Patents and Industrialization: an Historical Overview of the British Case, 1624-1907

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East-West Dialogues : Economic Historians, the Cold War, and Détente

Original citation: Berg, Maxine. (2015) East-West dialogues : economic historians, the Cold War, and Détente. The Journal of Modern History, 87 (1). pp. 36-71. Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/70955 Copyright and reuse: The Warwick Research Archive Portal (WRAP) makes this work by researchers of the University of Warwick available open access under the following conditions. Copyright © and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in WRAP has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. Publisher’s statement: © 2015 by Maxine Berg http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/680261 A note on versions: The version presented in WRAP is the published version or, version of record, and may be cited as it appears here. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications East-West Dialogues: Economic Historians, the Cold War, and Détente* Maxine Berg University of Warwick In the late 1950s a new international historical association was conceived, the International Economic History Association. From 1960 it organized a succession of major congresses that brought together historians from across Europe, the Soviet Union, and North America, along with smaller numbers from Japan, Australia and New Zealand, and “Third World” countries. -

Slave Traders and Planters in the Expanding South: Entrepreneurial Strategies, Business Networks, and Western Migration in the Atlantic World, 1787-1859

SLAVE TRADERS AND PLANTERS IN THE EXPANDING SOUTH: ENTREPRENEURIAL STRATEGIES, BUSINESS NETWORKS, AND WESTERN MIGRATION IN THE ATLANTIC WORLD, 1787-1859 Tomoko Yagyu A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2006 Approved by Advisor: Peter A. Coclanis Reader: William L. Barney Reader: Paul W. Rhode Reader: W. Fitzhugh Brundage Reader: Lisa Lindsay © 2006 Tomoko Yagyu ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Tomoko Yagyu: Slave Traders and Planters in the Expanding South: Entrepreneurial Strategies, Business Networks, and Western Migration in the Atlantic World, 1787-1859 (Under the direction of Peter A. Coclanis) This study attempts to analyze the economic effects of the domestic slave trade and the slave traders on the American South in a broader Atlantic context. In so doing, it interprets the trade as a sophisticated business and traders as speculative, entrepreneurial businessmen. The majority of southern planters were involved in the slave trade and relied on it to balance their financial security. They evaluated their slaves in cash terms, and made strategic decisions regarding buying and selling their property to enhance the overall productivity of their plantations in the long run. Slave traders acquired business skills in the same manner as did merchants in other trades, utilizing new forms of financial options in order to maximize their profit and taking advantage of the market revolution in transportation and communication methods in the same ways that contemporary northern entrepreneurs did. They were capable of making rational moves according to the signals of global commodity markets and financial movements. -

Gunn-Vernon Cover Sheet Escholarship.Indd

UC Berkeley GAIA Books Title The Peculiarities of Liberal Modernity in Imperial Britain Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6wj6r222 Journal GAIA Books, 21 ISBN 9780984590957 Authors Gunn, Simon Vernon, James Publication Date 2011-03-15 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Peculiarities of Liberal Modernity in Imperial Britain Edited by Simon Gunn and James Vernon Published in association with the University of California Press “A remarkable achievement. This ambitious and challenging collection of tightly interwoven essays will find an eager au- dience among students and faculty in British and imperial history, as well as those interested in liberalism and moder- nity in other parts of the world.” Jordanna BaILkIn, author of The Culture of Property: The Crisis of Liberalism in Modern Britain “This volume investigates no less than the relationship of liberalism to Britain’s rise as an empire and the first modern nation. In its global scope and with its broad historical perspective, it makes a strong case for why British history still matters. It will be central for anyone interested in understanding how modernity came about.” Frank TrenTMann, author of Free Trade Nation: Consumption, Commerce, and Civil Society in Modern Britain In this wide-ranging volume, leading scholars across several disciplines—history, literature, sociology, and cultural studies—investigate the nature of liberalism and modernity in imperial Britain since the eighteenth century. They show how Britain’s liberal version of modernity (of capitalism, democracy, and imperialism) was the product of a peculiar set of historical cir- cumstances that continues to haunt our neoliberal present. -

British Business History," I Was Simultaneously Pleased, Flattered, and Highly Apprehensive

BritishBusiness History: A PersonalSurvey Peter L. Payne California Instltutc of Technology When Professor Freudenberger kindly invited me to address this conference on the subject of "the methods, goals, and areas of research of British business history," I was simultaneously pleased, flattered, and highly apprehensive. Indeed, the more I thought about it, the more conscious I became of my own inade- quacy to present such a survey. It is true that I have a reason- able idea of what is going on in this field; a knowledge of the subjects recently and currently under investigation, of the method being employed in those inquiries, and of the objectives being pursued; but this information is only partial and I am somewhat removed, both at the University of Aberdeen and at Caltech, from the center of the ferment to be fully confident of the validity of the generalizations that spring to mind. For these reasons may I request your indulgence and present you with a personal, if not somewhat idiosyncratic, view of the British scene. Gallons of ink have been spilt in the learned journals, in prefaces to symposiums, and introductions to monographs in efforts to define business history and I do not propose to add to the flood. Nevertheless, it has to be said that in Great Britain, business history -- despite substantial developments in recent years -- is still regarded as an integral part of economic his- tory. As Peter Mathias recently explained to a conference on business history held at Cranfield Institute of Technology: When we are talking about business history, seeking to explain and justify our activities, the target for such reflections tends to be the academic con•nunity of other historians and the justifications are sought primarily in terms of academic values within historiography. -

HIS Volume 35 Issue 1 Cover and Front Matter

THE HISTORICAL1 TOURNAI! VOLUME 35, i MARCH 1992 26-MAR-1992 BLDSC BPlJSNTi5ft HISTORICflL JQURNflL -LONDON- CAMBRIDGE UN IVERSITY PRESS- US 16.360000 CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.126, on 30 Sep 2021 at 03:38:41, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X00025565 EDITORS J. S. MORRILL. PH.D. J. STEINBERG, PHD EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Cambridge members C. M.ANDREW, PHD PROFESSOR D. E. D. BEALES, LJTT.D., F.B.A. I. C. W. BLANMNG. PH.D., F.B.A. PROFESSOR W. O. CHADWICK, O.M., K.B.E., D.D., F.B.A. PROFESSOR P. F. CLARKE, LJTT.D., F.B.A. PROFESSOR SIR GEOFFREY ELTON, LJTT.D., F.B.A. PROFESSOR D. K. FIELDHOUSE, LITT.D. V. A C GATRELL, PHD. PROFESSOR SIR HARRY HINSLEY, M.A., F.B.A. H. M. PELL ING, LITT.D. PROFESSOR GV R. D SKINNER, M.A., F.B.A. American members PROFESSOR J. GUY (University of Rochester) PROFESSOR H.JAMES (Princeton University) THE HISTORICAL JOURNAL (ISSN 0018-246X) is published quarterly in March, June, September and December. Four parts form a volume. The subscription price of volume 35, 1992 (which includes postage' is £82.00 (US $159.00 in the USA and Canada) for institutions, £46 (US $6g in the USA and Canada) for individuals ordering direct from the Press and certifying (hat the journal is tor their personal use. Single parts cost £22.00 net (US $40.00 in the USA and Canada 1 plus postage. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/146545 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2017-12-05 and may be subject to change. Nijmeegse Geografische Cahiers nr. 40 Small Business Growth in Contrasting Environments Peter Vaessen Department of Economie Geography Faculty of Administrative Sciences/KU Nijmegen small business growth in contrasting environments CIP-GEGEVENS KONINKLIJKE BIBLIOTHEEK, DEN HAAG Vaessen, Peter Mathias Maria. Small Business Growth in Contrasting Environments / P.M M Vaessen. - Nijmegen: Depart ment of Social Geography, Faculty of Administrative Sciences, Catholic University of Nijmegen. - 111, fig., tab. - (Nijmeegse geografische cahiers ; no 40) Also pubi, in commercial ed : Utrecht : Royal Dutch Geographic Society ; Nijmegen : Faculty of Administrative Sciences, Catholic University of Nijmegen, 1993. - Netherlands geographical studies, ISSN 0169-1839; 165). Thesis Nijmegen. - With rcf. ISBN 90-70898-38-1 Subject headings: small business gTowth. ISBN 90-70898-38-1 (Nijmeegse geografische cahiers 40) ISBN 90-6809-178-6 (Netherlands geographical studies 165) Copyright © 1993 Catholic University of Nijmegen, The Netherlands Alle rechten voorbehouden. Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden vermenigvuldigd en/of openbaar gemaakt door middel van druk, fotokopie of op welke andere wijze dan ook zonder voorafgaande toestemming van de -

Nicholas FR Crafts Born March 9, 1949, Nottingham, England

1 Curriculum Vitae: Nicholas F. R. Crafts Born March 9, 1949, Nottingham, England; married with 3 children. Educated Trinity College, Cambridge. First Class Honours, Economics Tripos, parts I & II, 1967-1970. Employment 1971-72: Lecturer in Economic History, University of Exeter. 1972-77: Lecturer in Economics, University of Warwick (on leave 1974-6). 1974-76: Visiting Assistant Professor of Economics, University of California, Berkeley. 1977-86: CUF Lecturer in Economics, University of Oxford and Fellow in Economics, University College, Oxford (on leave 1982-3). 1982-83: Visiting Professor of Economics, Stanford University. 1987-88: Professor of Economic History, University of Leeds. 1988-95: Professor of Economic History, University of Warwick. 1995-2005: Professor of Economic History, London School of Economics. 2006-09: Professor of Economic History, University of Warwick. 2010-19: Professor of Economic History and Director of ESRC CAGE Research Centre, University of Warwick. 2019-: Professor of Economic History, University of Sussex (0.3FTE) Honours Wrenbury Scholarship for Best Degree in Economics at Cambridge in 1970. Fellow of the British Academy, 1992. Honorary Professor, University of Warwick, 1995-2005. Founding Academician, Academy of Learned Societies for the Social Sciences, 1999. Tjalling C. Koopmans Asset Award, Tilburg University, 2012. CBE, Queen’s Birthday Honours List, 2014. 2 Fellow of the Cliometric Society, 2015. Jonathan Hughes Prize for Excellence in Teaching Economic History, Economic History Association, 2017. Emeritus Professor, University of Warwick, 2019- Doctor Honoris Causa, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, 2020. Major Grants 1992-3: 279,000 Ecus from European Commission to direct Research Network on Postwar Economic Growth, with G. -

The Early Modern Atlantic Economy

The Early Modern Atlantic Economy Edited by John J. McCusker and Kenneth Morgan published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011– 4211, USA www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarco´n 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain © Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in Plantin 10/12pt [vn] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data The early modern Atlantic economy/edited by John J. McCusker and Kenneth Morgan. p. cm. ISBN 0 521 78249 X 1. Great Britain – colonies – commerce – history – 18th century. 2. Great Britain – commerce – America – history – 18th century. 3. America – commerce – Great Britain – history – 18th century. 4. France – colonies – commerce – history – 17th century. 5. France – commerce – America – history – 17th century. 6. America – commerce – France – history – 17th century. I. McCusker, John J. II. Morgan, Kenneth. HF3093.E2 2000 382'.09182'1–dc21 00–028924 ISBN 0521 78249X hardback Contents List of -

Peter Mathias

Peter Mathias 10 January 1928 – 1 March 2016 elected Fellow of the British Academy 1977 by MAXINE BERG Fellow of the Academy Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the British Academy, XVII, 35–50 Posted 27 September 2018. © British Academy 2018 PETER MATHIAS at All Souls College, Oxford, July 1984 Peter Mathias was Chichele Professor of Economic History at the University of Oxford, the leading chair in economic history, during the period of the subject’s greatest strength, from the 1960s to the 1980s. Economic history later went in different direc- tions; some would say that it declined, at least for a time. In his reflections on this later period, Mathias said that economic history lost the battle, but won the war. It had become a central part of mainstream historical research and teaching. If it did so this was in no small part due to Mathias’s activities. Richard Smith called him the most internationally oriented of economic historians, and indeed he was fundamental to a major internationalisation of the subject in the third quarter of the twentieth century. His contribution was intellectual, through his focus on comparative industrialisation, and institutional, through his considerable success in building networks that crossed disciplines, countries and barriers of class and culture. He was always open to, and in touch with, new intellectual developments in economic history; he had a quick sense of where the opportunities opened for the field and of the way in which his subject fitted into the wider historical disciplines. He worked on many international and national committees, demonstrating great integrity, courage and fairness.1 Peter Mathias was an economic historian of industry, business and technology. -

UCD CENTRE for ECONOMIC RESEARCH WORKING PAPER SERIES 2014 Did Science Cause the Industrial Revolution? Cormac Ó Gráda, Univer

UCD CENTRE FOR ECONOMIC RESEARCH WORKING PAPER SERIES 2014 Did Science Cause the Industrial Revolution? Cormac Ó Gráda, University College Dublin WP14/14 October 2014 UCD SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS UNIVERSITY COLLEGE DUBLIN BELFIELD DUBLIN 4 Did Science Cause the Industrial Revolution?1 Cormac Ó Gráda University College Dublin and CAGE, University of Warwick ABSTRACT: This paper reviews debates about the role of science and technology before and during the British Industrial Revolution. Keywords: economic history, science, human capital JEL classification: N13, O10, O30 1 Review of Margaret C. Jacob, The First Knowledge Economy: Human Capital and the European Economy, 1750-1850. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. The comments of John Kanefsky, Morgan Kelly, Liam Kennedy, Deirdre McCloskey, Joel Mokyr, Peter Solar, and Eric Vanhaute are gratefully acknowledged. The standard disclaimer applies. Did Science Cause the Industrial Revolution? ‘We are not anxious about the honour of acquiring gold medals nor of making an eclat in philosophical societies.’ Matthew Boulton to James Watt, 17832 Margaret Jacob believes that economists and economic historians have got some key elements of the British Industrial Revolution wrong. In The First Knowledge Economy (FKE) she pleads with them to focus more on James Watt’s improved steam engine and less on Richard Arkwright’s water frame (the water-powered device that revolutionized cotton-spinning); more on the complexities of science-based technological change and less on its determinants and quantitative impact. She wants to lure them away from their stubborn belief that ‘skilled artisans, who seldom cracked a book, held the key to British industrial prowess’ (p. 85)3. -

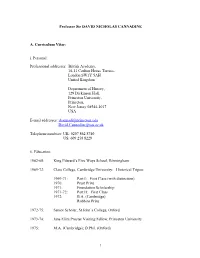

David Nicholas Cannadine

Professor Sir DAVID NICHOLAS CANNADINE A. Curriculum Vitae: i. Personal: Professional addresses: British Academy, 10-11 Carlton House Terrace, London SW1Y 5AH United Kingdom Department of History, 129 Dickinson Hall, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey 08544-1017 USA E-mail addresses: [email protected] [email protected] Telephone numbers: UK: 0207 862 8740 US: 609 258 8228 ii. Education: 1962-68: King Edward’s Five Ways School, Birmingham 1969-72: Clare College, Cambridge University: Historical Tripos: 1969-71: Part I: First Class (with distinction) 1970: Prust Prize 1971: Foundation Scholarship 1971-72: Part II: First Class 1972: B.A. (Cambridge) Robbins Prize 1972-75: Senior Scholar, St John’s College, Oxford 1973-74: Jane Eliza Procter Visiting Fellow, Princeton University 1975: M.A. (Cambridge); D.Phil. (Oxford) 1 iii. Appointments: 1975-77: Research Fellow, St John’s College, Cambridge 1976-80: Assistant Lecturer in History, Cambridge University 1977-88: Fellow and College Lecturer in History, Christ’s College, Cambridge: 1977-83: Director of Studies in History 1979-81: Tutor 1979-88: Member of the College Council 1981-88: Fellows’ Steward 1980-88 Lecturer in History, Cambridge University 1983-85: Member, Faculty Board of History 1988-92: Professor of History, Columbia University 1989-90: Member, University Senate 1991-92: Chairman, Department Personnel Committee 1992-98: Governing Body, Society of Fellows 1992-98: Moore Collegiate Professor of History, Columbia University 1993: Acting Department Chairman (Fall Term) 1998-2003: Director of the Institute of Historical Research, and Professor of History, School of Advanced Study, University of London 1999-2004: Member, University of London Honorary Degrees Committee 2003-08: Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother Professor of British History, Institute of Historical Research, School of Advanced Study, University of London 2008-11: Whitney J. -

Queens' College the Record 2018-19

Queens’ College The Record 2018-19 The Record Queens’ College The Record 2018-19 (including Easter term 2018) Queens’ College The Record 2018-19 (including Easter term 2018) The Record is a formal account of the year at Queens’ College. The 2018-19 edition can now be read on the College website. If old members would like to receive a hard copy of The Record, please inform the Alumni & Development Office by sending your name, address and matriculation year, along with a £5 cheque (made payable to ‘Queens’ College, Cambridge’) to help cover production and postage costs. Thank you. 2 QUEENS’ COLLEGE THE RECORD 2019 3 THE FELLOWSHIP (AUGUST 2019) Visitor: The Rt Hon. Beverley McLachlin, P.C., Chief Justice of Canada Graham Swift, M.A., Litt D.h.c. (East Anglia and London), D.Univ.h.c. (York), F.R.S.L. Stephen Fry, M.A., D.Litt. h.c. (East Anglia), D.Univ.h.c. (Anglia Ruskin Univ.and Sussex). Patroness: Her Majesty The Queen Awn Shawkat Al-Khasawneh, M.A., LL.M., Istiqlal Order (First Class), Kawkab Order (First Class), Nahda Order (First Class), Jordan; Grand Officier, Légion d’Honneur, France. President Paul Greengrass, M.A. Film Director & Producer. The Rt Hon. Professor Lord Eatwell, of Stratton St Margaret, M.A., Ph.D. (Harvard). Emeritus Edward Cullinan, C.B.E., B.A., A.A.Dip., Hon F.R.I.A.S., F.R.S.A., R.A., R.I.B.A. Professor of Financial Policy. Michael Gibson, M.B.E., M.A. Mohamed El-Erian, M.A., D.Phil.