Rice University Gyorgy Sandor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

Index Abulfeda crater chain (Moon), 97 Aphrodite Terra (Venus), 142, 143, 144, 145, 146 Acheron Fossae (Mars), 165 Apohele asteroids, 353–354 Achilles asteroids, 351 Apollinaris Patera (Mars), 168 achondrite meteorites, 360 Apollo asteroids, 346, 353, 354, 361, 371 Acidalia Planitia (Mars), 164 Apollo program, 86, 96, 97, 101, 102, 108–109, 110, 361 Adams, John Couch, 298 Apollo 8, 96 Adonis, 371 Apollo 11, 94, 110 Adrastea, 238, 241 Apollo 12, 96, 110 Aegaeon, 263 Apollo 14, 93, 110 Africa, 63, 73, 143 Apollo 15, 100, 103, 104, 110 Akatsuki spacecraft (see Venus Climate Orbiter) Apollo 16, 59, 96, 102, 103, 110 Akna Montes (Venus), 142 Apollo 17, 95, 99, 100, 102, 103, 110 Alabama, 62 Apollodorus crater (Mercury), 127 Alba Patera (Mars), 167 Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP), 110 Aldrin, Edwin (Buzz), 94 Apophis, 354, 355 Alexandria, 69 Appalachian mountains (Earth), 74, 270 Alfvén, Hannes, 35 Aqua, 56 Alfvén waves, 35–36, 43, 49 Arabia Terra (Mars), 177, 191, 200 Algeria, 358 arachnoids (see Venus) ALH 84001, 201, 204–205 Archimedes crater (Moon), 93, 106 Allan Hills, 109, 201 Arctic, 62, 67, 84, 186, 229 Allende meteorite, 359, 360 Arden Corona (Miranda), 291 Allen Telescope Array, 409 Arecibo Observatory, 114, 144, 341, 379, 380, 408, 409 Alpha Regio (Venus), 144, 148, 149 Ares Vallis (Mars), 179, 180, 199 Alphonsus crater (Moon), 99, 102 Argentina, 408 Alps (Moon), 93 Argyre Basin (Mars), 161, 162, 163, 166, 186 Amalthea, 236–237, 238, 239, 241 Ariadaeus Rille (Moon), 100, 102 Amazonis Planitia (Mars), 161 COPYRIGHTED -

2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Annual Report Table of Contents the Michael J

Roadmaps for Progress 2017 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Annual Report Table of Contents The Michael J. Fox Foundation is dedicated to finding a cure for 2 A Note from Michael Parkinson’s disease through an 4 Annual Letter from the CEO and the Co-Founder aggressively funded research agenda 6 Roadmaps for Progress and to ensuring the development of 8 2017 in Photos improved therapies for those living 10 2017 Donor Listing 16 Legacy Circle with Parkinson’s today. 18 Industry Partners 26 Corporate Gifts 32 Tributees 36 Recurring Gifts 39 Team Fox 40 Team Fox Lifetime MVPs 46 The MJFF Signature Series 47 Team Fox in Photos 48 Financial Highlights 54 Credits 55 Boards and Councils Milestone Markers Throughout the book, look for stories of some of the dedicated Michael J. Fox Foundation community members whose generosity and collaboration are moving us forward. 1 The Michael J. Fox Foundation 2017 Annual Report “What matters most isn’t getting diagnosed with Parkinson’s, it’s A Note from what you do next. Michael J. Fox The choices we make after we’re diagnosed Dear Friend, can open doors to One of the great gifts of my life is that I've been in a position to take my experience with Parkinson's and combine it with the perspectives and expertise of others to accelerate possibilities you’d improved treatments and a cure. never imagine.’’ In 2017, thanks to your generosity and fierce belief in our shared mission, we moved closer to this goal than ever before. For helping us put breakthroughs within reach — thank you. -

Charles Darwin: a Companion

CHARLES DARWIN: A COMPANION Charles Darwin aged 59. Reproduction of a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron, original 13 x 10 inches, taken at Dumbola Lodge, Freshwater, Isle of Wight in July 1869. The original print is signed and authenticated by Mrs Cameron and also signed by Darwin. It bears Colnaghi's blind embossed registration. [page 3] CHARLES DARWIN A Companion by R. B. FREEMAN Department of Zoology University College London DAWSON [page 4] First published in 1978 © R. B. Freeman 1978 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publisher: Wm Dawson & Sons Ltd, Cannon House Folkestone, Kent, England Archon Books, The Shoe String Press, Inc 995 Sherman Avenue, Hamden, Connecticut 06514 USA British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Freeman, Richard Broke. Charles Darwin. 1. Darwin, Charles – Dictionaries, indexes, etc. 575′. 0092′4 QH31. D2 ISBN 0–7129–0901–X Archon ISBN 0–208–01739–9 LC 78–40928 Filmset in 11/12 pt Bembo Printed and bound in Great Britain by W & J Mackay Limited, Chatham [page 5] CONTENTS List of Illustrations 6 Introduction 7 Acknowledgements 10 Abbreviations 11 Text 17–309 [page 6] LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Charles Darwin aged 59 Frontispiece From a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron Skeleton Pedigree of Charles Robert Darwin 66 Pedigree to show Charles Robert Darwin's Relationship to his Wife Emma 67 Wedgwood Pedigree of Robert Darwin's Children and Grandchildren 68 Arms and Crest of Robert Waring Darwin 69 Research Notes on Insectivorous Plants 1860 90 Charles Darwin's Full Signature 91 [page 7] INTRODUCTION THIS Companion is about Charles Darwin the man: it is not about evolution by natural selection, nor is it about any other of his theoretical or experimental work. -

Meat: a Novel

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Faculty Publications 2019 Meat: A Novel Sergey Belyaev Boris Pilnyak Ronald D. LeBlanc University of New Hampshire, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/faculty_pubs Recommended Citation Belyaev, Sergey; Pilnyak, Boris; and LeBlanc, Ronald D., "Meat: A Novel" (2019). Faculty Publications. 650. https://scholars.unh.edu/faculty_pubs/650 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sergey Belyaev and Boris Pilnyak Meat: A Novel Translated by Ronald D. LeBlanc Table of Contents Acknowledgments . III Note on Translation & Transliteration . IV Meat: A Novel: Text and Context . V Meat: A Novel: Part I . 1 Meat: A Novel: Part II . 56 Meat: A Novel: Part III . 98 Memorandum from the Authors . 157 II Acknowledgments I wish to thank the several friends and colleagues who provided me with assistance, advice, and support during the course of my work on this translation project, especially those who helped me to identify some of the exotic culinary items that are mentioned in the opening section of Part I. They include Lynn Visson, Darra Goldstein, Joyce Toomre, and Viktor Konstantinovich Lanchikov. Valuable translation help with tricky grammatical constructions and idiomatic expressions was provided by Dwight and Liya Roesch, both while they were in Moscow serving as interpreters for the State Department and since their return stateside. -

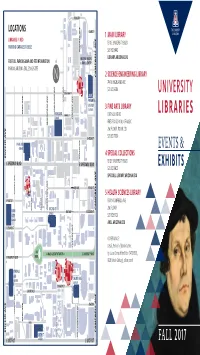

2017 Fall Event Brochure

RING RD LOCATIONS ELM ST 1 MAIN LIBRARY LIBRARIES IN RED 1510 E UNIVERSITY BLVD PARKING GARAGES IN BLUE WARREN AVE WARREN 520.621.6442 ARIZONA HEALTH LIBRARY.ARIZONA.EDU FOR FULL PARKING MAP AND FEE INFORMATION SCIENCES CENTER PARKING.ARIZONA.EDU, 520.626.7275 CAMPBELL AVE CAMPBELL 2 SCIENCE-ENGINEERING LIBRARY 744 N HIGHLAND AVE 520.621.6384 E DRACHMAN ST UAMC VINE AVE PATIENT & VISITOR GARAGE 3 FINE ARTS LIBRARY HIGHLAND AVE PARK AVE PARK HIGHLAND E MABEL ST 1017 N OLIVE RD GARAGE AVE CHERRY FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC MOUNTAIN AVE MOUNTAIN 2nd FLOOR, ROOM 233 E HELEN ST 520.621.7009 PARK AVE GARAGE 4 SPECIAL COLLECTIONS EUCLID AVE WARREN AVE WARREN 1510 E UNIVERSITY BLVD E SPEEDWAY BLVD E SPEEDWAY BLVD 520.621.6423 SPECCOLL.LIBRARY.ARIZONA.EDU ONE WAY E FIRST ST MUSIC TYNDALL AVE TYNDALL BLDG 5 HEALTH SCIENCES LIBRARY E FIRST ST 1501 N CAMPBELL AVE MOUNTAIN AVE MOUNTAIN CAMPBELL AVE CAMPBELL PALM DR PALM OLIVE RD SECOND ST 2nd FLOOR MAIN ONE WAY E SECOND ST GATE GARAGE 520.626.6125 GARAGE AHSL.ARIZONA.EDU E SECOND ST COVER IMAGE: CHERRY AVE CHERRY Detail, Portrait of Martin Luther, OLD MALL CLOSED TO TRAFFIC E UNIVERSITY BLVD by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553), MAIN E UNIVERSITY BLVD 1528 (Veste Coburg), oil on panel TYNDALL AVE GARAGE CHERRY AVE GARAGE E FOURTH ST E FOURTH ST CHERRY AVE CHERRY ENKE DR TYNDALL AVE TYNDALL PARK AVE PARK LOWELL CAMPBELL AVE CAMPBELL EUCLID AVE NAT’L CHAMPIONS DR CHAMPIONS NAT’L SIXTH ST HIGHLAND AVE E SIXTH ST GARAGE E SIXTH ST FALL 2017 SPECIAL COLLECTIONS SPECIAL EVENTS speccoll.library.arizona.edu Library Cats Tech Breakfast Contact: Kathy McCarthy | 520.626.8332 Saturday, October 28, 9–11 a.m., Science-Engineering Library [email protected] All alumni and friends are welcome at our Homecoming EXHIBIT | Opens August 7 celebration. -

Regional Oral History Off Ice University of California the Bancroft Library Berkeley, California

Regional Oral History Off ice University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Richard B. Gump COMPOSER, ARTIST, AND PRESIDENT OF GUMP'S, SAN FRANCISCO An Interview Conducted by Suzanne B. Riess in 1987 Copyright @ 1989 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West,and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between the University of California and Richard B. Gump dated 7 March 1988. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Discovering the Lost Race Story: Writing Science Fiction, Writing Temporality

Discovering the Lost Race Story: Writing Science Fiction, Writing Temporality This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia 2008 Karen Peta Hall Bachelor of Arts (Honours) Discipline of English and Cultural Studies School of Social and Cultural Studies ii Abstract Genres are constituted, implicitly and explicitly, through their construction of the past. Genres continually reconstitute themselves, as authors, producers and, most importantly, readers situate texts in relation to one another; each text implies a reader who will locate the text on a spectrum of previously developed generic characteristics. Though science fiction appears to be a genre concerned with the future, I argue that the persistent presence of lost race stories – where the contemporary world and groups of people thought to exist only in the past intersect – in science fiction demonstrates that the past is crucial in the operation of the genre. By tracing the origins and evolution of the lost race story from late nineteenth-century novels through the early twentieth-century American pulp science fiction magazines to novel-length narratives, and narrative series, at the end of the twentieth century, this thesis shows how the consistent presence, and varied uses, of lost race stories in science fiction complicates previous critical narratives of the history and definitions of science fiction. In examining the implicit and explicit aspects of temporality and genre, this thesis works through close readings of exemplar texts as well as historicist, structural and theoretically informed readings. It focuses particularly on women writers, thus extending previous accounts of women’s participation in science fiction and demonstrating that gender inflects constructions of authority, genre and temporality. -

Barbara Nissman Pianist

THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Barbara Nissman Pianist THURSDAY EVENING, FEBRUARY 1, 1979, AT 8:30 RACKHAM AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Fantasy in C major, Op. 17 SCHUMANN Durchaus fantastisch und leidenschaftlich vorzutragen Massig. Durchaus energisch Langsam getragen. Durchaus leise zu haJten Sonata No.1, Op. 1 PROKOFIEV INTERMISSION Fantasy, Op. 49 CHOPIN Transcendental Etude No.9, "Ricordanza" LISZT Rbapsodie Espagnole LISZT Tonight's recital is a centennial year "bonus" for Debut and Encore Series subscribers, generously underwritten by The Power Foundation. Centennial Season - Forty-sixth Concert Debut and Encore Series "Bonus" Concert About the Artist Barbara Nissman's career began on this campus where she arrived as the recipient of a four-year scholarship. She continued to win awards while in college, culminating with the Stanley Medal, the School of Music's highest honor. After receiving her bachelor, master, and doctoral degrees at The University of Michigan, studying with pianist Gyorgy Sandor, Miss Nissman made her Ann Arbor professional debut at the 1971 May Festival as the "Alumni Night" featured soloist . with the Philadelphia Orchestra. Subsequently, Eugene Ormandy invited her to perform with them again the following season, and from this beginning grew her successes in the United States. Miss Nissman enjoys success on both sides of the Atlantic. In America, her consistent repeat engagements with Stanislaw Skrowaczewski and the Minnesota Orchestra, Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops, and Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra attest to her artistry. She has worked with Italian conductor Riccardo Muti and tours regularly with orchestras throughout England, Holland, Germany, and Scandinavia. -

Sunnyvale Heritage Resources

CARIBBEAN DR 3RD AV G ST C ST BORDEAUX DR H ST 3RD AV Heritage Trees CARIBBEAN DR CASPIAN CT GENEVA DR ENTERPRISE WY 4TH AV Local Landmarks E ST CASPIAN DR BALTIC WY Heritage Resources 5TH AV JAVA DR 5TH AV MOFFETT PARK DR CROSSMAN AV 300-ft Buffer CHESAPEAKE TR GIBRALTAR CT GIBRALTAR DR ORLEANS DR MOFFETT PARK DR 7TH AV MACON RD ANVILWOOD City Boundary ENTERPRISEWY CT G ST C ST MOFFETT PARK CT 8TH AV HUMBOLDT CT PERSIAN DR FORGEWOODAV SR-237 ANVILWOODAV INNSBRUCK DR ELKO DR 9TH AV E ST FAIR OAKS WY BORREGAS AV D ST P O R P O I S ALDERWOODAV 11TH AV MOFFETT PARK DR E BA Y TR PARIA BIRCHWOODDR MATHILDA AV GLIESSEN JAEGALS RD GLIN SR-237 PLAZA DR PLENTYGLIN LA ROCHELLE TR TASMAN DR ENTERPRISE WY ENTERPRISE MONTEGO VIENNA DR KASSEL INNOVATION WAY BRADFORD DR MOLUCCA MONTEREY LEYTE MORSE AV KIHOLO LEMANS ROSS DR MUNICH LUND TASMAN CT KARLSTAD DR ESSEX AV COLTON AV FULTON AV DUNCAN AV HAMLIN CT SAGINAW FAIR OAKS AV TOYAMA DR SACO LAWRENCEEXPRESSWAY GARNER DR LYON US-101 SALERNO SAN JORGEKOSTANZ TIMOR KIEL CT SIRTE SOLOMON SUEZ LAKEBIRD DR CT DRIFTWOOD DRIFTWOOD CT CHARMWOOD CHARMWOOD CT SKYLAKE VALELAKE CT CT CLYDE AV BREEZEWOOD CT LAKECHIME DR JENNA PECOS WY AHWANEE AV LAKEDALE WY WEDDELL LOTUSLAKE CT GREENLAKE DR HIDDENLAKE DR WEDDELL DR MEADOWLAKE DR ALMANOR AV FAIRWOODAV STONYLAKE SR-237 LAKEFAIR DR CT CT LYRELAKE LYRELAKE HEM BLAZINGWOOD DR REDROCK CT LO CT CK ALTURAS AV SILVERLAKEDR AV CT CANDLEWOOD LAKEHAVEN DR BURNTWOOD CT C B LAKEHAVEN A TR U JADELAKE SAN ALESO AV R N MADRONE AV LAKEKNOLL DR N D T L PALOMAR AV SANTA CHRISTINA W CT -

The Creative Process

The Creative Process THE SEARCH FOR AN AUDIO-VISUAL LANGUAGE AND STRUCTURE SECOND EDITION by John Howard Lawson Preface by Jay Leyda dol HILL AND WANG • NEW YORK www.johnhowardlawson.com Copyright © 1964, 1967 by John Howard Lawson All rights reserved Library of Congress catalog card number: 67-26852 Manufactured in the United States of America First edition September 1964 Second edition November 1967 www.johnhowardlawson.com To the Association of Film Makers of the U.S.S.R. and all its members, whose proud traditions and present achievements have been an inspiration in the preparation of this book www.johnhowardlawson.com Preface The masters of cinema moved at a leisurely pace, enjoyed giving generalized instruction, and loved to abandon themselves to reminis cence. They made it clear that they possessed certain magical secrets of their profession, but they mentioned them evasively. Now and then they made lofty artistic pronouncements, but they showed a more sincere interest in anecdotes about scenarios that were written on a cuff during a gay supper.... This might well be a description of Hollywood during any period of its cultivated silence on the matter of film-making. Actually, it is Leningrad in 1924, described by Grigori Kozintsev in his memoirs.1 It is so seldom that we are allowed to study the disclosures of a Hollywood film-maker about his medium that I cannot recall the last instance that preceded John Howard Lawson's book. There is no dearth of books about Hollywood, but when did any other book come from there that takes such articulate pride in the art that is-or was-made there? I have never understood exactly why the makers of American films felt it necessary to hide their methods and aims under blankets of coyness and anecdotes, the one as impenetrable as the other. -

Season 2019-2020

23 Season 2019-2020 Thursday, September 19, at 7:30 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, September 20, at 2:00 Saturday, September 21, Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor at 8:00 Sunday, September 22, Hélène Grimaud Piano at 2:00 Coleman Umoja, Anthem for Unity, for orchestra World premiere—Philadelphia Orchestra commission Bartók Piano Concerto No. 3 I. Allegretto II. Adagio religioso—Poco più mosso—Tempo I— III. Allegro vivace—Presto—Tempo I Intermission Dvořák Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95 (“From the New World”) I. Adagio—Allegro molto II. Largo III. Scherzo: Molto vivace IV. Allegro con fuoco—Meno mosso e maestoso— Un poco meno mosso—Allegro con fuoco This program runs approximately 1 hour, 45 minutes. LiveNote® 2.0, the Orchestra’s interactive concert guide for mobile devices, will be enabled for these performances. These concerts are sponsored by Leslie A. Miller and Richard B. Worley. These concerts are part of The Philadelphia Orchestra’s WomenNOW celebration. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 24 ® Getting Started with LiveNote 2.0 » Please silence your phone ringer. » Make sure you are connected to the internet via a Wi-Fi or cellular connection. » Download the Philadelphia Orchestra app from the Apple App Store or Google Play Store. » Once downloaded open the Philadelphia Orchestra app. » Tap “OPEN” on the Philadelphia Orchestra concert you are attending. » Tap the “LIVE” red circle. -

15Th Annual Student Research and Creativity Celebration, SUNY Buffalo State

I II III III I I I I I I I I 15th Annual Student Research and Creativity Celebration, SUNY Buffalo State I II III III I I I I I I I I Editor Jill K. Singer, Ph.D. Director, Office of Undergraduate Research Sponsored by Office of Undergraduate Research Office of Academic Affairs Research Foundation for SUNY/Buffalo State Cover Design and Layout: Carol Alex The following individuals and offices are acknowledged for their many contributions: Sean Fox, Ellofex, Inc. Tom Coates, Events Management, and staff, especially Maryruth Glogowski, Director, E.H. Butler Library, Mary Beth Wojtaszek and the library staff Department and Program Coordinators (identified below) Carole Schaus, Office of Undergraduate Research Kaylene Waite, Computer Graphics Specialist and very special thanks to Carol Alex, Center for Bruce Fox, Photographer Development of Human Services Department and Program Coordinators for the Fifteenth Annual Student Research and Creativity Celebration Lisa Anselmi, Anthropology Bill Lin, Computer Information Systems Kyeonghi Baek, Political Science Dan MacIsaac, Physics Saziye Bayram, Mathematics Candace Masters, Art Education Carol Beckley, Theater Amy McMillan, Biology Lynn Boorady, Fashion and Textile Technology Susan McMillen, Faculty Development Betty Cappella, Higher Education Administration Michaelene Meger, Exceptional Education Louis Colca, Social Work Michael Niman, Communication Michael Cretacci, Criminal Justice Jill Norvilitis, Psychology Carol DeNysschen, Dietetics and Nutrition Kathleen O’Brien, Hospitality and Tourism