Triple Play -- Three Exciting Baseball Adventures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

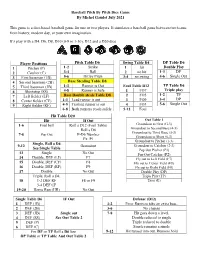

Baseball Pitch by Pitch Dice Game Instruction

Baseball Pitch By Pitch Dice Game By Michel Gaudet July 2021 This game is a dice-based baseball game for one or two players. It simulates a baseball game between two teams from history, modern day, or your own imagination. It’s play with a D4. D6, D8, D10 (0-9 or 1-10), D12 and a D20 dice. Player Positions Pitch Table D6 Swing Table D4 DP Table D6 1 Pitcher (P) 1-2 Strike 1 hit Double Play 2 Catcher (C) 3-4 Ball 2 no hit 1-3 DP 3 First baseman (1B) 5-6 Hit by Pitch 3-4 no swing 4-6 Single Out 4 Second baseman (2B) Base Stealing Table D8 5 Third baseman (3B) 1-3 Runner is Out Foul Table D12 TP Table D6 6 Shortstop (SS) 4-8 Runner is Safe 1 FO7 Triple play 7 Left fielder (LF) Base Double steals Table D8 2 FO5 1-2 TP 8 Center fielder (CF) 1-3 Lead runner is out 3 FO9 3-4 DP 9 Right fielder (RF) 4-5 Trailing runner is out 4 FO3 5-6 Single Out 6-8 Both runners reach safely 5-12 Foul Hit Table D20 Hit If Out Out Table 1 1-6 Foul ball Roll a D12 (Foul Table) Groundout to First (G-3) Roll a D6 Groundout to Second Base (4-3) Groundout to Third Base (5-3) 7-8 Pop Out P-D6 Number Groundout to Short (6-3) Ex. P1 Groundout to Pitcher (1-3) Single, Roll a D6 9-12 Groundout Groundout to Catcher (2-3) See Single Table Pop Out Pitcher (P1) 13 Single No Out Pop Out Catcher (P2) 14 Double, DEF (LF) F7 Fly out to Left Field (F7) 15 Double, DEF (CF) F8 Fly out to Center Field (F8) 16 Double, DEF (RF) F9 Fly out to Right Field (F9) 17 Double No Out Double Play (DP) Triple, Roll a D4, Triple Play (TP) 18 1-2 DEF RF F8 or F9 Error (E) 3-4 DEF CF 19-20 Home Run (HR) No Out Single Table D6 IF Out Defense (D12) 1 DEF (1B) 1-2 Error Runners take an extra base. -

Iscore Baseball | Training

| Follow us Login Baseball Basketball Football Soccer To view a completed Scorebook (2004 ALCS Game 7), click the image to the right. NOTE: You must have a PDF Viewer to view the sample. Play Description Scorebook Box Picture / Details Typical batter making an out. Strike boxes will be white for strike looking, yellow for foul balls, and red for swinging strikes. Typical batter getting a hit and going on to score Ways for Batter to make an out Scorebook Out Type Additional Comments Scorebook Out Type Additional Comments Box Strikeout Count was full, 3rd out of inning Looking Strikeout Count full, swinging strikeout, 2nd out of inning Swinging Fly Out Fly out to left field, 1st out of inning Ground Out Ground out to shortstop, 1-0 count, 2nd out of inning Unassisted Unassisted ground out to first baseman, ending the inning Ground Out Double Play Batter hit into a 1-6-3 double play (DP1-6-3) Batter hit into a triple play. In this case, a line drive to short stop, he stepped on Triple Play bag at second and threw to first. Line Drive Out Line drive out to shortstop (just shows position number). First out of inning. Infield Fly Rule Infield Fly Rule. Second out of inning. Batter tried for a bunt base hit, but was thrown out by catcher to first base (2- Bunt Out 3). Sacrifice fly to center field. One RBI (blue dot), 2nd out of inning. Three foul Sacrifice Fly balls during at bat - really worked for it. Sacrifice Bunt Sacrifice bunt to advance a runner. -

Baseball/Softball

July2006 ?fe Aatuated ScowS& For Basebatt/Softbatt Quick Keys: Batter keywords: Press this: To perform this menu function: Keyword: Situation: Keyword: Situation: a.Lt*s Balancescoresheet IB Single SAC Sacrificebunt ALT+D Show defense 2B Double SF Sacrifice fly eLt*B Edit plays 3B Triple RBI# # Runs batted in RLt*n Savea gamefile to disk HR Home run DP Hit into doubleplay crnl*n Load a gamefile from disk BB Walk GDP Groundedinto doubleplay alr*I Inning-by-inning summary IBB Intentionalwalk TP Hit into triple play nlr*r Lineupcards HP Hit by pitch PB Reachedon passedball crRL*t List substitutions FC Fielder'schoice WP Reachedon wild pitch alr*o Optionswindow CI Catcher interference E# Reachon error by # ALT+N Gamenotes window BI Batter interference BU,GR Bunt, ground-ruledouble nll*p Playswindow E# Reachedon error by DF Droppedfoul ball ALr*g Quit the program F# Flied out to # + Advanced I base alr*n Rosterwindow P# Poppedup to # -r-r Advanced2 bases CTRL+R Rosterwindow (edit profiles) L# Lined out to # +++ Advanced3 bases a,lr*s Statisticswindow FF# Fouledout to # +T Advancedon throw 4 J-l eLt*:t Turn the scoresheetpage tt- tt Groundedout # to # +E Advanced on effor l+1+1+ .ALr*u Updatestat counts trtrft Out with assists A# Assistto # p4 Sendbox score(to remotedisplay) #UA Unassistedputout O:# Setouts to # Ff, Edit defensivelineup K Struck out B:# Set batter to # F6 Pitchingchange KS Struck out swinging R:#,b Placebatter # on baseb r7 Pinchhitter KL Struck out looking t# Infield fly to # p8 Edit offensivelineup r9 Print the currentwindow alr*n1 Displayquick keyslist Runner keywords: nlr*p2 Displaymenu keys list Keyword: Situation: Keyword: Situation: SB Stolenbase + Adv one base Hit locations: PB Adv on passedball ++ Adv two bases WP Adv on wild pitch +++ Adv threebases Ke1+vord: Description: BK Adv on balk +E Adv on error 1..9 PositionsI thru 9 (p thru rf) CS Caughtstealing +E# Adv on error by # P. -

Ba Mss 121 Bl-587.69 – Bl-593.69

Collection Number BA MSS 121 BL-587.69 – BL-593.69 Title Tom Meany Scorebooks Inclusive Dates 1947 – 1963 NY teams Access By appointment during regular hours, email [email protected]. Abstract These scorebooks have scored games from spring training, All-Star games, and World Series games, and a few regular season games. Volume 1 has Jackie Robinson’s first game, April 15, 1947. Biography Tom Meany was recruited to write for the new Brooklyn edition of the New York Journal in 1922. The following year he earned a byline in the Brooklyn Daily Times as he covered the Dodgers. Over the years, Meany's sports writing career saw stops at numerous papers including the New York Telegram (later the World-Telegram), New York Star, Morning Telegraph, as well as magazines such as PM and Collier's. Following his sports writing career, Meany joined the Yankees in 1958. In 1961 he joined the expansion Mets as publicity director and later served as promotions director before his untimely death in 1964 at the age of 60. He received the Spink Award in 1975. Source: www.baseballhall.org Content List Volume 1 BL-587.69 1947 - Spring training, season games April 15, Jackie Robinson’s first game World Series - Dodgers v. Yankees 1948 - Spring training Volume 2 BL-588.69 1948 – Season games World Series, Indians vs. Braves 1962 - World Series, Giants vs. Yankees Volume 3 BL-589.69 1949 -Spring training, season games 1950 - May, Jul 11 All-Star game World Series, Yankees vs. Phillies 1951 - Playoff games, Dodgers vs. Giants World Series, Giants vs. -

Baseball Cyclopedia

' Class J^V gG3 Book . L 3 - CoKyiigtit]^?-LLO ^ CORfRIGHT DEPOSIT. The Baseball Cyclopedia By ERNEST J. LANIGAN Price 75c. PUBLISHED BY THE BASEBALL MAGAZINE COMPANY 70 FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK CITY BALL PLAYER ART POSTERS FREE WITH A 1 YEAR SUBSCRIPTION TO BASEBALL MAGAZINE Handsome Posters in Sepia Brown on Coated Stock P 1% Pp Any 6 Posters with one Yearly Subscription at r KtlL $2.00 (Canada $2.00, Foreign $2.50) if order is sent DiRECT TO OUR OFFICE Group Posters 1921 ''GIANTS," 1921 ''YANKEES" and 1921 PITTSBURGH "PIRATES" 1320 CLEVELAND ''INDIANS'' 1920 BROOKLYN TEAM 1919 CINCINNATI ''REDS" AND "WHITE SOX'' 1917 WHITE SOX—GIANTS 1916 RED SOX—BROOKLYN—PHILLIES 1915 BRAVES-ST. LOUIS (N) CUBS-CINCINNATI—YANKEES- DETROIT—CLEVELAND—ST. LOUIS (A)—CHI. FEDS. INDIVIDUAL POSTERS of the following—25c Each, 6 for 50c, or 12 for $1.00 ALEXANDER CDVELESKIE HERZOG MARANVILLE ROBERTSON SPEAKER BAGBY CRAWFORD HOOPER MARQUARD ROUSH TYLER BAKER DAUBERT HORNSBY MAHY RUCKER VAUGHN BANCROFT DOUGLAS HOYT MAYS RUDOLPH VEACH BARRY DOYLE JAMES McGRAW RUETHER WAGNER BENDER ELLER JENNINGS MgINNIS RUSSILL WAMBSGANSS BURNS EVERS JOHNSON McNALLY RUTH WARD BUSH FABER JONES BOB MEUSEL SCHALK WHEAT CAREY FLETCHER KAUFF "IRISH" MEUSEL SCHAN6 ROSS YOUNG CHANCE FRISCH KELLY MEYERS SCHMIDT CHENEY GARDNER KERR MORAN SCHUPP COBB GOWDY LAJOIE "HY" MYERS SISLER COLLINS GRIMES LEWIS NEHF ELMER SMITH CONNOLLY GROH MACK S. O'NEILL "SHERRY" SMITH COOPER HEILMANN MAILS PLANK SNYDER COUPON BASEBALL MAGAZINE CO., 70 Fifth Ave., New York Gentlemen:—Enclosed is $2.00 (Canadian $2.00, Foreign $2.50) for 1 year's subscription to the BASEBALL MAGAZINE. -

Ns9uemim a DAY of TIMELY M of SPORT

Refuse Baseball Standing 1 Superbas Still TIMELY m OF SPORT MNTS HAVE M in Three Leagues to Check Pesky Cubs] p-, XATIOSAI i.r %4.t i: oamks to-bat. Colonel Thompson Praises Army Michael O'Suliivan's Fali on ! made only flve hlts, but they took ad- I in. ilinatl at Nrw York. Big Ed Walsh Relieves Lange. but Proves ( ><¦< »«.. at Broofclyn tlwol. Ragon Pitches Fine Ball, j'.antage of their opportunltles. and Navy Men at Stockholm. Thursday Fatal. M, lonia nt PMIailelphia. with the Usual Results. For three tnnlnga lavender held the Ptttsbergb ut Bo-ton. Lavender Wins Honors Bcetrstesa, bat in the. fourth laa* Rl>l l.TS Ol QAMEfl \KSTI.R1I.\Y. Biiaerbaa a two-hngcer hy Wheat was followed Nre York. 4; (inrlnnatl, 0. Ing seor- INSPIRATION TO ATHLETES DICK DONNELLY ALSO HURT Shut Out When of the Battle. an out and Tinker's error, Cincinnati 4*'hl--iig».. *: Broofcltn. 't, DAY bv InftsM <n I'llt-lMireli. 8| Boktoti. u. CHASE HAS A BIG Wh.-at. The Buperbaa tulli'd asaln Fourteen '¦'>¦ to one «d*1e any f.-eling of elvlo lt"g stole Champions Make It -(. laaSBB, ".: Pliiturlrlpbla. -.ling tbe Fixth lnning- Dauhtat .-dngled. aa well aa Cut- Mrs. MIHIN.U. l.i;.t(,l K MANUIM.. prtde and hrotherly feellng. i«ec..nd and »<-ored on a edngle bv McGraw Picks Up Another Fitler'a Pandora and Klng Consecutive Victories. w. i. r.4 tv. i.. P.i'. Steals 4.-. aa .4*»» Rapa Ont Four Hits and refumin? nbnoltitadi to ba of any materlal ahnw. -

Official Game Information

Official Game Information Yankee Stadium • One East 161st Street • Bronx, NY 10451 Media Relations Phone: (718) 579-4460 • [email protected] • Twitter: @yankeespr YANKEES BY THE NUMBERS NOTE 2012 (Postseason) 2012 AMERICAN LEAGUE CHAMPIONSHIP SERIES – GAME 1 Home Record: . 51-30 (2-1) NEW YORK YANKEES (3-2/95-67) vs. DETROIT TIGERS (3-2/88-74) Road Record: . 44-37 (1-1) Day Record: . .. 32-20 (---) LHP ANDY PETTITTE (0-1, 3.86) VS. RHP DOUG FISTER (0-0, 2.57) Night Record: . 63-47 (3-2) Saturday, OctOber 13 • 8:07 p.m. et • tbS • yankee Stadium vs . AL East . 41-31 (3-2) vs . AL Central . 21-16 (---) vs . AL West . 20-15 (---) AT A GLANCE: The Yankees will play Game 1 of the 2012 American League Championship Series vs . the Detroit Tigers tonight at Yankee Stadium…marks the Yankees’ 15th ALCS YANKEES IN THE ALCS vs . National League . 13-5 (---) (Home Games in Bold) vs . RH starters . 58-43 (3-0) all-time, going 11-3 in the series, including a 7-2 mark in their last nine since 1996 – which vs . LH starters . 37-24 (0-2) have been a “best of seven” format…is their third ALCS in five years under Joe Girardi (also YEAR OPP W L Detail Yankees Score First: . 59-27 (2-1) 2009 and ‘10)…are 34-14 in 48 “best-of-seven” series all time . 1976** . KC . 3 . 2 . WLWLW Opp . Score First: . 36-40 (1-1) This series is a rematch of the 2011 ALDS, which the Tigers won in five games . -

Triple Play Tournaments 2016 Triple Play Tournaments Prides Itself in Running Very Organized Tournaments at a Great Value for Youth Baseball Teams

Triple Play Tournaments 2016 Triple Play Tournaments prides itself in running very organized tournaments at a great value for youth baseball teams. All tournaments will be held at local St. Charles County and St. Louis County fields including C&H Ballpark, Woodlands Ballpark, Bridgeton Municipal Athletic Complex (BMAC), and Pacific Athletic Association, other local parks and high school fields may be used for some tournaments. Team Name Age Level Division: A AA AAA Major (Circle One) Head Coach Address Coach’s Email Coach’s Cell Month Dates Ages Divisions Event Ball Park Min Entry Select Games Fee Tournament(s) March 18-20 7u-14u A, AA, AAA Opening Day Classic C & H 4 $375 April 8-10 7u-14u A, AA, AAA Spring Time Classic C & H/ BMAC 3 $375 April 15-17 7u-14u A, AA, AAA Moon Shot Rumble C&H/ STP Sports Complex 3 $375 April 29-5/1 7u-14u A, AA, AAA On the Bump Classic C & H/STP Sports Complex 3 $375 May 13-15 7u-14u A, AA, AAA Swing for the Fences Battle C & H/STP Sports Complex 3 $375 May 14 -15 7u-14u A/Rec Only Spring Fling Pacific 3 $375 May 20-22 7u-18u A, AA, AAA Hot Corner Classic C & H/ BMAC 3 $375 June 3-5 7u-18u A, AA, AAA School’s Out Classic C & H/ TBD 3 $375 June 4-5 7u-18u AA Only June Showdown Pacific 3 $375 June 10-12 7u-18u A, AA, AAA Wood Bat Battle C & H/TBD 3 $375 June 17-19 7u-18u A, AA, AAA Father’s Day Classic C & H/TBD 3 $375 June 24-26 7u-18u A, AA, AAA RBI Bonanza C & H/TBD 3 $375 July 8-10 7u-18u A, AA, AAA July Showdown C & H/Woodlands 3 $375 July 15-17 7u-18u A,AA,AAA Triple Play World Series C&H/ Woodlands -

Yogi Berra Trivia

YOGI BERRA TRIVIA • What city was Yogi Berra born? a ) San Luis Obispo, CA b) St. Lawrence, NY c) St. Louis, MO d) St. Petersburg, FL • Who was Yogi’s best friend growing up? a) Joe Torre b) Joe Garagiola c) Joe Pepitone d) Shoeless Joe Jackson • Who was one of Yogi’s first Yankee roommates and later became a doctor? a) Doc Medich b) Jerry (“Oh, Doctor”) Coleman c) Doc Cramer d) Bobby Brown • When Yogi appeared in the soap opera General Hospital in 1962, who did he play? a) Brain surgeon Dr. Lawrence P. Berra b) Cardiologist Dr. Pepper c) General physician Dr. Yogi Berra d) Dr. Kildare’s cousin • The cartoon character Yogi Bear was created in 1958 and largely inspired by Yogi Berra. a) True, their names and genial personalities can’t be a coincidence. b) False, the creators Hanna-Barbera somehow never heard of Yogi Berra. c) Hanna-Barbera denied that umpire Augie Donatelli inspired the character Augie Doggie. d) Hanna-Barbera seriously considered a cartoon character named Bear Bryant. • In Yogi’s first season (1947), his salary was $5,000. What did he earn for winning the World Series that year? a) A swell lunch with the owners. b) $5,000 winner’s share. c) A trip to the future home of Disney World. d) A gold watch from one of the team sponsors • When Yogi won his first Most Valuable Player Award in 1951, what did he do in the offseason? a) Took a two-month cruise around the world. b) Opened a chain of America’s first frozen yogurt stores. -

Guide to Softball Rules and Basics

Guide to Softball Rules and Basics History Softball was created by George Hancock in Chicago in 1887. The game originated as an indoor variation of baseball and was eventually converted to an outdoor game. The popularity of softball has grown considerably, both at the recreational and competitive levels. In fact, not only is women’s fast pitch softball a popular high school and college sport, it was recognized as an Olympic sport in 1996. Object of the Game To score more runs than the opposing team. The team with the most runs at the end of the game wins. Offense & Defense The primary objective of the offense is to score runs and avoid outs. The primary objective of the defense is to prevent runs and create outs. Offensive strategy A run is scored every time a base runner touches all four bases, in the sequence of 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and home. To score a run, a batter must hit the ball into play and then run to circle the bases, counterclockwise. On offense, each time a player is at-bat, she attempts to get on base via hit or walk. A hit occurs when she hits the ball into the field of play and reaches 1st base before the defense throws the ball to the base, or gets an extra base (2nd, 3rd, or home) before being tagged out. A walk occurs when the pitcher throws four balls. It is rare that a hitter can round all the bases during her own at-bat; therefore, her strategy is often to get “on base” and advance during the next at-bat. -

Triple Plays Analysis

A Second Look At The Triple Plays By Chuck Rosciam This analysis updates my original paper published on SABR.org and Retrosheet.org and my Triple Plays sub-website at SABR. The origin of the extensive triple play database1 from which this analysis stems is the SABR Triple Play Project co-chaired by myself and Frank Hamilton with the assistance of dozens of SABR researchers2. Using the original triple play database and updating/validating each play, I used event files and box scores from Retrosheet3 to build a current database containing all of the recorded plays in which three outs were made (1876-2019). In this updated data set 719 triple plays (TP) were identified. [See complete list/table elsewhere on Retrosheet.org under FEATURES and then under NOTEWORTHY EVENTS]. The 719 triple plays covered one-hundred-forty-four seasons. 1890 was the Year of the Triple Play that saw nineteen of them turned. There were none in 1961 and in 1974. On average the number of TP’s is 4.9 per year. The number of TP’s each year were: Total Triple Plays Each Year (all Leagues) Ye a r T P's Ye a r T P's Ye a r T P's Ye a r T P's Ye a r T P's Ye a r T P's <1876 1900 1 1925 7 1950 5 1975 1 2000 5 1876 3 1901 8 1926 9 1951 4 1976 3 2001 2 1877 3 1902 6 1927 9 1952 3 1977 6 2002 6 1878 2 1903 7 1928 2 1953 5 1978 6 2003 2 1879 2 1904 1 1929 11 1954 5 1979 11 2004 3 1880 4 1905 8 1930 7 1955 7 1980 5 2005 1 1881 3 1906 4 1931 8 1956 2 1981 5 2006 5 1882 10 1907 3 1932 3 1957 4 1982 4 2007 4 1883 2 1908 7 1933 2 1958 4 1983 5 2008 2 1884 10 1909 4 1934 5 1959 2 -

Baseball/Softball

SAMPLE SITUTATIONS Situation Enter for batter Enter for runner Hit (single, double, triple, home run) 1B or 2B or 3B or HR Hit to location (LF, CF, etc.) 3B 9 or 2B RC or 1B 6 Bunt single 1B BU Walk, intentional walk or hit by pitch BB or IBB or HP Ground out or unassisted ground out 63 or 43 or 3UA Fly out, pop out, line out 9 or F9 or P4 or L6 Pop out (bunt) P4 BU Line out with assist to another player L6 A1 Foul out FF9 or PF2 Foul out (bunt) FF2 BU or PF2 BU Strikeouts (swinging or looking) KS or KL Strikeout, Fouled bunt attempt on third strike K BU Reaching on an error E5 Fielder’s choice FC 4 46 Double play 643 GDP X Double play (on strikeout) KS/L 24 DP X Double play (batter reaches 1B on FC) FC 554 GDP X Double play (on lineout) L63 DP X Triple play 543 TP X (for two runners) Sacrifi ce fl y F9 SF RBI + Sacrifi ce bunt 53 SAC BU + Sacrifi ce bunt (error on otherwise successful attempt) E2T SAC BU + Sacrifi ce bunt (no error, lead runner beats throw to base) FC 5 SAC BU + Sacrifi ce bunt (lead runner out attempting addtional base) FC 5 SAC BU + 35 Fielder’s choice bunt (one on, lead runner out) FC 5 BU (no sacrifi ce) 56 Fielder’s choice bunt (two on, lead runner out) FC 5 BU (no sacrifi ce) 5U (for lead runner), + (other runner) Catcher or batter interference CI or BI Runner interference (hit by batted ball) 1B 4U INT (awarded to closest fi elder)* Dropped foul ball E9 DF Muff ed throw from SS by 1B E3 A6 Batter advances on throw (runner out at home) 1B + T + 72 Stolen base SB Stolen base and advance on error SB E2 Caught stealing