P0876-P0879.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

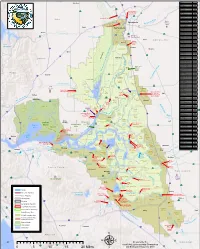

0 5 10 15 20 Miles Μ and Statewide Resources Office

Woodland RD Name RD Number Atlas Tract 2126 5 !"#$ Bacon Island 2028 !"#$80 Bethel Island BIMID Bishop Tract 2042 16 ·|}þ Bixler Tract 2121 Lovdal Boggs Tract 0404 ·|}þ113 District Sacramento River at I Street Bridge Bouldin Island 0756 80 Gaging Station )*+,- Brack Tract 2033 Bradford Island 2059 ·|}þ160 Brannan-Andrus BALMD Lovdal 50 Byron Tract 0800 Sacramento Weir District ¤£ r Cache Haas Area 2098 Y o l o ive Canal Ranch 2086 R Mather Can-Can/Greenhead 2139 Sacramento ican mer Air Force Chadbourne 2034 A Base Coney Island 2117 Port of Dead Horse Island 2111 Sacramento ¤£50 Davis !"#$80 Denverton Slough 2134 West Sacramento Drexler Tract Drexler Dutch Slough 2137 West Egbert Tract 0536 Winters Sacramento Ehrheardt Club 0813 Putah Creek ·|}þ160 ·|}þ16 Empire Tract 2029 ·|}þ84 Fabian Tract 0773 Sacramento Fay Island 2113 ·|}þ128 South Fork Putah Creek Executive Airport Frost Lake 2129 haven s Lake Green d n Glanville 1002 a l r Florin e h Glide District 0765 t S a c r a m e n t o e N Glide EBMUD Grand Island 0003 District Pocket Freeport Grizzly West 2136 Lake Intake Hastings Tract 2060 l Holland Tract 2025 Berryessa e n Holt Station 2116 n Freeport 505 h Honker Bay 2130 %&'( a g strict Elk Grove u Lisbon Di Hotchkiss Tract 0799 h lo S C Jersey Island 0830 Babe l Dixon p s i Kasson District 2085 s h a King Island 2044 S p Libby Mcneil 0369 y r !"#$5 ·|}þ99 B e !"#$80 t Liberty Island 2093 o l a Lisbon District 0307 o Clarksburg Y W l a Little Egbert Tract 2084 S o l a n o n p a r C Little Holland Tract 2120 e in e a e M Little Mandeville -

Transitions for the Delta Economy

Transitions for the Delta Economy January 2012 Josué Medellín-Azuara, Ellen Hanak, Richard Howitt, and Jay Lund with research support from Molly Ferrell, Katherine Kramer, Michelle Lent, Davin Reed, and Elizabeth Stryjewski Supported with funding from the Watershed Sciences Center, University of California, Davis Summary The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta consists of some 737,000 acres of low-lying lands and channels at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers (Figure S1). This region lies at the very heart of California’s water policy debates, transporting vast flows of water from northern and eastern California to farming and population centers in the western and southern parts of the state. This critical water supply system is threatened by the likelihood that a large earthquake or other natural disaster could inflict catastrophic damage on its fragile levees, sending salt water toward the pumps at its southern edge. In another area of concern, water exports are currently under restriction while regulators and the courts seek to improve conditions for imperiled native fish. Leading policy proposals to address these issues include improvements in land and water management to benefit native species, and the development of a “dual conveyance” system for water exports, in which a new seismically resistant canal or tunnel would convey a portion of water supplies under or around the Delta instead of through the Delta’s channels. This focus on the Delta has caused considerable concern within the Delta itself, where residents and local governments have worried that changes in water supply and environmental management could harm the region’s economy and residents. -

Programmatic Environmental Impact Report

Water Hyacinth Control Program FINAL Programmatic Environmental Impact Report Volume I – Chapters 1 to 7 November 30, 2009 A program for effective control of Water Hyacinth in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and its tributaries. Copies of this Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Report in hard copy form, or on computer compact disc (CD), can be obtained from the California Department of Boating and Waterways. To request a report copy, please contact: Ms. Terri Ely Aquatic Weed Program California Department of Boating and Waterways 2000 Evergreen Street, Suite 100 Sacramento, California 95815 (916) 263-8138 [email protected] Cover photo: March 14, 2008, by NewPoint Group, Inc., of the Wheeler Island Duck Club, at Honker Bay. [PARTIAL] Water Hyacinth Control Program Water Hyacinth Control Program A program for effective control of Water Hyacinth in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and its tributaries. FINAL Programmatic Environmental Impact Report Volume I – Chapters 1 to 7 November 30, 2009 Prepared by: The California Department of Boating and Waterways With Technical Assistance from: NewPoint Group, Inc. 2555 Third Street, Suite 215 Sacramento, California 95818 (916) 442-0508 www.newpointgroup.com ~----Pei:at f~m.A; _ _,__,..._... AniJru--~- ' --sepat Table of Contents Volume I – Chapters 1 to 7 Page Acronyms and Abbreviations ......................................................... AA-1 Executive Summary.......................................................................... ES-1 1. Introduction ........................................................................................ -

GRA 9 – South Delta

2-900 .! 2-905 .! 2-950 .! 2-952 2-908 .! .! 2-910 .! 2-960 .! 2-915 .! 2-963 .! 2-964 2-965 .! .! 2-917 .! 2-970 2-920 ! .! . 2-922 .! 2-924 .! 2-974 .! San Joaquin County 2-980 2-929 .! .! 2-927 .! .! 2-925 2-932 2-940 Contra Costa .! .! County .! 2-930 2-935 .! Alameda 2-934 County ! . Sources: Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, USGS, Intermap, iPC, NRCAN, Esri Japan, METI, Esri China (Hong Kong), Esri (Thailand), TomTom, 2013 Calif. Dept. of Fish and Wildlife Area Map Office of Spill Prevention and Response I Data Source: O SPR NAD_1983_C alifornia_Teale_Albers ACP2 - GRA9 Requestor: ACP Coordinator Author: J. Muskat Date Created: 5/2 Environmental Sensitive Sites Section 9849 – GRA 9 South Delta Table of Contents GRA 9 Map ............................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................... 2 Site Index/Response Action ...................................................................................................... 3 Summary of Response Resources for GRA 9......................................................................... 4 9849.1 Environmentally Sensitive Sites 2-900-A Old River Mouth at San Joaquin River....................................................... 1 2-905-A Franks Tract Complex................................................................................... 4 2-908-A Sand Mound Slough .................................................................................. -

Transitions for the Delta Economy

Transitions for the Delta Economy January 2012 Josué Medellín-Azuara, Ellen Hanak, Richard Howitt, and Jay Lund with research support from Molly Ferrell, Katherine Kramer, Michelle Lent, Davin Reed, and Elizabeth Stryjewski Supported with funding from the Watershed Sciences Center, University of California, Davis Summary The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta consists of some 737,000 acres of low-lying lands and channels at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers (Figure S1). This region lies at the very heart of California’s water policy debates, transporting vast flows of water from northern and eastern California to farming and population centers in the western and southern parts of the state. This critical water supply system is threatened by the likelihood that a large earthquake or other natural disaster could inflict catastrophic damage on its fragile levees, sending salt water toward the pumps at its southern edge. In another area of concern, water exports are currently under restriction while regulators and the courts seek to improve conditions for imperiled native fish. Leading policy proposals to address these issues include improvements in land and water management to benefit native species, and the development of a “dual conveyance” system for water exports, in which a new seismically resistant canal or tunnel would convey a portion of water supplies under or around the Delta instead of through the Delta’s channels. This focus on the Delta has caused considerable concern within the Delta itself, where residents and local governments have worried that changes in water supply and environmental management could harm the region’s economy and residents. -

Comparing Futures for the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta

comparing futures for the sacramento–san joaquin delta jay lund | ellen hanak | william fleenor william bennett | richard howitt jeffrey mount | peter moyle 2008 Public Policy Institute of California Supported with funding from Stephen D. Bechtel Jr. and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation ISBN: 978-1-58213-130-6 Copyright © 2008 by Public Policy Institute of California All rights reserved San Francisco, CA Short sections of text, not to exceed three paragraphs, may be quoted without written permission provided that full attribution is given to the source and the above copyright notice is included. PPIC does not take or support positions on any ballot measure or on any local, state, or federal legislation, nor does it endorse, support, or oppose any political parties or candidates for public office. Research publications reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, officers, or Board of Directors of the Public Policy Institute of California. Summary “Once a landscape has been established, its origins are repressed from memory. It takes on the appearance of an ‘object’ which has been there, outside us, from the start.” Karatani Kojin (1993), Origins of Japanese Literature The Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta is the hub of California’s water supply system and the home of numerous native fish species, five of which already are listed as threatened or endangered. The recent rapid decline of populations of many of these fish species has been followed by court rulings restricting water exports from the Delta, focusing public and political attention on one of California’s most important and iconic water controversies. -

UC Davis San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science

UC Davis San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science Title Implications for Greenhouse Gas Emission Reductions and Economics of a Changing Agricultural Mosaic in the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/99z2z7hb Journal San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science, 15(3) ISSN 1546-2366 Authors Deverel, Steven Jacobs, Paul Lucero, Christina et al. Publication Date 2017 DOI 10.15447/sfews.2017v15iss3art2 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California SEPTEMBER 2017 RESEARCH Implications for Greenhouse Gas Emission Reductions and Economics of a Changing Agricultural Mosaic in the Sacramento – San Joaquin Delta Steven Deverel1, Paul Jacobs2, Christina Lucero1, Sabina Dore1, and T. Rodd Kelsey3 profit changes relative to the status quo. We spatially Volume 15, Issue 3 | Article 2 https://doi.org/10.15447/sfews.2017v15iss3art2 assigned areas for rice and wetlands, and then allowed the Delta Agricultural Production (DAP) * Corresponding author: [email protected] model to optimize the allocation of other crops to 1 HydroFocus, Inc. maximize profit. The scenario that included wetlands 2827 Spafford Street, Davis, CA 95618 USA decreased profits 79% relative to the status quo but 2 University of California, Davis -1 One Shields Ave, Davis, CA 95616 USA reduced GHG emissions by 43,000 t CO2-e yr (57% 3 The Nature Conservancy reduction). When mixtures of rice and wetlands were 555 Capitol Mall Suite 1290, Sacramento, CA 95814 USA introduced, farm profits decreased 16%, and the GHG -1 emission reduction was 33,000 t CO2-e yr (44% reduction). -

Workshop Report—Earthquakes and High Water As Levee Hazards in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta

Workshop report—Earthquakes and High Water as Levee Hazards in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Delta Independent Science Board September 30, 2016 Summary ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Workshop ........................................................................................................................................ 1 Scope ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Structure ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Participants and affiliations ........................................................................................................ 2 Highlights .................................................................................................................................... 3 Earthquakes ............................................................................................................................. 3 High water ............................................................................................................................... 4 Perspectives.................................................................................................................................... -

Historic, Recent, and Future Subsidence, Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, California, USA

UC Davis San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science Title Historic, Recent, and Future Subsidence, Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, California, USA Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7xd4x0xw Journal San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science, 8(2) ISSN 1546-2366 Authors Deverel, Steven J Leighton, David A Publication Date 2010 DOI https://doi.org/10.15447/sfews.2010v8iss2art1 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7xd4x0xw#supplemental License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California august 2010 Historic, Recent, and Future Subsidence, Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, California, USA Steven J. Deverel1 and David A. Leighton Hydrofocus, Inc., 2827 Spafford Street, Davis, CA 95618 AbStRACt will range from a few cm to over 1.3 m (4.3 ft). The largest elevation declines will occur in the central To estimate and understand recent subsidence, we col- Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta. From 2007 to 2050, lected elevation and soils data on Bacon and Sherman the most probable estimated increase in volume below islands in 2006 at locations of previous elevation sea level is 346,956,000 million m3 (281,300 ac-ft). measurements. Measured subsidence rates on Sherman Consequences of this continuing subsidence include Island from 1988 to 2006 averaged 1.23 cm year-1 increased drainage loads of water quality constitu- (0.5 in yr-1) and ranged from 0.7 to 1.7 cm year-1 (0.3 ents of concern, seepage onto islands, and decreased to 0.7 in yr-1). Subsidence rates on Bacon Island from arability. -

California Regional Water Quality Control Board Central Valley Region Karl E

California Regional Water Quality Control Board Central Valley Region Karl E. Longley, ScD, P.E., Chair Linda S. Adams Arnold 11020 Sun Center Drive #200, Rancho Cordova, California 95670-6114 Secretary for Phone (916) 464-3291 • FAX (916) 464-4645 Schwarzenegger Environmental http://www.waterboards.ca.gov/centralvalley Governor Protection 18 August 2008 See attached distribution list DELTA REGIONAL MONITORING PROGRAM STAKEHOLDER PANEL KICKOFF MEETING This is an invitation to participate as a stakeholder in the development and implementation of a critical and important project, the Delta Regional Monitoring Program (Delta RMP), being developed jointly by the State and Regional Boards’ Bay-Delta Team. The Delta RMP stakeholder panel kickoff meeting is scheduled for 30 September 2008 and we respectfully request your attendance at the meeting. The meeting will consist of two sessions (see attached draft agenda). During the first session, Water Board staff will provide an overview of the impetus for the Delta RMP and initial planning efforts. The purpose of the first session is to gain management-level stakeholder input and, if possible, endorsement of and commitment to the Delta RMP planning effort. We request that you and your designee attend the first session together. The second session will be a working meeting for the designees to discuss the details of how to proceed with the planning process. A brief discussion of the purpose and background of the project is provided below. In December 2007 and January 2008 the State Water Board, Central Valley Regional Water Board, and San Francisco Bay Regional Water Board (collectively Water Boards) adopted a joint resolution (2007-0079, R5-2007-0161, and R2-2008-0009, respectively) committing the Water Boards to take several actions to protect beneficial uses in the San Francisco Bay/Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Estuary (Bay-Delta). -

Subsidence Reversal for Tidal Reconnection

PERFORMANCE MEASURE 4.12: SUBSIDENCE REVERSAL FOR TIDAL RECONNECTION Performance Measure 4.12: Subsidence Reversal for Tidal Reconnection Performance Measure (PM) Component Attributes Type: Output Performance Measure Description 1 Subsidence reversal 0F activities are located at shallow subtidal elevations to prevent net loss of future opportunities to restore tidal wetlands in the Delta and Suisun Marsh. Expectations Preventing long-term net loss of land at intertidal elevations in the Delta and Suisun Marsh from impacts of sea level rise and land subsidence. Metric 1. Acres of Delta and Suisun Marsh land with subsidence reversal activity located on islands with large areas at shallow subtidal elevations. This metric will be reported annually. 2. Average elevation accretion at each project site presented in centimeters per year. This metric will be reported every five years. Baseline 1. In 2019, zero acres of subsidence reversal on islands with large areas at shallow subtidal elevations. 2. Short-term elevation accretion in the Delta at 4 centimeters per year. 1 Subsidence reversal is a process that halts soil oxidation and accumulates new soil material in order to increase land elevations. Examples of subsidence reversal activities are rice cultivation, managed wetlands, and tidal marsh restoration. DELTA PLAN, AMENDED – PRELIMINARY DRAFT NOVEMBER 2019 1 PERFORMANCE MEASURE 4.12: SUBSIDENCE REVERSAL FOR TIDAL RECONNECTION Target 1. By 2030, 3,500 acres in the Delta and 3,000 acres in Suisun Marsh with subsidence reversal activities on islands, with at least 50 percent of the area or with at least 1,235 acres at shallow subtidal elevations. 2. An average elevation accretion of subsidence reversal is at least 4 centimeters per year up to 2050. -

Initial Study/Mitigated Negative Declaration Bacon Island Levee Rehabilitation Project State Clearinghouse No. 2017012062

FINAL ◦ MAY 2017 Initial Study/Mitigated Negative Declaration Bacon Island Levee Rehabilitation Project State Clearinghouse No. 2017012062 PREPARED FOR PREPARED BY Reclamation District No. 2028 Stillwater Sciences (Bacon Island) 279 Cousteau Place, Suite 400 343 East Main Street, Suite 815 Davis, CA 95618 Stockton, CA 95202 Stillwater Sciences FINAL Initial Study/Mitigated Negative Declaration Bacon Island Levee Rehabilitation Project Suggested citation: Reclamation District No. 2028. 2016. Public Review Draft Initial Study/Mitigated Negative Declaration: Bacon Island Levee Rehabilitation Project. Prepared by Stillwater Sciences, Davis, California for Reclamation District No. 2028 (Bacon Island), Stockton, California. Cover photo: View of Bacon Island’s northwestern levee corner and surrounding interior lands. May 2017 Stillwater Sciences i FINAL Initial Study/Mitigated Negative Declaration Bacon Island Levee Rehabilitation Project PROJECT SUMMARY Project title Bacon Island Levee Rehabilitation Project Reclamation District No. 2028 CEQA lead agency name (Bacon Island) and address 343 East Main Street, Suite 815 Stockton, California 95202 Department of Water Resources (DWR) Andrea Lobato, Manager CEQA responsible agencies The Metropolitan Water District of Southern California (Metropolitan) Deirdre West, Environmental Planning Manager David A. Forkel Chairman, Board of Trustees Reclamation District No. 2028 343 East Main Street, Suite 815 Stockton, California 95202 Cell: (510) 693-9977 Nate Hershey, P.E. Contact person and phone District