Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barbara Nissman Pianist

THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Barbara Nissman Pianist THURSDAY EVENING, FEBRUARY 1, 1979, AT 8:30 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Fantasy in C major, Op. 17 SCHUMANN Durchaus fantastisch und leidenschaftlich vorzutragen Massig. Durchaus energisch Langsam getragen. Durchaus leise zu haJten Sonata No.1, Op. 1 PROKOFIEV INTERMISSION Fantasy, Op. 49 CHOPIN Transcendental Etude No.9, "Ricordanza" LISZT Rbapsodie Espagnole LISZT Tonight's recital is a centennial year "bonus" for Debut and Encore Series subscribers, generously underwritten by The Power Foundation. Centennial Season - Forty-sixth Concert Debut and Encore Series "Bonus" Concert About the Artist Barbara Nissman's career began on this campus where she arrived as the recipient of a four-year scholarship. She continued to win awards while in college, culminating with the Stanley Medal, the School of Music's highest honor. After receiving her bachelor, master, and doctoral degrees at The University of Michigan, studying with pianist Gyorgy Sandor, Miss Nissman made her Ann Arbor professional debut at the 1971 May Festival as the "Alumni Night" featured soloist . with the Philadelphia Orchestra. Subsequently, Eugene Ormandy invited her to perform with them again the following season, and from this beginning grew her successes in the United States. Miss Nissman enjoys success on both sides of the Atlantic. In America, her consistent repeat engagements with Stanislaw Skrowaczewski and the Minnesota Orchestra, Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops, and Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra attest to her artistry. She has worked with Italian conductor Riccardo Muti and tours regularly with orchestras throughout England, Holland, Germany, and Scandinavia. -

Season 2019-2020

23 Season 2019-2020 Thursday, September 19, at 7:30 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, September 20, at 2:00 Saturday, September 21, Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor at 8:00 Sunday, September 22, Hélène Grimaud Piano at 2:00 Coleman Umoja, Anthem for Unity, for orchestra World premiere—Philadelphia Orchestra commission Bartók Piano Concerto No. 3 I. Allegretto II. Adagio religioso—Poco più mosso—Tempo I— III. Allegro vivace—Presto—Tempo I Intermission Dvořák Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95 (“From the New World”) I. Adagio—Allegro molto II. Largo III. Scherzo: Molto vivace IV. Allegro con fuoco—Meno mosso e maestoso— Un poco meno mosso—Allegro con fuoco This program runs approximately 1 hour, 45 minutes. LiveNote® 2.0, the Orchestra’s interactive concert guide for mobile devices, will be enabled for these performances. These concerts are sponsored by Leslie A. Miller and Richard B. Worley. These concerts are part of The Philadelphia Orchestra’s WomenNOW celebration. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 24 ® Getting Started with LiveNote 2.0 » Please silence your phone ringer. » Make sure you are connected to the internet via a Wi-Fi or cellular connection. » Download the Philadelphia Orchestra app from the Apple App Store or Google Play Store. » Once downloaded open the Philadelphia Orchestra app. » Tap “OPEN” on the Philadelphia Orchestra concert you are attending. » Tap the “LIVE” red circle. -

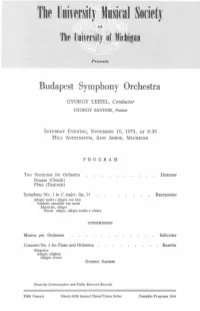

The Universitj Musical Societj of the University of Michigan

The UniversitJ Musical SocietJ of The University of Michigan Presents Budapest Symphony Orchestra GYORGY LEHEL, Conductor GYORGY SANDOR, Pianist SATURDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 10, 1973, AT 8:30 HILL AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Two Nocturnes for Orchestra DEBUSSY Nuages (Clouds) Fetes (Festivals) Symphony No.1 in C major, Op. 21 BEETHOVEN Adagio mol to; allegro con brio Andante cantabile con moto Menuetto, allegro Finale: adagio, allegro moIto e vivace INTERMISSION Musica per Orchestra SZOLLOSY Concerto No.3 for Piano and Orchestra • BARTOK Allegretto Adagio religioso Allegro vivace GYORGY SANDOR Deutsche Grammophon and Pathe Marconi Records. Fifth Concert Ninety-fifth Annual Choral Union Series Complete Programs 3848 PROGRAM NOTES Two Nocturnes-Nuages (Clouds) and Fetes (Festivals) CLAUDE ACHILLE DEBUSSY Though Debussy was openly averse to written explanations of his music, and though the score contains no program, he did write this description of the Nocturnes: "The title Nocturnes is to be interpreted here in a general and, more particularly, in a decorative sense. Therefore, it is not meant to designate the usual form of the Nocturne, but rather all the various impressions and the special effects of light that the word suggests. NlIa.ges renders the im mutable aspect of the sky and the slow, solemn motion of the clouds, fading into the poignant gray softly touched with white. Fetes gives us the vibrating, dancing rhythm of the atmosphere with sudden flash es of light. There is also the episode of the procession (a dazzling fantastic vision) which passes through the festive scene and becomes merged in it. But the background remains persistently the same: the festival with its blending of music and luminous dust participating in the cosmic rhythm." -PAUL AFFELDER Symphony No.1 in C major, Op. -

Eugene Ormandy Commercial Sound Recordings Ms

Eugene Ormandy commercial sound recordings Ms. Coll. 410 Last updated on October 31, 2018. University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts 2018 October 31 Eugene Ormandy commercial sound recordings Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 5 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 7 - Page 2 - Eugene Ormandy commercial sound recordings Summary Information Repository University of Pennsylvania: Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts Creator Ormandy, Eugene, 1899-1985 -

Bartók Béla Életének Krónikája Translated by Márta Rubin

BÉLA BARTÓK JNR. Chronicles of Béla Bartók’s Life BÉLA BARTÓK JNR. CHRONICLES OF BÉLA BARTÓK’S LIFE Magyarságkutató Intézet Budapest, 2021 Translation based on Béla Bartók Jnr.’s original Bartók Béla életének krónikája Translated by Márta Rubin Book Editor: Gábor Vásárhelyi Assistant: Ágnes Virághalmy The publication of this book was sponsored by EMMI. A kötet megjelenését az EMMI támogatta. Original edition © Béla Bartók Jnr., 1981 Revised edition © Béla Bartók Jnr.’s legal successor (Gábor Vásárhelyi), 2021 Translation © Márta Rubin, 2021 ISBN 978-615-6117-26-7 CONTENTS Foreword ......................................................7 Preface .......................................................11 Family, Infancy (1855–1889) ....................................15 School Years (1890–1903) .......................................21 Connecting to the Music Life of Europe (1904–1906) ...............71 Settling In Budapest. Systematic Collection of Folk Songs (1907–1913) ................99 War Years (1914–1919) ........................................149 After World War I (1920–1921) .................................189 Great Concert Tours on Two Continents (1922–1931) .............205 Economic Crisis (1932–1933) ..................................335 At The Academy of Sciences. Great Compositions (1934–1938) .....359 World War II. Second and Third American Tour (1939–1945) .......435 Last Journey Home, “… But For Good” (1988) ....................507 Identification List of Place Names ...............................517 FOREWORD FOREWORD I have the honour of being a family member of Béla Bartók Jnr., the author of this book. He was the husband of my paternal aunt and my Godfather. Of our yearly summer vacations spent together, I remember well that summer when one and a half rooms of the two-room-living-room cottage were occupied by the scraps of paper big and small, letters, notes, railway tickets, and other documents necessary for the compilation of this book. -

Exhibition Catalogues 66

P ERCY G RAINGER: FROM MEAT-SHUN-MENT TO CUT-CURE-CRAFT Curated By Alessandro Servadei A display celebrating the 7th International Music Medicine Symposium held at the University of Melbourne’s Faculty of Music from 12-15 July, 1998 GRAINGER MUSEUM THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE 1998 P ERCY G RAINGER: FROM MEAT-SHUN-MENT TO CUT-CURE-CRAFT Curated By Alessandro Servadei G rainger Museum Music / Medicine Special Exhibition: July 1998 — Page 2 One reads that the Polynesians are so healthy that they need no doctors, because they never get ill. As a matter of fact I never get ill – never incapacitated. I only feel wretched. But that, I think, is soul-sickness: I have too many worries. But if I had fewer I would accomplish less for my race. Victory is the only thing I care about. Excerpt from Percy Grainger, letter to Cyril Scott, 13 September 1947. CREDITS: Catalogue researched, compiled and written by Alessandro Servadei, Assistant Curator. Desktop publishing, design and layout by Alessandro Servadei. Digital imaging by Alessandro Servadei and the Design & Print Centre, The University of Melbourne. Printing by the Design & Print Centre. Museum assistance by Geoff Down, Acting Curator, Jenny Hayman and Fiona Moore. Accession number refers to Grainger Collection, Grainger Museum in The University of Melbourne. Art works: size in cm. height preceding width. Idiosyncrasies of spelling and punctuation in quotations reflect Grainger’s own usage. “Legends” refer to written information about museum artefacts which have been supplied by Percy Grainger. COVER: Percy Grainger hiking in 1923 (location unknown). SPECIAL NOTE: Meat-shun-ment = vegetarianism and cut-cure-craft = surgery in Grainger’s Nordic or ‘blue-eyed’ English. -

November 17, 2013 Concert Program Booklet

North Shore Choral Society With David Schrader, Organist Rejoice!November 17, 2013 Glenview Community Church Glenview, Illinois North Shore Choral Society Julia Davids, Music Director PROGRAM God Is Gone Up ................................................................................................ Gerald Finzi Paean ........................................................................................................Kenneth Leighton David Schrader, organist Rejoice in the Lord Alway .............................................................................. Henry Purcell Elizabeth Jankowski, alto; Alan Taylor, tenor; Michael Orlinsky, bass Ave Verum Corpus ......................................................................................... William Byrd Ave Verum Corpus ......................................................................................... Edward Elgar Hail, Gladdening Light ..................................................................................Charles Wood Julia Brueck, conductor The Lord Is My Shepherd .......................................................................... Howard Goodall Rachel Sparrow, soprano Julia Brueck, conductor Let All the World in Every Corner Sing ..................................................Kenneth Leighton — Intermission — I Was Glad ............................................................................Charles Hubert Hastings Parry Rachel Sparrow, soprano; Elizabeth Jankowski, alto; Alan Taylor, tenor; Michael Orlinsky, bass Rejoice in the Lamb ................................................................................. -

Ole Bulls Regneverden 5.-7

Faktaopplysning Ole Bull, til lærer Ole Bulls Regneverden 5.-7. trinn Forslag til forarbeid Bruk ulike læremidler og la elevene bli kjent med Ole Bull. Faktaarket er et hjelpemiddel til deg som lærer. Fakta Ole Bull 1810-1880 Fiolinist fra Bergen Født på Svaneapoteket hvor faren var apoteker. Spilte fiolin fra han var 8 år. Dyktig improvisator Komponerte en del, men kun få verk er bevart. Var visjonær og initiativrik Hadde et liberalt forhold til penger. Følgende tekst er redigert og hentet fra Wikipedia Ole Bull var mye av en improvisator og hadde for en stor del komposisjonene i hodet. Mens han levde, oppnådde han å bli en eventyrfigur. Stjernestatusen sank nok noe i årene etter hans død. Men Ole Bull var mye mer enn komponist og sagnomsust fiolinvirtuos. Han var også en betydelig kulturpersonlighet og inspirator for en selvstendig norsk kunst i vid mening, med stor betydning for kunstmusikk og folke- musikk, for litteratur og teater. Ole Bull hadde store visjoner og ville mye. Han drømte om en norsk ope- ra, og han arbeidet for en høyere utdanningsinstitusjon for musikk. Ole Bull ble født på Svaneapoteket i Bergen, der hans far, Johan Storm Bull, var apoteker. Hans mor var Anna Dorothea (Geelmeyden). Han vokste opp i et musikkinteressert miljø. Ole Bulls første lærere i fiolinspill var konsertmester ved Musikselskabet «Harmonien» (nå Bergen Fil- harmoniske orkester). Ole Bull viste tydelig et usedvanlig talent og skal ha fått sin første skikkelige fiolin i en alder av 8 år. Da han var 18 år gammel ble han sendt til hovedstaden for å ta eksamen artium etter å ha vært elev ved Bergen katedralskole. -

NEWS LETTER Northfield, Minnesota from the NAHA Office to the Association Members

16994 NAHA Summer NL 6/30/05 7:48 AM Page 2 The Norwegian-American Historical Association NEWS LETTER Northfield, Minnesota From the NAHA Office to the Association Members NUMBER 125 EDITOR, KIM HOLLAND SUMMER 2005 by the director of the Norwegian Nobel Institute, Geir NEW BOARD OF DIRECTORS ELECTED Lundestad. The symposium concludes with music, a banquet and remarks by distinguished guests. NAHA’s 27th triennial membership meeting was held Register at: www.stolaf.edu/events/norway2005/confer- on April 30, 2005. We are pleased to announce that four new ence/registration A list of hotels in Northfield is included on members joined the Board of Directors. These individuals the website. We look forward to seeing you for this important bring a geographic diversity and a commitment to sharing their event which will showcase the ongoing close relationship these time and talents for the betterment of the Norwegian-American two countries share. While registering for the conference you Historical Association. can click on “Speakers” and check out the backgrounds on the Joining the NAHA Board for the first time are H.Theodore various speakers. Grindal, a health care attorney from Eden Prairie, Minnesota, Katherine Hanson, a professor in the Department of Scandinavian NORWEGIAN NATIONAL OPERA PERFORMS Studies at the University of Washington, James Honsvall, a CPA PEER GYNT from Stillwater, Minnesota and Mary Rand Taylor, a philanthro- pist from La Jolla, California. Returning members to the NAHA Board include: Mark your calendars! The Norwegian National Opera H. George Anderson, Joan Buckley, Ruth Crane, Karen Davidson, will perform Peer Gynt on Tuesday and Wednesday, October 18 David Hill, Nils Lang-Ree, Zay Lenaburg, Mary Ann Olsen, and 19 at the Ordway Theatre in St. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 103, 1983

Boston Symphony Orchestra SEIJI OZAWA, Music Director - - /BOSTON \ . ,\ SEIJI OZAWA As ,\t Director V .T 103rd Season Mt Musu 1983-84 Savor the sense of Remy Imported by Remy Martin Amerique, Inc., N.Y SINCE !4 VS.O.P COGNAC. ; Sole U.S.A. Distributor, Premiere Wine Merchants Inc., N.Y. 80 Proof. REMY MARTINI Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Sir Colin Davis, Principal Guest Conductor Joseph Silverstein, Assistant Conductor One Hundred and Third Season, 1983-84 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Leo L. Beranek, Chairman Nelson J. Darling, Jr., President Mrs. Harris Fahnestock, Vice-President George H. Kidder, Vice-President Sidney Stoneman, Vice-President Roderick M. MacDougall, Treasurer John Ex Rodgers, Assistant Treasurer Vernon R. Alden Archie C. Epps III Thomas D. Perry, Jr. David B. Arnold, Jr. Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick William J. Poorvu J.R Barger Mrs. John L. Grandin Irving W. Rabb Mrs. John M. Bradley E. James Morton Mrs. George R. Rowland Mrs. Norman L. Cahners David G. Mugar Mrs. George Lee Sargent George H.A. Clowes, Jr. Albert L. Nickerson William A. Selke Mrs. Lewis S. Dabney John Hoyt Stookey Trustees Emeriti Abram T. Collier, Chairman ofthe Board Emeritus Philip K. Allen E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Mrs. James H. Perkins Allen G. Barry Edward M. Kennedy Paul C. Reardon Richard P. Chapman Edward G. Murray John L. Thorndike John T. Noonan Administration of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Thomas W Morris - General Manager William Bernell - Artistic Administrator Daniel R. Gustin - Assistant Manager B.J. Krintzman - Director ofPlanning Anne H. Parsons - Orchestra Manager Caroline Smedvig - Director ofPromotion Charles D. -

Twentieth Century Music for Unaccompanied Trumpet: an Annotated Bibliography. Timothy Wayne Justus Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1995 Twentieth Century Music for Unaccompanied Trumpet: An Annotated Bibliography. Timothy Wayne Justus Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Justus, Timothy Wayne, "Twentieth Century Music for Unaccompanied Trumpet: An Annotated Bibliography." (1995). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6113. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6113 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Faculty F Aculty, Librarians and a W Ard R Ecipients

Faculty 397 ACEVEDO, MIGUEL, Professor of Geography. BSEE, MSEE, University of Texas at Austin; MEng, Faculty PhD, University of California at Berkeley. ACREE, WILLIAM, JR., Professor of Chemistry. All personnel listings in this section are BS, MS, PhD, University of Missouri at Rolla. based on information available when this ADAMS, JENNY, Assistant Professor of English. bulletin went to press. BA, University of California at Los Angeles; MA, PhD, Under the current system for the selection University of Chicago. of graduate faculty (approved October 1992 by ADELMAN, AMIE, Assistant Professor of Visual the Graduate Council), all full-time faculty Arts. BFA, Arizona State University; MFA, University members of the rank of assistant professor, of Kansas. associate professor, and professor are members of the graduate faculty, but individual faculty ADKISON, JUDITH A., Associate Professor of the members may be classified as Category I, II, or Department of Teacher Education and Administration, Associate Dean of the College of III. The qualifications for appointment to a Education. BA, Smith College; MA, PhD, University category depend upon the faculty member’s of New Mexico. record of scholarly, creative and research ac ALBARRAN, ALAN B., Professor and Chair of the tivities. Category III reflects the highest level ecipients of scholarly attainment. Faculty members in Department of Radio, Television and Film. BA, MA, any of the three categories may serve on thesis Marshall University, PhD, Ohio State University. or dissertation committees as a member. Cat ALBERS-MILLER, NANCY D., Associate Professor egory II faculty members may serve as of Marketing and Logistics. BS, University of Texas at d R directors of thesis committees and co-directors Austin; MBA, Southwest Texas State University; PhD, ar of dissertation committees.