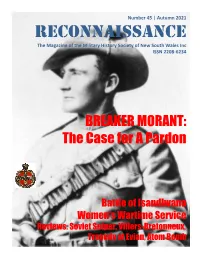

Number 45 | Autumn 2021 RECONNAISSANCE The Magazine of the Military History Society of New South Wales Inc ISSN 2208-6234 BREAKER MORANT: The Case for A Pardon Battle of Isandlwana Women’s Wartime Service Reviews: Soviet Sniper, Villers-Bretonneux, Tragedy at Evian, Atom Bomb RECONNAISSANCE | AUTUMN 2021 RECONNAISSANCE Contents ISSN 2208-6234 Number 45 | Autumn 2021 Page The Magazine of the Military History Society of NSW Incorporated President’s Message 1 Number 45 | Autumn 2021 (June 2021) Notice of Next Lecture 3 PATRON: Major General the Honourable Military History Calendar 4 Justice Paul Brereton AM RFD PRESIDENT: Robert Muscat From the Editor 6 VICE PRESIDENT: Seumas Tan COVER FEATURE Breaker Morant: The Case for a Pardon 7 TREASURER: Robert Muscat By James Unkles COUNCIL MEMBERS: Danesh Bamji, RETROSPECTIVE Frances Cairns 16 The Battle of Isandlwana PUBLIC OFFICER/EDITOR: John Muscat By Steve Hart Cover image: Breaker Morant IN FOCUS Women’s Wartime Service Part 1: Military Address: PO Box 929, Rozelle NSW 2039 26 Service By Dr JK Haken Telephone: 0419 698 783 Email: [email protected] BOOK REVIEWS Yulia Zhukova’s Girl With A Sniper Rifle, review 28 Website: militaryhistorynsw.com.au by Joe Poprzeczny Peter Edgar’s Counter Attack: Villers- 31 Blog: militaryhistorysocietynsw.blogspot.com Bretonneux, review by John Muscat Facebook: fb.me/MHSNSW Tony Matthews’ Tragedy at Evian, review by 37 David Martin Twitter: https://twitter.com/MHS_NSW Tom Lewis’ Atomic Salvation, review by Mark 38 Moore. Trove: https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-532012013 © All material appearing in Reconnaissance is copyright. President’s Message Vice President, Danesh Bamji and Frances Cairns on their election as Council Members and John Dear Members, Muscat on his election as Public Officer. -

An Infantry Officer in Court – a Review of Major James Francis Thomas As Defending Officer for Lieutenants Breaker Morant, Pe

An Infantry Officer In Court – A Review of Major James Francis Thomas as Defending Officer for Lieutenants Breaker Morant, Peter Handcock and George Witton – Boer War Commander James Unkles, RANR Introduction Four men from Australia who joined the Boer war were to be connected by destiny in events that still intrigue historians to this day. Harry ‘Breaker’ Morant, Peter Handcock, George Ramsdale Witton and James Francis Thomas were to meet in circumstances that saw Morant and Handcock executed and Witton sentenced to life imprisonment following military Courts Martial in 1902. This article attempts to review the experiences of Major Thomas, a mounted infantry officer from Tenterfield who joined British Forces as a volunteer and ended up defending six officers, including Breaker Morant on charges of shooting Boer prisoners History of the Boer Wars 1880 - 1902 The Boer War commenced on 11 October 1899, and was fought in three distinct phases. During the first phase the Boers were in the ascendancy. In their initial offensive moves, 20,000 Boers swept into British Natal and encircled the strategic rail junction at Ladysmith. In the following weeks, Boer troops besieged the townships of Mafeking and Kimberley. Phase 1 reached its climax in what has become known as ‘Black Week’ – 10 to15 December 1899. In this one week, three British armies, each seeking to relieve the besieged townships, suffered massive and humiliating defeats in the battles of Stormberg, Magersfontein and Colenso. These defeats shook the British Empire. In response, Britain despatched two regular divisions and replaced the ill-starred General Sir Redvers Buller, with the Empire’s most eminent soldier, Field Marshall Lord Roberts VC, as its commander in South Africa. -

Useful Knowledge 35 Spring 2014

The Magazine of the Mechanics’ Institutes Of Victoria Inc. UsefulNo. Knowledge35 – Spring 2014 PO Box 1080, Windsor VIC 3181 Australia ISSN 1835-5242 Reg No. A0038156G ABN 60 337 355 989 Price: Five Dollars $5 "LEST WE FORGET" There would hardly be a Hall in Victoria or its Some of those who returned formed Soldier adjoining Reserve, or a nearby cenotaph that Settlements, or laboured at community projects, the words ‘Lest we Forget’ are not recorded. like the Great Ocean Road. The phrase is from Rudyard Kipling’s The A hundred years on this is an opportunity for Recessional penned for Queen Victoria’s your Hall, your community to… ‘remember them’. Diamond Jubilee in 1897. This Anzac Day why ‘Lest we forget – Lest we not also remember ‘the forget’ is repeated after going down of the sun’ an entreaty that we will with a lowering of the first four verses as on far off battlefields of Jesus Christ. kick on to a ‘welcome notThose forget threethe sacrifice iconic home’the flag. dance It couldto all localthen words ‘Lest we forget’ service personnel. A are often added at the conclusion of Laurence of Will Longstaff’s Menin Gate at midnight by Will Longstaff Binyon’s famousreflection painting at midnight ‘Menin For the Fallen. Photo from: Collection Database of the Australian ‘They shall not grow old, Gate at Midnight’ when War Memorial under the ID Number: ART09807 as we that are left grow those ghostly legions old/ Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn./ At the going of white crosses or any resting place, with the down of the sun and in the morning,/ We will sounding of The Reveillerise and aagain Roll Call from of district fields remember them. -

Highways Byways

Highways AND Byways THE ORIGIN OF TOWNSVILLE STREET NAMES Compiled by John Mathew Townsville Library Service 1995 Revised edition 2008 Acknowledgements Australian War Memorial John Oxley Library Queensland Archives Lands Department James Cook University Library Family History Library Townsville City Council, Planning and Development Services Front Cover Photograph Queensland 1897. Flinders Street Townsville Local History Collection, Citilibraries Townsville Copyright Townsville Library Service 2008 ISBN 0 9578987 54 Page 2 Introduction How many visitors to our City have seen a street sign bearing their family name and wondered who the street was named after? How many students have come to the Library seeking the origin of their street or suburb name? We at the Townsville Library Service were not always able to find the answers and so the idea for Highways and Byways was born. Mr. John Mathew, local historian, retired Town Planner and long time Library supporter, was pressed into service to carry out the research. Since 1988 he has been steadily following leads, discarding red herrings and confirming how our streets got their names. Some remain a mystery and we would love to hear from anyone who has information to share. Where did your street get its name? Originally streets were named by the Council to honour a public figure. As the City grew, street names were and are proposed by developers, checked for duplication and approved by Department of Planning and Development Services. Many suburbs have a theme. For example the City and North Ward areas celebrate famous explorers. The streets of Hyde Park and part of Gulliver are named after London streets and English cities and counties. -

The Influence of the Friendly Society Movement in Victoria 1835–1920

The Influence of the Friendly Society Movement in Victoria 1835–1920 Roland S. Wettenhall Post Grad. Dip. Arts A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 24 June 2019 Faculty of Arts School of Historical and Philosophical Studies The University of Melbourne ABSTRACT Entrepreneurial individuals who migrated seeking adventure, wealth and opportunity initially stimulated friendly societies in Victoria. As seen through the development of friendly societies in Victoria, this thesis examines the migration of an English nineteenth-century culture of self-help. Friendly societies may be described as mutually operated, community-based, benefit societies that encouraged financial prudence and social conviviality within the umbrella of recognised institutions that lent social respectability to their members. The benefits initially obtained were sickness benefit payments, funeral benefits and ultimately medical benefits – all at a time when no State social security systems existed. Contemporaneously, they were social institutions wherein members attended regular meetings for social interaction and the friendship of like-minded individuals. Members were highly visible in community activities from the smallest bush community picnics to attendances at Royal visits. Membership provided a social caché and well as financial peace of mind, both important features of nineteenth-century Victorian society. This is the first scholarly work on the friendly society movement in Victoria, a significant location for the establishment of such societies in Australia. The thesis reveals for the first time that members came from all strata of occupations, from labourers to High Court Judges – a finding that challenges conventional wisdom about the class composition of friendly societies. -

Daisy Bates in the Digital World

This item is Chapter 8 of Language, land & song: Studies in honour of Luise Hercus Editors: Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch & Jane Simpson ISBN 978-0-728-60406-3 http://www.elpublishing.org/book/language-land-and-song Daisy Bates in the digital world Nick Thieberger Cite this item: Nick Thieberger (2016). Daisy Bates in the digital world. In Language, land & song: Studies in honour of Luise Hercus, edited by Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch & Jane Simpson. London: EL Publishing. pp. 102-114 Link to this item: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/2008 __________________________________________________ This electronic version first published: March 2017 © 2016 Nick Thieberger ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing Open access, peer-reviewed electronic and print journals, multimedia, and monographs on documentation and support of endangered languages, including theory and practice of language documentation, language description, sociolinguistics, language policy, and language revitalisation. For more EL Publishing items, see http://www.elpublishing.org 8 Daisy Bates in the digital world Nick Thieberger School of Languages and Linguistics, University of Melbourne 1. Introduction1 I am pleased to offer this paper in tribute to Luise Hercus who has always been quick to adopt new approaches to working with older sources on Australia’s Indigenous languages (see also Nathan, this volume). In that spirit, I offer an example of using a novel method of working with a large set of material created by Daisy Bates (1859-1951) in the early 1900s. The masses of papers she produced over her lifetime have been an ongoing source of information for Aboriginal people and for researchers (e.g. White 1985; McGregor 2012; Bindon & Chadwick 1992). -

Proof Cover Sheet

PROOF COVER SHEET Author(s): MAX QUANCHI Article Title: Norman H. Hardy: Book Illustrator and Artist Article No: CJPH906298 Enclosures: 1) Query sheet 2) Article proofs Dear Author, 1. Please check these proofs carefully. It is the responsibility of the corresponding author to check these and approve or amend them. A second proof is not normally provided. Taylor & Francis cannot be held responsible for uncorrected errors, even if introduced during the production process. Once your corrections have been added to the article, it will be considered ready for publication. Please limit changes at this stage to the correction of errors. You should not make trivial changes, improve prose style, add new material, or delete existing material at this stage. You may be charged if your corrections are excessive (we would not expect corrections to exceed 30 changes). For detailed guidance on how to check your proofs, please paste this address into a new browser window: http://journalauthors.tandf.co.uk/production/checkingproofs.asp Your PDF proof file has been enabled so that you can comment on the proof directly using Adobe Acrobat. If you wish to do this, please save the file to your hard disk first. For further information on marking corrections using Acrobat, please paste this address into a new browser window: http:// journalauthors.tandf.co.uk/production/acrobat.asp 2. Please review the table of contributors below and confirm that the first and last names are structured correctly and that the authors are listed in the correct order of contribution. This check is to ensure that your name will appear correctly online and when the article is indexed.