Create.Canterbury.Ac.Uk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High School Leaflet

Equipment HIRE: £60 per term OR £150 per year for a set of two posts. KORFBALL (suitable for 16 children to play at the same time). OR £250 for 2 sets per year. £100 for one term. IN YOUR (suitable for a whole class of 32 children on two courts) BUY BACK SCHEME: HIGH CHOOL S If you take part in this Club School Link, Harrow Korfball will reduce the cost of purchase from £780 to £580 per set of posts. AND If you no longer want them, we will buy back the posts in the first year at 100% (£580). This reduces to 60% in year 2. The posts come with a 10 year warrantee. All prices include deliv- ery. KORFBALLS (size 4 or 5) cost £29 per ball when ordered at the same time through Harrow Korfball. We suggest ordering a mini- mum of 4. There is no buy back on balls. Also available is a ‘Teaching Children Korfball’ Manual at £25 which includes 10 lesson plans. The aim We are looking for schools to introduce this fantastic international sport and establish a long term link with your local club. We will give you as much support as possible and look forward to working with you for a new generation of athletes from our boroughs. We will invite you to tournaments and help set up a community club if you want. We have the opportunity to set this generation on the path to representing GB at the 2028 Olympics. Email: [email protected] www.harrowkorfball.com WHAT IS KORFBALL? WHAT WE CAN DO FOR YOU Korfball is the only team sport designed to be mixed, Create a link with Harrow Korfball, a Change4Life sport and it works. -

2017 Anti-Doping Testing Figures Report

2017 Anti‐Doping Testing Figures Please click on the sub‐report title to access it directly. To print, please insert the pages indicated below. Executive Summary – pp. 2‐9 (7 pages) Laboratory Report – pp. 10‐36 (26 pages) Sport Report – pp. 37‐158 (121 pages) Testing Authority Report – pp. 159‐298 (139 pages) ABP Report‐Blood Analysis – pp. 299‐336 (37 pages) ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2017 Anti‐Doping Testing Figures Executive Summary ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2017 Anti-Doping Testing Figures Samples Analyzed and Reported by Accredited Laboratories in ADAMS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Executive Summary is intended to assist stakeholders in navigating the data outlined within the 2017 Anti -Doping Testing Figures Report (2017 Report) and to highlight overall trends. The 2017 Report summarizes the results of all the samples WADA-accredited laboratories analyzed and reported into WADA’s Anti-Doping Administration and Management System (ADAMS) in 2017. This is the third set of global testing results since the revised World Anti-Doping Code (Code) came into effect in January 2015. The 2017 Report – which includes this Executive Summary and sub-reports by Laboratory , Sport, Testing Authority (TA) and Athlete Biological Passport (ABP) Blood Analysis – includes in- and out-of-competition urine samples; blood and ABP blood data; and, the resulting Adverse Analytical Findings (AAFs) and Atypical Findings (ATFs). REPORT HIGHLIGHTS • A analyzed: 300,565 in 2016 to 322,050 in 2017. 7.1 % increase in the overall number of samples • A de crease in the number of AAFs: 1.60% in 2016 (4,822 AAFs from 300,565 samples) to 1.43% in 2017 (4,596 AAFs from 322,050 samples). -

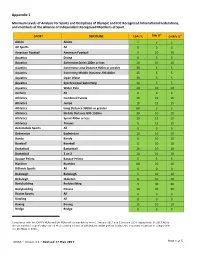

TDSSA Appendix 1

Appendix 1 Minimum Levels of Analysis for Sports and Disciplines of Olympic and IOC Recognized International Federations, and members of the Alliance of Independent Recognized Members of Sport 4 4 SPORT DISCIPLINE ESAs % GHs % GHRFs % Aikido Aikido 5 5 5 Air Sports All 0 0 0 American Football American Football 5 10 10 Aquatics Diving 0 5 5 Aquatics Swimming Sprint 100m or less 10 10 10 Aquatics Swimming Long Distance 800m or greater 30 5 5 Aquatics Swimming Middle Distance 200‐400m 15 5 5 Aquatics Open Water 30 5 5 Aquatics Synchronized Swimming 10 5 5 Aquatics Water Polo 10 10 10 Archery All 0 0 0 Athletics Combined Events 15 15 15 Athletics Jumps 10 15 15 Athletics Long Distance 3000m or greater 60 5 5 Athletics Middle Distance 800‐1500m 30 10 10 Athletics Sprint 400m or less 10 15 15 Athletics Throws 5 15 15 Automobile Sports All 5 0 0 Badminton Badminton 10 10 10 Bandy Bandy 5 10 10 Baseball Baseball 5 10 10 Basketball Basketball 10 10 10 Basketball 3 on 3 10 10 10 Basque Pelota Basque Pelota 5 5 5 Biathlon Biathlon 60 10 10 Billiards Sports All 0 0 0 Bobsleigh Bobsleigh 5 10 10 Bobsleigh Skeleton 0 10 10 Bodybuilding Bodybuilding 5 30 30 Bodybuilding Fitness 10 30 30 Boules Sports All 0 0 0 Bowling All 0 0 0 Boxing Boxing 15 10 10 Bridge Bridge 0 0 0 4 Compliance with the GHRFs MLAs and GH MLAs will be mandatory from 1 January 2017 and 1 January 2018 respectively. -

Sporting Activities and Governing Bodies Recognised by the Sports Councils

MASTER LIST – updated January 2016 Sporting Activities and Governing Bodies Recognised by the Sports Councils Notes: 1. Sporting activities with integrated disability in red 2. Sporting activities with no governing body in blue ACTIVITY DISCIPLINES NORTHERN IRELAND SCOTLAND ENGLAND WALES UK/GB AIKIDO Northern Ireland Aikido Association British Aikido Board British Aikido Board British Aikido Board British Aikido Board AIR SPORTS Flying Ulster Flying Club Royal Aero Club of the UK Royal Aero Club of the UK Royal Aero Club of the UK Royal Aero Club of the UK Aerobatic flying British Aerobatic Association British Aerobatic Association British Aerobatic Association British Aerobatic Association British Aerobatic Association Royal Aero Club of UK Aero model Flying NI Association of Aeromodellers Scottish Aeromodelling Association British Model Flying Association British Model Flying Association British Model Flying Association Ballooning British Balloon and Airship Club British Balloon and Airship Club British Balloon and Airship Club British Balloon and Airship Club Gliding Ulster Gliding Club British Gliding Association British Gliding Association British Gliding Association British Gliding Association Hang/ Ulster Hang Gliding and Paragliding Club Scottish Hang Gliding and Paragliding British Hang Gliding and Paragliding British Hang Gliding and Paragliding British Hang Gliding and Paragliding Paragliding Association Association Association Association Microlight British Microlight Aircraft Association British Microlight Aircraft Association -

List of Acronyms in the Anti-Doping Movement

ADOKICKSTART LIST OF ACRONYMS IN THE ANTI-DOPING MOVEMENT LIST OF ACRONYMS IN THE ANTI-DOPING MOVEMENT A AAF Adverse Analytical Finding ABCD Brazilian Anti-Doping Agency ABP Athlete Biological Passport ABPS Abnormal Blood Profile Score (ABPS) AD Anti-Doping ADAMS Anti-Doping Administration and Management System ADAMAS Anti-Doping Agency of Malaysia ADAS Anti-Doping Agency of Serbia ADD Anti-Doping Denmark ADN Anti-Doping Norway AD Anti-Doping Organisation/Organization ADOP Anti-Doping Authority Portugal ADOP Anti-Doping Organisation of Pakistan ADRs Anti-Doping Rules ADRQ Anti-Doping Results Questionnaire ADRV Anti-Doping Rules Violation AEA Spanish National Anti-Doping Agency AEP Athlete Endocrinological Passport AFLD French Agency for the Fight Against Doping AGM Annual General Meeting AHP Athlete Hematological Passport AIBA International Boxing Association AIMS Alliance of Independent Recognised Members of Sport AIOWF Association of International Olympic Winter Sports Federations ALAD Luxembourg Agency for the Fight Against Doping APF Adverse Passport Finding APMU Athlete Passport Management Unit ARISF Association of IOC Recognized International Sports Federations ASADA Australian Sports Anti-Doping Authority ASOIF Association of Summer Olympic International Federations 01 January 2019 1 Version 5.0 ADOKICKSTART LIST OF ACRONYMS IN THE ANTI-DOPING MOVEMENT ASP Athlete Steroidal Passport ATF Atypical Finding ATPF Atypical Passport Finding APF Adverse Passport Finding AZADA Azerbaijan Anti-Doping Organisation B BADC Bahamas Anti-Doping -

Sports Newsletter

APEC Sports Newsletter 04 March 2018 ISSUE Digital Economy X Esports Foreword / 02 APEC Economies' Policies / 03 -Overview of Current Esports Policies in Different Economies / 03 -Introduction of the Development of esports in the Republic of Korea; Malaysia; and the Netherlands / 06 Perspectives on Regional Sports Issues / 21 -Anticipation and Excitement at the 2018 Taipei Game Show / 21 -The 2018 IeSF ESports World Championship Will Take Place in Kaohsiung / 25 -Countdown to Jakarta Palembang 2018 – the 18th Asian Games / 29 -Korfball aims for the 2023 Southeast Asian Games in Cambodia / 32 -An Assembly of Olympians - The Establishment of the Chinese Taipei Olympians Association / 34 ASPN Related Events / 36 APEC Economies' Perspectives on ASPN Related Foreword Policies Regional Sports Issues Events Foreword APEC's theme for 2018 is "Harnessing Inclusive Opportunities, Embracing the Digital Future." The digital economy is an essential aspect of APEC's trade and investment facilitation action plans to promote the growth of interregional productivity, foster innovation and structural reforms, encourage the economic participation of small and medium enterprises (SME) and vulnerable groups, and support human resources development in the region. The rise of the digital economy has had a tremendous impact on all walks of life. It is a key force driving global economic development and has transformed economic and social activities and work behaviors of individuals and entire societies. Thus, the various member economies of APEC must guide and assist their citizens in preparing for this changing work environment and developing the skills necessary to meet the needs of the digital market. In recent years, the esports trend has swept the world to become a digital industry with great economic potential. -

Jonathan Porter, 2021 World Games February 17 Program: Jody Hunt, Asst. US Attorney General

February 10, 2020 PO Box 530342, Birmingham, 35223 shadesvalleyrotary.org Volume 55 Issue 28 Today’s Program: Jonathan Porter, 2021 World Games Jonathan Porter is senior vice president responsible for Customer Operations for Alabama Power-Jonathan is also the Chairman of the 2021 World Games. In his position at Alabama Power Jonathan provides strategic leadership over customer operations, including the company’s business offices, the Customer Service Center, Business Service Center and Online Customer Care. He joined Alabama Power in 2000 and has held various roles of increasing responsibility in the company’s Human Resources and Customer Services organizations. Porter is chairman of the 2021 Birmingham World Games Foundation and serves as a board trustee for his alma mater, Tuskegee University. He serves as a member of the board of directors for the Jefferson County Education Foundation, United Way of Central Alabama, Birmingham Business Alliance, Birmingham Civil Rights Institute and A.G. Gaston Boys & Girls Club, among numerous other community and civic organizations. He is a member of the Newcomen Society of Alabama. Porter holds a bachelor’s degree in business administration from Tuskegee University. He received a Master of Business Administration from the University of Alabama at Birmingham. The World Games 2021 - Birmingham The purpose of The World Games is to conduct multi-sport events for sports and disciplines that are not contested in the Olympic Games. The World Games is an extraordinary, international sports event held every -

THE RULES of KORFBALL Field of Play and Bench - Field

THE RULES OF KORFBALL Field of play and bench - Field. Divided into two equal zones. The ratio of length to width is 2:1. Marking - Rectangular court with a clearly marked centre line. The penalty spots must be marked at a distance of 2.50 m in front of the posts as seen from the centre of the eld. Posts - Posts are erected in both zones at a point-situate d midway between the two sidelines and one-sixth of the length of the eld of play from the end line. Baskets - A cylindrical bottomless basket is tted to each post. The basket must face towards the centre and all of its top edge must be 3.50 m above the ground. Ball - Korfball is played with a round ball (we would recommend a Netball). Circumference will be approximately 68.8-70.5cm. Players - Number and position. Each team consists of four male and four female players, of whom two male and two female players are placed in each zone. - Incomplete teams. When one or both teams are incomp lete, the game can only st art or be continued if a line-up is possible which ensures that no zone has le ss than three players from ea ch side and that in no zone one female and two male players are opposed by one male and two female players. - Substitution of players. Up to two players of a team can be substituted. After these substitutions have been made, injured players who can no longer take part in the match may be substituted with the permission of the referee. -

Administration's Paper on Promotion of Sports Development in Hong Kong

LC Paper No. CB(2)1500/18-19(05) For discussion on 27 May 2019 Legislative Council Panel on Home Affairs Promotion of Sports Development in Hong Kong Purpose This paper reports to Members on the latest situation of the Government’s work in promoting sports development in Hong Kong. Background 2. The Government has been supporting the development of sports in Hong Kong and is committed to promoting sports in the community, supporting elite sports and developing Hong Kong into a centre for major international sports events. The Sports Commission (SC) and its three committees (namely the Community Sports Committee, Elite Sports Committee and Major Sports Events Committee (MSEC)), established by the HAB, provide advice on sports policies and related measures. The HAB and the Leisure and Cultural Services Department (LCSD) maintain close liaison with the sports sector, including the Sports Federation & Olympic Committee of Hong Kong, China (SF&OC), the Hong Kong Sports Institute (HKSI), “national sports associations” (NSAs) and related sports organisations, coaches and athletes, to understand their views on sports development in Hong Kong. 3. To promote sports development, the Government has since 2017 invested over $60 billion of new resources, including $31.9 billion for the development of the Kai Tak Sports Park (the Sports Park) project, around $20 billion for the construction of recreational and sports facilities in the 18 districts and around $8 billion for the sustainable development of elite and community sports1. In addition, the -

List of Sports

List of sports The following is a list of sports/games, divided by cat- egory. There are many more sports to be added. This system has a disadvantage because some sports may fit in more than one category. According to the World Sports Encyclopedia (2003) there are 8,000 indigenous sports and sporting games.[1] 1 Physical sports 1.1 Air sports Wingsuit flying • Parachuting • Banzai skydiving • BASE jumping • Skydiving Lima Lima aerobatics team performing over Louisville. • Skysurfing Main article: Air sports • Wingsuit flying • Paragliding • Aerobatics • Powered paragliding • Air racing • Paramotoring • Ballooning • Ultralight aviation • Cluster ballooning • Hopper ballooning 1.2 Archery Main article: Archery • Gliding • Marching band • Field archery • Hang gliding • Flight archery • Powered hang glider • Gungdo • Human powered aircraft • Indoor archery • Model aircraft • Kyūdō 1 2 1 PHYSICAL SPORTS • Sipa • Throwball • Volleyball • Beach volleyball • Water Volleyball • Paralympic volleyball • Wallyball • Tennis Members of the Gotemba Kyūdō Association demonstrate Kyūdō. 1.4 Basketball family • Popinjay • Target archery 1.3 Ball over net games An international match of Volleyball. Basketball player Dwight Howard making a slam dunk at 2008 • Ball badminton Summer Olympic Games • Biribol • Basketball • Goalroball • Beach basketball • Bossaball • Deaf basketball • Fistball • 3x3 • Footbag net • Streetball • • Football tennis Water basketball • Wheelchair basketball • Footvolley • Korfball • Hooverball • Netball • Peteca • Fastnet • Pickleball -

World, Continental and Intercontinental Games

Historical Archives Olympic Studies Centre World, Continental and Intercontinental Games Fonds sheet Overview of Archives content linked to the preparation, organisation and holding of these Games between 1924 and 1989 29 November 2012 © 2012 / International Olympic Committee (IOC) Fonds sheet Summary Summary ...................................................................................................................... 1 World Games ............................................................................................................... 2 All-Africa Games .......................................................................................................... 4 Pan-American Games ................................................................................................. 7 Asian Games .............................................................................................................. 10 European Games ....................................................................................................... 12 Afro-Asian Games ..................................................................................................... 15 Last update: Nov. 2012 World, Continental and Intercontinental Games Historical Archives / Olympic Studies Centre / [email protected] p 1/16 Fonds sheet World Games Reference: CH IOC-AH H-FC01-IWGA Dates: 1975-1988 Level of description: sub-series Extent and medium: 0.08 lm. Text documents. Name of creator International Olympic Committee (IOC). Administrative history/ Biographical -

IOC Recognized Sports – the Next Olympic Generation

The International World of Sports and the IFF Dr Jan C. Fransoo President, Association of IOC Recognized International Sports Federations (ARISF) President, International Korfball Federation (IKF) Council Member, SportAccord / GAISF Today’s Agenda Recognized Sports and ARISF World Games and Olympic Games program SportAccord services Discussion www.arisf.org 2 IOC Recognized Sports Are recognized by the IOC Are not yet on the Olympic Program Represent the interests of the youth of the world Are the vehicle to develop the Olympic Program www.arisf.org 3 Olympic Movement IOC International National Olympic Federations Committees www.arisf.org 4 Composition of the IOC 70 individual membersIOC15 NOC representatives 15 IF repesentatives 15 Athletes International National Olympic Federations Committees www.arisf.org 5 International Federations IOC Olympic Games IFs Olympic Games IFs (Summer) National(Winter) Olympic Committees Recognized IFs (Not on program) www.arisf.org 6 Associations of International Federations IOC ASOIF AOIWF (Summer) National(Winter) Olympic Committees ARISF (Not on program) www.arisf.org 7 Associations of International Federations IOC ASOIF AOIWF (Summer) National(Winter) Olympic Committees ARISF (Not on program) SportAccord / GAISF others others (Non-IOC-recognized)www.arisf.org (Non-GAISF-recognized)8 ARISF Association of IOC Recognized International Sports Federations Established in 1984 30-34 members www.arisf.org 9 Olympic Charter In order to develop and promote the Olympic Movement, the IOC may recognise as International Federations international non- governmental organisations administering one or several sports at world level and encompassing organisations administering such sports at national level (Art. 26) The IOC may recognize [..] associations of International Federations (Art.